What was the Inquisition? - 3

Even though it was a webinar relating to the Goa Inquisition that acted as bait, the purpose of this three-part series has been to study the concept, origin and development of the Inquisition in general, since those who malign it hardly care to understand its rationale.

By way of recapitulation, we could say that, with Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire since the days of Constantine, Church and State worked closely together. Unity of faith was essential not only to the ecclesiastical organization but to civil society. Although both Church and State had their own sets of laws their jurisdictions overlapped at times. Some ancient laws and procedures were Christianised, to the extent that the monarchs consented; the high and mighty had their own ways and very often even overpowered their spiritual head, the Pope.

Ultimately, in the sixteenth century, Church and State reached the tipping point in terms of jurisdiction. Pope Gregory IX decided to shoulder a task that had long been in the secular domain. He instituted a full-fledged inquisition tribunal to conduct official inquiries into heretical behaviour of Catholics, the intention being more reformative than punitive. While the tribunal dealt with what was essentially a spiritual issue, punishment for the recalcitrant remained a domain of the State, considering that heresy was a crime on a par with high treason.

Confused Perspectives

If the Inquisition is a scandal to non-Catholics, an embarrassment to Catholics in particular, and a pretty confusing thing to all, we hope that in tackling the confusion here, some of that scandal and embarrassment too will be resolved.

Behind a state of confusion there often lurks a malicious resolve to confuse. The webinar organised by a national-level Hindu fundamentalist outfit, on 30 May 2020, was a harangue spewing venomous myths to fuel the public imagination. The Upanishadic “Satyameva jayate” (Truth alone triumphs) went out of the window; it may require another series on the Goa Inquisition alone to restore the truth, or we could wait for the panelists to return after some homework.

There is also confusion when history is critiqued from a modern standpoint. As expected, in a post-webinar engagement, a “presentist” decried the Inquisition as a violation of human rights! Well, why just the Inquisition? By our standards, many ancient legal procedures would be dubbed unjust, surgical methods barbaric and disciplinary methods cruel! In the frenzied context of the pulling down of statues, probably every wonder of the world would have to be flattened for failing to measure up to our benchmarks of social justice.

On the other hand, it is interesting to note that even though medieval society did not look at “human rights” the way we do, the natural law discourse was active; it evolved into “natural rights” in the so-called “Age of Enlightenment” and emerged as “human rights” in the twentieth century. Our difficulty in appreciating the evolution shouldn’t make us flag-bearers of ingratitude lest we fail to acknowledge that, under that very same code of ethics, there was progress in art, science, culture and commerce, of which we are beneficiaries.

At any rate, the black legend surrounding the Inquisition is not of recent origin. It began with the Protestant Revolution and continued through the French Revolution and the Liberal revolutions in Europe. Even in the midst of all that radicalism, Voltaire, an arch-enemy of the Catholic Church, had the composure to write: “You have to be very cunning to calumniate the Inquisition, and to look for lies to render it odious.” Protestant authors like Henry Charles Lea and G. G. Coulton probably got most of the facts right but failed to weigh them well, perhaps influenced by prior animosity toward the Catholic Church (though not to the Inquisition itself) and/or overwhelmed by the subject. And somewhat similar was the sensational tale of the Goa Inquisition as told by a culprit (Charles Dellon), full of sound and fury – signifying something, for sure; but generations handled it sloppily, wickedly, and blew it out of proportion.

Artists and philosophers too added fuel to the fire. Some of the confusion surrounding the Inquisition came from their symbolic or fictional accounts. For instance, “St Dominic presiding at an auto da fé”, by the Spanish Pedro Berruguete, showed all stages of the Inquisition as happening at once, as though it were a free-for-all; of Dostoevsky’s poem “The Grand Inquisitor”, in The Brothers Karamazov. The illustrations in Dellon’s book too are fictional and deceptive. Likewise, the large numbers of burnings detailed in some historical accounts are unauthenticated, possibly the invention of pamphleteers.

Needless to say, serious authors across the world have treated the subject of the Inquisition in an unbiased manner, calling the spade a spade; but they haven’t been dramatic enough to garner attention.

Scandalous, is it?

Was the very inquisitorial method a scandal? It is one of the two types of legal traditions that have dominated the nature of investigation and adjudication around the world, the other being the adversarial system. The Church had no option but to follow the Roman Empire’s ‘civil law’ tradition which prescribed the inquisitorial system (as opposed to the ‘common law’ system followed in some other parts of the world).

While in the adversarial system, the prosecution and defence are said to compete against each other, with the judge serving as a referee; the inquisitorial system is characterized by extensive pre-trial investigation and interrogations aimed to avoid bringing an innocent person to trial. The judge here has relatively more powers but he is not ipso facto an enemy of the accused. In fact, with lawyers averse to arguing the case of a heretic, the inquisitor had to steer the collation and prepare the evidence, while all the while coaxing the suspect into owning up and returning to the fold.

The use of torture as a means of obtaining confessions is also contentious. It was generally opposed by the Catholic Church through the Early Middle Ages; however, in the High Middle Ages, the Church, extremely preoccupied as it was with the great threat posed by mushrooming heresies, Catharism in particular, adopted the torture methods employed by the secular governments. Pope Innocent IV, in Bull Ad extirpanda (A.D. 1252), stipulated that the inquisitors were to “stop short of danger to life or limb”; but alas, there was scope for abuses, and the accused could well have endured the torments without admitting anything, or admitted guilt of a crime not committed.

Finally, what of the death penalty and the concurrent confiscation of property? While many learned churchmen had found burning at the stake incompatible with the spirit of Christianity, the civil authorities were bound in duty to apply the punishment. While confiscation of property added insult to injury, the provision was designed to snuff out the family’s tendency to spread the heresy with a vengeance. Some allege that confiscations brought in revenue, but then, not all convicts were rich, and the proceeds were anyway meant for the upkeep of the court.

In those days scarcely any community or nation would tolerate the setting up of a creed different from the majoritarian creed. To put this historical fact in perspective, it is imperative to note what was done by those who left the Catholic Church, advocating private judgment and criticising the Inquisition: the pseudo-Reformers Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and their adherents, in turn were prompt in using torture against those who differed from them in matters of belief. In the sixteenth century, thousands of non-Anglicans were killed in England at the behest of King Henry VIII; in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the American Puritans conducted inquisitions and burnings at the stake. The practice continued long after the pseudo-Reformation. The French Revolution, and the Mexican and Russian revolutions at the beginning of the twentieth century, had summary executions galore.

