From Carnaval to Carnival

| To the Anglo-Saxons, ‘Carnival’ is a travelling fair or circus; to the Latins, or say, the Portuguese, Carnaval is a period of enjoyment or euphoria before Lent. Despite this Christian reference, Carnaval is far from being a religious festival. It is a cultural remnant from pre-Christian times, when the orgiastic Saturnalia was celebrated with tableaux in Rome and Athens.

The festival came to Goa via the Portuguese. At first they used the word Entrudo, of which Intruz is now a Konkani corruption. But given that Entrudo means ‘introduction’ one wonders how epicurean delights can ever be a good introduction to the austerity of Lent! For that matter, the word Gordo, as in Sábado Gordo (Fat Saturday) probably referred to people’s overeating and drinking. As a child, the expression brought to mind those silly, larger-than-life characters that walked the streets on the days of Carnaval. Of course, nowadays, it is the fat profits that the season brings in that better justify the use of the word! In town and country Although in Goa Carnaval and Intruz are sometimes used synonymously, locals know the difference: the former is city-based, cosmopolitan, sophisticated, while the latter happens in the countryside and has a plebeian feel. Anyway, revelry begins on Saturday afternoon and ends on the eve of Ash Wednesday. The festive atmosphere is more pronounced in the Old Conquests, where the Christian presence is larger; and the celebrations in the towns are noisier than in the villages. I remember my grandmother’s take on her childhood Carnaval in Pangim way back in the 1910s. Although it was marked by a lot of tomfoolery, ‘that fun was free of malice,’ she said. No doubt, there was a method to the madness of those who took to the streets in bizarre attires. They shook out talcum powder tins on friends and acquaintances, or used aluminium tubes to spray them with scented water. Youngsters – especially Lyceum lads staying in Repúblicas (hostels) – and the descendentes or mestiços, delighted in burning firecrackers or drenching passersby.[1] The city elite living around Garcia de Orta Garden Square, and families from elsewhere, went round in horse-drawn carriages and engaged in mock battles using confetti or streamers. In those days, even the governor-general played cocotes (paper cartridges containing white powder or coloured sawdust). In the 1930s, the city clubs were known for their soirées and Japanese matinées. These were informal gatherings – and ‘Japanese’ because, artist and Carnaval enthusiast Alfredo Lobato de Faria once told me,[2] Goa was then flooded with dainty Japanese products that they used on the occasion. The parties were held at Clube Nacional, which had a large ethnic Goan membership; at Clube Vasco da Gama, which was the bastion of Europeans and their hangers-on; or at the short-lived Clube Recreativo that the city merchants had set up. Such events helped the old and the young alike to unwind as they made music with family and friends; but the very pleasure of partying is said to have disappeared after World War II. In his coffee-table book titled Goa, Mário Cabral e Sá says that “Carnaval in Goa was a great leveller. Early accounts – all of them hearsay – are indeed educative. The white masters masqueraded as black slaves, and the latter – generally slaves brought in from Mozambique – plastered their faces with flour and wore high battens or walked on stilts. For those three ephemeral days, they were happy to be larger than life. And while the ‘whites’ and the ‘blacks’ mimicked each other, the ‘brown’ locals watched this reversal of roles in awe from the sidelines.”[3] The spirit of the season in our cities, towns and villages is still marked by friendly exchanges. People mix freely in a riot of colour. Way back, folks made cardboard masks and hats, covered them with tinsel, and launched assaltos (mock assaults), that is, surprise visits to friends’ houses, amusing the household and frightening unwary passers-by with their antics. Boys used chiknollis (bamboo syringes) or plastic tubes and guns, to spray coloured powder; and they painted girls’ faces, just when they least expected it, and seized the opportunity to confess their love! The village dramatist was a typical Intruz figure who spun humorous anecdotes and weaved a social critique at the itinerant khell (Konkani theatre play) with song and dance. The Kunnbi and Gauddi lot, presently free from agricultural tasks, were glad to perform, be it in the shade of a tree, in the balcony of a vacant house, or at the local bhatkar’s. One could watch them in Curtorim and Margão’s Gogol ward.[4] In fact, every village in Goa has its own little Carnaval or Intruz. The picturesque island of Divar is known for the Potekar festival.[5] And in Village Goa,[6] Olivinho Gomes describes Chandor’s mussoll-khell, a pre-Portuguese dance-theatre that has evolved down the ages. However, in the last five decades the spotlight has been on a single event – a state-sponsored parade held in Panjim and other towns.[7] The show draws thick crowds from every nook and cranny, but, unlike in the past, they now come as mere spectators, hardly inclined to participate spontaneously. Carnaval vs. Carnival It is difficult to say when Carnaval entered the Goan cultural calendar. What is well known, however, is that when the UN declared 1967 as International Tourist Year, with the slogan ‘Tourism, Passport to Peace’, Percival Noronha, a senior official of the Goa government, conceived the idea of the city parade that is held today, with King Momo announcing his reign of fun. The plan was executed by Vasco Álvares, long-time Chief Officer of Panjim Municipal Council, supported by his sons Manuel and Roberto, Francisco Martins, and others.

