Goa's only Sunday Mass in Portuguese

Three questions posed by Goa-based journalist Alexandre Moniz Barbosa and my replies (which he translated into Portuguese) as part of his report titled "Uma missa com uma história que mantém viva uma língua", published in Somos! https://somosportugues.com/2023/08/11/uma-missa-com-uma-historia-que-mantem-viva-uma-lingua/

You've been attending the Portuguese mass for years. For some time it was your family that was keeping it going. How was that experience?

I have been attending Sunday Mass in Portuguese since 1970, when the post-Vatican II Ordinário da Missa was published. As we spoke Portuguese at home, attending Mass in the same language was the most natural thing to do. My dear departed father helped out by allotting the Readings and we as a family were an integral part of the choir. In the 1980s, we witnessed traditional hymns slowly giving way to modern tunes (some of them Brazilian). That hymnal, Cantemos Juntos, is still in use.

Why do you think having a Portuguese mass in Goa is important?

Churches and chapels in Goa discontinued Mass in Portuguese two decades ago, but the capital city’s main church has held fast to tradition. Successive parish priests have happily obliged even though the number of attendees has dwindled over the years. It is also remarkable that even now there are people who feel comfortable attending Mass in Portuguese. When Goa’s tourist season begins, in October, Portuguese-speaking visitors make it a point to fulfil their Sunday obligation at the church of the Immaculate Conception.

How would you motivate youth to come to this Mass?

This Mass has a niche attendance. The labourers are few, so to say, and practical difficulties many. On the other hand, there are easier options available, in English and Konkani. All that has made it somewhat tough to keep the Mass going. However, of late, thanks to the revival of interest in Portuguese, many youngsters learning the language in schools and colleges are happy to come and even sing in the choir alongside the seniors. Recently, a young visitor from Maharashtra told me that he had felt transported to Portugal!

(Pic credits: AMB)

Stuti and the Strings

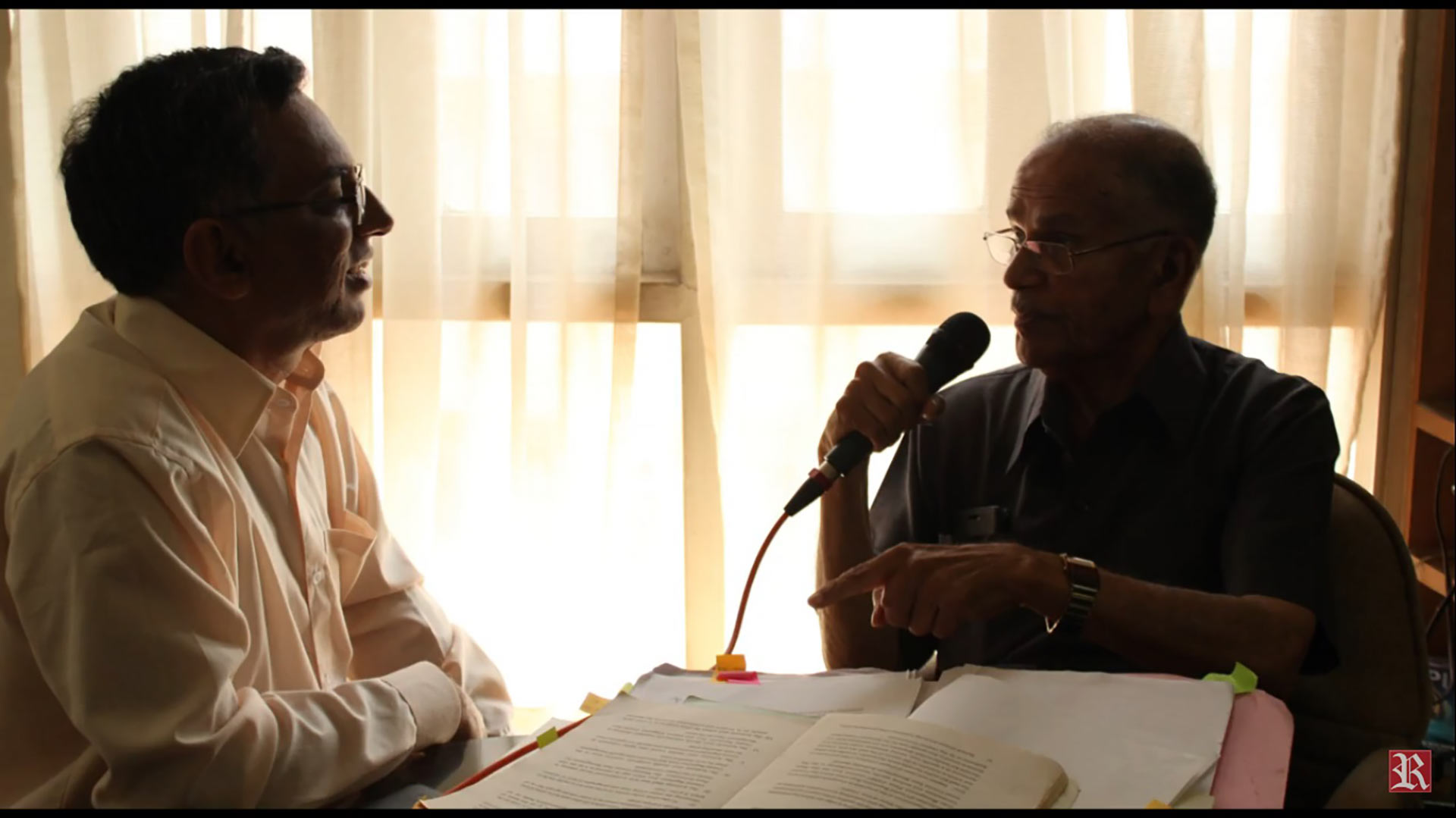

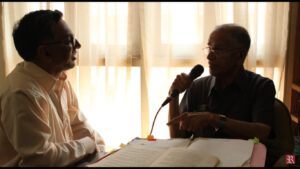

This is a translation of a chat I had with Fr Eufemiano Miranda, founder of Goa String Orchestra and Stuti Chorale Ensemble, on my podcast Renascença Goa. Click here for the original chat in Portuguese.

O.N. Father Miranda, to begin with, tell us something about how these two entities were born, and for what purposes!

E.M. Well, I first started the Goa String Orchestra… that was some time in 2003, when here in Goa we had a choir coming from King’s College, England. They presented a beautiful programme at the church of St Francis of Assisi… And then I thought to myself: we in Goa who always say we are the Italians of the East… we have nothing organized, be it a small orchestra, a small choir… None of that. It was worth having something.

At that time, there were some young people who had graduated in violin, viola, cello. And there were also teachers, among them Myra Shroff, who has taught almost a whole generation of students; and she would always say to me: ‘ah, can’t we have a little string orchestra?’ And I would say, ‘why not?’ So, with whatever we had, I started an orchestra.

Well, it’s not enough just to bring together the members of an orchestra; you have to have a dynamic person behind it, to give it life, to give it movement. And at that time, I started the Goa String Orchestra with Mr Nigel Dixon, who was then with the Kala Academy.

O.N. Very good. That was around 2003. And years later…?

E.M. And later on, there were people who watched our shows and enjoyed what we performed; and there were people who wanted to sing – people with good voices – and with these people I started the Stuti Choral Ensemble, in 2009. It has always been my goal to keep the tradition of classical music alive in Goa…

O.N. Father, you are the driving force behind both these entities…

E.M. Well, I like to use a simpler word: I am a coordinator. My job is to say to these musicians: ‘Come here, let’s make music’; and with their collaboration, I do my work.

O.N. Father, you are much more than that… you have an important voice in both entities, both figuratively and literally speaking, because you also sing!

E.M. Ah, yes! I sing, I enjoy, I enjoy singing. I sing tenor.

O.N. And how many members does Stuti and Goa String Orchestra consist of?

E.M. At Goa Strings, I have a few who, I would say, are regular artists… these would be about 10. Every year there are students who graduate, and I keep calling them; and I like to form a string orchestra with some 18 members or so…

O.N. So, Stuti always has Goa Strings for musical backing…!

E.M. No, no; each entity works independently, but, as you know, in Goa it is difficult to organize concerts in two modalities, choral and instrumental; and so, I prefer to call the choir and orchestra to present a programme together.

O.N. And so far, you must have done at least twenty-five programmes, both inside and outside Goa…!

E.M. That’s it! When Stuti was formed, we immediately got a call from the Bangalore School of Music for a Christmas programme. And it was going to be our first opportunity to perform in public, outside of Goa. We got good reviews in the Bangalore papers. I would say this gave us new motivation.

