Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

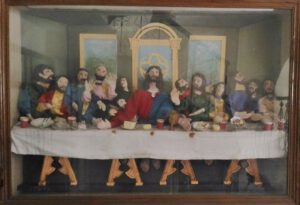

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

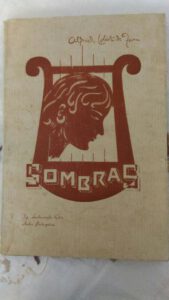

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

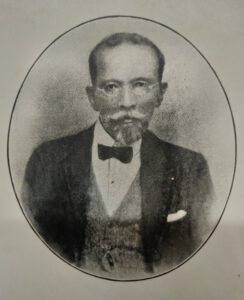

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

A Última Conversa com Percival Noronha

Numa tarde chuvosa (1 de Julho do ano passado), quando de súbito me lembrei do Sr. Percival Noronha[1], não hesitei em terminar a minha sesta dominical. Um distinto cavalheiro – culto, agradável, e que me estimava – daí a dias iria completar a bonita idade de 95 anos… Urgia, pois, falar com o grand old man de Pangim.

Quando liguei para a sua casa, ouvi logo um ‘Estou!’ inconfundível. Na linguagem do Sr. Percival, esse estar era o mesmo que estar disponível! ‘Pode o Óscar vir quando quiser’, disse com a amabilidade que o caracterizava. Estava sempre pronto para um papo, e desta vez seria como nunca dantes: radiodifundida na minha rubrica mensal, Renascença Goa… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRK2PimgTmo) Saí então rumo às Fontaínhas, acompanhado do meu irmão Orlando que trataria das fotos.

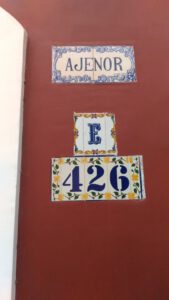

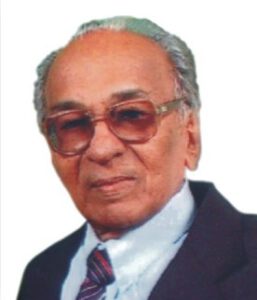

Era um prazer ir à residência do Sr. Percival (‘Ajenor’, nº E-426, à Rua Cunha Gonçalves). Também nos cruzámos, por centenas de vezes, em concertos, conferências, exposições de arte, e não menos em casamentos e funerais. Um senhor da velha guarda, era cumpridor dos seus deveres sociais e cívicos. Apesar da nossa diferença etária, a conversa corria como um rio de águas claras, pois o Sr. Percival era não só envolvente mas também apreciador dos méritos dos seus contemporâneos e estimulador dos talentos dos mais novos.

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Diga-se de passagem que eu admirava o seu automóvel, preto, parecendo sempre novo, tal como o seu proprietário. Este, sempre vestido de bush shirt ou camisa safari, percorria os cantos e recantos da cidade, que conhecia como a palma da sua mão. É que Percival e Pangim se pertenciam um ao outro: foi dos melhores cronistas da capital, do seu ethos e do seu ritmo, que descreveu em bela prosa.[2] E fê-lo com autoridade, mesmo porque presenciou nove décadas, ou seja, metade da história dessa urbanização,[3], de forma que hoje se torna difícil imaginar o nosso Pangim sem o Sr. Percival Noronha.

Cargos oficiais

Feitos os estudos liceais na capital, o Sr. Percival Noronha entrou para a administração pública, em 1947. Trabalhou, primeiro, nas Obras Públicas, passando depois para os Serviços da Estatística e Informação. Quando esta foi desagregada, o distinto professor e escritor António dos Mártires Lopes levou-o consigo para os novos Serviços de Turismo e Informação de que este acabava de ser nomeado chefe. O Sr. Percival nunca se esqueceu dos belos tempos do Liceu e do funcionalismo que passou sob a alçada directa desse seu antigo professor liceal: confessava que essa relação fora fundamental em nutrir a sua paixão pela história e cultura.

Quando se deu a mudança do regime politico, em Dezembro de 1961, o Sr. Percival era chefe-adjunto dos Serviços da Informação, reportando ao governador-geral Vassalo e Silva. Em Junho de 1980, a visita do simpático governador coincidiu com as comemorações do 4.º centenário da morte de Luís de Camões em Goa. Vinha a título pessoal, mas nem por isso a visita deixou de suscitar controvérsia.

Decorreu-se o pior da cena no Azad Maidan (‘Largo da Liberdade’), a antiga Praça Afonso de Albuquerque. Aqui, à certa distância, vi o antigo governante a ser interpelado por alegados actos de comissão e omissão do regime português em Goa.[4] O embaraçoso incidente atalhou-o o Sr. Percival Noronha, que, na qualidade de chefe de Protocolo do Território de Goa,[5] estava incumbido de acompanhar o ilustre visitante.

Antes dessa data, com a limitada bagagem de conhecimentos de inglês auferidos no Liceu, e língua essa que logo veio a dominar, o Sr. Percival Noronha ocupou outros cargos importantes na administração indiana. Foi sub-secretário das indústrias, minas, trabalho, saúde e turismo. Entre muitas outras iniciativas suas, os hospitais do Asilo em Mapuçá e o Hospício de Margão passaram a subordinar-se à Direcção de Saúde. Desenvolveu as zonas de Calangute, Colvá, Mayém e Farmagudi, e ideou os desfiles do Carnaval e Xigmó; teve papel preponderante no arruamento Campal-Miramar e na arborização do Parque Infantil; e foi um dos responsáveis pela realização da grande Feira Agrícola em 1970. Ora, possuidor dum raro espírito de autocrítica, não ocultava as faltas que houvera no planeamento e execução dessas suas propostas.

Não admira que o Sr. Percival Noronha tivesse sido um solteirão muito cobiçado. Passou, porém, a vida a cuidar da veneranda mãe, vindo a aposentar-se apenas um ano após a sua morte. Era igualmente dedicado à vida burocrática, passando horas a fio à mesa do gabinete, até para além das horas regulamentares. Um funcionário desse quilate podia facilmente esquecer-se de si próprio, como foi, na verdade, o caso do Sr. Percival Noronha.