A redeeming feature of the Inquisition was that it closed the era of summary executions and considerably reduced death penalty sentences. As stated by Henry Charles Lea, in A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages, “however much we may deprecate the means used for its suppression [of heresy] and commiserate those who suffered for conscience’ sake, we cannot but admit that the cause of orthodoxy was in this case the cause of progress and civilization.” He stressed that “the Inquisition was not an organization arbitrarily devised and imposed upon the judicial system of Christendom by the ambition or fanaticism of the Church. It was rather a natural – one may almost say an inevitable – evolution of the forces at work in the thirteenth century, and no one can rightly appreciate the process of its development and the results of its activity without a somewhat minute consideration of the factors controlling the minds and souls of men during the ages which laid the foundation of modern civilization.”

Bernard Shaw put it down very categorically: “… Nobody thinks of these liquidations [of lower animals] as punishments, nor expiations, nor sacrifices, nor anything but what they really are: sheer necessities. Precisely the same necessity arises in the daily-occurring cases of incorrigibly mischievous human beings. They are vermin in the commonwealth, ferocious wild beasts on our highways, robbers and crooks of all sorts.”

What’s the scene in the early twenty-first century? Thirty per cent of the countries under the United Nations have retained capital punishment, and some have extended its scope. Iran, Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and the Philippines, to name a few, impose a death sentence for importation and/or possession of drugs. Several others do so for various economic crimes, including bribery and corruption of public officials, embezzlement of public funds, currency speculation, and the theft of large sums of money. Sexual offences are also punishable similarly in about two dozen countries, including most Islamic states. China holds executions regularly for a wide variety of reasons.

Is modern society, then, any more humane than medieval society? How many consciences are pricked by the same procedures prevailing in our day and age? The inquisitorial method is still used in criminal investigation in several countries, including India; confessions are extracted under preventive detention in every region of the world; freshly devised torture instruments are rampant; protracted and expensive legal procedures in secular courts are almost a denial of justice; and, finally, the moral responsibility to decide between life and death was as great for the inquisitor then as it is now for the modern judge in countries that uphold capital punishment.

In short, the procedures of the Inquisition weren’t a denial of freedom, they rather provided protection against “freedoms” claimed by anarchists. Similarly, the death sentence wasn’t anti-life, it was a penalty imposed very sparingly, whereas some heretical groups openly advocated suicide. Finally, medieval life didn’t forbid things indiscriminately; the crazy array of anarchist groups at the Sorbonne did, with their blanket diktat “It is forbidden to forbid”…

Meanwhile, in North America, more babies die from abortion in two days than the total number of people who died during centuries of Inquisition. And euthanasia is another sordid chapter of contemporary history. These crimes against humanity will probably be recognized only half a millennium from now….

Why the embarrassment?

That is what the story of humankind has on the whole been like. Yet we seem more troubled by events that are lost in the mists of time than by our present-day evils. Does it make any sense to criticise purported crimes when we are perpetrators of real ones? Human rights, freedom of conscience, religious freedom and pluralism – haven’t they been alive and kicking for the last hundred years or so?

Catholics are therefore invited to take the bull by the horns. The Inquisition isn’t any more barbaric than wars have been; the Inquisition casts no slur on the Catholic Faith, for it was a matter of enforcing discipline, not imposing belief; the Inquisition as a tribunal is nothing to be ashamed of, for no tribunal has ever been infallible. Arguments in favour of the Inquisition valid half a millennium ago still hold true today, just that in modern times we perhaps judge differently, more leniently; but that doesn’t make the opinions held by our contemporaries objectively more correct than those held by our ancestors.

The Catholic Encyclopaedia points out that “the Inquisition, in its establishment and procedure, pertained not to the sphere of belief, but to that of discipline. The dogmatic teaching of the Church is in no way affected by the question as to whether the Inquisition was justified in its scope, or wise in its methods, or extreme in its practice. The Church established by Christ, as a perfect society, is empowered to make laws and inflict penalties for their violation. Heresy not only violates her law but strikes at her very life, unity of belief; and from the beginning the heretic had incurred all the penalties of the ecclesiastical courts.”

After all, when the welfare of the commonwealth was at stake, threatened by the anarchists of those days, why would they hesitate to sentence the same anarchists to the stake? In fact, if death penalty could be inflicted on thieves and forgers, who rob us of worldly goods, how much more deservedly on those who cheat us out of supernatural goods (namely, the Faith, the sacraments, the life of the soul)!

Modern, secular minds trained to look at the supremacy of the material world have particular difficulty in accepting the argument of the supernatural goods; but in that remote age, when the life of the spirit was given pride of place, and criminals of every hue dealt with vigorously, hatred for heresy came naturally to people. Despite that, heretics had the benefit of judicial protocol; they were not left to the dictates of an infuriated populace. The punishments, then, were an expression not only of the legislative power but also of the popular hatred for heresy.

Finally, did the Inquisition have a political motive? Yes, it did; to safeguard the polity. And didn’t they target the Jews for their money? They weren’t Jews, in the first place, but crypto-Jews, booked for heresy. With the distance of time it’s really easy to ascribe motives to events, just as in our times, many of those picked up for petty crimes in one regime were honoured as “freedom fighters” in the next – when the freedom they were seeking was nothing but licence to break the law and loot.

For all the reasons mentioned above, the Inquisition deserves neither unqualified praise nor the blind denigration it has met with. If it is the “sins” of the past that atonement is due for, it will be a long list indeed. Well, for starters, in India, let’s not forget to add and demand an apology for centuries of sati – and of untouchability, a veritable life-in-death situation!

Meanwhile, how many individuals and how many cultures can afford to be upfront as Pope John Paul II was? Addressing the International Symposium on the Inquisition, in 1998, he said: “The Inquisition belongs to a tormented phase in the history of the Church, which… Christians [should] examine in a spirit of sincerity and open-mindedness.” He added: “… before asking for forgiveness, it is necessary to know the facts exactly and to recognize the deficiencies in regard to evangelical exigencies in the cases where it is so.” In other words, we have to keep in mind “the dominant mentality in a determined area.”