Well, we always work within our means. For example, at the moment, I am working with a person, a good friend of mine, Antonio Calisto Vaz, and I have asked him to direct the Stuti Choral Ensemble. But I consider it a divine grace that I have conductor Parvesh Java with me.

Fostering Goan Musical Talent

O.N. In the general plan of both Stuti and the Strings Orchestra, what role does the Goan musical repertoire play?

E.M. As I have always said, my ideal is to preserve Goan music. Evidently, we have music from the Christian community of Goa, both religious music and folk music. In my orchestra programme I always wanted to have Goan music played by the orchestra, and we had to present programmes: so, what would we present? My brother, Francisco Miranda, who is a priest and good musician, and I chose “Diptivont Sulakini”: it was so beautiful! I wrote an introduction; he wrote that for two flutes and strings, and accompanied by small Indian timpani (kansaddi), because, as you know, that is a typical Goan music. It’s a Western melody, I would say, but not entirely Western, but not an Eastern melody either, but it’s typically Goan, and one that can be perfectly performed to the Indian rhythm, let’s say. Then I could perfectly play it using the tabla and kansaddi. And we did that under the baton of Nauzer Daruwala. It was really beautiful…

O.N. Well, what adds value to your work, Father, is that you not only perform, but also take the trouble of working on arrangements and harmonies…

E.M. That’s it! We are a group, let’s say, that sings stylized music, in four voices. It is necessary to harmonize that to four voices. If an orchestra is going to play that, it needs to be harmonized for five strings, so the very fact that our group, both instrumental and choral, is a stylized, erudite group, we have to make this music, whether folk or religious, more stylized. After all, what was that music from Europe? Pablo de Sarasate, for example, wrote the Spanish dances: it’s music from Spain that he stylized. The same with Brahms who did the Hungarian dances; Dvorak wrote the Slavonic dances. My way of thinking is this: why can’t we do the same?

O.N. And how do you solve logistical problems?

E.M. I always say to my choir and orchestra members: look, we have to make music for music’s sake, art for art’s sake. Our rehearsal time is 6.30 p.m. to 8.00 p.m. I am very grateful to Kala Academy for giving us the facility to use the rehearsal room once a week…every Wednesday.

O.N. So, what plans for the near future?

E.M. I don’t have big plans. We want to continue to do the work that we are doing, that is, to value music from Goa and to have a group here that is a voice that represents Goa, and in the event of having to present a programme, we would be ready to present a small one, anywhere…

O.N. …like musical ambassadors of Goa!

E.M. We would like to be that!

Western Classical Music Scene in Goa

O.N. Father Miranda, how do you see the western classical music scene in Goa?

E.M. Well, first of all, I would say that to have a taste for Western classical music, you need to have a certain preparation, you need to have a certain musical education. In Goa, there are people who enjoy classical music. And it all depends on people, taste, education and promotion… it all depends on the family… I mean, I really like classical music, but why is that? Because when we were little – we are eight brothers and sisters – my father was very fond of classical music. It was at a time when there was nothing, nothing... when we were little children, there was only a gramophone... and then he would play, he liked to play that, and talk about that music... Well, there was music that we liked and some other that we didn’t like. But my father always instilled in us this taste for music… ‘That’s a beautiful Beethoven melody; that’s a beautiful Mozart melody’, he said… and he sang it himself. There is, therefore, the cultural climate of the family that contributes greatly to the promotion of classical music.

In the seminary, music was and still is a subject. You have to study music and pass in that subject, if not, one wouldn’t be ordained... My other brothers who went to high school at that time had a music academy there. There was choral singing there, in high school. Home and school: all this contributed to my brothers’ and my liking for classical music.

But the taste for classical music is not so widespread throughout Goa. We like to listen to it, but we don’t bother to appreciate it so much: that’s what’s lacking among us.

O.N. Father, you have been part of Kala Academy’s advisory board for a few years… What is left to be done before we seen an improvement in the level of teaching and musical culture?

E.M. Well, I would say that we need, first of all, a person with the highest musical academic training… A good musician has to know how to write the music, harmonize the music; a good musician must also know how to compose music and then he must also eventually know how to direct, and encourage others to sing and play. There are so many aspects. To do so, you have to have a degree at a higher institute of music…

Contribution of the Goa Church

O.N. Well, what is the Seminary’s contribution towards the promotion of sacred music and towards the development of the musical sense of the Goans?

E.M. Ah, I would say in my day it was western music all the way; and Gregorian music… All that was part of the curriculum. I don’t know how it is nowadays.

I had good teachers… I had a teacher called Father João Baptista Viegas: he was self-taught; he was a good musician and he himself learned to play the violin and teach music from Dominic Pereira. This was a great musical figure, a violinist from Porvorim; he was a family friend of Dominic Pereira’s. He learned from him, and he played the violin himself. It was a pleasure to see how Father João Baptista played the violin and taught the students.

Then, at Rachol Seminary, I had maestro Camilo Xavier: he had passed through Rome where he learned music and did a lot for the cause of music in Goa.

Now, the Seminary, where priests are trained in music, has contributed a lot. I would say, a musical culture was developed through the Goan clergy.

Well, the Church has always had the liturgy in mind... the priests and musical formation in function of the liturgy. Hence, in order to dynamize the masses artistically, the liturgical services, the liturgical acts, music was taught to the students and the priests.

Culture always starts with religion; religion a key to culture. This contributed a lot to, let’s say, a musical atmosphere that exists in Goa, through the priests. There are also lay people – so many lay people who have learned music and made their contribution. But then, that’s the role of the priests: each one in their respective parish builds the infrastructure of a parish choir. And the church choir is the group that gives musical support when the whole assembly sings.

O.N. But it’s not just the liturgy, it’s not just the parish; but in society, too, there are examples of how the church has contributed to Christianize certain local songs and dances…

E.M. Yes, it’s always so. In society there is always an interaction. There are the principles of the church… well, why can't you give it a very typical Goa look? For example, khell tiatr, which has music… it is always the music of the Christian community… let’s not forget that… so I would say religion has played an important and fundamental role in the formation of typical Goan music…

O.N. Exactly! And what are the initiatives of the modern church in Goa, towards dynamizing musical talent?

E.M. The Church of Goa has taken great care to see that the parts of the Mass, or liturgical acts, which include antiphons, and other musical things have musical backing. Hence, new melodies and arrangements are composed and new musical groups formed.

O.N. They say that our Gaionancho Jhelo is one of the best here in India…

O.N. They say that our Gaionancho Jhelo is one of the best here in India…

E.M. Yes, because Gaionancho Jhelo, above all, comprises many new lyrics and old lyrics, and everything is well tucked in a bouquet of very beautiful lyrics for use by the liturgy…

The Goan Motet

O.N. We cannot end without a word about the motet… Father, may I know what is the originality of the Goa motet!

E.M. First of all, the motets of Goa were composed in the same spirit in which the motets of Europe were composed. The motet of Europe was a song whereby people sang and at the same time reflected and ruminated on the biblical text relating to the respective feast. But in Goa the motets were limited to the Lenten season.

Now the Goa motets are not very difficult; they are beautiful and very well made. People who can read music can meet, and easily perform a motet. The musical accompaniment always includes violins, clarinets and the double bass…

O.N. In Europe, they were a capella…

E.M. Yes, but not all. For example, “Jesus, joy of man’s desiring”, by Bach, is a motet, as you know, from the feast of the Visitation of Our Lady…. The melody was simple. Bach’s contribution comprised the introduction that he wrote, and then he wrote an interlude and the final part, and that turned out into such a big piece. Therefore, it was a motet of the Visitation feast of Our Lady.

These motets of ours are just the same: a small musical motif, which has an accompaniment, and introduction of musical instruments; then they are sung, that is, repeated, then there is an interlude, and an ending. That’s it – the structure is very similar to that of the Western music motet, from the cathedrals of Europe.

O.N. Father, I’m afraid we’ve reached the end of our chat. Sorry to have to stop. But, before we close: you will certainly agree that the harvest is great, but the workers few…. What is your message to our people? What’s your plea?

E.M. First of all, thank you very much for this opportunity to speak here in your studio…

My message would be as follows: we are very proud to be musicians. Let’s uphold this tradition; let’s work in order that our new generation, our next generation, learn from what we do.

Now, there are so many young people in our parishes, whether or not they have a musical education, let’s give them the opportunity to be part of the choir, go there and learn a musical instrument, and come with that instrument to the church, and eventually on to the platforms offered to them.

My Stuti Choral Ensemble as well as the Goa String Orchestra will always be a platform for those who want to sing, each according to their ability… Come, you are always welcome!