Vida de aposentado

Teria sido diferente a sua vida depois de aposentado em 1981? Mudou de actividade, sim, mas o expediente não mudou de volume. Dedicou-se, a tempo inteiro, às matérias por que tinha propensão natural: a arte, a história e a astronomia.

Começou por dotar a sua residência com mobiliário de estilo tipicamente indo-português. Efectuou-se grande parte dessa obra no rés-do-chão do seu prédio, o qual havia sido confiado ao conhecido carpinteiro Zó. Disse-me, em mais de uma ocasião, que gastara nisso quase todas as suas economias. Também é verdade que todo dinheiro lhe era pouco quanto se tratasse de comprar objectos de arte e livros.[6] Assim, a casa se viu transformada em verdadeiro museu-arquivo que deveras honra o histórico bairro das Fontaínhas.

O Sr. Percival não parou por aí: tomou a peito vários assuntos de interesse público. Inspirado pelo alto funcionário (e depois governador) K. T. Satarawala, no ano de 1982 abriu um ramo da Indian Heritage Society em Goa e foi professor convidado da Faculdade de Arquitectura. Exerceu o cargo de secretário daquela organização não-governamental que, em colaboração com a Town and Country Planning Department, preparou um relatório sobre os prédios e sítios de importância arquitectónica no território de Goa. Foi também tesoureiro do INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) em Goa.

Esses organismos continua a desempen har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

Embora o Sr. Percival Noronha fosse indiferente em matéria religiosa, nunca hostilizou a Igreja. Pelo contrário, reconhecendo o papel desta no progresso espiritual e material dos povos, colaborou com as entidades eclesiásticas. Em 1986, quando da visita do Papa João Paulo II, participou entusiasticamente na preparação do evento. E, em 1994, foi membro fundador do Museu de Arte Cristã que ora se acha no Convento de S. Mónica.

Esse goês de gema era um arco-íris de saberes, tratando tanto da arqueologia como da astronomia com a mesma facilidade. Fundou a Association of Friends of Astronomy (AFA)[10], em 1982. Este organismo, além de vir a publicar uma revista mensal, Via Lactea, editada pelo fundador, abriu, em 1990, um observatório astronómico público – o primeiro do seu género na Índia – com o apoio do Departamento de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio-Ambiente, do Estado de Goa.

O Sr. Percival Noronha viveu uma vida sem artifícios – plain living and high thinking. Foi um líder cultural que criou à sua volta uma pleiade de jovens com decidida propensão pela história, arqueologia, arte e astronomia. Na sua casa, onde funcionavam os dois organismos que criou, recebia jornalistas, pesquisadores e outra gente interessada. Teimava em alertar a geração nova sobre o grave estado de bancarrota civilizacional em que a sua amada Goa estava a descambar. Esses recursos humanos e hábitos salutares sendo o maior legado do Sr. Percival Noronha, tem razão a Fundação Oriente em apelidá-lo de “Um Goês Exemplar”, num livro que publicou em sua homenagem.

Na verdade, é a vida intelectual que o entusiasmava, contribuíndo também para a sua saúde física. A sua roda de amigos da velha data[11] nutria a saudade pelo passado enquanto a geração nova o desafiava com projectos futuristas. Era um desses amicus certus, que tratando-se de algum sem-vergonha, falava, tipicamente, com ironia e sorriso escarninho. Mas não vou sem frizar que a todos desejava o bem, e para uma vida saudável recomendava-lhes uma medida de moog grelado por dia! Antes da prótese da anca, em Abril deste ano, esteve relativamente lúcido e ágil.

Última conversa

96 anos da vida. Dir-se-ia mesmo que o Sr. Percival Noronha teve sete vidas. Nos últimos anos era seu costume, quando adoecesse, anunciar a sua morte e daí a dias estar em pé! Era como que tivesse um sistema imunológico como o do gato persa, de que gostava. Não era motivo para recear, pois, quando ouvi de novo que o Amigo estava em declínio. Tive, porém, empenho em conversar com ele demoradamente.

Às 4,30 da tarde, o Sr. Percival tinha já à mesa o bule de chá e bolachas. Dormira a sesta e estava pronto para uma conversa. A rapariga, às ordens, sentada lá no fundo da sala. E parecia tudo como dantes...

Foi quando notei que o venerando ancião tinha o cabelo despenteado, a barba por fazer, e faltava-lhe a placa de dentes. Nunca o vira assim… Os apetrechos de trabalho estavam lá todos, arrumadinhos, nas estantes e armários, dum lado da sala de jantar, onde costumava passar grande parte do tempo a trabalhar. Também isso não estava como dantes... E reflecti também que desta vez o meu anfitrião que viera ele à janela, como era seu costume, deitando para mim a chave da porta principal… Tudo isso indicava que a sua vida ia afrouxando. Fiquei triste.

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

No entanto, ia falando sobre o seu currículo escolar e profissional; as suas actividades depois de aposentado; sobre Salazar (cuja inteligência e honestidade admirava) e o 18/19 de Dezembro; a administração, portuguesa e indiana; os cursos e conferências que realizou nas universidades da Ásia e Europa; o futura da língua portuguesa em Goa; a cultura goesa e a distorção da sua história; os seus amigos e as pessoas que admirava; e a vida em Pangim: tudo isso, entre muitos outros assuntos, e não necessariamente nessa ordem de ideias.

Nos últimos meses, vi-o, várias vezes, debruçado no peitoril da varanda, qual abencerragem a observar a vida que corria lá fora, e com a cara de quem pensa: Quantum mutatis ab illo… Barbudo, lembrava Abraão, personagem de primordial importância para as comunidades à sua volta. E com aquele cabelo a voar e ele a fitar o firmamento, assemelhava-se à figura de Einstein…

Também lá do alto do Céu ouvirá – no último domingo do mês de Novembro deste ano – a última entrevista que concedeu cá na terra. Foi a minha última conversa com o Sr. Percival Noronha.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] De nome completo, Percival Ivo Vital e Noronha (26.7.1923 –19.8.2019), filho de António José de Noronha, de Loutulim, e de Aurora Vital, de S. Matias.