Timóteo Fernandes, another aficionado, was the first King Momo. The tableaux attracted tourists and locals alike. Hoping to take the show to another level, the government approached liquor and hotel industries, and their funding has since become indispensable. Clube Nacional’s Red & Black Dance held on Panjim’s main artery was the rage, and like Margão’s Harmonia and Bernardo Peres da Silva club balls, raked in a lot of money. No doubt, organising fancy dress contests, arranging costumes and decorating the venues was not kid’s stuff; it called for brainstorming and research, physical effort and coordination. But eventually it became a whole new ball game. That is how and when the traditional Goan Carnaval turned into a new-fangled, commercial Carnival. Of the old-style festival, only the slogan remained: ‘Viva Carnaval!’; its soul had vanished into thin air. With the cultural agenda thus commercialized, the festival was stripped of its simplicity and spontaneity. Those who have seen it evolve say that the comic element gradually crossed the limits of decency – and turned garish and tragi-comic! In the 1980s, the Church in Goa denounced the use of indecent attires, intoxicants and drugs under cover of Carnival. In 1987, people boycotted the festivities, protesting the delay in recognizing Konkani as Goa’s official language. The State machinery revived the festivities in the 1990s, but Carnival-weariness had already set in. Disgruntlement left a mark, at least by way of veiled messages that the floats displayed. Even so, the Carnival bandwagon has moved on, fuelled by money, feni and more. It stations itself at Garcia de Orta Garden Square, specially renamed ‘Samba Square’ for the season. There are food and liquor stalls, music, dance and revelry galore, but missing is that authentic spirit of Carnaval… In a bid to draw attention to the only Latin festival in an Indian setting, why conjure up a picture of Brazil? All one had to do was change ‘Carnival’ back to our very own Carnaval! |

[1] Fernando de Noronha, Goa tal como a conheci. Goa: Third Millennium, 2018, p. 129.

[2] See Alfredo Lobato de Faria’s interview on Renascença Goa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

[3] Mário Cabral e Sá and Jean-Louis Nou, Goa. New Delhi: Lustre Press, 1986, p. 44

[4] Cf. Vince Costa’s short film titled ‘Chotrai, khellpolloinarank chotrai’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

[5] Celina de Vieira Velho e Almeida, Feasts and Fests of Goa: The Flavour of a Unique Culture. Panjim: Self-published, 2023, pp. 24-27.

[6] Olivinho Gomes, Village Goa. New Delhi: S. Chand & Co., 1996, p. ___; Zenaides Morenas, The Mussoll Dance of Chandor. Goa: Self-published, 2002.

[7] Carnival 2025 I Doordarshan Goa I Live Telecast of the Panjim Carnival Parade, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nnvgbl-Sc_U

Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

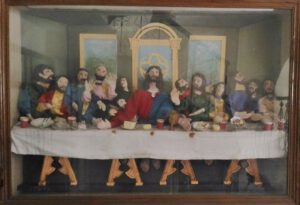

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

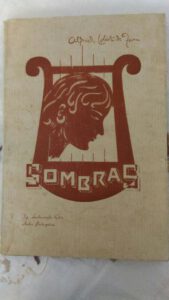

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

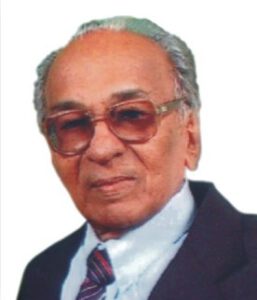

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

Why the Inquisition in Goa

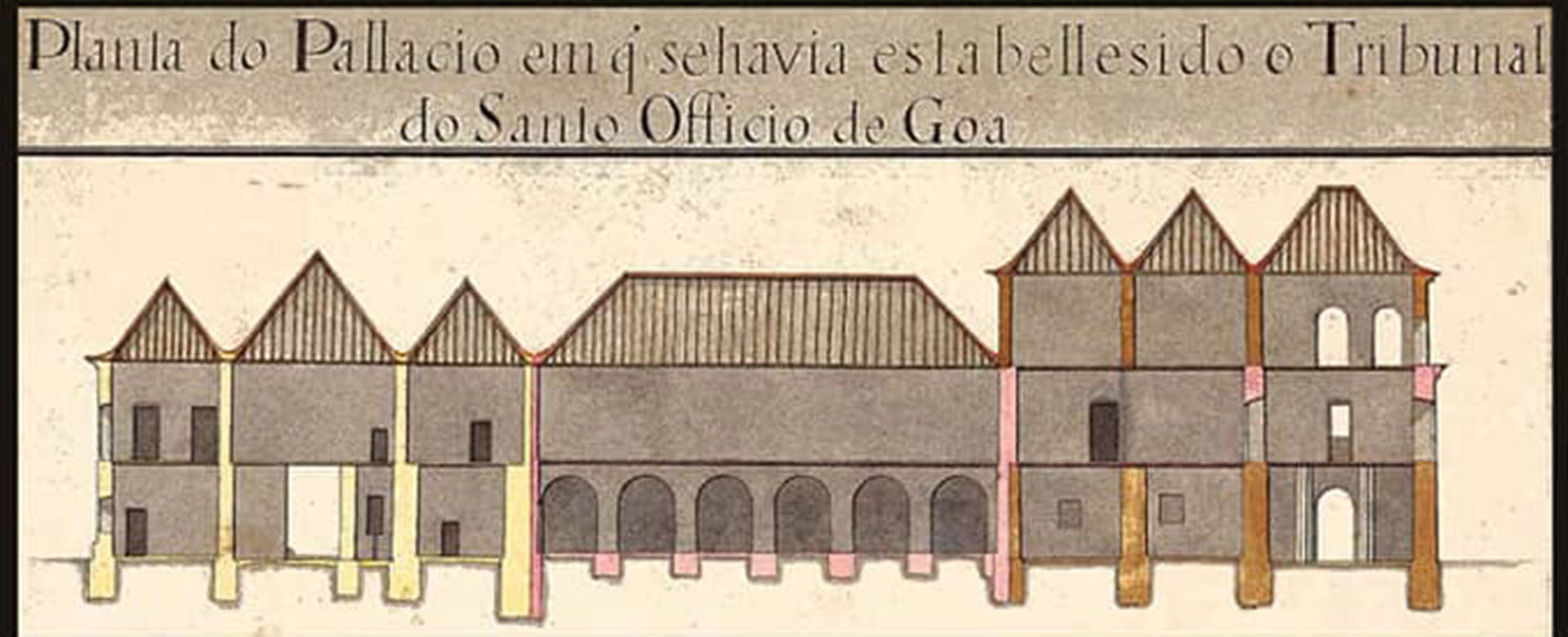

At Instituto Camões, Panjim, Professor José Pedro Paiva of the University of Coimbra provided a lucid rationale for the establishment of the Tribunal of the Inquisition in Goa (1560-1812). His talk was titled "Reasons for the Founding of the Goa Inquisition in 1560". He stated, among other things, that even prior to the arrival of St Francis Xavier the Religious had endeavoured to establish the Tribunal in Goa.

For my part, convinced that no serious student of history should depend exclusively on Charles Gabriel Dellon's much-quoted account titled Relation de l'Inquisition de Goa (1687) and Bombay-based A. K. Priolkar's expedient interpretations of the Frenchman's allegations, I asked the erudite Professor where one would find fresh archival sources to counter their claims. He pointed to the Portuguese and Brazilian archives.

Without a doubt, the Tribunal, like every human enterprise, had its shortcomings; but having said that, by no means do Dellon and Priolkar deserve a clean chit. While the testimony of the former, who was tried and incarcerated by the Tribunal, is largely suspect, the latter's narrative fails to contextualize the institution, and his vitriolic language hardly behoves a researcher. It is curious to note that his work appeared in the year 1961, a watershed in the history of Goa and Portugal.

It is a pity that there has hardly been any comprehensive study of the Goa Inquisition, particularly in the English language. And alas, just as a big lie told frequently enough is finally believed, unsuspecting readers have found themselves trapped in a web of lies regarding the nature and purpose of the Inquisition. It is heartening that a younger crop of researchers has been shedding fresh light on the subject and overturning previous findings or misplaced conclusions.

