Konkani before and after Dalgado

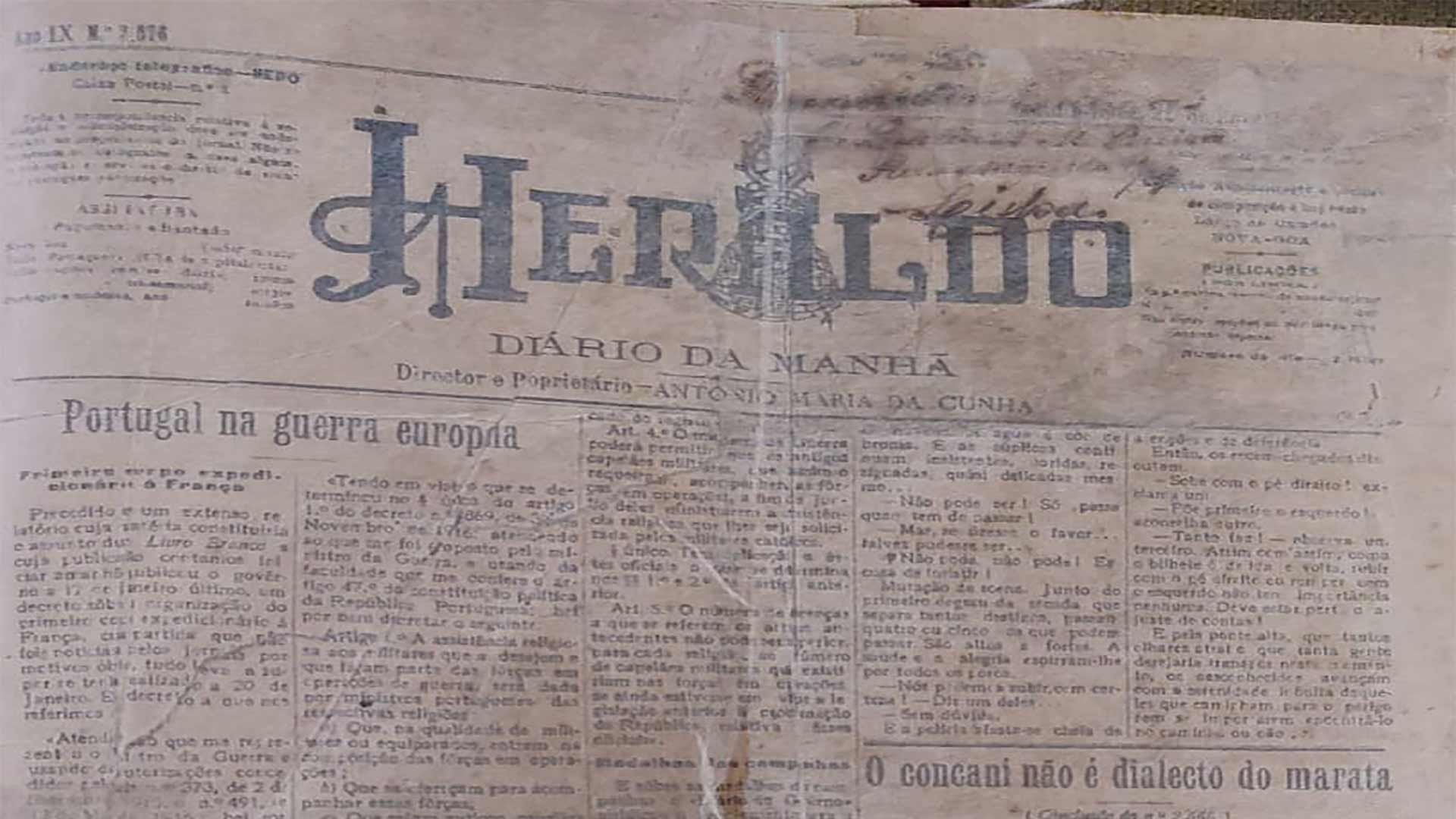

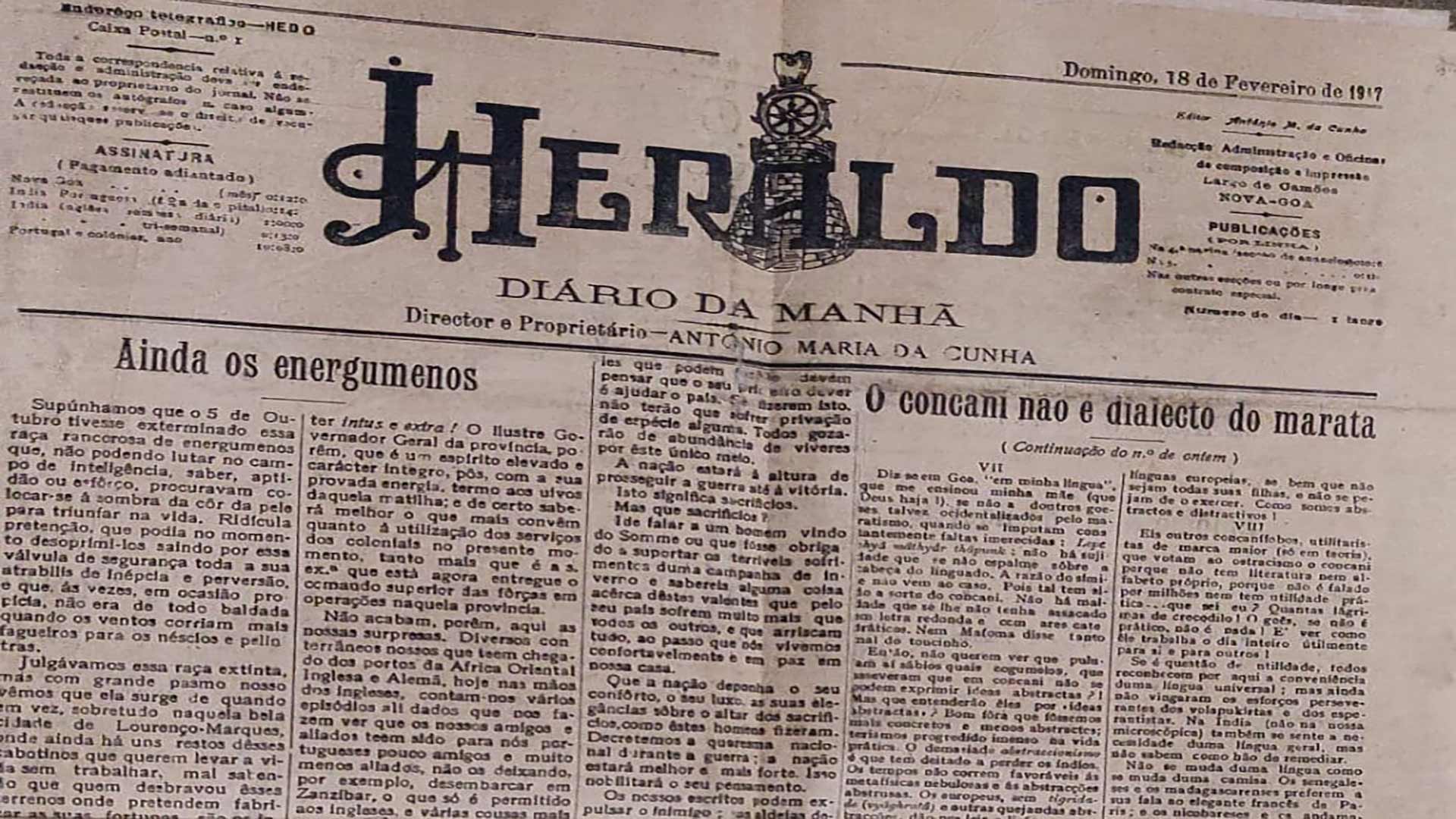

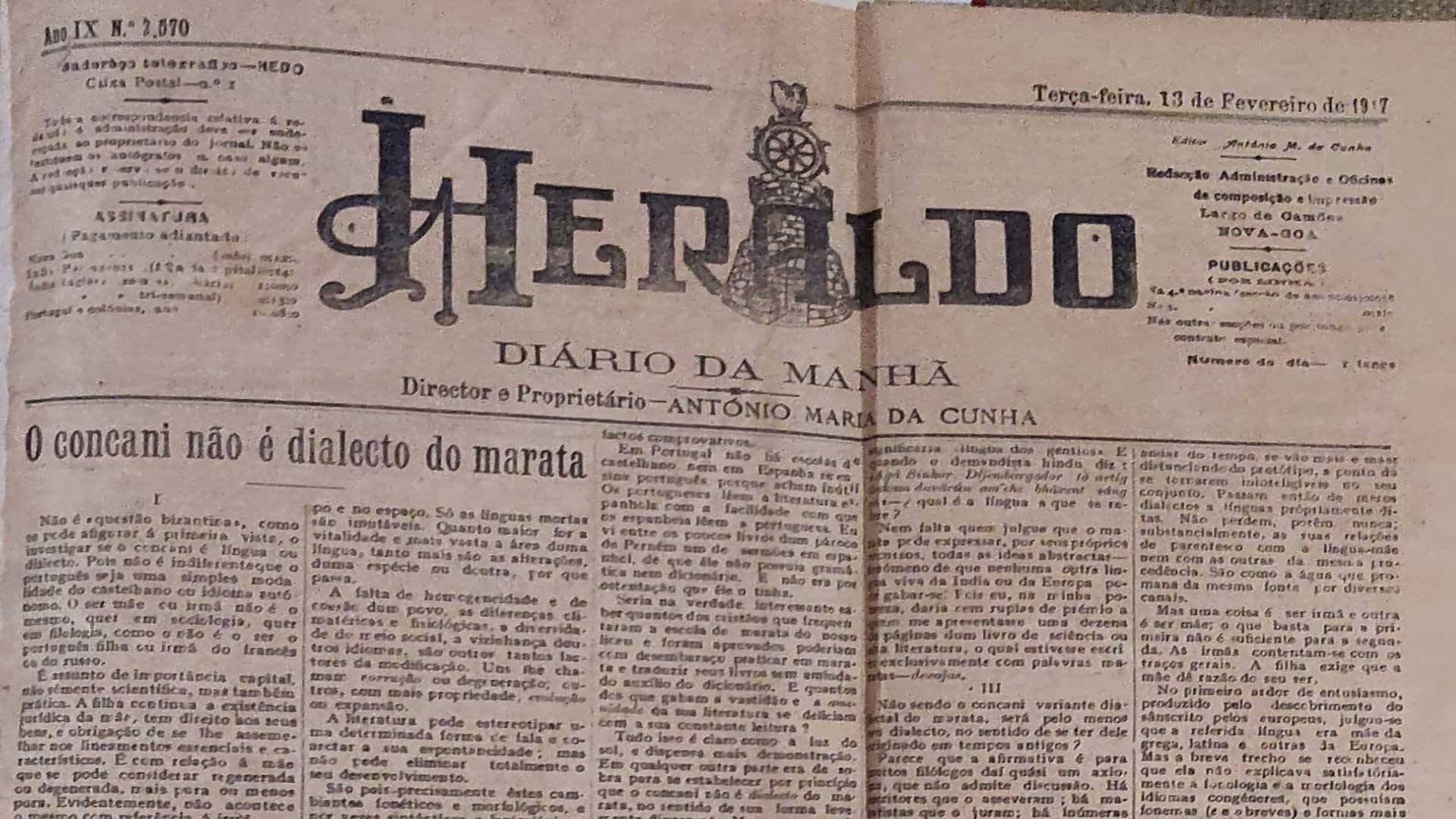

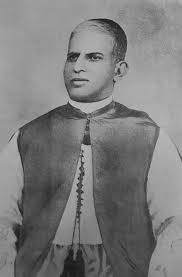

In 1917, Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, an internationally renowned Goan linguist, forever changed the course of the Konkani-Marathi controversy. In a nine-part series titled “O concani não é dialecto do marata” (‘Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi’), published in the Panjim daily Heraldo, he analysed the linguistic and grammatical characteristics of Konkani, demonstrating its identity as distinct from that of Marathi. But, then, what events led Mgr. Dalgado to write the series?

Fabricated controversy

The Konkani-Marathi controversy is not as ancient as it might seem; it is a nineteenth-century fabrication. Konkani, which, like Marathi, evolved from Prakrit, began to make rapid strides in the linguistic, lexicographic, and literary fields, thanks to the ingenuity of European missionaries in sixteenth-century Goa. It is another matter that their interest began to wane, and indifference turned into state hostility, to some extent, at least on paper. This brought the first modern literary period of Konkani literature to an inglorious end.

In the eighteenth century, literary production in Goa was conspicuous by its absence, due to the shutdown of the printing press. As a result, not only did Konkani get relegated to the background, but Goa itself became a backwater. Even so, there was not a doubt about Konkani’s linguistic status until the year 1807, when John Leyden dubbed it a dialect of Marathi. His ideas began to gain currency in British India. When those echoes reached Portuguese India, Konkani was excluded from the curriculum of the first state-owned schools set up in 1831. By now, in the new Liberal regime, it suited Goan Catholic elite to adopt Portuguese as their cultural language, while the Hindu elite continued to seek refuge in Marathi and turned to Portuguese in the following century.

Meanwhile, in 1858, J. H. da Cunha Rivara’s famous essay on the Konkani language (Ensaio histórico da língua concani) decried Goa’s contempt of its native language and defended its dignity. His realisation was perhaps a byproduct of a new Orientalist consciousness, which prized the rediscovery of indigenous languages. But alas, it is Marathi and not Konkani that drew the benefit. In 1869, at the behest of Goa’s official translator Suriagy Ananda Rao, the state government banned the use of Konkani, while Marathi ruled the roost at the Panjim Lyceum.

A decade later, when R. G. Bhandarkar in Bombay reiterated Konkani’s dialect status (cf. Wilson Philological Lectures, 1877, a series of seven lectures on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages), scholars favouring the dialect theory slightly outnumbered those favouring the language theory. But a fitting reply awaited Bhandarkar in 1881, when José Gerson da Cunha systematised and coordinated the arguments of the language theory in his Konkani Language and Literature. Nonetheless, in 1905, the Linguistic Survey of India, published by the British Government, buttressed the dialect myth.

