Magic Aunt Zita

When our best-loved aunt Zita left for her heavenly abode a year ago, we felt a light going out of our lives. There was darkness everywhere. She had been struck by a crippling illness for a considerable period, but magically, her own light never flickered; on the contrary, by her exemplary fortitude, she radiated still more light. I got the picture when I spent a day by her side, at her home in Curtorim, to recall the good old times and to especially thank her for all that she meant to us. In her last months, kith and kin she had not seen in a long time also had the fortune of meeting up with her.

Tia Zita spelt magic, in the positive sense of the term. She was cheery – that’s magic; she loved unconditionally – and that’s magic, too. What else could one wish for? You ask, what is the secret of all this? Her very life – lived less for self and more for others. Her unspoken motto was ‘Fazer o bem, sem ver a quem’: Doing good to all and sundry. At times she must have felt misunderstood, but she took it all in her stride, convinced that loving kindness conquers all!

St Paul exhorted the New Christians to be, ‘like Christ, everything to everybody’. To some our aunt was the Sun, to others the Moon. She burnt strong and bright as the sun, and stood by her family like a rock; and like the moon, her soft side provided a cushion to the family’s generation-next in their difficult moments. She would make light of any problem and top it off with a delectable treat!

With that perfect balance she managed home and office. Her husband experienced her self-giving love for more than quarter of a century; colleagues at office and staff at home valued her understanding and jovial disposition. She generously gave of her time, especially to her mother, and of her money to those in need. Her easy smile would turn into peals of laughter, triggered by an upfront comment or some naïveté of yesteryear. With no children of her own, she was a mother to her nephews and nieces. It was in her nature to reach out to everyone, which won her the epithet ‘Mother of Mercy’!

She was a woman ahead of her times. She studied and worked in British India and then joined the state tourism and information bureau in the Goan capital. In the early 1970s – when hardly any lady in Goa dreamed of owning a two-wheeled motor vehicle – she would ride her Rajdoot scooter to her workplace in Margão. This spoke of her outgoing personality, her initiative, and of her daring, too, especially considering that she could neither start the bike nor park it securely: a man-servant at home and a peon at the office usually did the honours!

As the first manager of the government-owned tourist cottages in Farmagudi, she once played host to our bachelor statesman Vajpayee, then a foreign minister. He praised her penchant for landscaping, while our aunt quite naturally engaged in repartee reflecting the Goan joie de vivre. All of which must have got our poet-minister to pen a verse or two!

Aunt Zita herself was not an armchair tourist; impelled by the travel bug, that slim and fair-skinned lady, who was always in step with fashion, crisscrossed India and some countries in Europe, with a relative or a friend. And after having been a ‘tourist’ all her life, in the two decades of her retirement she was essentially a ‘pilgrim’ who daily went to church for Mass and was engaged in charitable activity.

Several years earlier, a critical tryst with illness, which she was healed of thanks to a non-surgical intervention by the saintly Dr Ernest Borges, had been a turning point in her life. But her final test came during the Holy Week last year: she lay in the hospital bed – her purgatory on earth – her sweet visage reflecting Christian resignation vis-à-vis that inescapable moment of reckoning.

It is a moral certainty that Tia Zita is now in the Beatific Vision. And most certainly, too, none of what has been said here will be of importance to her; it rather will make us all the difference to realize that her life was an echo of this touching quote: ‘I shall pass through this world but once. Any good therefore that I can do or any kindness that I can show to any human being, let me do it now. Let me not defer it or neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again’ – which could well be a way for us – who are not of this world – to look forward to the treasure that awaits us in Heaven.

(Herald, 27 March 2009)

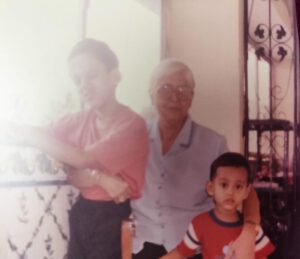

Banner pic: Isabel and I, flanked by T. Zita and T. Francisquinho, Neura, 13 May 1994