[2] “Panjim: Princess of the Mandovi” (2002); “Fontaínhas: vivendo com o passado”(2001); “Fontaínhas: the Tale of Panjim’s Latin Quarter” (2003), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015)

[3] A vila de Pangim foi elevada à cidade com a denominação de Nova Goa, por alvará de 22 de Março de 1843, o qual lhe outorgou todos os privilégios de que gozavam as cidades de Portugal Continental.

[4] O incidente impulsionou a minha primeira intervenção jornalística em forma de uma carta ao director dum jornal de Pangim – “Our Honoured Guest”, in The Navhind Times, 12/6/1980.

[5] Na altura, cumulava este cargo com o de director da administração das Obras Públicas.

[6] Doou a sua casa ao sobrinho Francisco Lume Pereira, de Verna, onde Percíval Noronha faleceu, e os livros doou-os à Universidade dos Açores e à Krishnadas Shama Library, de Pangim; e os diapositivos, ao Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino.

[7] “Christian Art in Goa” (1993); “Indo-Portuguese Furniture and its Evolution” (2000); “Priceless Christian Art” (2004), e “Goan Artisans” (2008), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[8] “Levantamento arqueológico da Velha Goa e tentativas para a sua conservação” (1989); “Old Goa in the context of Indian heritage”(1997); “Um passeio pela Velha Cidade de Goa”(1999); “A Capela de Nossa Senhora do Monte, em Velha Goa” (2001), ), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[9] Recebeu ao todo 16 galardões de proveniência vária.

[10] http://afagoa.org/about_us.html

[11] Entre outros, António dos Mártires Lopes, Aleixo Manuel da Costa, Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes, Alcina dos Mártires Lopes, Artur Teodoro de Matos, Luís Filipe Thomaz, Teotónio de Souza, Rafael Viegas, Nandakumar Kamat, Satish Naik.

[12] Tradition and Modernity in Eighteenth-Century Goa (Manohar, New Delhi & Centro de HIstória de Além-Mar, Lisboa, 2006)

[13] Old Goa: A Complete Guide (Panjim: Third Millennium, 2004)

[14] Castilho de Noronha: por Deus e pelo País (Panjim, Third Millennium, 2018)

Fotos de Orlando de Noronha, com excepção da da condecoração (e-cultura.pt) e da do lançamento do livro (Fundação Oriente)

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série, Número 1, Maio/Dezembro de 2019 https://issuu.com/jmm47/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n1_-_maio-dez_

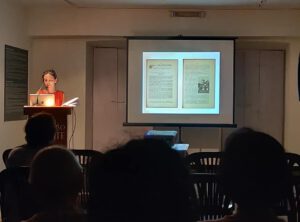

All about Amor

Maria do Carmo Piçarra’s talk at Fundação Oriente, Panjim, was titled “Behind the Portrait of Antunes Amor, Educator and Pioneer of Cinema in Goa”. A researcher at Instituto de Comunicação da Nova (ICNOVA), Lisbon; assistant professor at University of the Arts, London (UAL); and a Fundação Oriente scholar, Piçarra holds a doctorate in Communication Sciences. She is a film programmer; author of several publications, among them Azuis Ultramarinos. Propaganda colonial e censura no cinema do Estado Novo (2015) and Salazar vai ao cinema (2006, 2011), and principal editor of (Re)Imagining African Independence. Film, Visual Arts and the Fall of the Portuguese Empire (2017).