Divided Goa

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

While the Konkani movement was thus gaining momentum within the community in Bombay, back in Goa, Thomaz de Aquino Mourão Garcez Palha and Fernando Leal, two mestiços (persons of mixed blood, Portuguese and Goan), who had probably caught the Orientalist bug, began a crusade for the “resurrection of Konkani”. They were supported mostly by members of the Goan Catholic elite.

As regards the Hindu elite, in 1916, when the ayurvedic physician Dada Vaidya (Ramachondra Panduronga Vaidya) spoke in Konkani at Goa’s first Provincial Congress, Marathi writer Xamba Suriarao Sardesai shouted him down and followed it up with a two-part article disparaging the Konkani movement. The division of Goan society was complete, not only between educated Christians and Hindus, but also within the Hindu community.

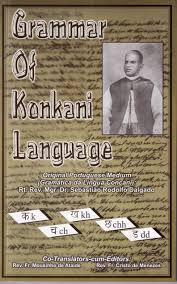

By February 1917, therefore, the stage was set for Dalgado’s intervention from distant Lisbon. The tireless Goan Catholic missionary was now on a mission to prove Konkani’s credentials as a language. He had published a Konkani-Portuguese dictionary in Bombay (1893), and a Portuguese-Konkani dictionary in Lisbon (1905), both of which used the Devanagari and Roman scripts. The university professor and Fellow of the Portuguese Academy of Sciences was an authority on the influence of Portuguese on Asian languages, and his thoughts kept returning to Konkani. Significantly, his last unpublished work was a Konkani Grammar, which Fr Mousinho de Ataíde translated into English in Dalgado’s death centenary year, 2022.

Decisive entry

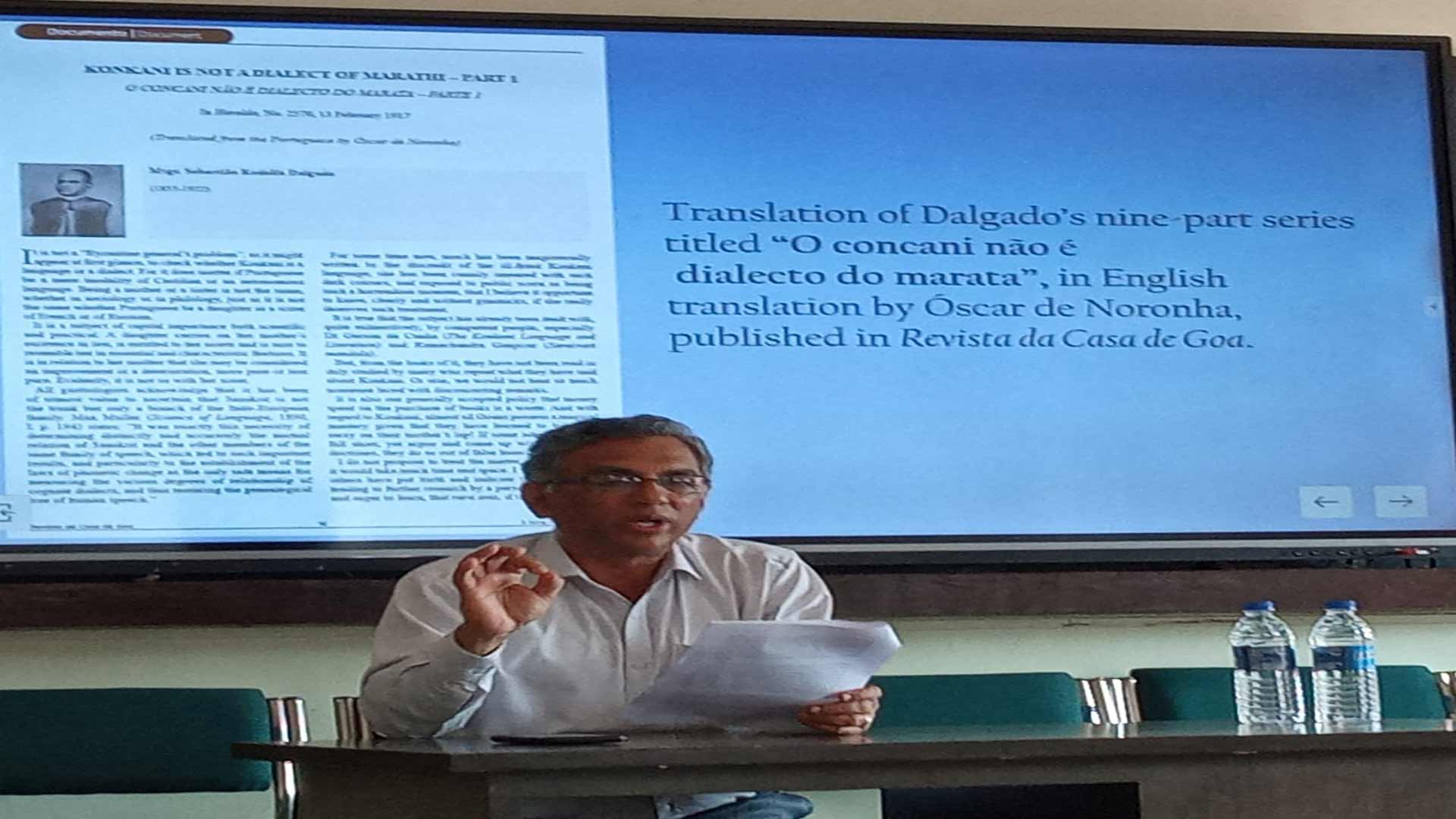

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s entry was decisive. It was a watershed moment in the history of Konkani Studies. Portuguese-language newspapers in Goa as well as bilingual papers in Bombay began to comment on Dalgado’s efforts in the field. After him, Jules Bloch showed how distinct Marathi was from Konkani; S. M. Katre paralleled Bloch’s book by writing The Formation of Konkani, and together with V. P. Chavan, helped further Konkani’s position as a separate language.

Varde Valaulikar’s writings continued Dalgado’s work of demonstrating Konkani’s individuality. Curiously, Shenoi Goembab began by writing in Marathi, and after switching to Konkani, first wrote in the Roman script. Seven of his twenty-nine books are in the Roman script. In fact, there was no Konkani worth the name in the Devanagari script in Bombay, and much less in Goa.

Perhaps Dalgado and Valaulikar never met or exchanged correspondence, but they shared the same vision. Valaulikar, who knew Portuguese, must have read Dalgado’s rejoinder to Xamba Sardesai. While Valaulikar carried out a literary crusade in Bombay, Dalgado’s academic legacy was kept alive by his pupil Mariano Saldanha in Lisbon. Dalgado died in 1922, and Shenoi Goembab in 1946. In 1952, Mariano Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth All-India Konkani Porixod held there. As a votary of the Roman script, Saldanha’s address was printed in the Roman script.