I would love parents to take this task of taking their children to schools and showing them good musical programmes in our cities or elsewhere, such that younger people gain a taste for that, and then we would have a new generation of people.

O.N. Thanks again, Father Eufemiano, and long live the Goa String Orchestra and the Stuti Choral Ensemble! Thank you very much!

E.M. Thank you!

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa - II Série - N15 - Março Abril de 2022

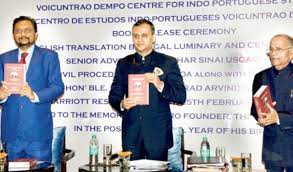

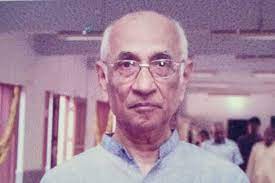

"My dream is to see Goa’s Civil Code extended to the Indian Union," says M. S. Usgaonkar

ON: What does the ‘dream’ that you talk of in the Preface to your book mean to you and to our territory?

MU: Well, before I talk about my ‘dream’ I would like to clarify that when Seabra’s Civil Code [1867] was published, it did not have the chapters that I am going to stress on, as these were fruits of the Republic in 1910. Thus, the Portuguese Civil Code was a product of the Constitutional Monarchy; the law of Marriage, the law of Divorce and the law for the protection of children were specialties produced by the Republic. The Portuguese Civil Code did not have the concept of divorce; it simply dealt with the absolute separation of property.

ON: According to you, why didn’t Seabra introduce Divorce and, instead, dealt only with Separation? Was it through the influence of the Catholic Church?

MU: I don’t think so… The concept did not exist at the time. Divorce evolved much later.

ON: So, in 1910 all communities had access to the law of divorce...

MU: Yes; but the Church prohibited it, because one of the Articles states: those marrying through the Church are not entitled to divorce. This provision was later stuck down by our Courts because one could not discriminate between two communities.

ON: Well, the Civil Code would not discriminate between communities, yet it appears that the usages and customs only of certain communities were safeguarded in the Code....

MU: This was not about the usages and customs; this was a part of the law. Divorce (earlier it was Separation) was made part of the special legislation that came into force in 1910, after the Republic.

ON: Could you throw light on the usages and customs that were safeguarded?

MU: They were excluded in 1880, that is, before the Republic.

ON: Some examples of what was safeguarded…

MU: For example, one could marry at a predetermined age, which was reduced. Later, this law was extended to the Catholics also, because they pointed out that there was a tradition or custom to marry at an early age and that was permitted by the State.

ON: What was the age?

MU: The girl could marry at the age of fourteen.

ON: And the boy?

MU: At the age of sixteen.

ON: Is it true that members of the Hindu community were permitted to have more than one wife?

MU: There was a restriction. It required the consent of the earlier wife; and she had to be childless. Only then the second marriage was permitted; but this was struck down by the Portuguese law in the year 1952, on the grounds that polygamy had long been abolished.

TRANSLATING THE CODE

ON: Let’s talk a little about your translation: how long did it take you?

MU: Not long… just twenty years.

ON: Twenty years!

MU: Well, the total number of Articles of the Civil Code is 2538. There is also the Civil Procedure Code and miscellaneous legislation regarding the usages, customs and others which total up to more than 4000 Articles.

ON: So, yours is a translation of the whole of the Portuguese Civil Code…

MU: Not only of the Code but also of other laws that were published later…

ON: … which are connected to the Civil Code and to the Civil Procedure Code…

MU: Yes, the Civil Procedure Code, too, which has 1580 Articles. The reason for translating both the Codes is that the Civil Code alone is not sufficient; the Civil Code provides only the substantive aspect of law, but the enforcement or implementation is done through the Civil Procedure Code. Courts and others must follow the Civil Procedure Code, so the Codes are complementary.

The Code of Civil Procedure was repealed in the year 1939; the whole of it was the work of Prof. Alberto Reis and it was in force at the time of Liberation… At a conference at Simla, organized by advocates from the Indian Union, I had the opportunity to highlight the advantages of the Portuguese Civil Code and how it serves to decide cases much faster.

ON: But in Goa today only a part of the Portuguese Civil Code is in use, isn’t it?

MU: It was in use, but later it was gradually substituted by corresponding Indian laws.

ON: Which are those laws?

MU: For example, the Transfer of Property Act, Contract Act which formed an integral part of the Civil Code stood pro tanto altered.

ON: So, today, the Code is in use mainly regarding family laws…

MU: Yes, the law of marriage and divorce is unaltered. Fortunately, what existed here was repealed neither by the Union of India nor by the State government, except that every time an Indian law was introduced, the respective provision of the Civil Code was repealed. For example, the law of pre-emption… when an individual sells his right without giving preference to the co-owner. This is not provided for in the same way under the Indian law. The problem which arose was to see whether this provision of Portuguese law prevails or not. The courts said that it does prevail since a similar provision does not exist in the Indian Civil Code.

ON: In Portugal, is the same Civil Code still in use?

MU: No, it was changed entirely, in 1966, influenced by the Germanic theory… When Napoleon Bonaparte prepared a Code and appointed persons, he said that the Code had to use simple language, such that the public could easily read it. In contrast, the Germanic jurists said that eventually only the jurists should read the Code and not the public.

GOAN CONTRIBUTION

ON: This Code is a Portuguese legacy, but Goa is also connected to the Code, through a Goan – Luiz da Cunha Gonçalves – who has contributed a lot, thanks to his Treatise on Civil Law... Would you like to throw some light on this jurist?

MU: Of course! He writes in the Preface to the first volume: “More than sixty years have elapsed since the publication of our Civil Code, but whereas in the interim period many treatises and commentaries have been published in the main countries of Europe, especially in France and Italy, here in Portugal the scientific work in this branch of legal science has been scarce, fragmented, superficial, nothing to compare even with the treatises of French classics, nothing on a par with the modern treatises. It was therefore imperative that alongside our Civil Code, one of the best in the civilized world, an intensive and extensive work should emerge, of the kind that I have referred to. Nobody will fail to acknowledge it, and convinced that I will be rendering good service to the Portuguese legal science and the country, I will not hesitate to try and execute the work, presuming that I will be helped by ingenuity and art.”

ON: It is evident from the host of names featuring in your book, right from the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, that your book and your translation of the Portuguese Civil Code did evoke a lot of interest…

MU: Yes, Justice Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Justice Couto and others have appreciated the translation. I can say that one who was really in favour of the Civil Code for Goa, Daman and Diu was Justice Chandrachud. He appreciated the law which existed, especially those three volumes, Marriage, divorce and Law for children, and he said thus: “The Uniform Civil Code remains today a distant world. In my view it would be a retrograde step if Goa, too, were to give up uniformity in its personal laws which it now possesses. Fortunately, as it appears now, the Portuguese followed a different policy in the matter of personal laws than the British. The Civil Code enacted by them covering inter alia family laws applied to all the communities living in this Union Territory except that the customs and usages of non-Christians were saved to a very limited extent. I am quite aware that the Uniform Civil Code of Goa, though it provides an ideal for the rest of the country, creates problems for the Union Territory of Goa itself. The special family laws operating in Goa which are different from those which operate in the rest of the country give rise to the peculiar inter-state conflicts of law. But this did not despair us because inter-state conflict of laws is one of the most perplexing aspects of American Federalism. The conflicts could be minimized by bringing the Portuguese Civil Code in line with some of the central statutes on the subject, at least in basic matters.”

ON: The Constitution of India states that the Civil Code ought to be introduced in India… You have been the Additional Solicitor-General of India. Do you think that the present social climate is favourable, and there have been efforts in that direction, or does the directive remain merely in the pages of the Constitution?

MU: Frankly speaking, till today no steps have been taken. It is an embarrassment to note that even after sixty years nothing has been done. However, the outcome of the Portuguese law was considered when there was a conference between Portugal and Goa, and judges and professors from different universities came here, and everybody spoke and appreciated the existence of the Civil Code. The conference took place when I was the Additional Solicitor-General of India.

ON: Oh! So, it was a very special event and an important step!

MU: After Independence or Liberation, as they call it, Parliament enacted a law, and it was mentioned that all the laws which are maintained are Indian laws. That was thus the first step for the maintenance of those laws – they could be repealed later, but fortunately till today the laws on marriage, divorce and [laws for] children have not been altered by the state. I have to say that there were efforts to discard it but what mattered was what the then Chief Justice of India Justice Chandrachud said: “It is heartening to find out that the dream of the Uniform Civil Code in the country finds its realization in the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. How many outside are aware of this I cannot guess.”