THE MAESTRO’S TOUCH

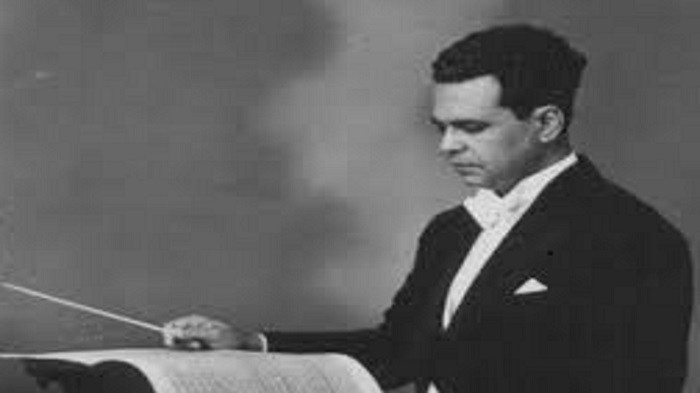

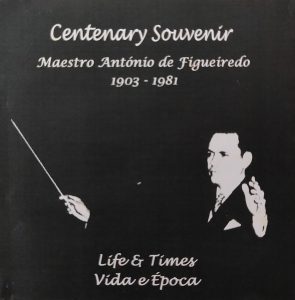

Three cheers to the first of our very own Von Trapps – on their comeback and creditable stage performance during the birth centenary celebrations of their patriarch António de Figueiredo. This Goan maestro was perhaps singly responsible for setting the Western musical scene in our land on a firm professional footing, way back in the mid-1950s. I heard he was quite a sensation in those days and exerted an important influence on the Goan people.

I heard he was quite a sensation in those days and exerted an important influence on the Goan people.

I vividly remember my parents recommending the Goa Philharmonic Choir and Symphony Orchestra, which was to perform under his baton at the Menezes Braganza hall, in 1973. It was a veritable feast for my senses as an eight year old, never mind the minimal acoustic conditions of the venue. The concert also proved to be the beginning of my love for western classical music, especially as a result of its many replays, possible for us as a family, thanks to my father who had taken the initiative to audio-record it on our spanking new Hitachi!

How I wish the local stations of All India Radio and Doordarshan had taped the proceedings of this birth centenary for the larger Goan family at home and abroad! And as a more eloquent public homage to the maestro, it would in the fitness of things to have Kala Academy’s open-air auditorium named after him who was the founder-director of the Academia de Música (now Kala Academy’s department of Western Music), and similarly, a prominent city and village street too; to have a bust of the maestro installed in the premises of the Kala Academy, scholarships instituted in his memory, and to entrust a musicologist with the job of writing a biography and putting together his musical works. The centenary CD released by his admirers is a step in the right direction, but only for starters!

How I wish the local stations of All India Radio and Doordarshan had taped the proceedings of this birth centenary for the larger Goan family at home and abroad! And as a more eloquent public homage to the maestro, it would in the fitness of things to have Kala Academy’s open-air auditorium named after him who was the founder-director of the Academia de Música (now Kala Academy’s department of Western Music), and similarly, a prominent city and village street too; to have a bust of the maestro installed in the premises of the Kala Academy, scholarships instituted in his memory, and to entrust a musicologist with the job of writing a biography and putting together his musical works. The centenary CD released by his admirers is a step in the right direction, but only for starters!

The concert also proved to be the beginning of my love for western classical music, especially as a result of its many replays, possible for us as a family, thanks to my father who had taken the initiative to audio-record it on our spanking new Hitachi!

(The Navhind Times, Panjim, 22 August 2003)

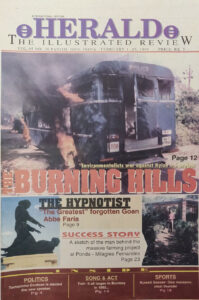

The Hypnotist in Holy Orders

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

Precious little remains till date in the memory of the average Goan. There is a statue of him in the capital city and a street takes his name in Margão. He has been forgotten in his native village of Candolim; only a primary school is named after him there and in some other villages too. He is almost unknown where he worked and lived – Lisbon, Paris and Marseilles. Only an obscure street is named after him in Marseilles.

People may not be apt to remember somebody who lived two centuries ago and with a mysterious sounding name such as Abbé Faria. But what if he has some original scientific contribution to his credit? Never mind that he was a theorist of hypnotism by suggestion, which has since become a vital aid to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. Very often his name is omitted when the subject comes to the fore. Not even does the Encyclopaedia Britannica refer to him as they do Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) and James Braid (1795-1860), who have only usurped his pride of place.

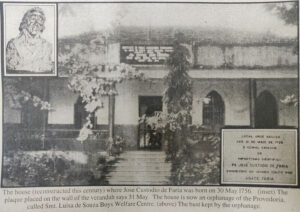

Such has been the fate of José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819), a priest and doctor of theology, who without any medical training did perceive and lend respectability to the true nature of what he called ‘sommeil lucide’ (lucid sleep). It was an intuition characteristic of a true genius. And for this original contribution to the field of science he is regarded at home as the greatest Goan that ever lived.