By the 1950s, the demand for linguistic states had gained significant momentum, leading to the creation of the Telugu-speaking Andhra out of the State of Madras. Much earlier, the Indian National Congress had organised its provincial committees along linguistic zones, signalling an early form of the concept. Dalgado and Valaulikar’s vision of Konkani in the Devanagari script dovetailed into that concept, whereas Saldanha envisioned the Roman script for Konkani in Goa. It did not materialise in the post-1961 scenario, for obvious reasons.

Goa post-1961

It was an entirely new ballgame after Goa got into the Indian Union. Maharashtra had laid claim to Goa, deeming Konkani a dialect of Marathi. The Goan elite, which was once divided between Portuguese and Marathi, leaving Konkani to fend for herself, now realised that only Konkani could help preserve their identity. It was a David and Goliath situation, in which Konkani won because the language was on the people’s lips and nobody could take it away. Its literature was perhaps not on a par with best in the country, but it had a strong foundation built by Dalgado and Valaulikar.

Hence, while Valaulikar is regarded as the Father of Modern Konkani Literature, Father Dalgado, by his fundamental contribution to the development of the language, ought to be regarded as the Grand Father (pun intended) of Modern Konkani. Their impact was felt at the time of the Opinion Poll and when Sahitya Akademi recognised Konkani as a literary language; when Goa achieved statehood and Konkani became the state language, and when Konkani was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

Thereafter, Konkani came into a privileged position, as never before. It would seem like a time to consolidate had arrived. For instance, in the Konkani world beyond Goa, it would pay dividends to make the most of the multi-script situation; but that was not to be. In Goa, the issue of script remains Konkani’s Achilles heel. The sooner this is resolved the better, to ensure the interests of all the user communities; their wellbeing is bound to produce positive results for the popularity and expansion of the language. The more the scripts the better.

Case for the Roman script

It is also a time for some reflection. Has the shared legacy created by Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab been put to creative use? It would be interesting to consider what their response would be to our globalised world. How would they respond to demands for recognition of the Roman script in today’s multilingual and multicultural world? Would they consider it an opportunity to woo back Konkani speakers at home and in the diaspora, and to win new speakers from across the big wide world? Would they appreciate the possibility of Konkani finally becoming at once a means of communication and identity marker?

After all, living languages are dynamic, and no script is perfect. Goykanadi was the earliest known native script that Konkani used, before it was supplanted by others. Similarly, the earliest known script for the English language was the Anglo-Saxon futhorc. From the seventh century onwards, the Latin alphabet began to replace the futhorc, though they coexisted for a time in England.

It is the same in India. The Latin or Roman script is not to be considered foreign; it is as Indian as the English language in the country. If the English language can be made official, so can the Roman script, or any other for that matter, if numbers and the volume of work justify it.

Not to let script remain a divisive issue, would Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab, then, consider letting Goa be the first state in the Indian Union to successfully resolve a multi-script situation? Any script that has worked in the past ought to work in the future. This applies to the Roman script as well. Surely, Dalgado’s mission was to save the language over and above the script.

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi – 9

Part 9 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata"

by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

(In Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2576, 22 February 1917, pp. 1-2)

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

An important question now arises, which can also be regarded as a sensible and weighty objection. It being impossible, as a result of those significant discrepancies, that Konkani, as we know it, be a dialect of Marathi, how does one explain so many analogies, especially morphological, between the two languages?

It is a complex issue. It demands a lot of learning and long elucidation. In addition to philology, it needs history and ethnology to step in. I turned it over many times in my mind, but did not obtain satisfactory and definitive results, for want of some indispensable elements.

Hence, I am not on firm ground. I may put across my point of view if I get some respite from my occupations, and I find sufficient motivation, for elderly people generally flounder.

Meanwhile, responding to frantic demands, I will declare that I would not be averse to the hypothesis that Marathi is the subsoil (not mother, please note) of Konkani or the superinduction or superfetation. Which of the hypotheses is more plausible, if there is need of any?

This time my only goal was to break a lance for ‘my lady’ and to avenge the wild invectives that cowardly hands threw at her, mercilessly and with iron fists, but also – sorry to say! – with neither knowledge nor conscience. I end crudely, with not much of a method and hurriedly, so as not to delay the typographic proofs of more useful and less sentimental and abstract work. Maybe some minor slips escaped my notice – a fact that is understandable for him who works from his bed and on subjects that require frequent consultation of books.

I do not mean to say, however, that nothing has been written about Konkani that is sensible and deserving of praise, nor that I am displeased by opinions differing from mine. On the contrary, I disapprove of ipse dixit, and I believe that intellectual slavery is the worst kind of slavery. It is not something in which we say Roma locuta est, lis finita est.

But there are opinions. Opinions expressed without full grasp of the subject, albeit with literary trappings, only with the itch to show off and to give tit for tat, have no greater value than those coming from inmates of a mental asylum. They are combated, not with a view to convincing the opinion holders, but to prevent those opinions from getting established.

It goes without saying that, whoever lacks even elementary notions of general philology, and is unaware of the origin, history, phrases, dialects, literature, nature of vocabulary, grammar of a language, and her relations with her sisters and neighbours, cannot expatiate on their merits or demerits, their progress or degeneration, their purity or corruption. Ne sutor ultra crepidam.

Speaking a language by listening does not qualify one to deal with its philology, which is a completely different thing. Adolfo Coelho and José Maria Rodrigues know more about Latin philology than Cicero and Horace did; and Max Muller and Brugmann know comparative Sanskrit philology better than did Panini, the prince of the world's grammarians.

But this is not how they think in Goa, for lack of common sense and intellectual discipline. Freedom of thought and of speech is no excuse for nonsense bordering on insanity. The Hindu who, on the occasion of the proclamation of the Republic, entered a church over there, holding a cigar in his mouth, proved, if anything, that he was utterly uncouth.

How many of those who have written about Konkani would know the right declination of a noun or conjugation of a verb, or how to analyse a passage by breaking down the words, distinguishing themes and inflections and indicating the etymology? Just how many people mistake the past tense of transitive verbs for active voice, and the sentence – hânvem ambó kheló – for ‘I ate a mango’, when, in reality, it means ‘the mango was eaten by me’!

It seems as though general belief over there has a say in everything that concerns our communities: Zâmkún zhânkún gâmvkar zâtá; one becomes a ganvkar through sheer chattering.

That results in a lot of vines and few grapes. If competent people took care to teach; if the ignorant cared about learning; if they talked less and worked more, it would be a win-win. We are so done with chatterboxes.

Fortunately, in the midst of disconcerting mists, a gleam of light is not lacking. I was deeply moved to learn that my venerable friend and most exemplary priest, Father Casimiro Cristóvão de Nazareth, had offered the local government a Portuguese-Konkani vocabulary, put together by him in collaboration with some knowledgeable people, to be published and distributed to schools.

I have no doubt that the work is of great merit. Father Nazareth, who trained from early years at the school of Filipe Néri Xavier and Miguel Vicente de Abreu, and who has been a busy bee throughout his life – tanquam apis argumentosa – and is a walking library of useful information, does not produce fake stuff nor is he a publicity seeker.

But to think that an eighty-five-year-old man, and moreover, blind like Tobias – quia aceptus eras Deo – is still working and making it a point to be of service to the country, while so many young people exhaust themselves with an hour’s reading and need to amuse themselves with manille and suposta and give in to banal and sinful talk: what a striking contrast and what an edifying lesson!

It pains my heart to remember – and this happens so often! – that the Portuguese government declined to publish his Mitras Lusitanas, a product of much labour and an ample mine of such precious information, collected with great tenacity from all the accessible sources. It occurs to me now that Counsellor Jaime Moniz told me that he would bother him with requests for books to read or to send to Rachol Seminary.

In any other civilized country, that monumental work would have been welcomed as a national glory, and an award given to its author, who neither made a profession out of his calling nor aspired to lucrative and showy positions. Of him, certainly, one cannot say that he was ‘toddy coconut tree’ – suretsó madd.

Certain happenings in Portugal lead people to believe that they live in some Zululand. From Rome, they recently sent me Pietro della Valle’s book, which cost twenty francs. The Customs office of Lisbon valued it at twenty escudos – over four times – and charged 1700 réis as duties! The bookseller's receipt was presented and it was proposed that they keep the book for fifteen escudos, thus making a profit of five. They threatened that they would value higher. And all that just because of the shoddy, dirty parchment binding, for which I didn't pay a penny!

Patriotism is a good and praiseworthy thing. Jesus Christ shed tears foreseeing the future ruin of his homeland. But I reject patriotism that forces me to distort the truth and trample on justice.

In conclusion, I must declare, in order to appease my conscience, that those vague references are not tantamount to personal contempt for those targeted, whom I know not and wish all the best, as well as all humanity. I would have liked to be entirely doctrinaire, if the subject so allowed it. I earnestly request the reader not to be curious to investigate who is hinted at in the above allusion. It is about doctrine, not people. Veritas et caritas super omnia.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 31, Nov-Dec 2024, pp 45-48

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 8

Part 8 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata" – Parte VIII

by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

(In Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2575, 18 February 1917, p. 1)

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

Here are other Konkaniphobes, major utilitarians (only in theory), who ostracise Konkani because it has no literature or alphabet of its own; because it is not spoken by millions nor has any practical use… what do I know? How many crocodile tears! A Goan, if not practical, is nothing! One must see how usefully he works all day for himself and for others!

If it is a question of utility, everyone recognizes over here the convenience of a universal language; but the persevering efforts of the Volapukists and Esperantists are still not vindicated. In India too (not in our microscopic one) the need is felt for a general language, but one knows not how to resolve it.

You can't change your language like the wind. The Senegalese and the Malagasy prefer their speech to the elegant French of Paris; and the Nicobarese and the Andamanese give more value to their speech than to the booming English of London. The Hottentots and the Zulus would not give up their sibilants and monosyllables for the best language in the world.

A self-respecting son does not subrogate his mother, however ugly, poor, ragged, pustulous, for a queen, beautiful as Venus, adorned with byssus and purple, with diamonds from Golconda, pearls from Ceylon and rubies from Pegu. He doesn't ‘kick’ her, as they say there; he doesn't reject her, loathe her; he hugs her, kisses her, helps her, boosts her, lavishes her with all the care and indulgence he is capable of. This is what St John Chrysostom teaches us, speaking of children, who in many ways are our teachers. Or else, the Son of God would not have said: Unless you become like little children, you will not enter the kingdom of Heaven.

