THE PORTUGUESE PRESENCE IN INDIA, by João A. de Menezes. Chennai: Notion Press, 2020. Pp 346. ISBN HB 978-1-64850-628-4. Rs 1610/-

This is not macro-history like Danvers’ or Whiteway’s, but an account of the author’s life spent in the bosom of a third culture moulded by the Portuguese presence. In five autobiographical chapters interspersed with four others on broader historical issues he speaks his mind with a forthrightness not common in our days.

Three main strands stand out: the Goan way of life (“Goanism”), including emigration; the Catholic Church in Portuguese and British India; and Goa’s démarches in post-Independent India. “Goanism”, says the author, is anchored to the 451-year-old Portuguese stint and to the age-old comunidades that since the Vedic times have engendered powerful village loyalties.

The author’s own “loyalties” are evident. Despite the author’s long years in Poona, Aden, Bombay, and travels abroad, his heart beats for Goa. There are tender descriptions of ancient institutions; villages and households; the local church and cross feasts; markets and transport systems. Menezes is proud of icons like the Patriarca das Índias Orientais, the Cathedral See, the capital city Pangim, Radio Goa of yesteryear, the Taleigão harvest festival; and he gratefully remembers Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes, other men (priest granduncles Canon Bruno de Menezes and Fr Hipólito de Luna included), and matters that contributed towards shaping Goa (“with the exception of the Governor-General and the Chefe do Gabinete, all the other officials of the civil services were Goans and men of integrity”, p. 45).

“Visit to Goa… for the 1952 Exposition” (of the Relics of St Francis Xavier) portrays Menezes as a young man, not only curious about the history of the former capital of the Portuguese Eastern Empire but also attentive to the political goings-on: the “problematic emergence” of the first Indian Cardinal, Valerian Gracias (and his sojourn at Panjim’s Hotel Imperial); pressures on Portuguese India; redistribution of Padroado territory in British India, and so on.

That visit hooked Menezes to his homeland. In “A Tryst with Goa”, he appreciates the cordiality from family and friends, set in a social ambience in which house doors “could remain open with no fear of intrusion” (p. 246). But “the happiest place on earth” (p. 274) was not destined to remain the same for long. The first satyagraha, which involved 100 (out of 100,000) Bombay Goans, in 1954, and none in the following year, demanding ‘liberation’ at the Goa border (p. 264); the severance of diplomatic ties between the Indian Union and Portugal; the Economic Blockade and terrorist threats, which made travel by land a nightmare, and the like, seem to account for the book’s subtitle, “Latter-day thorns amidst tranquillities”. Menezes participated in a first-of-its-kind pilgrimage to Old Goa, praying for peace, in 1956.

Menezes records Goa’s coming of age amidst those “thorns”, thanks to the induction of Transportes Aéreos da Índia Portuguesa (TAIP, whose airhostesses wore saris); upgradation of travel by land, sea, rail and air; optimising of farmland and other resources; importation of cars (Opel and Mercedes Benz as taxis, and the concept of shared taxis, p. 248) and other products; and boost to mining, with Chowgule & Co. as a concessionaire operating an iron loading facility while the rest of the port was managed by the British company that ran West of India Guaranteed Portuguese Railway (WIPR; p. 259).

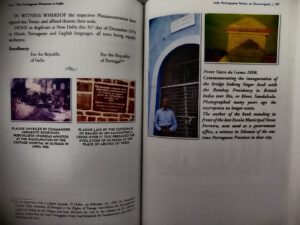

In two chapters – “My Return to India from Goa” and “Travel between India and Portuguese India” – Menezes dwells on the run-up to the events of December 1961, viz. strategies to dismantle the Portuguese presence; the Goa Office at the Bombay Secretariat, among others. While the Brazilian Embassy’s service to Goans applying for Portuguese passports comes in for special praise here, the subject is dealt with extensively in “Brazil, Caretaker of Portugal’s Interests in the Indian Union – September 1, 1955 to December 31, 1974”. On the latter date, Portugal opened its Embassy in New Delhi.

Three chapters on lesser-known subjects – “The Portuguese Padroado or Patronage and the Indian State”; Indo-Portuguese Notes on Sovereignty”; and “The Referendum Rub: The Inflexibility of the Indian State to permit a Referendum” are mini-dissertations indeed. Menezes draws up a concise history of the Padroado (respected by the Peshwas) and of the Holy See-Portugal Concordat of 1940 (with text in English), and the implications for Goa. His unique contribution lies in examining the impact of Indian Independence on the Padroado, for which purpose he painstakingly translated and critiqued the India-Portugal correspondence contained in the four-volume White Paper titled Vinte Anos de Defesa do Estado Português da Índia (1947-1967), an invaluable resource for researchers.

To put together “Indo-Portuguese Notes on Sovereignty”, Menezes falls back on those diplomatic exchanges, declassified ahead of time (“an act without international precedent”) so the ageing Salazar could let the world know that he had defended the Portuguese Settlements in India with integrity (p. 131). Menezes calls the bluff of Goan political parties’ contribution to the fall of Dadrá and Nagar-Aveli (p. 171 ff) and ends the chapter with a note on “the conquest and subjugation of the Portuguese territories in India” (pp 182-3), with the text of the Indo-Portuguese Treaty of 31 December 1974 (p. 183 ff) added. The Appendix comprises a Goan, Bonifácio de Miranda’s address (apropos the Goa Case) at the UN General Assembly in 1969.

Finally, “The Referendum Rub” is the book’s pièce de resistance. Highlighting UN Charter’s principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, Menezes points to Chandernagore as the subcontinent’s only foreign settlement territory where a referendum was held to determine its political future. Although a referendum for Goa had votaries, “no such referendum was admissible or mandatory under the Estado Novo Constitution of Portugal” (p. 214). In Menezes’ opinion, even if it were permitted in Goa, “weighing the nuances, a referendum might have created more problems than it could solve” (p. 215). In hindsight, “Professor Aloysius Soares’ proposal of Portuguese autonomy [according] to a special constitution followed by a transfer to India with that constitution in place was a pragmatic approach to the future of the Portuguese territories…” (p. 219)

The Portuguese Presence in India, by João A. de Menezes, 90, who retired as chief mechanical engineer of Bombay Port Trust, is truly a labour of love, never mind the publisher’s price tag. A storehouse of memories and musings, blessed with period photographs and good get-up, the hardcover book printed on art paper could have done with better editing, bibliography and index. It is nonetheless a precious contribution to contemporary Indo-Portuguese history and a testament to the author’s love for Goa and insights into her soul.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 25, Nov-Dec 2023, pp 44-46)