DREAM

ON: Senhor Doutor, one last question: we have seen that the Civil Code is a legacy of the Portuguese. For your part, the translation of the Code is your legacy to the Indian Union.

MU: Yes, exactly. For as long as I live, it is my obligation to work to ensure that it shall continue.

ON: You were speaking of your dream: when would your dream be fulfilled?!

MU: My dream has three facets: first, the marriage must be compulsorily registered before the Civil Registrar, and this gives protection to the family. In the rest of India, this is done before the Hindu priest (Bhat), but it does not serve any purpose. Second, the regime of communion of properties, too, does not exist in the rest of India, and the third: reservation of the disposable share of legitimes is a system which maintains the balance, because half-share is reserved for the family and other half can be disposed of by the testator to whosoever he or she wants.

By introducing the legislation which is in force in Goa, Daman and Diu, justice can be done to all, and the interests of the children and wife can be protected. The concept of moiety which exists as per Portuguese law is recognized under section 5A of the Income Tax Act. This law is maintained by the Indian Union, and the payment of Income Tax by Goans is made, with due regard to the regime of communion of assets, as contemplated by the Portuguese Civil Code.

ON: But it seems that during the last two or three years there have been some problems in this respect.

MU: What problems?

ON: The Income Tax officers do not accept this concept of division of assets.

MU: It is not permissible to ignore the legislation; in fact, it is a violation of the law.

ON: They say that one cannot make a special provision only for Goa...

MU: They cannot be fail to comply with section 5A of the Income Tax Act. In fact, one of the Income Tax officers appreciated it and his subordinates did not want to accept it. He said thus: “If you do not accept, I will insist on making it applicable for the whole of India.”

ON: This brings us to our last question: the beautiful dream you have for India, when do you think it will come true?

MU: I do not know, but, frankly, I am trying to see that my dream is fulfilled. I will continue working till the end.

ON: Senhor Doutor, let me take leave of you, wishing you good health and many more years of work in this field. Thank you very much.

Acknowledgement:

(1) For original chat in Portuguese, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i62XuPeTQuc (2) Translated by Tolentino António Colaço (3) Chat show photographs by Emmanuel de Noronha (4) First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 13, Nov-Dec 2021, https://casadegoaorg.files.wordpress.com/2022/01/revista-da-casa-de-goa-ii-serie-n13-novembro-dezembro-de-2021.pdf

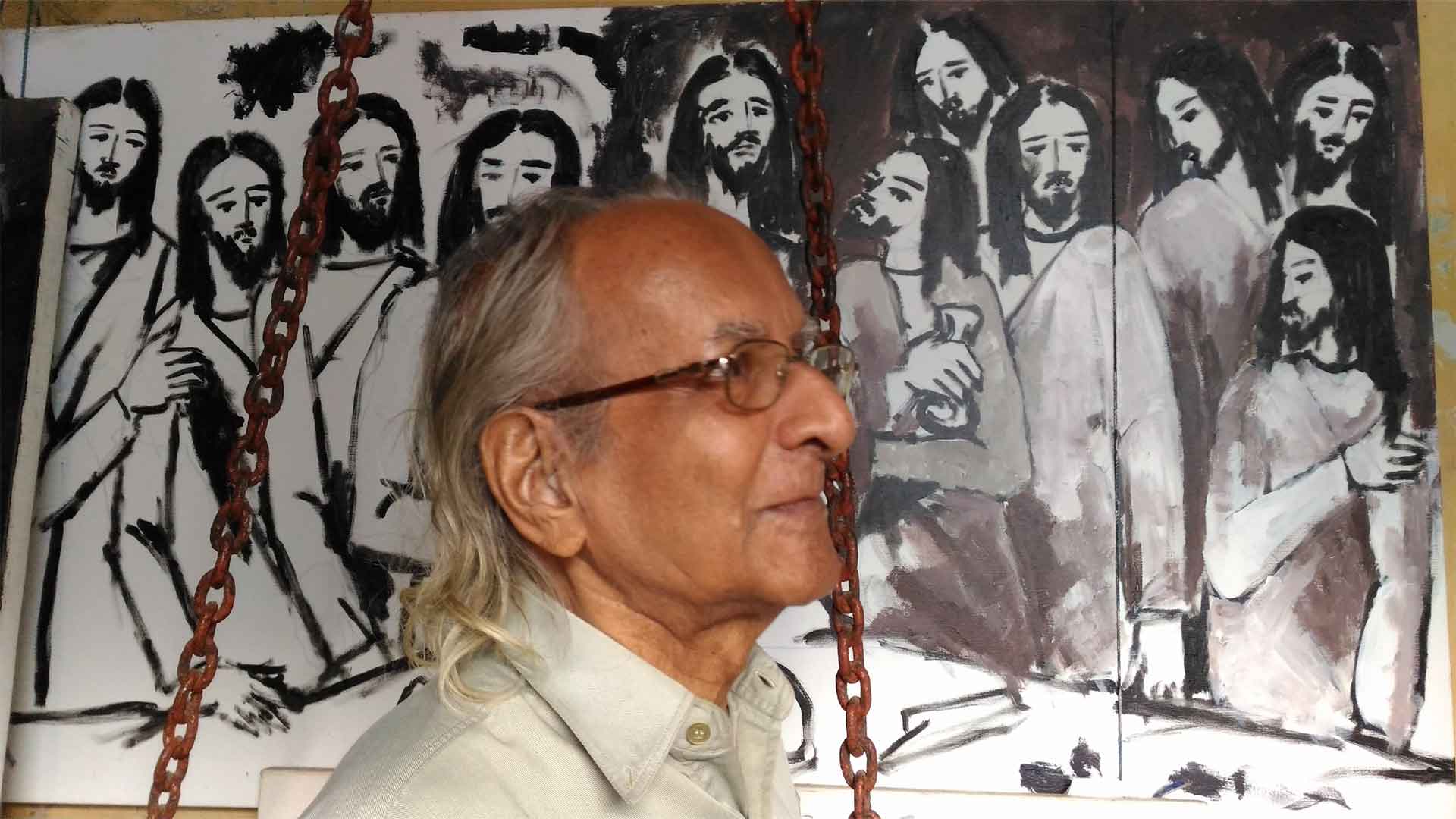

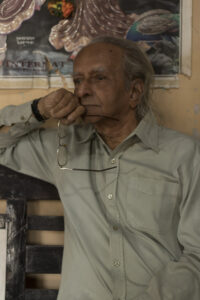

Navelcar, aka Ganesh

On a rainy morning in June [2018], we went up to the village of Pomburpa, taluka of Bardez, on a visit to the well-known Goan painter, stained glass designer and ceramist Vamona Ananta Sinai Navelcar, whose pen name is Ganesh. Despite his grey hair, he was a picture of rare vitality, and in this chat he comes across as enchantingly feisty. He invited us to see the inner patio of his house which doubles as his atelier.

For the original chat show in Portuguese, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rMgblHr5gk4&t=1s

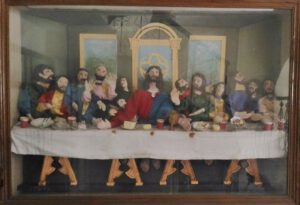

ON: We are face to face with a canvas [Last Supper] that you are working on… I suppose it’s your most recent work...

VN: I started it a week ago and have to deliver it in the next two days...

ON: You work at top speed!

VN: It feels good to work. I have worked on many Last Suppers – more than 30, in Portugal and here…

ON: Do have a penchant for Last Suppers?

VN: Yes, for Christ! At 8 years of age, I used to read the Bible in Konkani. I was surprised to see what a fine figure Christ is! I became more of a Christian ever since, a disciple of Christ indeed. I think I have nothing of Hinduism, nothing, and I belong totally to Christ…

ON: So you have a relationship...

VN: Yes, yes, there is a mystic relationship between me and Christ.

ON: Will this canvas too be signed ‘Ganesh’?

VN: Always Ganesh. None of my paintings bear my name alone. It could bear my name but this is always followed by ‘Ganesh’.

ON: Why ‘Ganesh’?

VN: Ganesh was my elder brother, who died at 16 when I was 8 years old. He was my guide.

ON: Did he inspire you to paint?

VN: My father wouldn’t allow me. He wanted me to be a doctor – like Hindus always do. I used to paint on the reverse of the calendars and would hide them when he came.

ON: Do you still have those calendars?

VN: No longer. After so many years… Well, now they would have been worth a lot.

ON: Indeed. But what was your father’s grouse against painting?

VN: I think the Hindu community holds art in contempt.

ON: Well, the Hindu civilization has great works of art to their credit… Ajanta and Ellora, for example, and so many other places.… Why the contempt, then?