I won’t be surprised if over there they know not that in Kanara there is a language, sandwiched between Malayalam (language of the Malabar) and Kannada; it has no literature, no alphabet of its own, is spoken only by five hundred thousand, is stuffed with Sanskrit, Kannada, Malabarian and Hindustani words. It is Tulu or Tulava, which bears more Portuguese terms and closer relations to Konkani than Kannada does. In the opinion of Caldwell and other grammarians, it is nonetheless one of the more developed of the Dravidian family. And till date no one has proposed that it be replaced by one of its more powerful neighbours that lend it their alphabet. On the contrary, Protestant missionaries promote it diligently, by publishing grammars, dictionaries, and other works.

If, however, Goa’s progress and happiness depend on Marathi being the vernacular and vehicle of primary education, may a Hercules arise who will do away with the Konkani hydra; and I will only have to sing his praises, mimicking Pasquin: Quod non fecerunt lusitani, fecerunt canarini.

And then, let's hope that some Nobel prizes will end up in our homeland, as did one, two years ago, in Bengal (to Sir Rabindranath), and that there will emerge an authentic genius, like Chandra Bose, who astonished scientists of Europe and America with those wonderful demonstrations of plant physiology.

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, Sep-Oct 2024, pp __

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 7

Part 7 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata – VII", by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado (1855-1922)

Published in Heraldo, Vol. IX, No. 2575, 18 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha and published in

Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 29, July-August 2024, pp 29-31

Lepechyâ mâthyâr thâpunk: there is no dirt that does not spread over the flounder’s head. This is said in Goa, ‘in my language’, which my mother (may she rest in peace!) has taught me, even it is not that of other Goans perhaps westernised by Marathism; when unwarranted faults are constantly imputed. The reason for the simile is beside the point. For such has been the fate of Konkani. No evil has been left unattributed to it in print and with a professorial air. Not even Mohamed has so viciously bad-mouthed bacon.

Do you not see, then, that the place is swarming mushroom-like with learned men, who state that in Konkani one cannot express abstract ideas? But what do they mean by ‘abstract ideas’? If only we could use more of concrete rather than abstract language; we would have made much progress in practical life. Too much of abstractionism is what is destroying the Indians. The present times are not conducive to nebulous metaphysics and abstruse abstractions. The Europeans, without tigritude (vyaghratā) and other such abstractions, provide us with laws and lessons.

But is it true that the spoken language of the Goan Christians has not a word to denote abstract ideas? And the current and past preachings, do they only deal with concrete things about the cult of linga, yoni, xaxti, Betalla, king cobra? And so many manuals and devotionals, besides books and newspapers that are published, especially in Bombay, don't they contain abstract ideas?

And the Christian catechism? Surely, that's not Marathi. A philological authority has already stated that pottárth, alpabhojan, sadaiv, and other such terms do not exist in Marathi and Sanskrit or do not have the connotations that we assign them. Now, the catechism has hundreds of words like those to designate dogmas and mysteries, virtues and vices, gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit, dispositions for the sacraments, etc. Are they all concrete words?

Hence, I would have liked to be in Goa and at a public contest see who has abstract ideas, whether a Christian lad with just the knowledge of the Konkani catechism, or a Hindu lad, of the same age, with wide knowledge of Marathi. I do not for a moment hesitate to say that the Christian would carry off the palm.

The reason is obvious to those who know what generally professed Hinduism is. It is in essence more elastic than rubber. That is why it does not have a catechism, a code of doctrines and precepts. Ask a cultured Hindu to state in a few words what he should believe and practice in accordance with his religion, and see the result. It would not be the same with a Buddhist or a Jain. An orthodox Hindu is he who accepts the Vedas in theory, even if he has not seen them, and caste distinctions in practice, even if he cannot explain himself. The rest hardly matters. Philosophers and theosophists have mercilessly rattled the Vedas with their doctrines, but did not openly repudiate them. And that was enough.

If, to express abstract ideas, the Marathists constantly turn to Sanskrit vocabulary, does not Konkani have the same right? Or is Sanskrit the monopoly of the Bhonsles, and no other can touch it? European languages have equal right at least to Greek and Latin, even though they are not all their children; and they do not hesitate to exercise it. How abstract and distracting we can get!

Ponnji atam mhatari zalea

Arvind (Ana) N. Mambreachi lhan kotha

Arvind (Ana) N. Mambreachi lhan kotha

Devanagarintlem Romi lipiantor ani Purtugez bhaxantor korpi – Óscar de Noronha

Ponnji: Manddviche deger patllaun boxil’lem hem ek xhar. Hanga motarint pavta. Bosint pavta. Bottint pavta. Bott zalear Ponnjechea sam’ki kallzak tenkta. Ti matxi usram pavli zalear, polasint bhitor sorun mukhel-montreak zap diun magir tumcheani ghora vochum ieta.

Xhar

Ponnji Tiswaddint asa. Tiswaddiche lokvosti sadharonn lakhavoir. Poikim Ponnjent sadharonn satt-ek hozar ravtat. Pavsachea tempar Ponnjent paus khub poddta. Rostear zollim-mollim khatonnam zatat. Passei-hancher xello zata. Punn paim nisrun mat konn poddnant. Karonn Ponnjeche lok toxe toklen fin. Xiam tempar xim khub khata. Punn Ponnjekar kudkuddnant. Fokot gimant kalor khub zata ten’na mat’ te bettech taptat. (Kaloran Ponnjekaranchi xir rokddich titt zata).

Ponnjent rajachi ek polas asa (tika Palácio de Idalcão mhonntat). Ponnjentleo her soglleo polasi Ponnjekarani bandlea. Devulvaddear, Altinho, Santa Inez ani Campalar g-h-e mhonnun polasi asat. Ponnjekarancho poiso soglo tangelea ghorani ani motarini otla. Hangasol’lea choddxea ghorank monxanchim nanvam – Govinda, Sushila, Gurunath, Souza, Mascarenhas, Heera, Prema, Dempo, Velho, oslim.

Ponnjent ghoranchea zoteank nogram mhonntat – Adarshnagar, Neuginagar, Kundaikarnagar bi. Hea disamni don sorkari odhikari devulvaddear ghoram bandtat. Tanchim nanvam – Bhaunagar and Tainagar. Campalar eklo blakist ghor bandta tache nanv – Komagattamarunagar.

Ponnjechea nogramvori nogram akh’khea sonvsarant na mhonnttat. Poir Amerikechea President Ford-an Washingtonak khoim eke election-hache sobhent sanglem, mhaka tumi venchun dixeat zalear tumkam hanv Ponnjechea Kundaikarnagaravori ek nagar bandun ditolom.

Tibluchem ghor

Tibluchem ghor khub lhan. Tantunt monxam him: avoi, bapui ani Tiblu. Tiblu ekloch zolmak ail’lo. Zolmak ietnach ievzupak lagil’lo, ho sonvsar oso kitem? Lhanponnan Tiblu roddonaslo. Khub usram to ulounk lagil’lo. Ulounk laglo tori to uloinaslo. To fokot ievjitalo. Vachtalo. Boroitalo. Chitram kaddtalo. Uloi mat’ naslo.

Roste

Ponnjent roste bore xekan’xek patoll’leat. Ponnjeche lokamvori Ponnjeche roste-i bore susegad-xe. Disbhor jemet astat. Ponnje eka rostear choltanach monis dusrea rostear pavta. Ponnjechea pattear bhitor soril’lo monis soroll cholunk lagot zalear João Castro - José Falcão - Dada Vaidya rosteavelean bodh Ponnji sompta thoim pavum ieta. Hea rosteanchi ekuch bori gozal mhollear Ponnjechea lokank zati-kati-dhorm lagtat te tankam lagonant. Hea rosteanchea nimitant Dada Vaidya, dotor Atma Borcar, Shirgaonkar he babdde Afonso de Albuquerque, Cunha Rivara, Bénard Guedes, Governador Pestana hanche pongtik bosunk pavleat. Ponnjent 5 October, 18 Jun, 31 Janer oslei roste asat. 31 Janer ani Rua de Ourém hanchemodim il’lexem ek Portugal asa ani Devulvaddear ek supul’lo-so Maharashtr asa.

Lok

Ponnjek lambai-rundai bori asa. Punn itleim asun Ponnjekaranchi monam sam’kim oxir. Toxe Ponnjent sogle toreche lok asat – bore, vaitt, sadhe, xanne, pixe, sadhe-bore, bore-bore, xanne-bore, pixe-bore, sadhe-xanne, sadhe-pixe, xanne-xanne (dedd-xanne), pixe-xanne. Hanga vepari, blakist, professor, dotor, advogad, ijiner, oxetoreche-i lok ravtat. Mineir mat vhoddlexe nat. Punn je asat tanchebogor her lokanchem paul ukholna. Dil’lintle sogle montrilegit tankam vollkhotat.

Tibluchem vachop

Tibluk lhanponnapasun vachpacho nad. To ghorant zollim-mollim bosun vachtalo. Bhailea humrear, randche kuddint, iskadesokla, magildara. Tiblucho bapui bolkanvant ontorraxtrik rajkornnacher bhasabhas kortalo ten’na Tiblu khoimtori khanchi-konnxak bosun chitram kaddtalo.

Zantto zatokuch Tibluk konnetori mhollem, Tiblu, tum laibrorint kiteak vochonam?

Tibluk tea monxean Sorosvotimondir dakhoilem. Tedischean Tiblu thoimsor vochun bosunk laglo. Sokallim iskolant vochop. Jevop-khavop, abheas korop, chea ghevop. Magir laibrorint vochop. Bodh ratcho attank ghora portop. Jevop-khavop, chitram kaddunk bosop. Il’lo il’lo korun Tiblu borounk-ui xikil’lo. Kovita korunk lagil’lo…

Nanvam ani zati

Ponnjent eka nanvache, dotti nanvanche lok khub. Poi, Bholo, Poi-Bholo; Duklo, Bhobo, Duklo-Bhobo; Bhobo, Kakulo, Bhobo-Kakulo; Souza, Paul, Souza-Paul; Kamat, Ghanekar, Kamat Ghanekar; Sequeira, Nazareth, Sequeira Nazareth. Khottkhotto, Zingddo, Buttulo, Buddkulo, Topanxett oslei monis Ponnjent ravtat. Ekach nanvache hanga khubxe lok melltat: Dotor Costa, Professor Costa, Advogad Costa; Professor Nadkarni, Advogad Nadkarni, Dotor Nadkarni; Dotor Boddko, Advogad Boddko, Professor Boddko. Konnso mhonttalo, Santa Inez oxetoren 15 Desai (Sardesai dhorun), 12 Kamat ani 9 Nayak ravtat.