Meanwhile, as the matter in question often boils down to the number of deaths at the stake, I was keen to know details of the same. The exact figure will never be known, since the relevant papers are unavailable, for reasons too complex to mention here. However, Professor Paiva authoritatively stated that, based on the lists of names available in Lisbon, the number of trials held in Goa, over a period of 250 years (1560-1812), are reckoned at 14,000 and the convictions at 800, the average thus being 3.2 deaths per annum.

Comparisons may be odious, but can we overlook the odious crime of human sacrifice perpetrated in Indian society outside the borders of Goa during that same historical period? Some of them had religious sanction, others were committed arbitrarily, but none gave any scope for self-defence or mercy. Similarly, who can deny that the number of convictions by criminal courts far exceeded the inquisition tribunal's annual average of convictions?

Finally, those numbers pale by comparison to the political and other inquisitions at work in the twenty-first century, many of which - please note - do not have even the semblance of a tribunal or a fair trial. Hence, a sense of history and fair play are a must to understand the rationale behind the Inquisition tribunal set up in Goa way back in the sixteenth century.

Tribute to my Father

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

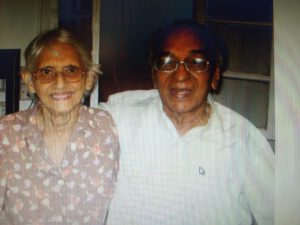

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

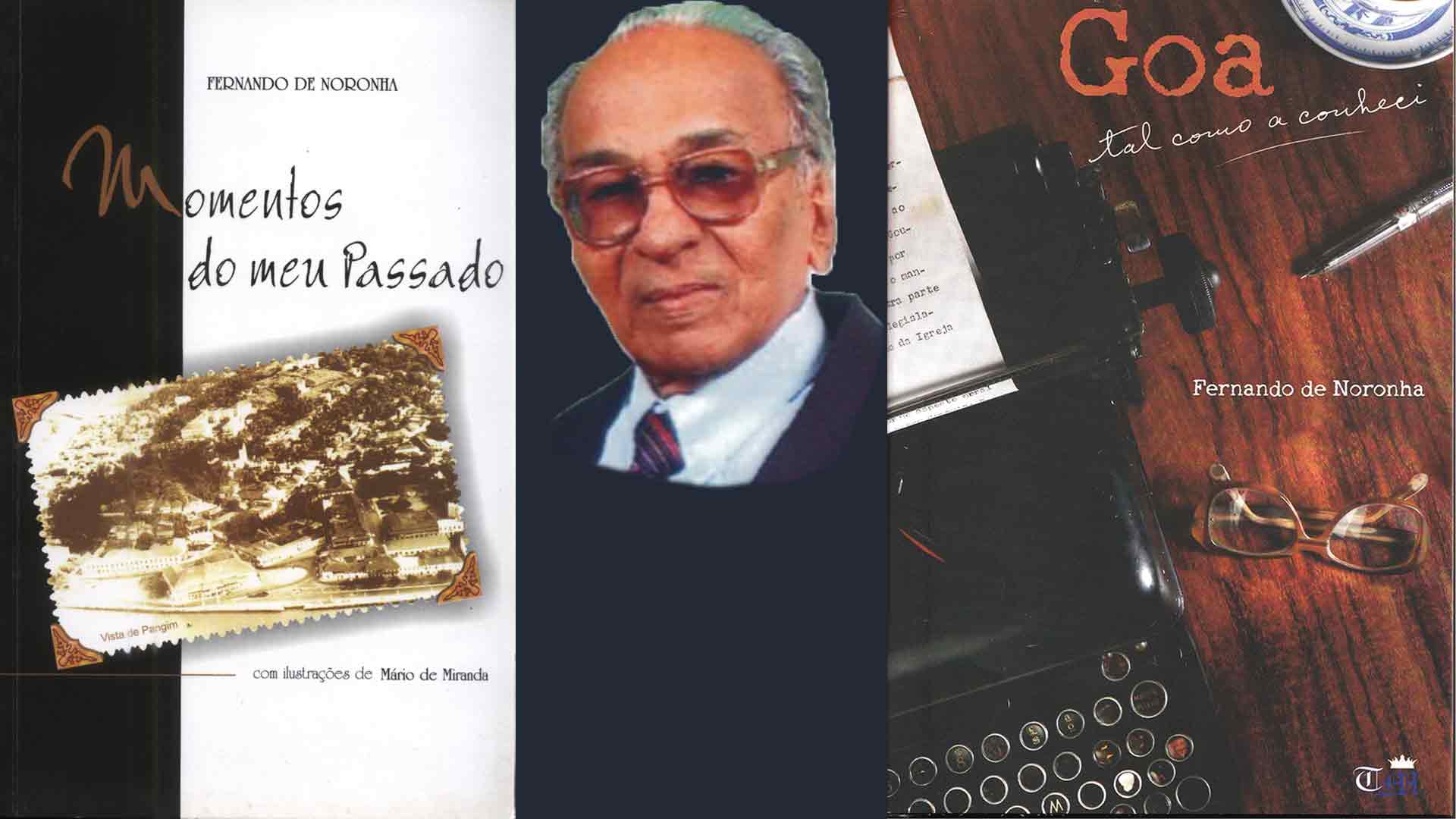

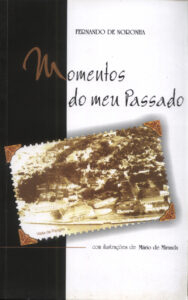

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2

The Two Abbés

Who in Goa hasn’t seen that striking bronze figure of a tall man in a flowing robe, with a lady tumbling down at his feet? Sculpted by Ramachondra Panduronga Kamat and erected next to the Adil Shah Palace, the statue is now in its seventy-fifth year. It was a tardy tribute to a nineteenth-century Goan celebrity – Abade Faria – considered the ‘father of modern hypnotism’.

For every passer-by that admires that lofty monument, there are thousands the world over who would be reminded of a literary character of the same name: Abbé Faria from Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte-Cristo. This adventure novel was published a century before that statue was put up in Panjim.

Are the Abade and the Abbé one and the same person? Faria is a surname; abade and abbé mean ‘abbot’ in Portuguese and French, respectively. The historical Faria only served as a literary inspiration for the celebrated French writer. Some parallels are obvious between the two figures but not all of them do justice to the flesh and blood Faria.

The real Faria was born José Custódio de Faria, in Goa, then Portuguese India. After eight years of priestly studies and a doctorate in Rome, he lived in Lisbon for the same number of years. Finally, he settled down in Paris, where he spent over thirty years, with a year or so in Marseilles and Nimes. In France he was referred to as Abbé Faria.