VN: They are materialistic... What money does art fetch you? Medicine does!

ON: If not an artist, what would you have been?

VN: If not an artist today, I would have continued to be an employee of Chowgule’s…. After Matriculation, I began working there; I came across many people, until one day came the inauguration of the Chowgule Mines. Chowgule asked me to draw two portraits: one of him and other of the Governor. I did so. At the inaugural ceremony, the Governor asked the painter’s name; Mr Chowgule said it was one of his employees. I was called. The Governor was Bénard Guedes… the first thing he asked me was if I would like to study Art. If so, I could go to Portugal, but I said I would prefer Sri Lanka or Karachi… He said I should go to Portugal, and I said no. He then gave me a month’s time to decide, and thus I felt compelled to leave for Portugal. I couldn’t speak Portuguese very well then.

Stay in Portugal

ON: Did you complete your Lyceum in Portugal?

VN: There I did the 5th to the 7th Years of Lyceum; I did it in two years.

ON: After the Lyceum, did you move on to the School of Fine Arts? And how long was the course?

VN: It was a five year course. First it was the general course, then the complementary course. And for the admission test, one day as I was practising drawing, the teacher commented: ‘My friend, your drawings are poor. It won’t be a good idea to answer the admission test this year.’ After a week or so, he had a different opinion. My colleagues too were surprised to see a big leap forward from my first drawing. I stood second in the admission test.

ON: How was the Fine Arts course?

VN: Good. But those teachers knew nothing about other arts, the Oriental arts, Chinese and Japanese; and that India is another world, with a different culture. There was, however, a brilliant teacher, architect Frederico Jorge, who said ‘You have an original palette, and bright colours! You have a style of your own. Follow your path.’ Then came the Invasion or Liberation of Goa, or whatever you call it. I was stumped when a Goan asked me a very roguish question. I told him that I had nothing to do with Goa, and that the Goans were to blame for whatever had happened, for they never spoke their mind but remained mum. My scholarship was cancelled; they wanted me to speak out against India. Why would I speak out against India?

ON: After that you went to Africa…

VN: I had to, because the Government had cut off my scholarship, and there, instead of being posted in Lourenço Marques, I was sent to Nampula. I was stuck there for nine years, without a transfer. The Director lamented that despite being the best qualified teacher I was posted up north.

ON: That was politically motivated, wasn’t it?

VN: Yes, but I wasn’t disappointed. Truth always prevails.

ON: Satyameva Jayete [em sânscrito: ‘A verdade sempre triunfa!’].

Teaching career

ON: Were you happy to be a teacher?

VN: Yes. My aim was to understand the student’s technique or to guide them in using their technique, with none of my influence. Or else, they would just be a carbon copy of the teacher…

ON: Well, you let the student enjoy all the freedom!… And how did Africa influence you?

VN: Yes, there is an inadvertent influence of Africa on my paintings.

ON: And what about the people of Africa?

VN: They are a fantastic lot. To me, Africa is the land of Christ…

ON: In what way?

VN: To me, each African face is the face of Christ. Even while in Portugal I didn’t feel any Christian influence as I did in Africa…. Africa is Christ’s Paradise.

ON: That’s a nice expression… Did your style evolve?

VN: Yes, there has been an evolution; and I never repeat myself. What I draw today and tomorrow is completely different.

ON: Do you paint only on canvas?

VN: Really speaking, my specialisation is Stained Glass, a very difficult technique.

ON: Which would you regard as your greatest painting?

VN: None. I’m never happy with my work. I draw but am never happy. I do one and am not happy, another, and still not happy. Some say ‘this work is better than that work’ but I’m never happy with what I’ve done, never! And the day I begin to feel that I’ve done my greatest work it will spell defeat. ‘I am nothing, never shall be anything.’ These words of Pessoa opened the path of my life.

ON: What’s your work schedule? Are you at it every day or only when you feel like it?

VN: I am practically always at work, either drawing or painting.

ON: They say you used to sign your works as ‘Ashok’.

VN: That was in the 1950s and 60s; now it is ‘Ganesh’.

ON: Are there any particular colours that you like best?

VN: Blue, which is spiritual; and red, which represents violence.

On Three Continents

ON: You've been called "an artist of 3 continents". Did you travel a lot?

VN: No; Portugal, England, a bit of France, Italy…

ON: Which artists do you admire?

VN: Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Cezanne, Van Gogh…

ON: Do you think artists are different from others, think differently?

VN: Yes. They have a different perspective.

ON: It’s clear that you are a sincere man, and you like to stick to the truth.

VN: I speak the truth, and that’s why I find myself in the present condition; if not, I would have advanced further.

ON: But your work will be remembered for ever!

VN: Do you think so? My position as an artist is significant. But what has the Government of Goa done for me? Nothing! Today I would have preferred to be in Africa and never to return to Goa, never! It’s terrible. I acknowledge my defeat for having returned to Goa. I have to be frank, right?

ON: Oh yes! What were the other options open to you?

VN: To go to Africa and to stay there.

ON: Are you still in touch with your students?

VN: Yes, with many of them. The Mozambican Minister of Foreign Affairs, Armando Panguene, is a great friend of mine. And his wife was my student at the Lyceum. She is not an artist. She is an Ambassador. A very good lady. She is Armanda, and he is Armando…. When I speak of Mozambique… I get that fever. Wanted to go there…

ON: What was your most memorable experience about Mozambique?

VN: Fraternal friendship.

And as we were about to leave the lovely inner patio of the Navelcar house in Pomburpa, the Master said:

VN: This place is my everything: it is here that I read, sleep, rest…

And we soon got into other details of the Artist…

Navelcar Family

ON: How old is your house?

VN: More than 400 years old.

ON: Is your family from Pomburpa or settled here?

VN: My family hails from Navelim, Divar. They settled here four hundred years ago.

ON: So you were born here, started painting here, and grew up here... And which was your favourite spot?

VN: It was right here.

ON: Well, we find ourselves precisely at the spot of your inspiration…

VN: (Smiles) We would sit here, open these doors and contemplate the rain clouds flying over the house, creating forms that I would relate to the legends of Ramayana and Mahabharata. That influence exists in my works.

ON: Do you like music?

VN: Of course, don’t even talk about it! Western classical music, Mozart, Tchaikovsky…. and the Fado. ‘Aquela janela virada para o mar’ (‘A window with a view of the sea’)… Mourão… and many others… Amália Rodrigues…

ON: And well, here is a window with a view of the river!…

VN: Precisely. I remember Amália. ‘Aquele moreninho’, she would say. When I wasn’t there she would inquire about my whereabouts… She was a simple person, without any airs.

ON: So you knew her personally. Did you meet her when she visited Goa [in 1990]?

VN: Yes; and I offered her a drawing of mine, at the Kala Academy.

ON: So, when did you leave Portugal for Goa?

VN: In 1976. It was a big mistake…I’ve got some friends there. Very good people!

Personal Preferences

ON: What is your favourite food?

VN: Bacalhau [Gomes] de Sá, sausages, too, and beef.

ON: Well, thank you very much for your time, friendship and generosity.

VN: Today is a very significant day. I am here with friends who have deep friendship towards me and towards Art. Hope this will not be your last visit…

ON: Surely not!

VN: I am very grateful to you for your visit.

ON: The pleasure and honour is ours.

VN: And mine too!

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, II Series, No. 14, Jan-Feb 2022)

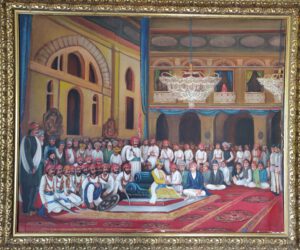

The Dhumes: Portuguese Diplomats at Peshwa Court

“Maintaining good communal ties in Goa is a crucial issue”, said the late Naraina Sinai Dumó (a.k.a. Narayan Sinai Dhume), in a chat with Óscar de Noronha, on the radio programme Renascença Goa.

Use the following link to listen to the original chat in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=renascenca+dumo

ON – Let's talk about a very important period in the history of Goa when the Dumó family had three diplomats. What information can you give us about this?

NSD – I only remembered now, at this moment, that there was a pamphlet published by Dr Panduronga Pissurlencar of the Historical Archives, titled Agentes Hindus da Diplomacia Portuguesa (Hindu Agents of Portuguese Diplomacy). And he indicated some characters; for example, the first one was Vitogi Sinai Dumó. It seems to me that Vitogi's appointment was more due to his knowledge about the negotiations between the Portuguese and the Indians…

ON – Do you mean the Peshwas?