Early Life

José Custódio de Faria was born on 31 May 1756, to Caetano Vitorino de Faria of Colvale and Rosa Maria de Souza of Candolim. His father was a seminarian and had already received minor orders when he met and married Rosa, the only daughter of a rich landlord of Candolim. He was clever and she was rich, but the combination did not work out that well. Even their son born two years after their marriage, could not prolong their mutual love. Around the year 1764, they got a canonical decree of separation in 1764. He took holy orders and she joined the Santa Monica convent in the  old city of Goa.

old city of Goa.

No bonds linked them ever since. The father and the son stayed a few years at their friends in Candolim – the Pintos of the Conspiracy fame – and at Colvale too. On 21 February 1771, four years after being ordained a priest, Caetano Vitorino left for Lisbon, en route for Rome, to continue his priestly studies. He had similar intentions for his son. Their social circle in Goa and particularly a letter of recommendation they carried for the nuncio in Lisbon, Mgr. Inocencio Conti, won them access to the royal court. Moreover, the reigning monarch, Dom José I, and his prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal, were favourably disposed towards the Goans, whom they strongly recommended for civil, military and ecclesiastical positions at home.

Student in Rome

Thus José Custódio was awarded a scholarship to study in Rome. The father returned to Lisbon in 1777 on attaining a doctorate to further his objective of objective of being appointed the bishop of Goa. His great disappointment and frustration on this count determined much of what followed in his life and his son’s too.

José Custódio stayed on and was ordained on 12 March 1780. At 24 he completed his doctoral thesis titled Theologicae Propositiones: De Existentia Dei, Deo Uno et Divina Revelatione (Theological Propositions on the Existence of God, One God and Divine Revelation) and joined his father in Lisbon.

The duo were good friends but a different purpose animated them. Caetano Vitorino, the more political minded and diplomatic of the two, was fully immersed in matters Goan. He was a sort of self-appointed protector of and influential reference for the Goan community. The Court had been impressed by the fact that, though immensely influential at the highest levels of the kingdom’s administration, he had never asked favours for himself, though it was known that his personal finances were far from bright. But then, intelligence reports began to pin him down as the mastermind and coordinator in Lisbon of a political revolt at home in 1787. As soon as news of this reached Lisbon, they hunted for the duo and their good friends, clerics and laymen.

Meanwhile, all except Fr. Caetano Vitorino had fled to Paris, reportedly to meet and discuss with their envoys of Tipu Sultan, who proposed to be on the French side in their ascendancy against the British in India, but nothing was confirmed in this respect. Others believe that simpler reasons motivated Fr. José Custódio’s sudden departure – that he was attracted by the intellectual climate of France. His father did, however, stay back, still persevering in his designs and probably even overestimating his influence with the high officialdom. He was then put under house arrest in the Carmelite convent where he gave his priestly assistance, and probably died in 1799.

In Paris

Nothing is known of Fr. José Custódio’s activities in the French capital except that he was accused, in 1792, of being a gambler and frequenter of the Palais-Royale. He was acquitted, or at least no action was taken against him by the police. Three years later, on 5 October 1795, he led a battalion of revolutionaries against the National Convention. This political stand made him popular with the supporters of the Directoire and won him the friendship of the Marquis de Chastenet de Puységur.

The latter relationship was decisive. The Marquis had been a disciple of Mesmer whose quackish furrows into ‘animal magnetism’ and tall claims of cures had initially won him the acclaim of high Parisian society. But, in 1785, his exit was shameful. The Marquis, on the other hand, was an honest, well-meaning and cultured person, who took over from where Mesmer had left. Dr Egas Moniz, the Portuguese Nobel Prize Winner and biographer of Fr. José Custódio de Faria, speculates that he acquired knowledge of magnetism in Paris after he struck up an acquaintance with the Marquis.

The first news of Fr. Faria’s activity as a magnetizer is of the year 1802, in the memoirs of Chateaubriand (published in 1843), who referred to his experiments in derogatory terms. He had dined with Fr. Faria at the house of the Marchionesse of Custine. Here, Fr. Faria reportedly declared that he could kill a canary by magnetizing it. However, when the magnetizer was put to the test, he failed, which led Chateaubriand to conclude: ‘O Christian, my presence itself will be enough to make the tripod ineffective!’ Chateaubriand was a devout Catholic. He had strong reservations against magnetism – because of the Church’s attitude of suspicion towards it. But what is more is that Fr. José Custódio de Faria was a Catholic, no less!