Six years later, the Symposium released a report of its findings, which were based on studies of documents from the Vatican’s Secret Archives. Accordingly, most of the torture and executions attributed to the Catholic Church during the various inquisitions didn’t occur at all. In addition, the total number of accused heretics put to death during the Spanish Inquisition comprised 0.1 percent of the more than 40,000 who were tried. The number of witches burned at the stake by the inquisitions in Spain, Italy and Portugal was 99, out of more than 125,000 trials. In fact, in some cases the inquisitions saved lives by saving accused heretics from secular authorities, who had both the power and desire to execute them.

Were the Church authorities, then, pressurised by internal and external agencies to tender that apology, to appease a brave new, multi-cultural world? Be that as it may, the Pope quite magnanimously refrained from demanding apologies from other religious, political or social agencies for their many acts of commission and omission. Regrettably, those illuminating research findings came after the apology, which had meanwhile put the Catholics on the back foot. The need of the hour was (and still is) to enlighten – or rather, counter-enlighten – the faithful on what the historical Tribunal really stood for. Quite ironically, in recent times, this omission alone – more than all that criticism from adversaries or ignoramuses – was responsible for making the Inquisition look monstrous.

29th June 2020, Solemnity of SS Peter and Paul. Both died for the Faith, crucified upside down and beheaded, respectively, under Roman Emperor Nero, between A. D. 64-67.

(Concluded)

What was the Inquisition? - 2

Considering that the secular mind is quick to make the very word ‘Inquisition’ look odious, is it not its bounden duty to also check its own moral standards? Can our generation be sure that future generations will not be as uncharitable towards us as we have been vis-à-vis the Inquisition?

It is only fair that an institution or an event be looked at in the light of its age. Hence, before we draw up a balance sheet of the Inquisition, let’s look at some of its features. When the medieval institution was eventually replicated in many countries, there were inevitable changes in its set-up from place to place; however, its nature and procedures remained essentially the same, as outlined below.

Features of the tribunal

a) Nature: Ecclesiastical courts dealt regularly with disputes concerning discipline, administration of the church, and spiritual matters. But in places where heretics were strongly entrenched, the Church set up the inquisition as a special court with permanent judges or inquisitors. It was a formal court with rules of canonical procedure; its judges executed doctrinal functions in the name of the Pope. Thus, the Congregation of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition, or Holy Office, established in Rome in 1542 was historically continuous with the episcopal courts of earlier times and with the ones set up later. In the age of liberalism the powers of the tribunal came to be limited by local control and resistance.

At establishment of the inquisition in the thirteenth century, members of the Dominican and Franciscan Religious Orders, newly set up then, were offered the inquisitorial task, in view of their superior theological training. There is no reason to believe that those judges were in any way intellectually and morally inferior to their counterparts in modern judicial tribunals. Some inquisitors were no doubt harsh; but their lot has to be judged as a whole. Some errant inquisitors were even deposed and then incarcerated for life.

b) Procedure: Any new inquisition tribunal began by declaring a “period of grace” for the local Catholics. When summoned before the inquisitor, those who confessed their faults of their own accord were given a mild penance. When suspects did not report, and meanwhile much evidence had been obtained against them through the parish priest or lay persons, such suspects were cited before the judges and the trial began. If they made a clean breast of their faults, the affair was soon concluded to the advantage of the accused. If they entered denial even after swearing on the Gospels, the evidence already collected was put forward.

It is not known for sure whether the accused were imprisoned throughout the period of judicial inquiry. It seems quite unlikely that they would be, considering the burden on the exchequer. Nor was it even necessary, for freedom of movement was conditional: the suspect had to promise under oath to be available for inquiry and to accept the inquisitor’s sentence with good grace. Obviously, the judge would be favourably inclined if the suspect kept the oath. Besides, the inquisitor could grant bail or have reliable bondsmen to stand surety.

Medieval courts used torture as means of eliciting the truth. The inquisition adopted the method a few decades after its inception – and it is still part of judicial inquiry in many countries. However, torture was permitted only after all other expedients (counselling, coaxing, instilling fear of death, and even confinement) had been exhausted, or if the accused was inexact in his statements and virtually convicted by manifold and weighty proofs.

Torture was to be applied only at any one stage of the inquiry and without causing loss of life or limb. Many a judge skipped this procedure, considering it deceptive and ineffectual, but there were others who depended on it and even exceeded their authority. This made the inquisitor and other officials liable for suspension. Sometimes pressure was exerted in this regard by the civil authorities, overshadowing the ecclesiastical purposes of the inquisition.

While it was mandatory to have depositions by at least two witnesses, some judges would demand more. The Church initially believed that testimony of an "infamous" person was worthless before the courts, but later began to accept their evidence at nearly full value in trials concerning the Faith. Similarly, while at first it was a rule to withhold the names of the witnesses from the accused person, by and by naming witnesses was mandatory, but no personal confrontation of witnesses or any cross-examination ever allowed. Needless to say, false witnesses were severely punished.

It is a pity that witnesses hesitated to appear for the defence, fearing that they would be suspected of heresy. Similarly, the defendant rarely secured legal advisers, so those accused were obliged to respond personally to the main points of a charge. If thrown behind bars, they were given pen and paper for the purpose but no books to read or refer to. Years later, the law provided for heretics to be granted a legal adviser who was beyond suspicion – upright, skilled in civil and canon law, and zealous for the faith.

The accused could let the judge know his enemies; and should these turn out to be the accusers in the case, the charges would be quashed.

c) Bishop and the councils: These were introduced as a system of checks and balances, to save the inquisition tribunals from arbitrariness and caprice. The accused were also referred to the bishop who together with the inquisitor and a number of boni viri – upright and experienced men well versed in theology and canon law – would be summoned for the purpose of deciding on two questions: whether guilt lay at hand and what punishment was to be inflicted.

To preclude personal considerations, cases would be submitted to the council without naming any names. The role of the good men was advisory in nature, yet the final ruling was usually in accordance with their views.