Dumas’ learned Abbé is a linguist, philosopher, and a strong-willed man. Our Abbé was proficient in philosophy, theology, history, and he intuitively discovered hypnotism; he knew Konkani, Portuguese, Latin and French; and was a resolute man. The physical attributes of the two are similar, except for their height.

The novel is set in the bay of Marseilles, where the fictional Abbé is imprisoned; the real Abbé worked in that port town as a professor of philosophy, in 1811. The former is nicknamed ‘Mad Monk’ by the prison staff; quite intriguingly, our Abbé too was derided by doctors, writers and fellow pastors for his ideas on hypnotism, in Paris (1813-19). Similarly, the Abbé’s description of lodging and boarding in jail could well be a mirror image of the real Faria’s living conditions at the Orties convent. Dumas’ inspector of prisons would be the equivalent of an actor, Potier, who lampooned our Abbé in Jules Verne’s fateful play, Magnétismomanie.

Coming now to Abbé Faria’s tunnelling for three long years: it could be interpreted as the real Abbé’s quest for ideas and materials in support of his theory of sommeil lucide (lucid sleep). When they died of fulminating apoplexy, in their sixties, both characters had their books still unpublished. The real Faria’s book De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme (Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man) came out posthumously; the remaining three volumes were untraceable, much like the jailed Abbé’s book that was never found.

While Dumas’ Abbé is an Italian, born in Rome; the Goan Abbé was born in the ‘Rome of the East’. The hero, Dantès, once journeyed to India, whereas José travelled from India to Europe, and never went back to his homeland. Interestingly, the fathers of both have important roles in their sons’ lives. Could Dumas have known that José’s father in Lisbon was under house arrest for his nativist ideas, and that many of the conspirators of 1787 in Goa met with a fate worse than death? Apparently, José’s father and Dumas himself were both republicans at heart.

Finally, the treasure that the Abbé highlights in the novel could be a pointer to the treasure that the historical Abbé Faria endowed us with, in the form of hypnotism: this has long been an invaluable aid to the physical and mental well being of humankind.

It is sad that Faria fans find it hard to separate fact from fiction: shrouded as he is in deep mystery, the real Faria comes out largely disfigured. But given that historians and medicos took no steps to fix that shortcoming, how can one fault Dumas for taking artistic licence? After all, the man who died, disdained and forgotten, on 20 September 1819, was kept alive in the pages of The Count of Monte-Cristo. It now behoves us to put the historical Faria on a pedestal much higher than the one on which he is placed in Panjim’s main square.