Fr. José Custódio continued his research into the subject up to the year 1811, when he was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Marseilles. The Imperial Almanac of 1811 records that he lived there a year and was elected member of a medical society. Since he had no medical qualifications, the membership can only be attributed to his skills as a magnetizer. But for some mysterious reason, he was transferred, in fact, demoted, to the post of auxiliary professor at the Academy of Nimes. He felt slighted and frustrated and, unaccustomed as he was to life in a small city like Nimes, he returned to Paris, in 1813, in search of greener pastures. Unattached to any institution, he initiated his course in magnetism on 11 August 1813, 49, Rue de Clichy.

Sessions

The sessions were held every Thursday, on an admission fee of five francs only. He began with a lecture in halting French. The audience, which consisted largely of women, paid scant attention to this part of the session; their eyes were set on what was to follow – his experiments to substantiate his theory.

Contrary to the claims made by Mesmer, the he could control the body fluids of his patients and rectify their course through special methods invented by him, Fr. José Custódio very humbly put forth that not all individuals could be hypnotised, and that the degree of response to his hypnotic powers necessarily varied from person to person. He was the first to establish that hypnotism was a science of suggestion.

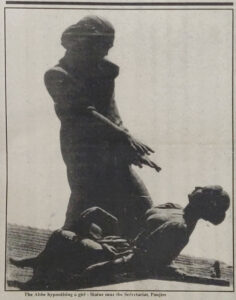

Fr. Faria’s method consisted of a series of well-reasoned and effective actions: he got the patient to sit comfortably and, through concentration, to relax, imagining that they were going to sleep. When the patient was ‘tranquil’, he gave the command, ‘Sleep!’ and, if necessary, repeated it, with a certain degree of urgency, three or four times. If he failed, he would either sportingly give up or try other methods.

The sessions became the rage of the town. There were detractors, critics and skeptics, no doubt. Once, a journalist attended his session and then unjustly criticised and ridiculed the priest in the press. At another session, a leading stage actor, Potier, offered himself for his experiments. He feigned to be in a trance and suddenly rose to say, ‘Ah, Abbé! If you magnetize others as well as you magnetized me, you don’t seem to be doing much.’

Fr. José Custódio put up very well with all such betrayals. He also withstood quite stoically criticism from the clergy and Rome, who then viewed his experiments with suspicion always on the look-out for diabolical influences therein. But the priest always expressed respect for the Church and a firm desire to stay within the Catholic fold. ‘Un esprit supérieur,’ as his disciple Gen. Noizet said of him, he wished to convince the Church that his experiments were fully within the natural realm and that there was no magic or witchcraft involved.

Thus, Fr. Faria took everything in its stride. Only once did he break down, when at Potier’s request the playwright Jules Verne put up a play, on 5 September 1816, the Variétés, titled La Magnétismomanie, ridiculing the Goan priest.

Sad end

The time was now ripe for Fr. Faria to stop his activities. He retired soon thereafter, rendering priestly services in exchange for boarding and lodging.

During the last years of his life, he decided to organize his material in book form. It was an ambitious project in four volumes, of which only the first one is known to have appeared. It is his magnum opus is titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou Étude de la nature de l’homme (On the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study on the Nature of Man). In it he referred to the shameful play:

‘With regard to Magnétismomanie, I cannot ask which laws permit the modern Terence to expose an unknown foreigner to public ridicule. I presume that even the savage would be ashamed to insult his kind, which has nothing in common with actors and the theatre.

‘Far from me the idea to disturb public pleasures: But I might have added to Magnétismomanie a new scene – an extremely pungent one – had my condition not prevented me from doing so, and had my own aversion for such amusements not kept me away from playhouses.’

According to one biographer, by a strange coincidence, the day of his death, also marks the release of his book. His famous words, ‘There are evils that sometimes do good to those who discern their utility,’ might have very well served as his epitaph – if only he had the money for a decent burial. He died at the age of 63, unsung as he was born. A life full of ironies, for born of a rich family he died poor; born of parents who were in love, they separated after his birth; a man with original contributions to posterity, he died with no godfathers to promote his name.

(Herald Illustrated Review, Panjim, Goa. Vol. 95, No. 30, February 1-15 1995. Slightly updated version)