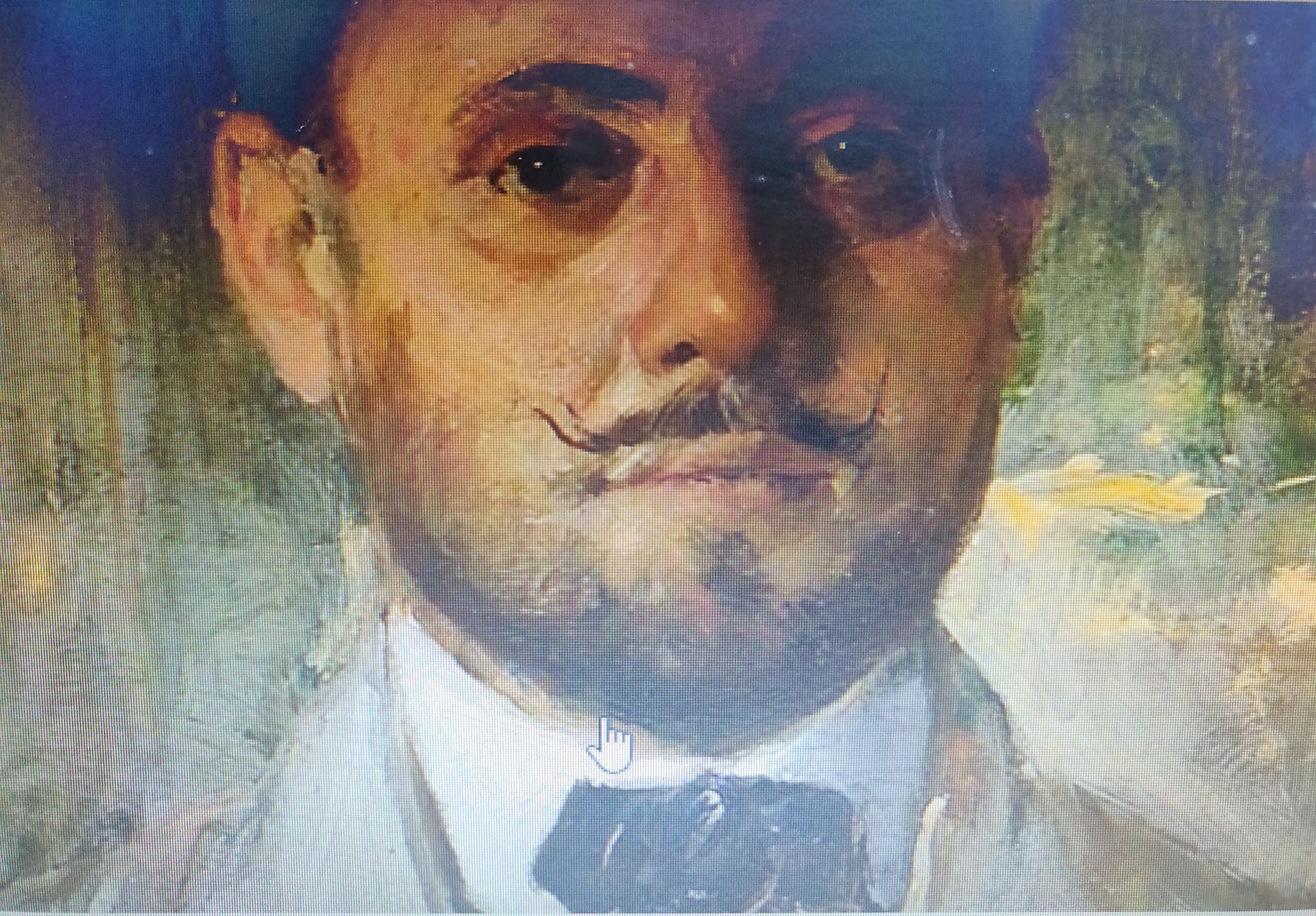

Piçarra contextualised a painting titled “Mr. Amor. The Portuguese Agent” (1917) from the Trindade Collection on permanent display. That striking piece of art by the Bombay-based Goan painter António Xavier Trindade (1870-1935) was gifted to the Foundation by Dr Marcella Sirhandi, a friend and biographer of the artist.

Piçarra spoke of Amor’s cinematographic forays in Macau, where he screened his first amateur movie. She also mentioned the films he made about school life, history, and so on, while in Goa. A strong defender of the pedagogical and propagandist uses of cinema, Amor had several of his films shown in local halls.

The precious little I already knew of Manuel Antunes Amor (1881-1940) I had heard from my father a quarter of a century ago; I was now surprised to see him again! Trained in Germany in the early twentieth century, Amor (‘Love’, in Portuguese) was a self-opinionated gentleman whose tenures as primary school inspector in Goa (1916, 1922) were mired in controversy.

Finally, Piçarra's remark that Amor was particularly suspicious of lawyers reminded me of that high-profile polemic he had with Joaquim de Araújo Mascarenhas (1886-1946), a Goan legal eagle who doubled as Portuguese language teacher at Liceu Nacional de Nova Goa. A lethal combination it proved to be.

An article titled “O ensino primário e a incúria do Estado” ('Primary school education and State neglect') that Araújo Mascarenhas wrote for the maiden issue of the monthly Boletim de Educação e Ensino (April 1927) made Amor see red. He wrote a censorious rejoinder, “Sem autoridade nem razão” ('Devoid of authority or reason'), in the very next edition.

Araújo Mascarenhas dashed off a point-by-point rebuttal. The Boletim’s editorial board that comprised primary school teachers declined to publish it, possibly fearing the inspector's wrath. It led the redoubtable polemist to bring out a volume titled Resposta a uma provocação ('In Response to a Provocation').

Sadly, the Boletim folded up in August that year, but not before the long series of events had vitiated the atmosphere. No wonder the very gifted Mr Amor was someone many Goans loved to hate.

Dr Adélia Costa: Goa's angel of mental health

She was Goa’s best known neuropsychiatrist. The first to turn the spotlight on mental health in our land, she served the community professionally for half a century. She now lives a quiet retired life amidst close family in Miramar.

Few would know that Maria Adélia Peres e Costa, who turns 90 today, is Goa’s first neuropsychiatrist. After graduating from the Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa, she pursued specialised studies in Lisbon, becoming the first lady neurologist in Portuguese territory. On her return to Goa in 1958, she was appointed the first director of the freshly set up state-run Abade Faria hospital, now Institute of Psychiatry and Human Behaviour.

A research paper in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry states that the young director was appalled at antiquated methods of handling lunatics and bizarre practices of interning political prisoners alongside those patients! She highlighted the anomalies and suggested corrective measures, in a report that the Portuguese local government promptly accepted. At once deputed to source modern equipment and medicines from France, she returned with many goodies for the so-called “children of a lesser god”.

They eagerly waited to meet that doctor who spoke little but did a lot, that healer whose initial reserve quickly gave way to a smile and some curative banter.

Brand-new infrastructure alone can do no wonders, much less do away with stigma attached to a mental hospital. So it was the range of humane practices inspired by Dr Adélia that finally led to an attitudinal change in the staff and the public. Patients were brought out from custody to an open and friendly environment. The hospital staff became skilled at grooming the inmates and administering standard medications. Relatives and friends, too, eventually began to minister to their kin with tender love and care. A gentle revolution in healthcare got started.

By March 1962, however, Dr Adélia had sensed that the gentle revolution would not be sustainable. The resolute lady was on her final round of the hospital wards while, thousands of miles away, Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest exposing Nurse Ratched’s antics in an Oregon psychiatric hospital, was making waves for all the right reasons.

Meanwhile, Dr Adélia flew out to Portugal, this time to study psychiatry, and on her return set up private practice in Panjim. Before long, Dr Adélia became a household name, a name synonymous with mental health. Her residence and clinic was always teeming with patients, many of them from beyond the borders of Goa. They eagerly waited to meet that doctor who spoke little but did a lot, that healer whose initial reserve quickly gave way to a smile and some curative banter. Never mind the labels “nervanchi dotor” and “pixianchi dotor” contrived by the man in the street, medical cases were sure to find ethical solutions at the hands of this angel of mental health.

Dr Adélia had the makings of a model physician. Not only was she on top of the latest news and trends in medicine, she worked tirelessly, disregarding her personal ups and downs. That she could recall case histories with ease spoke volumes about her commitment. A cool head, a good listener, she was empathetic to the mental and material needs of the patients, and they never felt rushed. Even as it was striking that she always put on the white coat, it was even more so that she meticulously filed her patient treatment cards to the very end. She exuded self-confidence, yet humility was her abiding trait. And all of this came from her passion to make a difference in the lives of others.

There was an obvious connection between Dr Adélia’s faith and her life as a medico. She has been a contemplative in action

In addition to being a remarkable professional, Dr Adélia is a remarkable senhora. While fully dedicated to her clinical responsibilities, she also saw to her other obligations. After a hard week’s toil she would drive down to Loutulim in her Fiat and, later, a first-generation Maruti-Suzuki (both in classy shades of green) to spend weekends with her mother. And amidst all the chores, she still found the time to read and have a chat. And yes, she stopped to pray. She was more than just a Sunday Catholic. Her participation in the early morning Way of the Cross at the city church on Good Friday is one picture that has stayed with me since I first saw it.