Celebrating Braz and Jazz

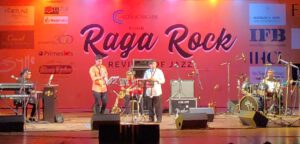

"Raga Rock" was a much-deserved tribute to Goa-born Braz Gonsalves. Thanks to this presentation by Panjim-based Communicare Trust run by Nalini Elvino de Sousa, Goa got to sing paeans to a Jazzman who keeps a low profile after decades of showmanship in the Indian metros.

At the Kala Academy, on 14 June, I was charmed by the sight of a senior citizen at the entrance, welcoming guests with a gracious smile. Many passed him by, unsuspecting that he was Braz Gonsalves himself. For sure, many jazz aficionados have heard of the man and enjoyed his music; very few would have met him in person.

A few minutes later, the very same man wearing his trademark flat cap stole the show. At 86 years of age, he regaled a packed auditorium with his magical, golden saxophone. He was joined by his good ol’ boys: Louiz Banks (who formed the great Indo-Jazz Ensemble, with Braz); Karl Peters, India’s foremost bass guitarist, and drummer Lester Godinho, not forgetting his own, musically talented wife Yvonne ‘Chic Chocolate’ Vaz, daughter Sharon, son-in-law Darryl Rodrigues, and the youngest – and perhaps the most talented of them all – his grandson Jarryd Rodrigues. “Grandfather meets grandson,” boomed Banks, who also remarked that “the legacy of Braz Gonsalves is in the safe hands of his grandson Jarryd.” They made an amazing duo.

What a spectacular evening of jazz! And the music will play on, if the revelations on stage are anything to go by: Jazz pianist Jason Quadros, Portuguese-born soprano Maria Meireles, Anthony Fernandes (bass) and the ‘cool’ Coffee Cats comprising Ian de Noronha (keyboards, bass and melodica), Neil Fernandes (guitar and vocals), Jeshurun D’Cruz (drums), Jarryd Rodrigues (alto and soprano saxophone), Gretchen Barreto (vocals), Ajoy D’Silva (trumpet), and Lester D’Souza (tenor sax).

The music segment (vocals and instrumentals) was preceded by a musical skit in which sixteen children recreated the story of Braz Gonsalves’ life which began in Neurá-o-Grande, a village my ancestors hail from. And that was an added reason for me to celebrate Braz and Jazz!

Good Friday Procession in Panjim

The 3 o’clock, Good Friday service at the city church of the Immaculate Conception comprises a poignant Crucifixion tableau.

Soon thereafter, a procession of Senhor Morto (Dead Lord) on an andor (black canopied wooden platform carrying a life-size statue of Our Lord who died on the Cross) starts off, with a statue of Our Lady in trail. It wends its way through the main thoroughfares (the church square, a section of 18th June, Pissurlencar, past Azad Maidan), making a major halt to pray at the chapel formerly attached to the mansion of a Portuguese noble family. The cavalcade then proceeds via M. G. Road and Dr D. R. de Sousa, past the Garcia de Orta Garden, and up the church stairway.

The pious march takes approximately 90 minutes. It is animated by five decades of the Marian rosary recited over speakers fitted at several points; and by Lenten hymns sung by a choir to the accompaniment of a brass band. The circuit is marked by over ten descansos (halts). At these points, penitents, all of them de rigueur, in funereal attire, flock to the two statues. Members of other religious faiths also pay their respects; many watch in awe or stand at attention (I noticed a policeman saluting).

One such halt is at a quaint chapel traditionally called 'Capela de Dom Lourenço', located behind what is now the iconic Hotel Mandovi. In times past, the chapel was part of the manor belonging to Dom Lourenço de Noronha, a Portuguese nobleman, who had acquired a large estate in the then incipient city centre. After the palatial mansion was razed, the chapel was handed over to the care and possession of the city church. Alas, the venerable structure is in a state of disrepair.

On the said route, two Hindu families (Caculó and Neurencar) traditionally offer garlands. Businesses brighten up their establishments, or simply light candles and burn incense on the adjoining pavements.

In a coda to the baroque event is a sermon (Sermão da Soledade de Maria) at a stair landing: here, from a balcony that serves as a makeshift pulpit, a priest extols the virtues of Mary and highlights her present solitude. The congregation listens in silence even while vehicle noises spoil the ambience.

The statues return to the church for final veneration. By 8 o’clock, they call it a night!