NSD – The Peshwas! So the first was Vitoji, and he certainly lived in Poona; next was his son, Panduronga Sinai Dumó, and the third was Narana Sinai Dumó, whose name I bear. And he lived and worked in Poona.

ON – So, three generations!

NSD – Yes; the grandfather, father and son! And it seems to me that besides their knowledge of diplomacy, they spoke Portuguese very well. This is a great fortune. And he knew the Marathi language very well, so he could converse directly with the Peshwas. And it seems to me that during these three generations the conversations were limited to the exchange of Dadrá and Nagar-Haveli. I have heard that one of the streets of Nagar-Haveli is named after Narana Sinai Dumó.

ON – And how would they have learned Portuguese?

NSD – This is a big question mark, because there were no schools then. For me it's an enigma. But one very important thing: my Philosophy teacher at the Lyceum used to say, ‘One learns to speak by speaking; one learns to write by writing; one learns to dance by dancing….’ This is a motto I've followed throughout my life, to learn languages.

I was in the Netherlands for almost six months, where I was a scholarship holder of the World Health Organization. Just through the practice of talking to the office staff I learned a little Dutch and then I understood that the best way to learn any language is to speak. Don't go to its grammar: that doesn’t help – you won’t learn to talk. So, just talk, listen… have a keen ear, that's it!

NSD – Oh! But I did have a problem. I mean, after passing the 4th standard in a Marathi medium school, the first-born would switch to Portuguese, because he had to look after the landed properties, even if they were small. The system was as follows: if you wished to deal with the Portuguese officers, you had to learn Portuguese… and then some students would switch to English. I continued with Portuguese until the seventh year of Lyceum.

Hindus were very few. At the Lyceum, the composition was as follows: some were Europeans, children of officers, for example, the Secretary-General… I still remember the names of certain officers, like Pamplona de Corte-Real who was a secretary-general; another one was Rui Guimarães… Then there were the Christians, or, the apostolic Roman Catholics; and very few Hindus, but there was representation. Let's say, in a group of thirty there were at least eight or nine. That was the composition.

Among those nine or ten, at least one went to Portugal. And in this small percentage I remember Narana Coissoró, who was Speaker of the Portuguese Parliament and university professor…

So that was the composition; and I belong to the last batch of that composition.

ON – But why were there so few Hindus at the Lyceum? Where did others study?

NSD – Because they always thought that the best avenue for employment was neighbouring India. Portugal could offer nothing but a clerk’s job, and these jobs were so very few. Industrial development and things like that weren't even heard of. So they launched out in India for employment. And many Christian Goans went into the merchant navy, and others, the Hindus, went into the civil professions.

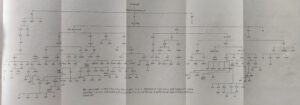

FAMILY ORIGINS

ON – Is the Dumó family from Goa, and originally from Cumbarjua?

NSD – Originally, we are from Cortalim; we are members of the Comunidade (village agrarian community) of Cortalim. We left when the first conversions took place; at the location of the first church established in Cortalim was the Manguexa temple and was destroyed. My father wrote a book after he retired: he went there and measured the dimensions. They are exactly like our temple [now located in Mangueshi].

ON – So, the temple that was subsequently built in Mangueshi [Ponda taluka] has the same dimensions! That’s interesting!

NSD – Not only interesting; but new horizons of our past are being discovered. It is indeed very interesting. You will see that there are still some Catholic families that hold their past intact: they were Sardesais, Cuvelcars, Camotins, Dumós…

ON – Do you know Dumó families converted to Catholicism?

NSD – No; but I’ve only heard that some of the Dumós who converted to Catholicism were called Saldanhas! Someone told me so, but I don't know anything more about it. But there are some families – very few – that have preserved their old data where they find their roots. It's a great joy.

Now, note one thing: in this effort to trace the past, it is worth entering into the field of genealogy. A friend of mine told me that a colleague of his, a student at the Art School, was called Maendra Álvares. His mother called her son's friends and explained the origins of the families...

ON – The Álvares are from Loutulim; and Maendra Álvares' mother was a daughter of Gomes Pereira!...

NSD – Oh, really?! From Divar! He was our family lawyer, a good family friend...

CONVERSIONS

ON – What do you have to say about the friendly relations between the various communities in Goa?

NSD – Oh! That's a very interesting chapter! First of all, the priority of Europeans was the conversion of the Brahmins. Brahmins exercised a preponderant influence. It's not that in every case there was violence and the Inquisition and things like that. Conversions also took place of their own free will. And why did they convert? Because they were offered large landed properties... You may offer some other explanation, but I think – as long as there is no other plausible explanation – that they were ready to convert attracted by those properties…. Or else how do you explain the existence of such large landowning Catholic families in Goa?

ON – Well, they are families that turned rich much later, in the 19th century, and not at the time of the Conversions [16th century]… And similarly, among the Hindu community, there are still large landowners: the Quencró [Kenkre], the Dempó, the Cundoicar [Kundaikar], the Viscount of Perném…

NSD – Well, the Quencró, the Cundoicar, and, oh yes, the Viscount of Perném! That's true…

FRIENDSHIP AMONG COMMUNITIES

ON – We were talking about friendly relations….

NSD – Yes, these friendly relations… Well, look, you’ve come here… and I'm keen on hearing this… from the mouth of the Catholics…

ON – A dialogue is the need of the hour!

NSD – Oh, yes! During my life at the Lyceum, I always thought: why does this priest have such a great affection for me? He wasn't my teacher. I’m referring to Father Armindo de Santa Rita Vás. Later, I learned that my father was a great friend of his father… The relationships were so close that, in those days, you know, a little favour done carried a lot of weight, a lot of weight…

ON – There was that feeling of gratitude!

NSD – Ah! that's it! (cries) Once, when I was in the 5th Year [of Lyceum], Father Armindo said to me: 'Look here, Dumó, listen! Would you like to go to Portugal?’ … ‘Portugal!’ My God, I was shocked. Why? Because amid the Hindu families, there was great apprehensions that one’s children would go to Portugal, stay there and get married – and live there all their life. That’s because everyone who went to Portugal to study got married there, stayed there and never returned to Goa. Never!

ON – Have you been to Portugal or not?

NSD – After my retirement I went twice. I really liked it. But I didn't get to see what I wanted to see. I had a bucket list. But I’d lost contact with my friends in Portugal. So going around in Portugal was difficult. For example, I wanted to visit and see things at the University of Coimbra… Lisbon, not so much; and some hospitals, one of those where Dr Mortó Sardesai worked: he was the Director of the Pathological Laboratory in Lisbon. And I especially wanted to see Penedo das Saudades, in Coimbra.

ON – How can this friendship that existed in Goa, between communities, continue this friendship?

NSD – Ah!!! It's a very crucial question. You see, during my days as a bureaucrat – I was in the Indian administration from 1963 to 1997, in the Health Services, first as a Rural Medical Officer and then as State Nutrition Officer – I was the first and last one, because after my departure the post was abolished. And during that time I fought a big battle with them all. Many, on listening to my story, would love to hate the Catholics – talking about communalism, and things like that….

But let me say one thing: on this path, until the last day, I had the strong, unshakeable backing, a bulwark, in the person of a Catholic: Senhor Abel do Rosário, who was Under Secretary. I salute him! He never bowed to the influence of this and that, especially of religion and community; he went by the law, and always supported me. But the political forces were so sinister that they didn't want to take the straight path. That’s a long story; it will take a few days to tell. But I would like to tell so that it is on record.

A PAST DESTROYED

ON – We've already bothered you a lot!

NSD – No, no! It's a pleasure; this is a tonic! I am very happy, very pleased to see that there are still people in Panjim – in Goa – who speak Portuguese. Why do these people want to fight the Portuguese language? They embrace English so easily, and don't want to accept Portuguese? Why? Portuguese is a language, after all. And there are liberal elements in Portugal, without which the democracy that exists in Portugal today would not have been there.

Wait a minute; I'll tell you a little story. When Dr Mário Soares came here on an official visit, as President of the Republic, my father was taken there to the President; and he took this book about the Dumós of Goa, gave it to him, and he kept leafing through it...

‘I don't understand; I don't understand anything. Why didn't you write in Portuguese? Then I would understand and appreciate.'

'Look, Mr President', said my father, 'there are thousands of books in Portuguese translated into English, and vice-versa; but there is no book translated from the Portuguese into Maratha, to show the important role that the Portuguese played in Maharashtra. The whole story only revolves around Goa, Damão, Diu, Dadrá and Nagar-Haveli!... There is nothing. Tomorrow, if there is someone interested in writing history, or in translating, what do we have! We have nothing! So, I did whatever I could do, despite my limitations.’