Svotantrataiepoilim Ponnjent donuch zati asleo – poixekar ani Ponnjekar. Mineir, blakist, vepari, empregad he sogle poixekar. Her sogle Ponnjekar. Mhollear Bahujan-samaj. Svotantrataie uprant hatunt anik don zatinchi bor poddli – montri ani deputationist. Poinkim deputationist hi scheduled caste.

Ponnjeche montri khub uloitat. Zai title uloitat. Naka titlei uloitat. Ponnjekarancheo sobha montreambogor zainant. Montreanchem pavl sobham bogor ukholna. Sadharonn montreanchem uloup oxem asta:

Janten hem korunk zai.

Janten tem korunk zai.

Janten soglem korunk zai.

Sogle Ponnjekar (poixekar ani Bahujansamaj) montreank khub lekhtat. Tantle tantunt poixekar tankam chod lekhtat. Adlea kallar zanche hat Purtugez rajeakorteomeren pavil’le tanche hat atam montream-meren pavleat.

Ponnjent man koro tigank: montreank, montreanchea parentank ani montreanchea vollkhicheank (hantunt sezari aile). Uprant sorkari odhikoreank. Montreank zaum odhikoreank zo vollkhona to Ponnjent sandloch.

Xinu

Xinuchi pirai 60 vorsam. Tachem borem chol’lam. Vepar, min, blak, rajkaronn… to sogleant asa. Hachem ghevop taka divop ho tacho vepar. Zachem ghetlam tachem naddear to min kaddta. Zaka dilam tachea malvozar to blak korta. Zachem ghetlam ani zaka dilam taka gheun to montreanger ani amdaranger favtti marta. Sod’deache assemblintle don montri ani dha amdar aple, Xinuchem mhonn’nem.

Sonstha

Lions Club, Rotary Club, Junior Chamber, Goa Chamber of Commerce, Konkani Bhasha Mandal, Marathi Sahitya Sevok Mandal, Bhagini Mandal, Mine Owners Association, Exporters’ Association, Indo-Soviet Cultural Society, Rose Society, Vivekanand Society… kitleosoch sonstha. Chear Ponnjekar ektthaim ailear panch sonstha kaddtat. Hangasol’lo ek-ek monis dha-dha sonsthancho membr asta. Ponnjentle khubxe vhodd monis hea sonsthanche membr. Hangsol’le lhan monis vhodd monxancher uloitat. Vhodd monis odik vhodd monxancher uloitat. Sorkar jantecher uloita.

Ponnjent vhoddlixi janta na. Dispotti ji hanga janta dista ti bhailea ganvsun – Merxe, Kalapur, Raibandar, Tallganv – ail’li asta. Ken’na-ken’nai ti Kansavli, Kolvall, Divaddi, Pednem, Sall, Bannavli hangacheanui ail’li asta. Khasa Ponnjent ji il’lixi janta asa ti Molleant, Bhatleant bi ravta. Poixekar Altinho, Campalar ravtat. Ponnjecho Devulvaddo ani Santa Inez hanga donui toreche lok ravtat.

Altinho eka kallar fokot vhodd monisuch ravtale. Atam thoim montri, sorkari odhikari ani pixe-i rautat. Montri ani poixekar motarani bhonvtat mhonnun her monxapasun te matxe veglle distat.

Lions Club, Rotary Club hancheo sobha sodam vhoddlea hotelamni zatat. Konkani, Marathi mondollancheo sobha lhan’xe kuddani zatat. Te club ganv poske ghetat. Monddolam vorsbhor sompil’lea sahiteakanche zolmdis ani mornndis manoitat. Reformad sorkari empregad vell pasar korpakhatir hea kareavollink ietat. Vivekanand ani Rose sosaitianchea songit kareavollink/prodorxonank mat sogle Ponnjekar bail-bhurgeank ghevun vetat.

Tibluchi dairi

Poir igorjechea festak mhaka Xinudaad mell’lo. Khub uloilo. Chaitr punvechea nattkant aplea putak part mell’la mhonnun sangtalo. Mhaka mhonnunk laglo, ‘Tum kitem korta?’ Hanvem mhollem, ‘Chitram kaddtam, kovita boroita.’ To mhonnunk laglo, ‘Video kiteak vikina?’

Nustem

Baki Ponnjekarank nusteabogor zaina. Bazarant nustem borem ieta. Sungttam, moteallim, vel’leo, pedve, balle, korchanneo, mudd’doxeo, xenvtalleo, kallundram, sorgem, bangdde, xenvtte, kol’leo, moreo, sangttam, visvon, gobre, tisreo, khube, xinnaneo … Soglem tea tea tempar ieta. Punn sogleank tem ghevop zomona. Sogle bazarant dispotte nustem haddunk mhonnun vetat. Bhitol’le orde tem mharog uzo mhonnun viktem ghenastanam porte ietat. Horxim ho ‘uzo’ poixekaranchea ghoramni dispotto pett’ta.

Nustem khavun, nhid kaddun, uttun, chea ghevun Ponnjekar sanjche passeik vetat. Zanchekodden motari asat te Miramar vetat. Zankam pai asat te Campalar vetat.

Devull and igorz

Hanga ek devull ani ek igorz asa. Ponnjentle poixekar sou dis patkam kortat ani satvea disa devullant, igorjent vetat, oxem her Ponnjekaranchem mhonn’nem (korem fot, Dev zanna!). Hi gozal khori asot zalear dusri-i ek gozal titlich khori. Tea devullantli ani te igorjentli – dogui saibinni – tankam tanche guneanv bhogxitat.

Devull Mahalaxmichem. Hea devullant amorechea vellar dive lagtat. Te dive polloun Professor Borcaran ‘Tethe kor mhaze jullti’ oxi ek kovita boroili. Ani akh’khea Maharashtrak ti khub’ manouli. Ten’nachean sogli Marathi janta tankam Kovi Borcar mhonnun vollkunk lagli… Hi khobor devullachea manddapantlea sopear bosun ek Ponnjekar dusrea Ponnjekarak sangta. Ani tea vellar devullant purann cholta.

Tibluchi dairi

… atam hanv korum kitem? Mhaka vachop zomona. Chitram kaddop zomona. Kovita korop zomona. Vetam thoim lokancho kochkoch. Bovall. Laibrariank legit atam tintteanchem rup ievunk laglam. Paddpoddil’le he lok ghorcheo gozali thoim ievun kiteak kortat, hanv nokllom, bovall… bovall… bovall… Soglekodden bovall… Hanv vachpakhatir zago sodunk laglom. Kitleaxea lokamni mhaka kitleoxoch suchovnneo keleo (baki Ponnjekar suchovnneo korunk huxar!). Konn mhonnunk laglo, Campalar voch. Konn mhonnunk laglo, Miramar voch. Raibondarchea pattear… Merxeche vatter… Altineachea dongrar, mosnnant, fonddant… Sogleamni sogle zage sangle. Ek dis hanv Altinho bismache polasikoden vochun boslom. Thoim ek padri ailo. Mhonnunk laglo, hea sonvsarant soglem k-u-i.

– Mhonttokuch hanv kitem korum?

– Tum pustok vachunk hinga kiteak eilai?

– Khoi vochum tor?

– Simiterint. Tinga tuka kosloch bobav aikunk ievpacho na.

Tedischean hanv Santa Inez simiterint (mosnnant mhonnunk borem disona) vochun bosunk laglom.

Turist

Ponnjent turist khub ietat. ‘Dona Paula sundor disto’ mhonntat. Konnui muddaxekar dislear, ‘ha bogha Goveacha mannus’ mhonnun bott dakhoitat. Uprant barramnim vetat. Ani piye piye pietat.

Xinu sodanch mhonnta, hanka chorank jite marunk zai. He Mumboiche dollidri lok hanga ievun amgeli Ponnji padd ghaltat, tachem mhonn’nem. Teaporos te hippie bore. (Tanchekoddlean Xinuk bhorpur foren jinam, lugttam, goddeali, keseti bi melltat).

Simiterint Tiblu

… Atam Tibluk tanchi sonvoi zalea. Sonxebaab, Hundirmam, Bangdde Porob, Pandu Fott’to, Vitu Sawant, Xedd’do, Visvonn, Boklo, Doddearo, Vonibai, Tai-bai… sogleanchim bhutam tachekodden loktubaien uloitat.

Poir Sonxebaab boro talar ail’lo. Tibluk mhonnunk laglo, hanv tea vellar melom mhonnun suttlom. Nazalear tujechvori jivak vittlom aslom. Ponnji mhonntat ti atam sam’ki vitt ievpasarki zalea. Hanga he mosunddent tori ken’nai boro varo ieta. Bodh Purtugezanchea tempar Ponnjent golltalo toso. Toso varo ailo mhonntokuch mon sam’kem khoxi zata! Oxem dista to babddo Salazaruch sorgantsun ho varo amkam dhaddinam mum?

Sonxebaab huddkea-huddkeani roddunk laglo. Tiblu bienlo. Dolle motte korun aikot ravlo. Sonxebabak Tibluchi kakullot aili kai kitem konn zanna? Roddop tharavn thoddea vellan to mhonnunk laglo: – ‘Tiblu, papea, soglo ganv soddun tum hanga mosnnant dispotto kiteak ieta?

– Pustokam vachunk, Tiblunk biet biet zap dili.

– Pustokam vachun tum kitem kortolo?

– Mha… mhaka vhoddlo monis zavpacho asa.

– Mhojem aikotolo?

– Aikotam. Sang!

– Rajkornnant bhitor sor.

– Ani kitem korum?

– Gõycho mukhelmontri za.

– Kiteakiteim kitem sangta?

– Bhau mukhelmontri zalo. Tai mukhelmontri zali. Atam Babu mukhelmontri zatolo. Tea adim tum mukhelmontri za. Adim zomlem na zalear uprant za. Punn zolmant ek favt tori Gõycho mukhelmontri za ani jivitachem kalyann korun ghe! Tathastu!!

Tedischean Tiblun vachop soddlem…

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 6

Part 6 of “O concani não é dialecto do marata”, by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado,

in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2574, 17 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

The multiple, grave and fundamental divergences, both in terms of vocabulary and grammar, which we have perfunctorily examined, completely destroy the legend or fanciful assertion that Konkani is a dialect of Marathi, as its variant or phase, or as its daughter. Not even half of this would be necessary to constitute an autonomous and independent language.