Of St Patrick’s Day and Other Misappropriations

As I walked down Panjim’s sunset boulevard, I noticed green placards hanging low on cheerless lampposts, screaming: ‘17/03/17!’ (Saturated with the political goings-on, I wondered what troika the Seventeen were now trying to trap after the Thirteen, by artful combinations and permutations, had already surprised everyone!) Soon the morning newspapers said it all: 17/03/17 – Happy St Patrick’s Day!

It was clear from the daily’s promotional lingo that a new festival was on the cards. Goa was being pushed to celebrate distant Ireland’s patron saint, like their diaspora does in Europe, America and Oceania. Goa wouldn’t stay aloof after having been flatteringly styled a “home to varying celebrations that have origins in various parts of the world, largely owing to its diverse base of residents”. It was the voice of globalization commanding participation.

Exploiting that trace of vanity in the Goan personality is something the secular press has always been quick to do, satisfying the business class and officialdom. Their advertorials have their own logic and propriety, usually to the detriment of a gullible population. And alas, by their thirst for sensation and spotlight, people do go all out for a flashy initiative in town, be it in business, politics or religion.

Would that be a proper response to the hijacking of Catholic dates and events by the secular world? If St Patrick’s were a religious feast in Goa, a church patio somewhere would have been abuzz; but there isn’t a single place of worship dedicated to the Irish saint. Regardless of all that, and in breach of the Lenten spirit, our youth participated heart and soul in a much publicised event – “St Patrick’s Day Live”, 7.00 p.m. onwards, at the Inox courtyard! I doubt other communities would have frolicked likewise if something that they regarded holy were involved.

At any rate, considering that Goa is used to celebrating at the drop of a hat, this outburst may seem like a storm in a teacup. However, it’s not about St Patrick’s Day alone. It is about how similar events are foisted on us through ingenious publicity; it is about how our Catholic youth fall prey to them so easily, cutting a poor figure on the social front and exposing themselves to risk on the spiritual front; and it is about how, often, and sadly, it is members of our community that are promoters of such far-out ideas.

Such initiatives smack of crass commercialization. Consider this. If for the purpose of any trade, business, calling or profession, it is illegal in India to use certain emblems and names that may be suggestive of State patronage; can it be licit to liberally use religious names or concepts subverting their original intent? How are St Francis Xavier or St Anthony appropriate, let us say, to a bar or tavern? And our dear St Valentine, who is the patron saint of lovers: see how dishonorably he is treated. Such absurd practices go uncontested, so commercialization has a field day.

Our lives are further made banal by the unholy alliance of commercialization and the near-total secularization of the mind. The story of Santa Claus as spun by Coca Cola speaks volumes; it is a narrative of materialism and consumerism that has chimed with all and sundry. It is a standing invitation to celebrate. With, or without Christ: that is not the question! And so it happens that the gifts of the season matter – but not The Gift! Secularization has indeed distorted the idea of divinity, if not displaced it from people’s minds; it is the opium of the people.

Yet, secularization is only the beginning. Look at Carnival. It is show business in the guise of religion and culture – simply ruinous. The powers-that-be have been portraying it conveniently as a Christian festival. For the past quarter of a century, the Church in Goa has cried herself hoarse about its pagan roots and irrelevance to Christianity. Even so, ‘secular-minded’ Catholics continue to patronise those bizarre festivities. If pagan gods Momo and Mammon have gained acceptance in modern society, there is no doubt that secularization is spiralling towards paganization.

The bottomline is that we haven’t done enough to guard the Faith; the attendant problems are a result of a deep-seated malaise within the organization. It is sad and ironic that the Church, whose philosophy once governed the nations, is herself besieged by the forces of globalization, commercialization, secularization and paganization. So the time has come for a collective realization, a genuine awareness of the gravity of the problem. This won’t be a mere storm in a tea cup but a benign tsunami that will cleanse the system, snuffing out the “smoke of Satan”. Let’s get ahead and do it prayerfully, before another St Patrick’s Day arrives.

(First published in Renovação/Renewal, 1-15 April 2017)

Lent, an irresistible balm for the soul

Haven’t we felt listless, not to say ill at ease, about Lent, sometime in our life? As a child, I tagged along with my parents to liturgical services that made little sense. Not surprisingly, on reaching the age of reason, I had to be cajoled into attending them. Then, suddenly, I got a break. I found motets, songs for the season, composed by Goa’s unnamed musicians of old, to be an absolute feast for the ears, alongside similar compositions by Bach, Palestrina and Mozart. I also discovered, quite ironically, that the Via Dolorosa in the balmy evening breeze and to the chirping of birds in the woods of Altinho was not so dolorous after all!