He got up and hugged him.

And he said: 'This whole vast Indian continent is open to you all. Why is it that instead of receiving you with open hands, we are going to receive you at the point of the sword?

Dr Mário Soares was agonised. He said: 'The whole of our past built over so many years was destroyed within a few minutes, a few minutes!'

(First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série – No. 12 Sep-Oct 2021, pp. 49-52)

State of Portuguese Language and Culture in Goa

Goa has a ‘very powerful, deep and loving connect’ with its Portuguese past, says Portuguese language teacher Maureen Álvares, in a chat with Óscar de Noronha, on the monthly chat show Renascença Goa.

Use the following link to listen to the original chat in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BRuax1W6O8w

ON: What attracts your students to the Portuguese language?

MA: In fact, when at the very beginning they opt for the Portuguese language, that is, in class VIII, I feel that they do so thinking that it is easier than French or Konkani. Well, initially I used to feel amused to hear these responses: ‘Oh, my grandparents used to speak; I adored listening to that.’ Or, ‘Aunts and uncles that I have in Portugal speak Portuguese. I would like to learn a bit more to be able to communicate better with them.’ This is another way in which students are attracted to opt for this language; and, well, with pride, I can say that Portuguese is a language that presents a stage wider than that of any other language. I do not know if Hindi, Konkani or French have the same variety of programmes, like ‘Vem Cantar’, one of the main ones; Noite de Fado, or the “Skits” that the teachers used to put up; and now many colleges do. St. Xavier’s has done it for some years now and we at Loyola’s have begun and it is now the fourth year in succession that we are going to present this programme.

ON: You mean the “Lusophone Festival of Art and Culture”, don’t you?

M: Yes!

ON: Makes sense... Goa has always been Portuguese-speaking. It really makes sense that they should choose Portuguese, rather than French… How many students do you have each year?

MA: Well, when I began teaching at Loyola, there were 7 students and luckily, the following year the number increased to 18; and we’ve even had 63 students in a division. Now we have a more ‘reasonable’ number. We have 38 students in class VIII. It is only that in class X this year we have 58 students that are appearing for the state board exams, SSC.

ON: What activities do you have as a part of the curriculum?

MA: Well, we do not have a lot of time for a lot of things, but we have a hall with a stage and the students of class IX put up small plays, a restaurant scene, for instance. And they do it with a lot of enthusiasm: acting as a waiter with a tray, the food, the drinks... It is interesting. And it is in this way that they sense a common factor in languages.

Something very interesting happened when one of my students was answering his exam. I was explaining that Salcete taluka’s spoken Konkani had incorporated many Portuguese words. And when the student could not remember the Portuguese word for spectacles, I said they should close their eyes, think, take a small break…. He immediately remembered the word óculos, and used it!

ON: Do you think that the Portuguese music competitions have also contributed a lot in this regard?

MA: Yes, they have! When I take groups to participate (always more than 2-3 groups) in competitions like ‘Vem Cantar’, for example, it is truly a lot of work. That’s because with so many places where I teach, that is, not only at Loyola’s, but also at Rosary’s, and I also travel to the higher secondary of St. Andrew’s, Vasco da Gama, I do feel tired… perhaps it is the age, I do not know.

ON: Well, that’s a missionary spirit!

MA: Yes!

ON: But the competitions have helped. For example, ‘Vem Cantar’ started more than 14 years ago, I think…

MA: That’s right.

ON: And there are participants who do not know Portuguese…

MA: Yes! As part of a group from Loyola’s, which won the first place, there were only 2 students of Portuguese. Most were students of French.

ON: Therefore, it would perhaps be fair to say that it is easier to learn the language through music, wouldn’t it?

MA: It is true, it makes sense. But in a school like Loyola, it is a bit difficult. Imagine, if we were to listen to music, the entire school would stop. Therefore, listening to music during class is not possible.

ON: But the students can do this privately...

MA: They can and should.

ON: Today we have the internet which helps by giving access to all kinds of music from any part of the world. And thus it is easier. And you, Maureen, always take good groups to contests, competitions, or wherever you go...

MA: This is because the students show interest. Frankly, they are the ones who accept the opportunity, accept the effort, and in this effort I get help from my children: my son and daughter train the students to sing. My daughter, in the area of drama, too, and the students and their parents put in efforts, come over to my home, practice… and this happens almost every evening. There are days when we are working till almost 10 at night. I could not have had better help than from the parents of those students….

O: So it is not only your individual or personal effort! It is clearly a collective effort, a family effort… The family is always helping you...

MA: Oh, you mean my family! Yes!

ON: As regards conversation… how does it go? Do you feel that by the time the students reach class XII, they are in a position to hold a conversation in Portuguese?

MA: No! And that’s simply because they are part of a larger group. And when the group is, for instance, on the playground, they either speak English or Konkani. So to attempt conversational skills among them is fine, but most have friends who have opted for French or Konkani.

I’ve also been fortunate to have a South Indian student who spoke Malayalam. When he came to Goa, he had started speaking in Konkani. He won a prize for Konkani in class V. Just imagine, at 10 years of age, he could speak English, Malayalam, Konkani, Hindi which is mandatory; and in class 8 was already learning Portuguese. So I would love to know what student, in Portugal, or France, or any other place in the world, is able to speak five languages fluently at 10 years or even at 12 or 13 years of age! Not possible.

We are a multi-lingual society. It does not enable develop conversational skills.

ON: Yes, in a polyglot society they often use words from several other languages. There are many influences…

MA: But it is like in any other language, like English or Konkani. Now in the group that is going to class IX, we have Muslim and Hindu students. And how does one enable these students to listen to the language? RTP! If not on television, there are RTP programmes on YouTube as well. They can hear the language there too.

But what helped me a lot – and I say this very often, when have teachers’ meetings – is that for students to be able to better connect with the language, they should listen to the Eucharistic service. My suggestion has borne fruit, for it is not the Catholics alone who follow their little missals in English while they listened to a Mass being held in Portuguese…. I found it interesting that the Hindus and the Muslims used to follow the Eucharistic service with greater interest than the Catholics who found it tiresome to attended Mass at church in the morning and later do this exercise at home.

ON: Unfortunately, there are no Portuguese-language newspapers here... but what about your annual school magazine: does it have a Portuguese section?

MA: Students of class X, particularly those of Portuguese, always produce articles like ‘My last year in school’, ‘Goodbye, Loyola!’, etc. – always farewells or memories. But over the years we’ve received good articles…

ON: That’s good… And before we wind up… We’ve spoken about your students, and now, on a personal note, how did you decide to be a teacher of Portuguese?

MA: Well, I never wanted to be a teacher nor did I think I would ever be one. It probably never made sense when I began, because there was a need for a teacher who could teach both French and Portuguese. When a teacher of Portuguese and who also taught French was going on leave, my sister-in-law, who knew the Principal of Loyola’s very well, asked me if I would want to teach. I said I wouldn’t mind….

ON: Congratulations! … And how do you divide your time?

MA: Well, it is difficult but when people do like what they do they do not feel that they are limiting their time to one thing or another. Well, cooking is something I don’t like to do…

ON: What! Not even Portuguese cuisine?!

MA: Neither. But I love to eat. That’s easy, because I have a fantastic family, husband and children who help a lot and are not difficult to please. So it works out.

ON: And how about your Museum? You are vital to its working!

MA: The Big Foot, right? Now it is my daughter who does most of the work, but earlier, when we had just begun, I helped my husband. Of course, the material was always in English.

ON: Do you get a lot of Portuguese tourists?

MA: More of Brazilians. We have a huge family in Portugal, so there are always family recommendations and visitors to Goa always drop by.

ON: Did you ever think of translating the name “Big Foot”?

MA: ‘Pé Grande’? No! Frankly the name ‘Big Foot’ was decided upon by the locals, but its real name is “Ancestral Goa”.

ON: ‘Pé Grande’ or, I would say, ‘Pé Gigante’…

MA: ‘Pé Gigante’, yes, it is! Also, at Big Foot we have made a great effort to present to the public what we are: Goans, and proud of being so, because we have had this very powerful, deep and loving connect with our past, when we had the Portuguese here for so many years.

Something interesting happened way back in 2006 when we visited Europe for the first time. We were visiting Aveiro where we went to this pastry shop called “O Peixinho Pequenino”. They wanted my husband and me to try out Ovos Moles. While he was packaging the desserts, he said, “Where are you from?” and my cousins answered, “They are our cousins from India. From Goa. And he said, something very curious and beautiful, “With the Goans we have a connect that comes from the womb of our mothers.”