The inquisitors were also assisted by a consilium permanens, or standing council, composed of other sworn judges.

d) Revision: When a decision was revised, it was in the direction of clemency.

e) Imprisonment: If the prison conditions were not up to the mark, the local bishop was supposed to look into the matter. If necessary, he would have meals provided to the prisoner from the proceeds of the confiscated property belonging to the latter.

f) Right to Appeal: The accused could reject a judge if he sensed some prejudice and, at any stage of the trial, appeal to a higher tribunal in the country’s capital or in Rome. The documents of the case would be dispatched there under seal. People would not do so as a matter of course, considering the time and money that it entailed; but sometimes it was considered worth the effort.

g) Punishment: One or two days prior to the formal pronouncement of the verdict,the charges were read out to the respective persons again and in the vernacular. Then they would be told where and when to appear to hear the verdict.

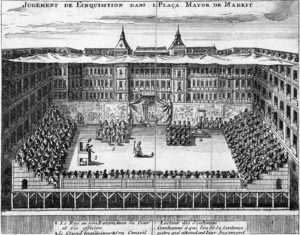

The final decision was usually pronounced with solemn ceremonial at the sermo generalis (a short discourse or exhortation), which later came to be known as auto-da-fé (act of faith). This was not a regular affair; it was held biennially or triennially, or even more rarely.

The auto-da-fé ceremony began very early in the morning. It comprised Mass, prayer, a public procession of those found guilty, and a reading of their sentences. It was followed by the investiture of the secular officials, who were made to vow obedience to the inquisitor in all things pertaining to the suppression of heresy. The so-called "decrees of mercy" (commutations, mitigations, and remission of previously imposed penalties) were followed by a fresh listing of offences and due punishments assigned to the guilty.

The listing went on from the minor to the major punishments, all of them as per the law in force. Some punishments were simply penitential in nature: building or visiting a church, going on pilgrimage more or less distant, offering a candle or a chalice, and the like. Minor punishments also included fines; road-making; whipping; the pillory, and so on. Major punishments comprised imprisonment in various degrees; confiscation of property; excommunication and the consequent surrender of the accused to the civil power for life imprisonment or death at the stake.

The auto-da-fé brought the inquisitional proceedings to an end.

h) Victims

For some, the word ‘Inquisition’ conjures up dreadful images of people arbitrarily sent to the stake. But the facts don’t bear out those fears. What those unscrupulous critics have done down the centuries is point out a few high-profile cases of clerics, scientists, and even saints (St Joan of Arc, Galileo Galilei, Edgardo Mortara, Giordano Bruno, among others) and then generalise about the inquisition. And about these heavy-weights, they hardly ever qualify their remarks.

Punishments in perspective

The indisputable fact is that, due to partial unavailability of records, many finer details are not known for sure. For instance, the number of those who died at the stake cannot be determined even with approximate accuracy. No serious historian, however, has ever stated that the figure is unconscionably high, for available data bears out the contrary. In fact, the numbers seem very low compared with the high-sounding rhetoric surrounding the tribunal.

Beginning from the nineteenth century, historians gradually compiled statistics drawn from the surviving court records. For instance, according to information available on Wikipedia, Inquisition historians Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras studied the records of the Spanish Inquisition, which list 44,674 cases of which 826 resulted in executions in person and 778 in effigy (a straw dummy was burned in place of the person). Professor William Monter estimated there were 1000 executions between the years 1530–1630 and 250 between the years 1630–1730. Spain specialist Jean-Pierre Dedieu studied the records of the Toledo tribunal, which put 12,000 people on trial. For the period prior to 1530, British historian Henry Kamen estimated there were about 2,000 executions in all of Spain's tribunals. Italian Renaissance history professor and Inquisition expert Carlo Ginzburg had his doubts about using statistics to reach a judgment about the period given that in many cases the evidence has been lost.

The same holds true for Goa, where the first tribunal outside Europe was established in the year 1560 and functioned intermittently up to 1812. According to history professor José Pedro Paiva of Coimbra, there are many reasons for the loss of the original archival sources pertaining to Goa. Meanwhile, he reckons that out of approximately 15,000 trials, there were more than 200 death sentences over a period of 250 years.

Further, The Catholic Encyclopaedia too provides valuable statistics about a few Inquisition tribunals in France. At Pamiers, from 1318 to 1324, five out of 24 persons convicted were delivered to the civil power; and at Toulouse from 1308 to 1323, only 42 out of 930 similarly bear the ominous note relictus culiae saeculari. At Pamiers one in 13 and at Toulouse one in 42 seem to have been burnt for heresy, even while these places were hotbeds of heresy and principal centres of the Inquisition, and the period the most active one for the institution.

Even when confronted with such unimpressive numbers, those biased critics make it a point to dub punishments of a bygone era ‘atrocious, ‘barbaric’, ‘cruel’, and so on. They conveniently forget that the same could be said of modern societies that blatantly, whimsically, and sometimes furtively engage in such acts, so unbecoming of purportedly enlightened democracies.

It would therefore be apt to conclude this section by quoting Robert Held, an anti-torture and anti-death-penalty proponent, who puts torture in perspective in his book titled Torture Instruments: “Neither the Roman nor the Spanish Inquisition used methods in any way different from those in everyday use by secular justice everywhere – in this sense it is an error to think of stake, rack and wheel as inventions of or even as attributes peculiar to either. Nothing went on in inquisitional dungeons or places of execution that would have seemed excessive, let alone unusual, to any plebe, prince or burgher of the times.”

The same could be said of the Goa Inquisition – but it is not our intention to elaborate on the subject at the moment. In the forthcoming and final instalment of this three-part series we shall proceed to draw up a general assessment of the redoubtable tribunal in question.

(To be concluded...3)

What was the Inquisition? – 1

The Inquisition has long been made to look monstrous. The Essential Catholic Survival Guide reckons that “to non-Catholics it is a scandal; to Catholics, an embarrassment; to both, a confusion.” Indeed, our generation shies away from its memory or, if caught on the back foot, quickly turns apologetic. It is as though we are under a spell, and this is the handiwork of those inimical to the Catholic Church or at least unaware of the real functioning of the court that was the Inquisition.

The point here is not to whitewash a much maligned institution but to understand its nature. We are before a formal tribunal, not a mere people’s court; that this court had well established procedures, similar to modern courts in many ways and, obviously, following contemporaneous standards of justice, however alien they may seem to our generation. And given the lack of documentation, it is unreasonable to depend on statistics alone to make up our minds about that institution.