Much as I delighted in those two little secrets, at one point I felt an interior dryness, a sense of futility, as though I were trudging a wasteland. The saving grace came from my grandmother’s exemplary life, which was far better than precept. Likewise, my parents’ quiet commitment to the Faith, amidst their daily toil and moil, provided important insights into the valley of tears we live in. And Scripture wrapped it up so beautifully: “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not of more value than they?” (Mt. 6: 26)

Clearly, the rituals that I had cheekily dismissed yesterday changed into victuals for the spirit today. And as another season of Lent comes round, I know just how it will turn out, how they will sustain me…. Beginning Ash Wednesday, I will go to church more often than usual, for Mass and Stations of the Cross. On a hopefully bright and festive Palm Sunday morning, I will feel cheery. Yet, by evening, my mood will change hugely – as it always did when I witnessed the spectacle of the full-size statue of the Suffering Lord emerge from the immaculately white church of the zigzag stairway, to join the faithful clad in dark shades, in a penitential procession through the streets of the capital.

What a poignant start to the Holy Week! It’s the last lap of an all-embracing spiritual journey. You’ll probably catch me shaking off distractions on holy Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. Through the rest of the week, I will be all eyes and ears to the Mystery of mysteries replayed in the Paschal Triduum, from the moment of that bittersweet Last Supper on Maundy Thursday through excruciating Good Friday and triumphant Easter Sunday. Soon, the week’s darkness will give way to light and its drabness will translate into loud proclamations. The faithful will be beside themselves, singing in an unending refrain: “No one can give to me that peace that my Risen Lord, my Risen King can give.”

It pays to be fools for Christ; Chesterton’s “Donkey” is proof that there will be no regrets. The thought of self-privation, which had bugged me when young, doesn’t assail me. I find it easier now to give up a favourite food or a much-loved pastime. Penance and sacrifice, besides fostering self-discipline and tempering our desires, are game-changers. They help to boost one’s spiritual life and improve our physical health. We are led to find ways and means to step up our knowledge of our faith; perform acts of kindness and mercy, wherever we may be; pray for others, and clean ourselves inside out by means of a holy confession. Before long, we learn to slow down, while the rest of the world is in a rat race, enjoying in a fool’s paradise.

It is reassuring to think of Lent as pilgrimage toward the profound mystery of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Benedict XVI says it is also “a privileged time of interior pilgrimage toward Him who is the fount of mercy. It is a pilgrimage in which He himself accompanies us through the desert of our poverty, sustaining us on our way toward the intense joy of Easter.” How, then, can we be listless or ill at ease at Lent when an irresistible balm for our soul is at hand?

(First published in The Times of India, Panjim, 1 March 2017)

Naval Band enthrals

What we know of the Indian Navy is that it safeguards the nation’s maritime borders, enhances international relations through joint exercises, port visits and humanitarian missions, including disaster relief.

What we know very little about, however, is that the Navy prides itself on its band. They perform at events of national and international significance. Those include the Republic Day Parade and the celebrations that culminate in the Beating Retreat ceremony in New Delhi.

Interestingly, the Band, formed way back in 1945, accompanies naval ships on goodwill visits to foreign shores. It has woodwind, brass and percussion sections. String instruments include the violin and the double bass; and among the Indian instruments are the tabla and the dholak. The Indian Navy musician officers, playing in ensemble with the bands of foreign nations, double as unofficial musical ambassadors of the country.

The sixty-six men Indian Naval Symphonic Band is in concert in our State, performing under the baton of the Director of Music (Navy), Commander Vijay D’Cruz, who is of Goan origin. He is assisted by T. Vijayraj. Their repertoire includes fanfare, waltz, folk, swing, fusion, hymns and patriotic music; of which my favourites were 'Le Mariage de Figaro', 'Skater's Waltz' and 'Abide with Me'.

Commander's D'Cruz's composition, ‘Folk Tunes of Western India’, which took the audience on a journey through the states of Western India including Goa enthralled the audience. ‘American Patrol’, a popular marching tune composed by Frank White in 1885, and ‘Shanmughapriya’, a ragam in Carnatic music, followed.

Today’s show at Dinanath Mangueshkar auditorium of Kala Academy was packed to the rafters. It was beautifully compered by Genevieve da Cunha, wife of commanding officer of INS Mandovi, Captain Sanjay da Cunha, whose family hails from Curtorim.

A beautiful mix of great social propriety and bonhomie marked the event. It was a treat to see the officers and their families interacting among themselves and with their guests.