There was an obvious connection between Dr Adélia’s faith and her life as a medico. She has been a contemplative in action, living out beautifully what the twentieth-century savant Alexis Carrel called “a journey of the soul towards the realm of grace.” May that marvellous cycle live on. A role model for many, Dr Adélia has spent an entire lifetime alleviating human suffering, by treating and reassuring others. She can feel blessed with the assurance that she lives in their grateful hearts and minds.

(An abridged version of this article was published in The Goan, Panjim, 27 August 2018)

http://epaper.thegoan.net/1792134/The-Goan-Everyday/The-Goan-Everyday#page/4/1

Remembering Prima Maria

November 1987. I was all of twenty-two years old and had landed in Lisbon. Shortly after this I phoned a relative for whom I’d carried a little parcel from her sister Genoveva (to whom I became a sobrinho by marriage but remained first a primo, via Curtorim). Her name was Rita Maria Gomes. I’d never met her before; yet she sounded so warm that I promptly accepted her lunch invitation. Her brother Nicolau stopped over to collect the item, early the next morning, shaking me out of my jet lag: he was my only visitor at Hotel Berna, Campo Pequeno, where I’d put up in the first three days of my year-long stay in Portugal.

After my maiden Sunday Mass na terra de Camões, I headed for Carcavelos, half an hour’s journey by train from Cais do Sodré. Usually shy at a first meeting, I was nonetheless eager to see my mother Judite’s “Guirdolim cousins”.

At Oeiras, on a near-empty platform, Primo Amâncio Frias Pinto and I easily spotted each other. As he comfortably drove me home in his white Renault 10, his down-to-earth style put me at ease. And then, when Prima Maria and the family welcomed me, I noticed the glow on her face: she had taken a shine to Judite’s son. My gracious hostess had very thoughtfully invited three primos still new to me: Noémia and her children Lena and Stuart. I instantly identified the senior one (now a much-loved Tia) as daughter of Primo ‘Picu’ Stuart, who I’d been very fond of as a child… Now here was a heady mix of Neurá and Curtorim/Guirdolim, and it made my day!

I have no photographs of that memorable coming together. That was altogether another age, the pre-digital age! I vividly remember, however, that the apartment was bathed in sunlight. Prima Maria had the table laid de rigueur and served a full course meal. It wasn’t easy, but she did it! And, yes, she kept up an animated conversation, centred on Goa, our relatives and friends.

It was still a bright and pleasant afternoon when Prima Maria suggested we take a stroll in the colourful feira nearby. And soon it began to feel like home. When evening came and Primo Amâncio (who’d been my father Fernando’s contemporary at Casa de Estudantes) dropped me off to the station, I felt a sudden pang of saudade…

..........................................................................

August 2018. Years after my unforgettable passage to Portugal, I met the simpático casal at their ancestral house at Ararim, Socorro – which, meanwhile, I’d become familiar with as the home of my wife Isabel’s maternal aunt Bernadete married to Terêncio Frias Pinto. Prima Maria made a few more trips to Goa, travelling solo after her husband’s demise. Last year, we crossed paths at Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church. That’s when I quickly fixed up a lunch appointment; and unable to meet up at home, we decided on a thali at the Fidalgo.

How can we forget the people who’ve made us happy at some time or other in our lives? I’m glad I started off by recalling the lovely moments spent with her family – oh my God! – three decades ago...

As for her, she was soaked in memories. She smiled wistfully, reminiscing about her spinster days in Goa and as a young wife in Mozambique, and gave me the lowdown on her life as a widow.

A grandmother of two, pretty even at eighty, Prima Maria was proud of her Gomes ancestors who made it big in Portugal. She spoke ardently about the Veiga-Gomes kinship, and – surprise of surprises – she pulled a neat set of notes and sepia out from her handbag to confirm that the doctor-politician Pestaninho da Veiga (1849-1901), the physician-writer A. X. Heráclito Gomes (1864-1934), and the poet Mariano Gracias (1871-1931), who died in Lisbon, were indeed first cousins! Prima Maria was thus a third cousin of my mother’s; her children Rui and Lara, and I, sit a step below.

Needless to say, formal relationships are not everything; it’s the level of friendship that counts. For instance, when the infant Maria Rita da Veiga, died of bronchopneumonia, a day prior to the arrival of a baby in the Gomes household, this new-born was baptised Rita Maria. The noble gesture speaks volumes of the oneness of spirit that proceeds from life built around shared values! In any case, a rarity in our day and age, this episode endeared the new Maria very especially to my mother who, aged 3½ years, had been confused and shaken by the disappearance of her immediate junior sibling.

There are, on the other hand, myriad incidents over which one has no control whatsoever; one gets to join the dots only much later. Consider my mother’s passing, at the age of 83½ years, precisely on Rita Maria’s eightieth birthday! Doesn’t this say something about the communion of saints that often goes unnoticed even by practising Catholics?

Life never ceases to amaze us. Prima Maria, despite her aches and pains, travelled to Canada, New Zealand and Australia – aching to connect with friends and relatives – whereas I’d failed to get in touch with her brother Heráclito in Porto. I’d thought of him, even in the midst of São João celebrations there, but it had remained just that – a thought… That I finally got to meet him, thirty years later, on Facebook, is another matter entirely! We now stand in awe of this gift from cyberspace.

My first – and last – lunch invitation to Prima Maria inevitably ended, but not before my mobile phone camera – sensing our connectedness – clicked away, trying to discover facial resemblances between kith and kin… And it was saudade once more…

Still a sunny afternoon, much like the one at Carcavelos, I drove Prima Maria to ‘A Pousada’, a pensão she was staying at, in the city’s charming São Tomé ward. We said our goodbyes, and I left. When I called up after a month, I got no answer… Heaven knows why!

Até sempre, Prima Maria!

Papa - 1

Fernando do Carmo Heitor de Noronha, filho primogénito de Tomaz Nuno Francisco Carmo de Noronha, de Neurá-o-Grande, e Leonor Zoraide do Rosário e Sousa, de Aldonã, nasceu em casa dos avós maternos. Casado com Judite Teresa da Veiga, de Curtorim, tinha o Curso Complementar dos Liceus (de Letras e de Ciências).