ON: Very beautiful. And may this connect continue to flourish and enrich us.

MA: Both sides.

ON: Right! That’s all for today, Maureen! Your students are always welcome to our studio for more programmes.

MA: Thank you!

ON: Meanwhile, instead of wishing you ‘good luck’, let me say: May your students make giant strides...

MA: Thank you!

Translated from the Portuguese by Maureen Álvares

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, N.º 10, Março-Abril 2021

Lenten Traditions in Goa

ON: What do you have to say about Goa's rich tradition of Lenten music?

JLP: Well, the Motetes (Motets) are Goa’s “classical” Lenten music. They began appearing by the middle of the 19th century. They were sung on the occasion of the Santos Passos (Holy Steps of the Cross) and also during the Sacred Triduum, that is, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday. This is Goan Lenten music par excellence. Enter Vatican II in the 1960s and as a result we now have many Lenten hymns – liturgical songs to be sung in church – all composed in the Konkani language, beginning from the year 1965.

ON: What might the earlier Lenten music have been, before the Motets came about in the middle of the 19th century?

JLP: I have no idea. They must have been only hymns in Latin because the liturgy was in Latin. The Parish Schools, for example, began in Goa way back in the 16th century. No Konkani music or hymns were taught there. It was only Latin. The students of our parish schools learnt even choral songs. They could sing in polyphony and they sang serious classical music, like Palestrina and later Perosi and others.

ON: The church Mestres (music teachers) must have also contributed a lot…

JLP: Yes, the Mestres of our Churches, who were also music teachers in our parish schools, used to compose a lot of music in Latin, especially Masses. I am from Benaulim and I met one or two Mestres in my childhood – one was Sabino Rebello and the other was some Roque whose surname I forget, who was the Mestre of St John the Baptist Church, Benaulim.

ON: Are there any studies on the Motets and the religious music of Goa?

JLP: Yes, there are certain studies made on the Motets. To my knowledge, one by Fr. Lourdino Barreto and the other by a Portuguese musicologist, Prof. Manuel Morais. Fr. Romeo Monteiro has published a booklet on this.

ON: Come to think of it, the Motet and the Mando belong to the same period!

JLP: Exactly, the Motet and the Mando came up in the second half of the 19th century. It was perhaps the fruit of what we could call a “compositional spurt” among Goan composers. At least for some hundred years in Goa, motets were composed in Latin. Perhaps in the nineteen fifties or a little earlier, they began composing motets in Konkani, like “Vell Mhozo Paulo” …

ON: Who composed it?

JLP: Look, we have a curious fact here. Manuel Morais has already found a number of motets, both in Latin and in Konkani, but there is no name of the composer!

ON: What could the reason be?

JLP: What he says is that perhaps the composers were few and widely known and hence there was no interest in knowing who had composed them.

ON: Let’s say, the composer of “Sam Francisku Xaviera”…

JLP: Raimundo Barreto! He is widely known for his iconic composition “Sam Francisku Xaviera”. I don’t know of any other composition by him. He probably has some.

ON: Would there be a way of collecting all the motets?

JLP: Yes. There are bound to be other motets, in private collections. Perhaps these Mestres, no longer alive today, have left in their trunks some other motets that are not known; but I doubt we shall ever know the names of the composers. That will be very difficult to find.

ON: So, at least regarding motets, we have surprises awaiting us…

JLP: I think so too.

ON: Let’s hope so! And now, let’s talk about music composed after the Vatican Council…

JLP: There are a number of composers, starting with Fr. Vasco do Rego. He was the pioneer of liturgical music in Konkani here in this diocese. We had religious songs in Konkani, even Lenten songs, which were not motets, like “Deva doiall kakutichea”, “Jezu mhojea tujer hanv patietam”. They are penitential hymns which most probably are one or even two centuries old. But the post-Conciliar impetus was given by Fr. Vasco do Rego. He composed many Lenten hymns and he was followed by others.

ON: And who would the others be?

JLP: Fr. Bernardo Cota, Fr. Lino de Sá, Fr. Santana Faleiro, Fr. Joe Rodrigues (this one is a junior priest, but has a couple of compositions)…

ON: And there must have been lay people…

JLP: Yes, there were lay people, too, like Alcântara Barros … and there was one who had been the Mestre of Verna church: I don’t remember his name.

ON: And Varela Caiado?

JLP: Well, I know Varela Caiado as the organist of our Cathedral in Old Goa. I don’t know him as a composer. I have no idea of any compositions by him. But he was a first-rate musician. He was the organist of our Cathedral: this is all I know of him.

ON: Are there productions of Lenten music brought forth by the Diocesan Commission for Sacred Music?

JLP: Yes, there are. I think there are at least two publications of Lenten sheet music, some loose leaflets, besides one or two audio compact discs.

ON: What would be some peculiarities of the Lenten rituals in Goa?

JLP: Well, we have traditions in Goa that are not followed elsewhere. First, the Santos Passos procession is something typical of Goa, and perhaps of a few other parishes which were part of the Diocese of Goa in times gone by, like Belgaum, Sawantwadi, Karwar: these places, which now belong to other dioceses, were part of the Archdiocese of Goa; so the Santos Passos are to be found there too. If one goes to Central India or South India or North India, no, no Santos Passos there. We have inherited this from Portugal, where the tradition still exists.

Here in Goa, the Santos Passos are an interesting event…. There are ‘two Goas’: North Goa and South Goa. In North Goa, Santos Passos are celebrated on every Sunday of Lent. If on the first Sunday of Lent one dwells on the Condemnation of Christ, the second Sunday is the Ecce Homo, on the third Sunday we have the Lord carrying the Cross, on the fourth Sunday, the Lord meeting his Mother on the way to Calvary, and so on: each Sunday offers a meditation on one of the Passos or steps of the Way of the Cross. They are not the fourteen stations, but just a few of them.

In South Goa, it is only one Sunday. For example, in Benaulim, it is the fifth Sunday, in Loutulim it is the third Sunday, and so on. Here you have only one procession of the Santos Passos, incorporating one or two or three Passos of the Way of the Cross.

Another tradition in Goa, both in North and South Goa: a child sings a Veronica hymn… Earlier on, the songs were only in Latin, but now there are Veronica songs in Konkani too.

ON: And the Procession of the Franciscan Saints?

JLP: Well, the Procession of the Terceiros: this too comes from Portugal! Here in Goa we know them as Terciários. In Portugal they are known as Franciscanos Terceiros or Franciscans of the Third Order. I wouldn’t know in which part of Portugal, but they still hold this procession of the Franciscan Saints over there. Here the procession is held only in one place: Goa Velha.

ON: But I’ve heard that Rome is the only other place where such a procession is held…

JLP: I’ve heard that too. If it’s true, I wouldn’t be able to say in which parish of Rome it is held. But I can tell you that there are a couple of parishes in Portugal where such a procession of Franciscan Saints is held: fourteen, fifteen andores (litters) are taken in procession, just like in Goa. But here, no longer are they Franciscan saints alone. There are other saints: Saint Joseph Vaz, the Patron of our Archdiocese, has already been added to the saints here. Don’t be surprised if one day the procession adds in Mother Teresa, Saint Teresa of Kolkata….

ON: But how did a Lenten procession of Franciscan Saints come about in the taluka of Ilhas or Tiswaddi, which was evangelized by the Dominicans?

JLP: Well, this procession, which takes place on the Monday following the Fifth Sunday of Lent, began in the Pilar Monastery, at a time when the Franciscan Capuchos lived there. When the Monastery was shut down, all those saints or images were lodged at the Parish Church of Goa Velha… Note that Pilar still belongs to the parish of Goa Velha, and it is this same parish that holds the procession every year.

ON: As we come to the end of this chat, may I ask you for a message for the season of Lent!

JLP: My message as a priest is that we should live the spirit of Lent as it should be: a spirit of penance, saying no to ourselves, all right, but not with ashes on our heads or sitting on sackcloth as they did in the Old Testament. Ours is a more joyful Lent, because the penance I make, I make it with love and with joy: I am anticipating the joy of the Lord’s Resurrection!

For the original audiovisual version in Portuguese, see Renascença Goa at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sXlnAoKU42M

English translation by the interviewee, at my request.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), Series II, Issue 9, March-April 2021 and here with a few additional inputs from the interviewee.

Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

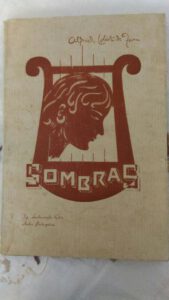

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

“The Fado in Goa is going to be a revolution!”

You can listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MUDFr-Lauqo