Definitions

‘Inquisition’ and ‘Heresy’ are two terms that call for special attention. The first one, from the Latin inquirere, meaning “to inquire”, refers to questioning. Roman law provided for an inquisitorial procedure by magistrates investigating crimes in the absence of formal charges being brought to their attention. After the Empire converted to Christianity in the fourth century, the procedure was employed by emperors from Constantine onwards to investigate heresy and related cases. It behoved the State to uproot this crime which always had socio-political implications; it was only in the second millennium that the Pope intervened, to rein in excesses, by setting up a formal tribunal, though not fully successfully.

Heresy isn’t the same thing as incredulity, schism, apostasy or some such sin against the faith. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines heresy as “the obstinate post-baptismal denial of some truth that must be believed with divine and Catholic faith; or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same.” The doubt or denial involved in heresy concerns a matter that has been revealed by God and solemnly defined by the Church, be it the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, Papal Infallibility, the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary.

It was the task of the Inquisition to ascertain whether a person was guilty of propagating a heresy. Mere holding of wrong notions of Catholic doctrine privately did not attract sanctions from the court. Only a person found to be spreading those views came under the scanner of the Inquisition; and only refusing to be corrected would be considered heretics.

The Inquisition judged Christians; it was thus no torture plan to convert people to Christianity, as it is made out to be. Neither was it an instrument of evangelisation nor were there ever any provisions under Church law for the use of force to convert a person to the faith. The Inquisition aimed primarily to try and reform the accused and win them back to the faith. However, as heresy was an offence under the law, the tribunal, like a parent punishing an intractable child, would have hardened offenders penalised, so as to safeguard the common good. In those days, when Church and State were united, like soul and body, the law holistically catered to the citizens’ spiritual and material welfare. It goes without saying that very often the State overruled the Church, disparaging the spiritual and reformatory aspect and exalting the material and punitive side.

Historical development

Like Moses who was anguished by his people’s worship of the Golden Calf, the Christian Apostles too were deeply concerned about guarding and transmitting the deposit of the Faith undefiled. Unfortunately, not only the early days of Christianity, the whole of the first millennium was riddled with heretical doctrines: the Circumcision heresy (1st c.); Gnosticism (1st-2nd cs.); Montanism (late 2nd c.); Sabellianism (early 3rd c.); Arianism (4th c.); Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism (5th c.); Nestorianism (5th c.); Monophysitism (5th c.); Iconoclasm (7th-8th cs.) and Catharism (11th c.). The Church authorities suffered the consequences of those heresies but, rather than opting for the Old Covenant penalties of death or scourging, simply excommunicated the heretic.

On the other hand, the imperial successors of Constantine, who regarded themselves as masters of the temporal and material conditions of the Church, were persuaded that it was their first concern to protect the State religion. Heresies generated anarchy, so penal edicts (confiscation of property and death) were issued regularly against heretics. A law of the year 407 asserts for the first time that heresies ought to be equated with high treason. For their part, the church authorities in the Christianised states of the Roman Empire refused to invoke the civil power against the heretics.

Ironically, it was the heretics who appealed to the civil power for protection against the Church, and before long complained bitterly of administrative cruelty. At this point, Bishop St Optatus of Mileve defended the civil authority, thus championing for the first time a decisive cooperation of the State in religious questions and its right to inflict death on heretics. This matter wasn’t settled unequivocally given that several ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel. St Augustine was one such bishop who tried to lead back the erring by means of instruction. However, he changed his views, perhaps moved by the incredible excesses perpetrated by the heretics. Yet, it was the desire of the bishop of Hippo to correct them, not put them to death; he wanted the triumph of ecclesiastical discipline, not the death penalties that they deserved.

Meanwhile, as often as the social welfare required it, Christian rulers sought to stem the evil with appropriate measures. In an attempt to save the kingdom and save souls, even distinguished citizens, ecclesiastical and lay, were burnt at the stake. Often there were outbursts of Christian popular sentiment against dangerous sectaries. Sometimes the people blamed the clerical softness in pursuing heretics and so took the law into their hands. Kings and bishops responded by condemning heretics to the stake to prevent the spread of what they called “the heretical leprosy”.

According to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, a definitive strategy came about after Frederick Barbarossa, the powerful king of Germany and Sicily, and Pope Alexander III reached an accord reconciling their respective powers in the Peace of Venice in 1177. This was reaffirmed at the Lateran Council of 1179. In 1184, Pope Lucius III issued the decretal Ad abolendam (‘To abolish diverse malignant heresies’) which some have called the “founding charter of the Inquisition”. It commanded bishops to take an active role in identifying and prosecuting heresy in their jurisdictions. Heretics would suffer excommunication from the Church and be handed over to the civil power to be punished according to the provisions of the common law.

Accordingly, the first Inquisition tribunal was established in southern France in 1184. While death was still not on the cards, punishment was limited to exile, expropriation, destruction of the culprits dwelling, infamy, debarment from public office, and the like. The explicit identification of heresy with treason and its prosecution according to the norms of Roman law was formalised in 1199 by Pope Innocent III. At the Lateran Council of 1215, a relative service was done to the heretics by the introduction of regular canonical procedure to abrogate the arbitrariness, passion and injustice of the civil courts and from the penal codes in Spain, France and Germany.

New Challenges

Although medieval Europe was a society of Catholic kingdoms, adherents of other religions, particularly Judaism and Islam, also lived there. In the first few decades of the thirteenth century, Christian Europe was so endangered by heresy that a formal ecclesiastical tribunal under direct papal jurisdiction became a social, religious and political necessity. Pope Gregory IX established the so-called Monastic Inquisition by his Bulls of 13, 20, and 22 April 1233, appointing Dominican monks as the official inquisitors for all dioceses of France. The Inquisition had jurisdiction only over the Catholic populace; non-Catholics would be hauled up only if found to be perverting Catholic mores. At a time when the people had higher regard for the soul than for the body, heresies were spiritual terrorism to be tackled with vehemence, just as we do against acts of physical violence today.