It is said that against facts there are no arguments. Nor are there authorities. Unless it has something to do with past or distant events, testimony alone is of little value, if devoid of proof.

The body is there within everyone's reach. Any anatomist can dissect it, if he has the right instruments, and compare it, if he has experience and aptitude. But those who know nothing about pruning should not get into it, lest they spoil the vineyard.

It is a gross mistake to view Marathi as prototype of Konkani, or as its literary form. Such a pattern will necessarily distort the language, turning beauties into snags – as some Gongorists did in the past, with clumsy results – a monstrous amalgam. This should not be repeated in the future. With such an orientation and teachers, you can forget about cultivating Konkani. Let the language be!

Recently, it was stated that Konkani has been in existence for only about four hundred years, thus insinuating that it was a creation of the Christians. How cold-bloodedly can Goans make such audacious and paradoxical statements! Did they by any chance attend the délivrance – as they call it there, and it will not be long before they say ‘Our Lady of Bonne Délivrance’ – or at least have its birth certificate?

Prodigious Christians! They have invented a speech grammatically superior to Marathi and closer to the Prakrits and to Sanskrit!

And the amazement moves up another notch if we imagine how they imposed it on the Hindus in Goa and on the natives who went from here to as far as Bombay and Cochin, where I got to converse with a goldsmith in the said language!

Furthermore, the Hindu Brahmins who worked with Rheede on the Hortus Malabaricus (published in 1678) did not issue him a certificate in the ‘vernacular and literary’ language – Marathi – but in that monstrous Konkani; and the names that they gave to the plants were not taken from that ‘beloved daughter of Sanskrit’, but from its ‘nameless corruption’, namely: cudó, colassó, caló-dotiró, caró-nirvoló and many others. Some of them are marred by the convoluted orthography of Dutch, and the same is the case with Portuguese terms.

And the early Portuguese, who mention neither the Marathas nor their language, learned and used this gibberish, this ‘nothing’, as someone else chose to dub it, even while the country had a very developed vernacular and national language with a ‘vast and enjoyable literature’!

For example, Garcia de Orta, who spent many years in Goa, which he knew like the back of his palm, and who for his medical and botanical research took help from Kanarese (Hindu) physicians such as Malapa, writes panaj (jackfruit) and not phanaz; bibó (anacardium) and not bibá or bibbás bahó (canafistula), and not bavá or bahvá; rezanvalé (rozanvâlle), etc.

Similarly, Diogo do Couto, another Indianist di primo cartello, does not say ambá but ambó (Déc. VIII, I, 25). And António Bocarro (1635) does not say sissá, but sissó, nor does Father Francisco de Sousa (1697) employ Marathi diction when he writes charoddós.

Even the English were bewitched by this ‘unqualifiable dialect’, since it is in Konkani, and not in Marathi, that they looked for the origin of certain terms they used. Hobson-Jobson derives patamar from the Konkani, in the sense of ‘mail and vessel’: ‘In both senses the word is perhaps the Konkani path-mar, “a courier”.’ And as regards buckshaw, mentioned by Fryer, Hamilton and Grose, Yule writes: ‘“Little fish of any sort.” This is perhaps the real word’. Clearly, there are Konkani dictionaries that, in the opinion of the foreigners, deserve to be perused. And our scholars do not bother to read them, because they are not ‘comme il faut’. Good pretext for lazybones, no doubt: Language, why do I want you?

The last of the abovementioned words is indeed registered without its etymology, in my dictionary, under the forms bavxem and bapxem, and meaning ‘small fish, minnow’. But there will be always be a Konkanist emeritus who will declare that such a word does not exist, because he has not heard it, and that the dictionary is worthless. Jesus Christ forgot to include among the beatitudes: Beati ignari, qui sapientes se ostendunt! It is always more elegant to be a master than a disciple; it is more comfortable to teach than to learn.

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 5B

Part 5[B] of “O concani não é dialecto do marata”, by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado,

in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2573, 16 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

There is a lot more to dig in this rich mine. I believe, however, that what has been laid out here is sufficient to understand the conjugational relations between the two languages. For sure, they are not very close. And so much of Konkani’s baggage definitely would not fit into the Marathi boat. It may have got bigger later, but surely Konkani was not the poorer for it; it rather got perceptibly richer.

Even so, given its special importance, let us analyse the Indo-European verb as (Sansk.) or es (Lat., es-se for es-re), to be, to have.

Sanskrit: Asmi, asi, asti, smas, stha, santí.

Konkani: âsám, âsáy, âsá (asa, among the Hindus), âsámv, âsát, âsát. Abbreviated form: âhám, hâháy, âhá, etc.

Marathi: âhe, âhes, âhe, âhom, âhám, âhet.

It is obvious that the anomalous flexions of Marathi would not produce those of Konkani, which are entirely regular, affixed to the root (as in Sanskrit), without the intervening suffix t (sart-t).

The past tense in Konkani uses the base as: âslom, âsloy, etc. That of Marathi is: hotom, hotás, hotá, etc. That is a huge difference – toto coelo – and does not discredit Konkani.

Another Sanskrit verb, jan (3rd p. pres., jâyate), to turn, to become, to get (French, devenir) passed on to Konkani in the stem zá (zátam, zátáy, zâtá), and is conjugated regularly in all tenses. Marathi, on the other hand, uses the said verb only in the past tense (jhâlom), replacing it, in the rest, with the verb honnem, derived from the Sanskrit bhû, which has given rise to the Lat. fu-i.

It is obvious, then, that these are not despicable minutiae that can be easily explained as ‘the degeneration of Konkani taken to extremes.’ On the contrary, they are fundamental divergences, and the aforementioned verbs are so too. It is rightly said in Konkani, when one hears nonsense: Tujé jibek hadd na munn borem âsá: You’re lucky that you don't have a bone in your tongue, or else it would break. And another popular saying goes as follows: Tuka jib nasli zâlyár kavlle tonchún kâtelé âslé: if you had no tongue (the only sign of life), crows would peck and eat you (as if you were a corpse).

Let us also compare the flexions of the same substantive verb to be in the Romance languages, so that the comparison highlights the inconsistency of the detractors of their own language, which they have never cared to study.

Latin: Sum, es, est, sumus, estis, sunt.

Portuguese: Sou, (archaic som, sam), és, é, somos, sois, são (archaic, som) [I am; thou art; he/she/it is; we are; ye/you are; they are]

Castillian: Soy, eres, es, somos, sois, son.

Italian: Sono, sel, è, siamo, siete, sono.

French: Suis, es, est, sommes, êtes, sont.

Is there less affinity between these flexions than between the previous ones? And yet, to this day no one has dared claim that one of the said languages is a corruption of the other. And according to an English proverb (may everything pay homage to the alliance!): What’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander.

Let us now compare the negative forms of the aforementioned verb as:

Konkani: Hámv nám, túm námy, tó nám, ámím nâhv, tumim nánt, té nánt.

Marathi: Mîm nâhîm, túm nâhíms, to nâhím, âhmí nâhim, tuhmi nâhim, te nâhínt.

The Konkani verb záy, often used in the sense of the Latin oportet, it is necessary, it is proper, is invariable and mimics the Latin construction: Mâká záy, tuká záy, táká záy, etc. Mâká zây zataló = it will be necessary for me. Mâká záy zâló = it was necessary for me.

Marathi uses pâhije, which they conjugate as follows: pâhije, pâhijes, pâhije, pâhije, pâhije or pâhijes, pâhijet.

The verb that in both languages has the past tense in gelom is represented in the other tenses by means of various radicals: in Konkani, vats (hámv vetám), from the Sansk. vraj; in Marathi, zá, from the Sanskrit yá: such that in Konkani tó zâtá means ‘he becomes’, and in Marathi to zâto means ‘he goes.’

The irregular Marathi past tenses of certain verbs are used, partly by some social classes of Goa, but not by the Brahmins, who use it otherwise: Ghetlem = ghelem (regular), was taken; dhutlem = dhulem (reg.), was washed; pyâlem = piyelem or pilem (reg.), was drunk; mâgitlem = mâglem (reg.), was asked for[i]; ghâtlem = ghâlem (reg.), was put; mhanttlem = mhannlem (reg.) or mhullem (by assimilation), [was said]; khâllem = khelem (khâlem would be regular), was eaten.

I could have expanded on this arid and, for many, boring matter, tackling particles and syntax, but I think it is pointless. As regards the former, it will suffice to note that many of them differ from language to language or take diverse forms. Some of them in Marathi are used only by certain classes in Goa; which may be due to ethnic relations. It is a matter more closely associated with lexicology than with grammar; and the comparison is not tough.

Properly speaking, the syntax of modern Indo-Aryan languages has few essential differences. Sentence construction and agreement are almost the same. However, Marathi and Konkani vary a lot in the manner of forming propositions; in ‘our language’, it is more concise, cohesive and elliptical. Here are some examples, taken from Navalcar's Marathi grammar: Râma ânni tyâtsá bâp âle âhet = Râmá âni tâtsó bâpúi áylé: Rama and his father have come. Durgá ânni Sâvitri hyâ bahinni hotyá = Durgá áni Sâvitri bahinnyó: Durga and Savitri are sisters. Janoji va tyâchi báyko kutthem gelim âhet = Janoji âní tâchî bâyl khaim gelint? Where have Janoji and his wife gone? Vaidyânem tilá auxadh deún barem kelem = Vaizan tiká okhat diún bari keli (agreement difference): The doctor cured her by giving her medicine. Mim tum’chyá gharim udyám yein = Hámv tum’ger phalyá yen or yeyn (I may come) or yetalom = I shall come: I shall come to your house tomorrow.

Those interested can easily make other syntactical comparisons, for example, between a catechism in Konkani and Marathi. Rest assured that one will learn a lot about the disparity of the two languages and be convinced – if any more arguments are necessary – that Konkani is not the same as Marathi.

-o-o-o-

[i] Dalgado’s says ‘foi bebido’, which is obviously a typo; it should read ‘foi pedido’ [was asked].

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 27, March-April 2024, pp 38-41)

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 5A

Part 5[A] of “O concani não é dialecto do marata”, by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado,

in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2572, 15 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

If, however, lexicology does not suffice, let us look at grammar, which better characterises a language and provides a safer criterion.