Funcionário público (do Quadro da Administração Civil e, mais tarde, do da Polícia Judiciária), depois de aposentado, nos anos 70, esteve ligado a O Heraldo, o último diário da língua portuguesa em Goa, fundando depois, com outros, em 1983, o semanário A Voz de Goa, que veio a ser o último periódico expresso no idioma luso. Dedicado à língua portuguesa, entre os anos 1985-88, foi professor-convidado de Português no Xavier Centre of Historical Research (Miramar/Porvorim) e no Dhempe College of Arts & Science, Miramar.

Em 2002, publicou o seu primeiro livro, Momentos do meu Passado, sob a chancela da casa editora Third Millennium, fundada pela família e de que era parceiro, sendo talvez a única casa a publicar livros em português nesta parte do mundo. Um segundo volume de memórias – Goa tal como a conheci – será lançado dentro de meses. E ainda tem vários inéditos.

Era pai/sogro de Óscar/Isabel, Ilídio/Imelda, Ivo/Tânia, Sávio/Olívia e Orlando/Tina, e avô de quinze netos (7 rapazes e 8 raparigas).

(Apontamentos prestados à Revista Ecos do Oriente, de Loures, Portugal, cujo director, Mário Cirilo Viegas, publicou, com acrescentamentos que não estão integrados no presente texto, sob o título de ‘Fernando de Noronha: Um Indo-Português de Caráter’, na edição de Jul-Set de 2011 (Ano VI, N.º 23), com capa e editorial dedicados a meu Pai)

Magic Aunt Zita

When our best-loved aunt Zita left for her heavenly abode a year ago, we felt a light going out of our lives. There was darkness everywhere. She had been struck by a crippling illness for a considerable period, but magically, her own light never flickered; on the contrary, by her exemplary fortitude, she radiated still more light. I got the picture when I spent a day by her side, at her home in Curtorim, to recall the good old times and to especially thank her for all that she meant to us. In her last months, kith and kin she had not seen in a long time also had the fortune of meeting up with her.

Tia Zita spelt magic, in the positive sense of the term. She was cheery – that’s magic; she loved unconditionally – and that’s magic, too. What else could one wish for? You ask, what is the secret of all this? Her very life – lived less for self and more for others. Her unspoken motto was ‘Fazer o bem, sem ver a quem’: Doing good to all and sundry. At times she must have felt misunderstood, but she took it all in her stride, convinced that loving kindness conquers all!

St Paul exhorted the New Christians to be, ‘like Christ, everything to everybody’. To some our aunt was the Sun, to others the Moon. She burnt strong and bright as the sun, and stood by her family like a rock; and like the moon, her soft side provided a cushion to the family’s generation-next in their difficult moments. She would make light of any problem and top it off with a delectable treat!

With that perfect balance she managed home and office. Her husband experienced her self-giving love for more than quarter of a century; colleagues at office and staff at home valued her understanding and jovial disposition. She generously gave of her time, especially to her mother, and of her money to those in need. Her easy smile would turn into peals of laughter, triggered by an upfront comment or some naïveté of yesteryear. With no children of her own, she was a mother to her nephews and nieces. It was in her nature to reach out to everyone, which won her the epithet ‘Mother of Mercy’!

She was a woman ahead of her times. She studied and worked in British India and then joined the state tourism and information bureau in the Goan capital. In the early 1970s – when hardly any lady in Goa dreamed of owning a two-wheeled motor vehicle – she would ride her Rajdoot scooter to her workplace in Margão. This spoke of her outgoing personality, her initiative, and of her daring, too, especially considering that she could neither start the bike nor park it securely: a man-servant at home and a peon at the office usually did the honours!

As the first manager of the government-owned tourist cottages in Farmagudi, she once played host to our bachelor statesman Vajpayee, then a foreign minister. He praised her penchant for landscaping, while our aunt quite naturally engaged in repartee reflecting the Goan joie de vivre. All of which must have got our poet-minister to pen a verse or two!

Aunt Zita herself was not an armchair tourist; impelled by the travel bug, that slim and fair-skinned lady, who was always in step with fashion, crisscrossed India and some countries in Europe, with a relative or a friend. And after having been a ‘tourist’ all her life, in the two decades of her retirement she was essentially a ‘pilgrim’ who daily went to church for Mass and was engaged in charitable activity.

Several years earlier, a critical tryst with illness, which she was healed of thanks to a non-surgical intervention by the saintly Dr Ernest Borges, had been a turning point in her life. But her final test came during the Holy Week last year: she lay in the hospital bed – her purgatory on earth – her sweet visage reflecting Christian resignation vis-à-vis that inescapable moment of reckoning.

It is a moral certainty that Tia Zita is now in the Beatific Vision. And most certainly, too, none of what has been said here will be of importance to her; it rather will make us all the difference to realize that her life was an echo of this touching quote: ‘I shall pass through this world but once. Any good therefore that I can do or any kindness that I can show to any human being, let me do it now. Let me not defer it or neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again’ – which could well be a way for us – who are not of this world – to look forward to the treasure that awaits us in Heaven.

(Herald, 27 March 2009)

Banner pic: Isabel and I, flanked by T. Zita and T. Francisquinho, Neura, 13 May 1994

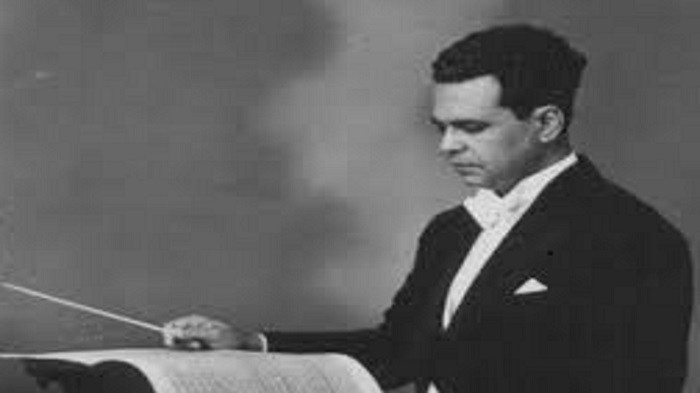

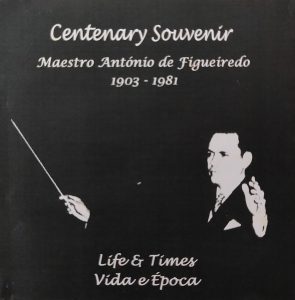

THE MAESTRO’S TOUCH

Three cheers to the first of our very own Von Trapps – on their comeback and creditable stage performance during the birth centenary celebrations of their patriarch António de Figueiredo. This Goan maestro was perhaps singly responsible for setting the Western musical scene in our land on a firm professional footing, way back in the mid-1950s. I heard he was quite a sensation in those days and exerted an important influence on the Goan people.