Broadly speaking, the new tribunals of the Inquisition established in Europe and Asia faced many challenges, some of which are listed below:

a) Catharism (13th century)

These sects were a social menace right from the Byzantine period. They were treated with severity, yet they poured over all of Western Europe. A mix of religions reworked with Christian terminology, Catharism was an umbrella for multiple sects, one of the largest being the Albigensians. By and large, they were not only hostile to the Mass, the sacraments, the ecclesiastical hierarchy and organization, and to the government; their views were fatal to the continuance of human society as they forbade marriage and made a duty of suicide. It was only natural that both Christian and non-Christian custodians of the existing order in Europe should adopt repressive measures against their aberrant teachings.

b) Conversos (15th century)

Pope Sixtus IV empowered Ferdinand and Isabella to set up the Inquisition in Spain in the year 1478, to confront the conversos, pseudo-converts from Judaism (Marranos) and from Islam (Mouriscos). The tribunal turned very fierce even by the standards of the time, so much so that the Pope made efforts to limit the powers of the inquisitors but to hardly any avail. In 1483, a Grand Inquisitor and Supreme Council was appointed to supervise local inquisitorial tribunals, including the later ones in Mexico and Peru. The first Grand Inquisitor, the Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, also exceeded his powers.

c) Protestantism (16th century)

At the turn of the sixteenth century, Europe found itself divided into two ideological blocs: one Catholic and obedient to the Pope; the other, Protestant and opposed to the Pope. After Luther, Calvin and Henry VIII parted ways with the Catholic Church, each began spreading theological ideas that were in conflict with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Their movements began to gain ground in various principalities and kingdoms of northern Europe.

The great apostasy or disaffiliation from the Catholic Church prompted Pope Paul III to establish the Sacra Congregatio Romanae et Universalis Inquisitionis seu Sancti Officii (Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, or the Holy Office), in 1542. It consisted of a commission of six cardinals. They were at once the final court of appeal for trials concerning the Faith and the court of first instance for cases reserved to the Pope. It inaugurated an era of institutionalised inquisitions. Succeeding popes made further provisions for the procedure and competency of the Inquisition of which Pope Sixtus V is regarded as the reorganizer.

In that same year, the Pope made known the first list of books prohibited for their doctrinal content or criticism of the Catholic Church. A more comprehensive Index of Prohibited Authors and Books was brought out after the Council of Trent (1545-63). Later, a separate though related Congregation of the Index updated the list.

d) Paganism (16th century onwards)

This is an umbrella term for beliefs held by polytheistic religions. It applied especially to the religious beliefs of the natives of the colonies held by Portugal and Spain in Asia, Africa and Latin America. King João III of Portugal applied to the Pope for an independent Portuguese Inquisition to deal specifically with threats posed by crypto-Jews in his country. A branch of the tribunal was set up in the city of Goa in 1560 to handle cases relating to the ethnic Portuguese in India and to neo-converts to Catholicism (Jews, Hindus and Muslims) relapsing into their former religions or practising them side by side with Catholicism.

e) Heterodoxy (18th century onwards)

This refers to views that differ from right belief or purity of the Faith, or say, orthodox views. ‘Right belief’ is not subjective, as resting on personal knowledge and convictions, but that which is in accordance with the teaching and direction of an absolute extrinsic authority.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Eventually, Rationalism, or the use of human reason or understanding as the sole source and final test of all truth, began to form the basis of intellectual and scientific activity. It seemed to hold out a promise of dramatic improvement in human life. These tendencies finally led towards religious disbelief, evident in such modes of thought as atheism, agnosticism, materialism, naturalism, pantheism, scepticism, and the like.

New Winds

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the stage was set for republican revolts against European monarchies, beginning in Sicily and spreading to France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire. They ended in failure, repression and widespread disillusionment among liberals.

Nonetheless, winds of liberalism kept blowing hard, unsettling the traditional ways of thinking. Reason continued to score points against faith and displace it across Europe. In fact, religious beliefs began to be equated with blind faith; so faith looked weird when juxtaposed with free private judgement. The view that orthodoxy should be maintained at all cost began to be looked upon with suspicion.

With religion itself relegated to the background, how could a mere institution that stood staunchly for preserving the deposit of the Faith be welcome? Here was a propitious moment for dissenters to quickly and impudently go about their business of discrediting the Catholic Church. The process that had started with the Protestant Revolution gained steam with the French Revolution. It is no wonder, then, that we moderns experience difficulty in grasping the rationale of the Inquisition. The punishments meted out by the tribunal for heresy seem exaggerated, not to say irrational and misplaced.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

How are we to explain the Inquisition in the light of its own period? To do justice to the topic, we need to first have a look at the broad features of the tribunal of the Inquisition.

(To be continued… Part 2)

Three Cheers to Abade Faria!

Three episodes among many others in the life of Abade Faria call for resounding cheers. The first is that he grew up under very unusual and trying circumstances, yet came out a champion. Born Joseph Custódio de Faria, in the year 1756, his parents Caetano Vitorino de Faria, who hailed from Colvale, and Rosa Maria de Souza, from Candolim, separated canonically within ten years of marriage. Thereafter, the husband took holy orders in the then seminary of Chorão; the wife joined St Monica, Asia’s largest nunnery, as a lay sister of the white veil. And the three were never together again as a family.

In such a situation, José Custódio came across as an oddity. He must have had a lot of explaining to do wherever he went. In those days, how was it to be raised by a single parent? This aspect of Goa’s forgotten celebrity hasn’t received attention from historians and psychologists. At fifteen, José Custódio travelled with his dad to Lisbon, en route to Rome. Priestly studies awaited him at the Pontifical Urban University. And both father and son secured doctorates in the Eternal City. The young man left no stone unturned in his solitary yet creative life.

The second reason to celebrate Abade Faria is that he sailed uncharted seas. He spent eight years (1780-88) with his nativist father, who was considered the ‘patriarch and patron’ of the Goan community in Lisbon. Then, Faria Jr. went to France, in search of greener pastures. His arrival coincided with the political turmoil of the Revolution, when royalists and clergy alike were getting a raw deal. He bided his time until 1795 when he placed himself at the head of a revolutionary battalion and marched against the National Convention. The five-member Directory that seized power ended the Reign of Terror; they also relaxed the measures that had been instituted against exiled priests and monarchists. Fr. José Custódio de Faria thus had the curious distinction of being the one and only Goan participant in the French Revolution.