As regards phonology, it is obvious to whoever has some notion of Konkani and Marathi phonetics that the former, besides employing all the phonemes of the latter, has some unique ones, such as open é and ó, which distinguish words, genders and numbers. Pêr (fem.), guava tree, and pér (neut.), guava; pêr (fem.), roe, pér (neut.), finger joint. Bôr (f.), jujube tree, bór (n.), jujube. Pôr (m.), lad, pór (pl.), lads, (n.), girl. Môr, peacock, mór, peacocks.

The tonic e of masculine nouns also develops into diphthong eu (very faint u): euk, êk, ék, one, one, veull (m.), time, vêll (f.), beach, véll (n.), pick, kheull, game, meull, dirt.

The short a deserves special mention; it is close to the muffled and short o, as in Bengali, or better, as in the English u in but, cut.

It also has another notable peculiarity: that of being, like the open and closed o, contingent on the genders. The a of bhirandd, mangosteen tree, and the a of bhirandd, mangosteen, are not pronounced identically, except perhaps by a child in diapers. Also compare the second a of kharadd (f.), shavings, with that of kharadd (n.), bald head; that of karadd (f.), dryness of tongue, with that of karadd (n.), grass. Those who fail to understand this may be capable of speaking the Bunda language, which does not require great expertise, but they certainly do not understand the phonics techniques of Konkani. It is said that honey is not meant for the ass’s mouth.

Similar to the pre-consonantic tonic e of masculine nouns, the long á of certain feminine nouns develops into a regressive diphthong eá (or yá) with muffled e: sattyá = Sansk. sattá, authority. Tarhyá = Mar. tarhá, from the Arabic tarhá, type, manner.

The ch and j, when not preceding e and i, always sound ts (or tç) and z, without etymological restrictions; which is not the case with Marathi. Sansk. chal = tsal, go; char = tsar, folder; chakra = tsak, wheel; Râjâ = rázá, king; jana = zann, person; jati = zát, caste. People observe the logical coherence instinctively and send the etymologists packing. But in our eccentric Goa there are philological heavyweights armed with a ferule: they disregard such a clear truth! Or else, they would not be pinchbeck scholars nor would they be acclaimed by puppets.

Furthermore, the initial h and the h of aspirated consonants is not as sonorous as in Marathi, and many of the Marathi cacuminal initials correspond to the respective dentals in Konkani.

Can all these peculiarities be borne out by the evolutionary process or, if unscientific detractors so wish, by later corruption? And how is it that identical phenomena are unheard of in other Marathi areas? And will not at least such elements be useful to establish the autonomy of a language?

With regard to morphology: if there was anyone who, comparing the declensions and conjugations of Konkani and Marathi, has found complete uniformity, he was blind in spirit. The multiple and grave discrepancies are, as the English say, glaring; they stand out and can do without the lantern of Diogenes.

The long á of the nouns and adjectives in Marathi (as well as Hindi) corresponds in Konkani to open ó (closed ô in Gujarati and Sindhi). Goddá = ghoddó, horse; pâddá = pâddó, bull; reddá = reddó, buffalo; dhava = dhavó, white; kallá = kâlló, black.

Now, Sanskrit has never had the nominative singular in long â of the nouns ending in a vowel, except for vocalic r, which, really speaking, is a softening of ar (pitr = pitar; cf. Lat. pater). But under certain circumstances, the desinential visarga changes to ô. Axvah patati, the horse falls; axvo gachchhati, the horse goes. Gajah sarati, the elephant moves; gajo mritah, the elephant died. Xukla puruxah, white man; xuklo manuxyah, white man. Similarly, in ancient Prakrit we see the nominative in ó: Sansk. prasaráh, Prak. pasró, Konk. pasró, shop; pânddurah (whitish), panddrô, pânddrô, king cobra; devarah, devarô, dêr, brother-in-law. Konkani is not in bad company.

The same difference between á and ó is seen in masculine genitive terminations: âmbyáchá = âmbyatsó, of the mango, – in the nominative plural of feminine nouns (ô): gaddyá = gaddyô, cars; and in the verbs (3rd person) (sing., perf. indicative) utthlá = utthló, stood up.

The terminations nem and xim of the Marathi instrumental correspond to n in Konkani, and to lá and s of the dative, k (ko in Hindi, ke in Bengali): âmbyânem (by the mango), âmbyâxim (with the mango) = âmbyan (with or by the mango); âmbyálá or âmbyas, âmbyak (to the mango).

The terminations of the nominative plural of neuter nouns also differ: motyem = motyám, pearls; gharem = gharám, houses.

Konkani has a formal locative on, which Marathi represents periphrastically: mathyár = mátyá var, on top of the head; gharámr = gharám upari, on the housetops.

There are nouns that have one base or theme in Konkani and another in Marathi = hatti (dental tt) = hattyán = háttinem, by the elephant; bhint = bhintyechí = bhintichi, of the wall; khâtt = khâttichem = khâttechem, of the bed.

We have already seen that the nominative and the instrumental of the first-person pronoun are not the same in both languages. Let us now compare other cases and other pronouns. Dative. Mâká (cf. Sansk. mayam, Lat. mihi, which is sometimes pronounced as miki) = mâlá, to me; âm’kám = âhmâlá, to us. Tuka, tulá, tujlá, to you; tum’kam = tuhmâlá, to ye/you. Tâká or teká = tyâlá, to him, etc. Instrumental: tuvem = tvá, for you. Tannêm, tínnem = tyannêm, tinem, by him, by her. The same is to be said of the demonstrative hó, this, and the relative zó, that: hâká, zâká, hânnem, zânnem.

The conjugational differences between the two languages are so many that I do not know how to deal with them in a few words. It would be necessary to reproduce entire paradigms of various verbs to help one get a complete idea. Those who feign ignorance, and those who consider themselves all-knowing, will stay put; those who sincerely wish to study will find half a dozen grammars. But there are some people out there who swear by all gods that Konkani has no grammars and dictionaries comme il faut! Might they have examined them all? And are there many Marathi-Portuguese dictionaries, and vice-versa, and grammars comme il faut? The English put it nicely: ‘Fools rush in where the wise fear to tread.’

I will nevertheless present some corroborative schema as specimens.

Radical sar, to go, pass. Sansk. Sarâmi, sarasi, sarati, sarâmas, saratha, saranti.

Konk. Hámv sartám, tum sartây, tó sartá, ámim sartam, tumim sartát, té sartát.

Mar. Mim sartom, tum sartos, to sarto (m.); mim sartem, tum sartes, ti sarte (f.) mim sartem, tum sartem, tem sartem, (n.) Pl. âhmi sartom, tummi sartám, te sartát.

Lat. Amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, amant.

Port. Amo, amas, ama, amamos, amais, amam. [I love, thou lovest, he/she/it loves, we love, ye/you love, they love]

Cast. Amo, amas, ama, amamos, amais, amam.

Ital. Amo, ami, ama, amiamo, amate, amano.

Now, is there not a closer analogy between the flexions of the Romance languages than between those of Marathi and Konkani? And yet there are sharp minds that do not realise it.

Let us juxtapose Sanskrit and Latin flexions. Radical vah-veh: vahâmi = veho, vahasi = vehis, vahati = vehit, vahámas = vehimus, vahatha = vehitis, vahanti = vehunt. Are not these flexions more akin to each other than are those of Konkani and Marathi? Might Latin, then, be a corruption of Sanskrit? There are no people more exacting than the Goans.

Past perfect. Konk.: Hámv sarlom, túm sarloy, tó sarló (m.), hámv sarlim, túm sarliyi, ti sarli (f.), hámv sarlem, túm sarlemy, tem sarlem.

Mar. Mim sarlom, túm sarlas, to sarlá (m.), mim sarlem, tum sarlis, ti sarli (f.), mim sarlem, túm sarlens (n.) Is the daughter a faithful likeness of the mother?

Imperfect: Konk. Sarom, saroy, saro, saromy, sarot, sarot. Mar. sarem, sares, sare, sarúm, saram, sarat.

Konkani has another formal imperfect, made up of the base of the present tense and the flexions of the perfect; and that has no counterpart in the other language: sartâlom, sartaloy, sartâló (m.), sartalim, sartâliy, sartáli, etc.

At the same time, the past perfect, formed by adding ló to the perfect: sarló, it ended; sarloló, it had ended.

Future. Konk.: saran, sarxi, sarat, sarâmv, sarxyát, sartit. Mar.: saren, sarxil, sarel, sarúm, saral, sartil.

How much parity is there between one and the other?

The aforesaid Konkani future is contingent (as Maffei calls it, if you know) or potential: karít, may be able to do it, may wish to do it, maybe doing it, may do it; páus paddat, it may rain, perhaps it will rain. But we have another future, absolute and more assertive, which in Portuguese is expressed as há de [will]: há de chover [it will rain], which differs from choverá [it will rain].[i] Marathi does not have it in a simple form; Konkani, on the contrary, forms it with the flexions of the past tense joined to the base of the present, ending in a (sarta), or to the present participle (sartó): sartalom, sartaloy, sartaló, etc.

-o-o-o-

[i] Both Há de chover and choverá express the future tense, except that that the former is in the periphrastic form.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 27, March-April 2024, pp 38-41)

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - IV

Part 4 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata", by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2571, 14 February 1917, p. 1

Translated from the Portuguese by Óscar de Noronha

IV

I now ask: does Marathi provide an explanation for the lexicon and grammar of Konkani, as we have known it since times immemorial? Let us take a look.

Words are generally migratory. They accompany the objects that they designate, and they connect easily from one language to another, even if unrelated. See my book Influência do Vocabulário Português for the number of Portuguese expressions and how many Asian languages that they got into.

Nor is there any European language devoid of pilgrim or heterogeneous terms. And Marathi itself, which seeks to stand on a pedestal, is full of exoticisms of different origins, as can be seen from any etymological publication. It even uses Portuguese expressions that are not in vogue in Goa, such as tabaco (tobacco), tronco (jail), ripa (lath), armada (armada), barqueta (small boat), barquinha (scull). And Sanskrit has the Greek horá, the Latin dinaro and the Semitic kulama.

But the words that serve as yardstick for languages to relate or to delimit themselves are not such as to be regarded as adventitious or ambulant. On the contrary, they are considered organic and basic.

Such words concern the first elements, family relationships, religion, pronouns, names and numbers, main verbs, all of which form the structure. And this was the pattern that shaped the genealogical tree of the Indo-European group and established their mutual relationships.

Now, Konkani has many terms of this kind of primary necessity and of common usage, deriving from Prakrit (bâlabhâxa) or from Sanskrit, terms that it did not receive through the intermediacy of Marathi, for the simple reason that the latter does not know them or make use of them in colloquial speech: nemo dat quod non habet.