I heard he was quite a sensation in those days and exerted an important influence on the Goan people.

I vividly remember my parents recommending the Goa Philharmonic Choir and Symphony Orchestra, which was to perform under his baton at the Menezes Braganza hall, in 1973. It was a veritable feast for my senses as an eight year old, never mind the minimal acoustic conditions of the venue. The concert also proved to be the beginning of my love for western classical music, especially as a result of its many replays, possible for us as a family, thanks to my father who had taken the initiative to audio-record it on our spanking new Hitachi!

How I wish the local stations of All India Radio and Doordarshan had taped the proceedings of this birth centenary for the larger Goan family at home and abroad! And as a more eloquent public homage to the maestro, it would in the fitness of things to have Kala Academy’s open-air auditorium named after him who was the founder-director of the Academia de Música (now Kala Academy’s department of Western Music), and similarly, a prominent city and village street too; to have a bust of the maestro installed in the premises of the Kala Academy, scholarships instituted in his memory, and to entrust a musicologist with the job of writing a biography and putting together his musical works. The centenary CD released by his admirers is a step in the right direction, but only for starters!

How I wish the local stations of All India Radio and Doordarshan had taped the proceedings of this birth centenary for the larger Goan family at home and abroad! And as a more eloquent public homage to the maestro, it would in the fitness of things to have Kala Academy’s open-air auditorium named after him who was the founder-director of the Academia de Música (now Kala Academy’s department of Western Music), and similarly, a prominent city and village street too; to have a bust of the maestro installed in the premises of the Kala Academy, scholarships instituted in his memory, and to entrust a musicologist with the job of writing a biography and putting together his musical works. The centenary CD released by his admirers is a step in the right direction, but only for starters!

The concert also proved to be the beginning of my love for western classical music, especially as a result of its many replays, possible for us as a family, thanks to my father who had taken the initiative to audio-record it on our spanking new Hitachi!

(The Navhind Times, Panjim, 22 August 2003)

The Hypnotist in Holy Orders

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

Precious little remains till date in the memory of the average Goan. There is a statue of him in the capital city and a street takes his name in Margão. He has been forgotten in his native village of Candolim; only a primary school is named after him there and in some other villages too. He is almost unknown where he worked and lived – Lisbon, Paris and Marseilles. Only an obscure street is named after him in Marseilles.

People may not be apt to remember somebody who lived two centuries ago and with a mysterious sounding name such as Abbé Faria. But what if he has some original scientific contribution to his credit? Never mind that he was a theorist of hypnotism by suggestion, which has since become a vital aid to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. Very often his name is omitted when the subject comes to the fore. Not even does the Encyclopaedia Britannica refer to him as they do Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) and James Braid (1795-1860), who have only usurped his pride of place.

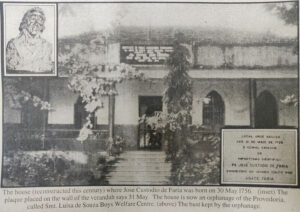

Such has been the fate of José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819), a priest and doctor of theology, who without any medical training did perceive and lend respectability to the true nature of what he called ‘sommeil lucide’ (lucid sleep). It was an intuition characteristic of a true genius. And for this original contribution to the field of science he is regarded at home as the greatest Goan that ever lived.

Early Life

José Custódio de Faria was born on 31 May 1756, to Caetano Vitorino de Faria of Colvale and Rosa Maria de Souza of Candolim. His father was a seminarian and had already received minor orders when he met and married Rosa, the only daughter of a rich landlord of Candolim. He was clever and she was rich, but the combination did not work out that well. Even their son born two years after their marriage, could not prolong their mutual love. Around the year 1764, they got a canonical decree of separation in 1764. He took holy orders and she joined the Santa Monica convent in the  old city of Goa.

old city of Goa.

No bonds linked them ever since. The father and the son stayed a few years at their friends in Candolim – the Pintos of the Conspiracy fame – and at Colvale too. On 21 February 1771, four years after being ordained a priest, Caetano Vitorino left for Lisbon, en route for Rome, to continue his priestly studies. He had similar intentions for his son. Their social circle in Goa and particularly a letter of recommendation they carried for the nuncio in Lisbon, Mgr. Inocencio Conti, won them access to the royal court. Moreover, the reigning monarch, Dom José I, and his prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal, were favourably disposed towards the Goans, whom they strongly recommended for civil, military and ecclesiastical positions at home.

Student in Rome

Thus José Custódio was awarded a scholarship to study in Rome. The father returned to Lisbon in 1777 on attaining a doctorate to further his objective of objective of being appointed the bishop of Goa. His great disappointment and frustration on this count determined much of what followed in his life and his son’s too.

José Custódio stayed on and was ordained on 12 March 1780. At 24 he completed his doctoral thesis titled Theologicae Propositiones: De Existentia Dei, Deo Uno et Divina Revelatione (Theological Propositions on the Existence of God, One God and Divine Revelation) and joined his father in Lisbon.

The duo were good friends but a different purpose animated them. Caetano Vitorino, the more political minded and diplomatic of the two, was fully immersed in matters Goan. He was a sort of self-appointed protector of and influential reference for the Goan community. The Court had been impressed by the fact that, though immensely influential at the highest levels of the kingdom’s administration, he had never asked favours for himself, though it was known that his personal finances were far from bright. But then, intelligence reports began to pin him down as the mastermind and coordinator in Lisbon of a political revolt at home in 1787. As soon as news of this reached Lisbon, they hunted for the duo and their good friends, clerics and laymen.