By now, the Goan cleric was ‘Abbé Faria’ to everyone. ‘Abbé’ is French for priest or abbot; in Portuguese they wrongly called him ‘Abade’ (abbot), which he was not! As though compensating for that mistranslation, the father’s clarion call in Konkani was properly captured by bystanders: “Hi soglli bhaji… Kator re bhaji!” – ‘Strawheads all, chop them off!’ And that’s how a concerned father rescued his preacher son awestruck in the pulpit, before the Queen and the nobility gathered in the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

There is no hard evidence to support that claim but the senior Faria’s alleged cry has long been part of the Goan lore. I have a hunch that this set the ball rolling for an unprecedented career for the junior Faria. That legendary transformation brought about by half a dozen, suggestive words uttered by a devoted father must have rung in the son’s ears for a long time to come. It may be facile to connect the episode to the theory of hypnotism by suggestion that Abade Faria pioneered, but here it goes nonetheless!

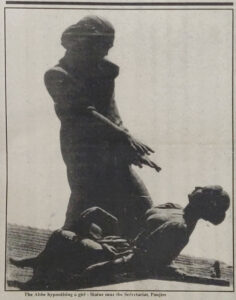

After a stint as professor of philosophy in the port city of Marseilles in 1811, the Abbé finally settled down in Paris where he gave sessions of hypnotism. He died there in 1819, but not before rejecting Mesmer’s animal magnetism and expounding a new theory of hypnotism. Faria put the subject on a sound footing, coining the term sommeil lucide (lucid sleep). He dwelt on this at length in his magnum opus, titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou étude de la nature de l’homme, that is, ‘Of the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study of the Nature of Man’, which was published posthumously. And it is a pity that the remaining three volumes never saw the light of day.

Abade Faria made a seminal contribution to the field of science. Hypnosis soon became a vital aid to physiology and medicine, and is still so to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. No doubt, the discoverer was initially derided by doctors, writers, and pastors, but the scientist came out victorious. Today, he is universally regarded as the ‘father of modern hypnotism’.

Three cheers, then, to the greatest untrained Goan scientist of all times, on his 200th death anniversary today!

(The Goan, 20 September 2019)

http://epaper.thegoan.net/2335415/The-Goan-Everyday/The-Goan-Everyday#page/10/1

The Hypnotist in Holy Orders

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

He is better known as a personage in Alexandre Dumas’ novel The Count of Monte-Cristo Chateaubriand mentions him, albeit in derogatory terms, in his memoirs. In Goa, he is only vaguely known for his father’s cry ‘Hi soglli bhaji!’ which instantly filled with confidence the faltering preacher son at the royal chapel at Queluz, Portugal.

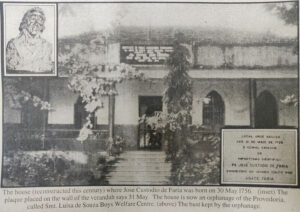

Precious little remains till date in the memory of the average Goan. There is a statue of him in the capital city and a street takes his name in Margão. He has been forgotten in his native village of Candolim; only a primary school is named after him there and in some other villages too. He is almost unknown where he worked and lived – Lisbon, Paris and Marseilles. Only an obscure street is named after him in Marseilles.

People may not be apt to remember somebody who lived two centuries ago and with a mysterious sounding name such as Abbé Faria. But what if he has some original scientific contribution to his credit? Never mind that he was a theorist of hypnotism by suggestion, which has since become a vital aid to psychiatry, psychoanalysis and surgery. Very often his name is omitted when the subject comes to the fore. Not even does the Encyclopaedia Britannica refer to him as they do Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815) and James Braid (1795-1860), who have only usurped his pride of place.

Such has been the fate of José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819), a priest and doctor of theology, who without any medical training did perceive and lend respectability to the true nature of what he called ‘sommeil lucide’ (lucid sleep). It was an intuition characteristic of a true genius. And for this original contribution to the field of science he is regarded at home as the greatest Goan that ever lived.

Early Life

José Custódio de Faria was born on 31 May 1756, to Caetano Vitorino de Faria of Colvale and Rosa Maria de Souza of Candolim. His father was a seminarian and had already received minor orders when he met and married Rosa, the only daughter of a rich landlord of Candolim. He was clever and she was rich, but the combination did not work out that well. Even their son born two years after their marriage, could not prolong their mutual love. Around the year 1764, they got a canonical decree of separation in 1764. He took holy orders and she joined the Santa Monica convent in the  old city of Goa.

old city of Goa.

No bonds linked them ever since. The father and the son stayed a few years at their friends in Candolim – the Pintos of the Conspiracy fame – and at Colvale too. On 21 February 1771, four years after being ordained a priest, Caetano Vitorino left for Lisbon, en route for Rome, to continue his priestly studies. He had similar intentions for his son. Their social circle in Goa and particularly a letter of recommendation they carried for the nuncio in Lisbon, Mgr. Inocencio Conti, won them access to the royal court. Moreover, the reigning monarch, Dom José I, and his prime minister, the Marquis of Pombal, were favourably disposed towards the Goans, whom they strongly recommended for civil, military and ecclesiastical positions at home.

Student in Rome

Thus José Custódio was awarded a scholarship to study in Rome. The father returned to Lisbon in 1777 on attaining a doctorate to further his objective of objective of being appointed the bishop of Goa. His great disappointment and frustration on this count determined much of what followed in his life and his son’s too.

José Custódio stayed on and was ordained on 12 March 1780. At 24 he completed his doctoral thesis titled Theologicae Propositiones: De Existentia Dei, Deo Uno et Divina Revelatione (Theological Propositions on the Existence of God, One God and Divine Revelation) and joined his father in Lisbon.

The duo were good friends but a different purpose animated them. Caetano Vitorino, the more political minded and diplomatic of the two, was fully immersed in matters Goan. He was a sort of self-appointed protector of and influential reference for the Goan community. The Court had been impressed by the fact that, though immensely influential at the highest levels of the kingdom’s administration, he had never asked favours for himself, though it was known that his personal finances were far from bright. But then, intelligence reports began to pin him down as the mastermind and coordinator in Lisbon of a political revolt at home in 1787. As soon as news of this reached Lisbon, they hunted for the duo and their good friends, clerics and laymen.