Gerson da Cunha mentions one pronoun and eight nouns in Konkani, besides verbs and adverbs in vogue, which are not commonplace in Marathi. They are ahum (I), pârvó (pigeon), kîr (parrot), bokem (crane), sunem (dog), zang (thigh), poló (face), kankon (bracelet), râzû (cord).[1] And he notes: "Several more (words), the identity whereof with Sanskrit can be easily verified, are not in use among the Marathas."

Ramchandra Gunjikar, however, collects dozens of expressions derived from Sanskrit, which are not found in Marathi, or have some different forms. I find it inconvenient to reproduce them; but the scholar will be able to check them out at their source, and will not find it a waste of time. I will restrict myself to a few that seem to me important and peremptory.

It is well known that the Indo-European group has thematically distinguished the direct (nominative) case of the 1st person pronoun from its oblique cases, as in the Greek and Latin ego, Sanskrit aham, and the other branches. The word corresponding to ahum is ham in Prakrit and hâmv in Konkani, which in the instrumental case assumes the form hâmvêm. In Marathi, the first case is represented by mim and the second by mya or mim. How is this possible, if Konkani is the daughter or corruption of Marathi? Note that this point is partly morphological, and this enhances its value.

| Sanskrit | Prakrit | Konkani | Marathi | |

| Son | putra | puttaka | pút | mulgá |

| Daughter | duhitá | dhiyá | dhúv | mulgi |

| Son (restricted) | chetta | chelá | tsaló | mulgá |

| Boy | chetta | … | heddó | mulgá |

| Water | udaka | udaka | udak | pânni |

| Fire | vidyut | vijjú | uzó | vistú |

| Summer | grîsma | gihma | gim’ | ubnállá |

| Tree | vrikxa | rukko | rukh | jhádd |

| Hay | trinna | tanna | tann | gavat |

| Ash | goma a | … | gobar | rákh |

| Step | sopâna | sopânn | sopann | pâyri |

| Column | stambha | khambho | khâmbó | khâmb |

| Hair parting | mârga | maggo | mâgo | bhàng |

| Road | mârga | maggo | mârag | rastá |

| Toddy | surá | sura | súr | tâddi |

| Jackfruit | panasa | panasa | pannas | phannas |

| Big | vriddha | vudhdho | vhadd | motthá |

| Frontier | samukha | samukho | sam’ko | samor |

| Much | bahu | bahu | bah | bahut |

| Be | jâ (ya) | … | za | ho |

| Go | vraja | vachcha | vats | zá |

| Take | hara | … | vhar | ne |

| Call | âhvaya | âbaya | âpay | loláv |

| Place | dhara | … | davar | tthey |

| No | na | … | ná nâm | nâhim |

| Inside | abhyantar | … | bhitar | ânt |

| What? | kim tad | … | kitem | káy |

| Where? | kva | … | khaim | kottem |

From this example it is clear what kind of mother Marathi might be to Konkani. And to think that there are Konkaniphobes who platonically bemoan the bastardization of their language, which they do not seek to learn! It is said in Konkani that whoever cannot dance blames the unevenness of the floor: nâtsunk nennó, ângann vânkddem.

There are many terms specific to each language, deriving from different sources, which terms occur frequently, given that they represent commonplace ideas. Here is a small specimen:

| English | Konkani | Marathi |

| Habit | vaz | savaí |

| Love | mog | príti |

| Bride | hokal | navari |

| Fan | âllnnó | pankhá |

| Palm-tree leaf | tsuddet | zhâmpem |

| Resentment | xínn | rusvá |

| Heel | khott | lát |

| Ant | múi | mungí |

| Lie | phott | gapp |

| Cloth | kâpadd | lugddem |

| Broom | sarann | kersunní |

| Orchard | kullâgar | bág |

| Monkey | khetem | mâkadd |

| Auction | pâvnní | lilâmv |

| All night | savandrat | râtrbhar |

| Tomorrow | phâlyá | udyám |

| Nearby | lâgim | zavall |

| Far | pais | dúr |

| Before | âdim | pûrvim |

| After | mâgir | mag |

| Presently | sardyá | turt |

| Behind | pâthi | mágem |

| Below | saklá | khálim |

| Gold | bhángar | sonem |

| Egg | tântim | anddem |

| Money | duddú | paisá |

| Stick | boddí | kâtthí |

| Limit | mer | maryâd |

| Writing | barap | lekh |

| Write | baray | lihí |

It would be a never-ending story. But it will also enable unsuspecting minds to assess the nature of the Konkani vocabulary and its relations with that of Marathi, especially if they take into account that many of the expressions common to both languages exist in other Neo-Aryan languages too, for they come from the ancient Prakrit languages. And they should not lose sight of the fact that those who, guided by analogies, consider Konkani to be a dialect of Marathi, will take words of the former as belonging to the latter, when dealing with its lexicon and grammar, as Dr Bhandarkar has done in his learned book Wilson Philological Lectures.

They will also note from the Kannada terms, marked with asterisks, how deep pilgrim expressions can penetrate, and supplant the previous homogeneous ones, on account of vicinity, conquest or trade. And they will not be surprised that the Portuguese language has contributed a large corpus, even if partly unnecessary. And likewise, Marathi has been taking many English words, as it did with Persian and Arabic. Such is the fate of the conquered.

Whoever is interested in more etymological information may look up my dictionary, where the origin of each word has been very diligently sought.

There will, however, be no lack of freshwater Konkanists who will continue to assert from their perches that none has understood the Konkani used in my dictionary, and that therein is not the Konkani that they speak. But would they know how to read it properly and do they have great knowledge of the language? A boorish Portuguese or Frenchman contented with some three hundred words, will obviously not understand a dictionary like that of Domingos Vieira and of Cândido de Figueiredo or those of Littré and Larousse. And how many Marathists are familiar with all the words mentioned by Molesworth and Candy? Those who do not know must learn and not preach.

Perhaps they think that I toured the lunar regions to put together the dictionary. Fortunately, many of those who witnessed its compilation are still alive and can vouch for the care I took to collect words and phrases, and the criterion that determined their inclusion. Imperfections it has aplenty, and they were unavoidable, given the circumstances. A perfect dictionary of living languages is nowhere to be found. Nor was it made for the blind in spirit who presume to be hawk-eyed. Others pronounce the dictionary to be more of Marathi than Konkani. So be it, for till date there is neither a Marathi-Portuguese nor a Portuguese-Marathi dictionary available, while Konkani has some old and modern ones. Our great Marathist Suriagi was at the most able to translate, but alas, very poorly, the dictionary by Molesworth – a Christian and European, two grounds of incapacity for Orientalism, in the opinion of our young Turks – and he only managed to have a part of it published. But why Marathi? For inserting many words that exist in Marathi? And would the Marathi dictionary be Sanskrit or Hindustani because it includes numerous words from those languages? Or will Phondu Sawant’s durai (ban) weigh on Konkani, in that no pilgrim expression be admitted without his prior sicó (stamp)? How far can disoriented passion or petulant ignorance get!

So, as for me and some others, many of the words that Marathi dictionaries claim as being in use in the Konkan, in Sawantvadi and Malwan, and even in Ratnagiri, owe their paternity to Konkani. Just as Hindus who know Marathi fit various words of this language into Konkani, so do Hindus originally from Goa introduce Konkani expressions into Marathi.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 26, Jan-Feb 2024, pp 16-20)

[1] Spellings taken from Dalgado’s article, slightly at variance with Gerson da Cunha’s. (Translator)

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 3

Part 3 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata", by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2570, 13 February 1917, p. 1)

III

Since Konkani is not a dialectal variant of Marathi, would it at least be a dialect, in the sense that it originated from the Marathi in ancient times?

It seems that for expert philologists there, the assertion is almost an axiom, which admits of no discussion. There are writers who declare it; there are Marathists who swear by it; there are many obvious analogies between one speech and the other. What more can one want?

But there are also many analogies between Gujarati and Marathi. Therefore, one is a dialect of the other! There are many points of contact between Portuguese and Italian. Therefore, one has derived from the other! There is almost no Arabic word that is not used or cannot be used in Persian. Therefore, both languages belong to the same family, Semitic or Aryan! Konkani also seems to have similarities with Gujarati, Hindi, Sindhi, Bengali, Oriya, Punjabi, Kashmiri. Therefore, it is a daughter of them all! I do not know if it was for this reason that someone has said that she is almost a “daughter of Marathi”, or if because she has not yet fully emerged from her mother's womb.

It would in fact be surprising if there were no similarities between the sister languages; they would not be from the same family. But partial similarity does not necessarily explain derivation or affiliation. Much more is needed for that. English has many French and Latin words and phrases, and nobody till date has thought of including it among the Romance languages. A language that spreads over a vast area, by absorption, colonization or conquest, naturally and unwittingly produces regional changes that can be easily understood. With the passage of time, they move away further and further from the prototype, to the point of becoming unintelligible as a whole. They then change from mere dialects to languages in their own right. However, they never substantially lose their kinship with the mother language or with others of the same origin. They are like water flowing from the same source by different channels.

But it is one thing to be a sister and another to be a mother; what is good enough for the former is not good enough for the latter. Sisters are content with the broad strokes; a daughter demands that the mother give a reason for her existence.

In the first ardour of enthusiasm, produced by the discovery of Sanskrit by the Europeans, it was believed that the said language was the mother of Greek, Latin and others languages of Europe. But soon it was found that it did not satisfactorily explain the phonology and morphology of like languages, which had phonemes (short e and o) and more primitive forms. It was then acknowledged that only the elder sister had the key to the resolution of various linguistic problems. And it was concluded that there might be another language without historical monuments from which Sanskrit, Iranian, Greek, Latin, Celtic, etc. have derived. The existence of the Indo-European or Proto-Aryan is now an established and inescapable point, by the principle of causality.

I have no doubt that this is Greek to several of my enlightened countrymen. A Sanskrit scholar asked me how one might explain the opposition by the Hindus of Goa (whose progress has of late been praised) to the introduction of the Sanskrit chair at the Goa Lyceum, whereas they should have been more committed! I had to contend with regret that the real reason would be the fallacy or patravôll of the Marathi chair, and the opponents some kind of young Turks who try to jump, as they say in Konkani, over the herb plants: tsannyânchím jhâdám uddunk. For I have always regarded the Hindus as staid people, and I would not ascribe to them such foolishness.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 25, Nov-Dec 2023, pp. ___)