Meanwhile, all except Fr. Caetano Vitorino had fled to Paris, reportedly to meet and discuss with their envoys of Tipu Sultan, who proposed to be on the French side in their ascendancy against the British in India, but nothing was confirmed in this respect. Others believe that simpler reasons motivated Fr. José Custódio’s sudden departure – that he was attracted by the intellectual climate of France. His father did, however, stay back, still persevering in his designs and probably even overestimating his influence with the high officialdom. He was then put under house arrest in the Carmelite convent where he gave his priestly assistance, and probably died in 1799.

In Paris

Nothing is known of Fr. José Custódio’s activities in the French capital except that he was accused, in 1792, of being a gambler and frequenter of the Palais-Royale. He was acquitted, or at least no action was taken against him by the police. Three years later, on 5 October 1795, he led a battalion of revolutionaries against the National Convention. This political stand made him popular with the supporters of the Directoire and won him the friendship of the Marquis de Chastenet de Puységur.

The latter relationship was decisive. The Marquis had been a disciple of Mesmer whose quackish furrows into ‘animal magnetism’ and tall claims of cures had initially won him the acclaim of high Parisian society. But, in 1785, his exit was shameful. The Marquis, on the other hand, was an honest, well-meaning and cultured person, who took over from where Mesmer had left. Dr Egas Moniz, the Portuguese Nobel Prize Winner and biographer of Fr. José Custódio de Faria, speculates that he acquired knowledge of magnetism in Paris after he struck up an acquaintance with the Marquis.

The first news of Fr. Faria’s activity as a magnetizer is of the year 1802, in the memoirs of Chateaubriand (published in 1843), who referred to his experiments in derogatory terms. He had dined with Fr. Faria at the house of the Marchionesse of Custine. Here, Fr. Faria reportedly declared that he could kill a canary by magnetizing it. However, when the magnetizer was put to the test, he failed, which led Chateaubriand to conclude: ‘O Christian, my presence itself will be enough to make the tripod ineffective!’ Chateaubriand was a devout Catholic. He had strong reservations against magnetism – because of the Church’s attitude of suspicion towards it. But what is more is that Fr. José Custódio de Faria was a Catholic, no less!

Fr. José Custódio continued his research into the subject up to the year 1811, when he was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Marseilles. The Imperial Almanac of 1811 records that he lived there a year and was elected member of a medical society. Since he had no medical qualifications, the membership can only be attributed to his skills as a magnetizer. But for some mysterious reason, he was transferred, in fact, demoted, to the post of auxiliary professor at the Academy of Nimes. He felt slighted and frustrated and, unaccustomed as he was to life in a small city like Nimes, he returned to Paris, in 1813, in search of greener pastures. Unattached to any institution, he initiated his course in magnetism on 11 August 1813, 49, Rue de Clichy.

Sessions

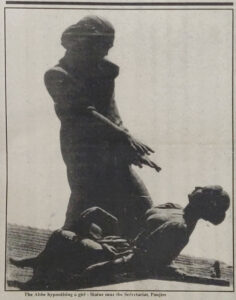

The sessions were held every Thursday, on an admission fee of five francs only. He began with a lecture in halting French. The audience, which consisted largely of women, paid scant attention to this part of the session; their eyes were set on what was to follow – his experiments to substantiate his theory.

Contrary to the claims made by Mesmer, the he could control the body fluids of his patients and rectify their course through special methods invented by him, Fr. José Custódio very humbly put forth that not all individuals could be hypnotised, and that the degree of response to his hypnotic powers necessarily varied from person to person. He was the first to establish that hypnotism was a science of suggestion.

Fr. Faria’s method consisted of a series of well-reasoned and effective actions: he got the patient to sit comfortably and, through concentration, to relax, imagining that they were going to sleep. When the patient was ‘tranquil’, he gave the command, ‘Sleep!’ and, if necessary, repeated it, with a certain degree of urgency, three or four times. If he failed, he would either sportingly give up or try other methods.

The sessions became the rage of the town. There were detractors, critics and skeptics, no doubt. Once, a journalist attended his session and then unjustly criticised and ridiculed the priest in the press. At another session, a leading stage actor, Potier, offered himself for his experiments. He feigned to be in a trance and suddenly rose to say, ‘Ah, Abbé! If you magnetize others as well as you magnetized me, you don’t seem to be doing much.’

Fr. José Custódio put up very well with all such betrayals. He also withstood quite stoically criticism from the clergy and Rome, who then viewed his experiments with suspicion always on the look-out for diabolical influences therein. But the priest always expressed respect for the Church and a firm desire to stay within the Catholic fold. ‘Un esprit supérieur,’ as his disciple Gen. Noizet said of him, he wished to convince the Church that his experiments were fully within the natural realm and that there was no magic or witchcraft involved.

Thus, Fr. Faria took everything in its stride. Only once did he break down, when at Potier’s request the playwright Jules Verne put up a play, on 5 September 1816, the Variétés, titled La Magnétismomanie, ridiculing the Goan priest.

Sad end

The time was now ripe for Fr. Faria to stop his activities. He retired soon thereafter, rendering priestly services in exchange for boarding and lodging.

During the last years of his life, he decided to organize his material in book form. It was an ambitious project in four volumes, of which only the first one is known to have appeared. It is his magnum opus is titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou Étude de la nature de l’homme (On the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study on the Nature of Man). In it he referred to the shameful play:

‘With regard to Magnétismomanie, I cannot ask which laws permit the modern Terence to expose an unknown foreigner to public ridicule. I presume that even the savage would be ashamed to insult his kind, which has nothing in common with actors and the theatre.

‘Far from me the idea to disturb public pleasures: But I might have added to Magnétismomanie a new scene – an extremely pungent one – had my condition not prevented me from doing so, and had my own aversion for such amusements not kept me away from playhouses.’

According to one biographer, by a strange coincidence, the day of his death, also marks the release of his book. His famous words, ‘There are evils that sometimes do good to those who discern their utility,’ might have very well served as his epitaph – if only he had the money for a decent burial. He died at the age of 63, unsung as he was born. A life full of ironies, for born of a rich family he died poor; born of parents who were in love, they separated after his birth; a man with original contributions to posterity, he died with no godfathers to promote his name.

(Herald Illustrated Review, Panjim, Goa. Vol. 95, No. 30, February 1-15 1995. Slightly updated version)