Meanwhile, all except Fr. Caetano Vitorino had fled to Paris, reportedly to meet and discuss with their envoys of Tipu Sultan, who proposed to be on the French side in their ascendancy against the British in India, but nothing was confirmed in this respect. Others believe that simpler reasons motivated Fr. José Custódio’s sudden departure – that he was attracted by the intellectual climate of France. His father did, however, stay back, still persevering in his designs and probably even overestimating his influence with the high officialdom. He was then put under house arrest in the Carmelite convent where he gave his priestly assistance, and probably died in 1799.

In Paris

Nothing is known of Fr. José Custódio’s activities in the French capital except that he was accused, in 1792, of being a gambler and frequenter of the Palais-Royale. He was acquitted, or at least no action was taken against him by the police. Three years later, on 5 October 1795, he led a battalion of revolutionaries against the National Convention. This political stand made him popular with the supporters of the Directoire and won him the friendship of the Marquis de Chastenet de Puységur.

The latter relationship was decisive. The Marquis had been a disciple of Mesmer whose quackish furrows into ‘animal magnetism’ and tall claims of cures had initially won him the acclaim of high Parisian society. But, in 1785, his exit was shameful. The Marquis, on the other hand, was an honest, well-meaning and cultured person, who took over from where Mesmer had left. Dr Egas Moniz, the Portuguese Nobel Prize Winner and biographer of Fr. José Custódio de Faria, speculates that he acquired knowledge of magnetism in Paris after he struck up an acquaintance with the Marquis.

The first news of Fr. Faria’s activity as a magnetizer is of the year 1802, in the memoirs of Chateaubriand (published in 1843), who referred to his experiments in derogatory terms. He had dined with Fr. Faria at the house of the Marchionesse of Custine. Here, Fr. Faria reportedly declared that he could kill a canary by magnetizing it. However, when the magnetizer was put to the test, he failed, which led Chateaubriand to conclude: ‘O Christian, my presence itself will be enough to make the tripod ineffective!’ Chateaubriand was a devout Catholic. He had strong reservations against magnetism – because of the Church’s attitude of suspicion towards it. But what is more is that Fr. José Custódio de Faria was a Catholic, no less!

Fr. José Custódio continued his research into the subject up to the year 1811, when he was appointed professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Marseilles. The Imperial Almanac of 1811 records that he lived there a year and was elected member of a medical society. Since he had no medical qualifications, the membership can only be attributed to his skills as a magnetizer. But for some mysterious reason, he was transferred, in fact, demoted, to the post of auxiliary professor at the Academy of Nimes. He felt slighted and frustrated and, unaccustomed as he was to life in a small city like Nimes, he returned to Paris, in 1813, in search of greener pastures. Unattached to any institution, he initiated his course in magnetism on 11 August 1813, 49, Rue de Clichy.

Sessions

The sessions were held every Thursday, on an admission fee of five francs only. He began with a lecture in halting French. The audience, which consisted largely of women, paid scant attention to this part of the session; their eyes were set on what was to follow – his experiments to substantiate his theory.

Contrary to the claims made by Mesmer, the he could control the body fluids of his patients and rectify their course through special methods invented by him, Fr. José Custódio very humbly put forth that not all individuals could be hypnotised, and that the degree of response to his hypnotic powers necessarily varied from person to person. He was the first to establish that hypnotism was a science of suggestion.

Fr. Faria’s method consisted of a series of well-reasoned and effective actions: he got the patient to sit comfortably and, through concentration, to relax, imagining that they were going to sleep. When the patient was ‘tranquil’, he gave the command, ‘Sleep!’ and, if necessary, repeated it, with a certain degree of urgency, three or four times. If he failed, he would either sportingly give up or try other methods.

The sessions became the rage of the town. There were detractors, critics and skeptics, no doubt. Once, a journalist attended his session and then unjustly criticised and ridiculed the priest in the press. At another session, a leading stage actor, Potier, offered himself for his experiments. He feigned to be in a trance and suddenly rose to say, ‘Ah, Abbé! If you magnetize others as well as you magnetized me, you don’t seem to be doing much.’

Fr. José Custódio put up very well with all such betrayals. He also withstood quite stoically criticism from the clergy and Rome, who then viewed his experiments with suspicion always on the look-out for diabolical influences therein. But the priest always expressed respect for the Church and a firm desire to stay within the Catholic fold. ‘Un esprit supérieur,’ as his disciple Gen. Noizet said of him, he wished to convince the Church that his experiments were fully within the natural realm and that there was no magic or witchcraft involved.

Thus, Fr. Faria took everything in its stride. Only once did he break down, when at Potier’s request the playwright Jules Verne put up a play, on 5 September 1816, the Variétés, titled La Magnétismomanie, ridiculing the Goan priest.

Sad end

The time was now ripe for Fr. Faria to stop his activities. He retired soon thereafter, rendering priestly services in exchange for boarding and lodging.

During the last years of his life, he decided to organize his material in book form. It was an ambitious project in four volumes, of which only the first one is known to have appeared. It is his magnum opus is titled De la cause du sommeil lucide ou Étude de la nature de l’homme (On the Cause of Lucid Sleep or Study on the Nature of Man). In it he referred to the shameful play:

‘With regard to Magnétismomanie, I cannot ask which laws permit the modern Terence to expose an unknown foreigner to public ridicule. I presume that even the savage would be ashamed to insult his kind, which has nothing in common with actors and the theatre.

‘Far from me the idea to disturb public pleasures: But I might have added to Magnétismomanie a new scene – an extremely pungent one – had my condition not prevented me from doing so, and had my own aversion for such amusements not kept me away from playhouses.’

According to one biographer, by a strange coincidence, the day of his death, also marks the release of his book. His famous words, ‘There are evils that sometimes do good to those who discern their utility,’ might have very well served as his epitaph – if only he had the money for a decent burial. He died at the age of 63, unsung as he was born. A life full of ironies, for born of a rich family he died poor; born of parents who were in love, they separated after his birth; a man with original contributions to posterity, he died with no godfathers to promote his name.

(Herald Illustrated Review, Panjim, Goa. Vol. 95, No. 30, February 1-15 1995. Slightly updated version)