It is interesting to note the Liturgy of the Word on Palm Sunday, also referred to as Passion Sunday. While the first two readings and the psalm – Is 50: 4-7; Ps 21: 8-9, 17, 18a, 19-20, 23-24; Phil 2: 6-11 – remain the same for cycles A, B and C, the Gospel changes from year to year, highlighting the three Synoptics: St Matthew (26: 14-27, 66), St Mark (14: 1-15, 47), and St Luke (22: 14-23, 56), respectively. They give an account of the Last Supper, the Agony in the Garden, the unfair Trial, the Way to Calvary, and the Crucifixion and Death.

Thus, St John is the only evangelist who does not figure on Palm Sunday. The Beloved Disciple – who offers a selective and somewhat different perspective on the Divine Master, more theological and mystical – is very especially reserved for Maundy Thursday (Jn 13: 1-15) and Good Friday (Jn 18: 1-19, 42), besides two weekday readings. While the Gospel of Thursday focusses on the Last Supper, that of Friday is a Passion narrative that begins with Gethsemane and ends with our Lord’s Death on the Cross.

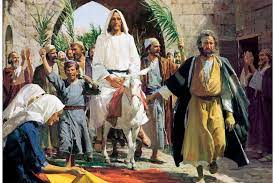

That much for the readings. Now, as regards the designation of the sixth Sunday of Lent: it is officially called ‘Palm Sunday’, recalling the day when Jesus arrived to a hero’s welcome for the Passover in Jerusalem. No wonder, Chesterton’s ‘Donkey’ was ecstatic: ‘There was a shout about my ears, And palms before my feet,’ he said. But what determined the choice of that beast ‘with a monstrous head and sickening cry’, ‘the tattered outlaw of the earth’?

Jesus had walked up to Jerusalem in the past. Although the Synoptics speak of just one Passover, St John states that He celebrated three Passover Feasts in the city of David. Yet, this time he chose to use a donkey, to enter in peace, as a king traditionally did, into a city that was his very own – unlike a conquering king that arrived on a warhorse. Jesus borrowed a colt, which was soon thereafter returned to its owner, fulfilling many Old Testament allusions, the most important being ‘Behold, O Jerusalem of Zion, the King comes onto you meek and lowly riding upon a donkey.’ (Zech 9: 9)

But what were the crowds so excited about that they should thus cheer Jesus? Pope Benedict XVI, in his book Jesus of Nazareth, states that ‘Jesus had set out with the Twelve, but they were gradually joined by an ever-increasing crowd of pilgrims.’ On the way, the blind Bartimaeus who was cured clinched it; he became a fellow pilgrim on the way to Jerusalem. The miracle filled the people with hope that Jesus might indeed be the new David for whom they were waiting.

Jesus was not going to re-establish the Davidic kingdom – far from it! He had always said that his kingdom is not of this world. Yet, the disciples’ act of enthusiastically seating Jesus on that beast of burden was ‘a gesture of enthronement in the tradition of the Davidic kingship’; the pilgrims who, infected by that enthusiasm, joined in spreading out their garments and waving out palms, mirrored a tradition of Israelite kingship; and their exultant cries, though reported differently by the Evangelists, all point to the Old Testament. Still, those players were blissfully unaware that they had fulfilled the Scripture.

The most important part of Scripture, however, was played out by Jesus Himself. He who had come to celebrate the ‘Passover of the Jews’, as the Synoptic Evangelists call it, was in truth observing ‘the Passover of His death and Resurrection’, as St John the Evangelist puts it, for this is what the Saviour said to His disciples: ‘I have been very eager to eat this Passover meal with you before my suffering begins. For I tell you now that I won’t eat this meal again until its meaning is fulfilled in the Kingdom of God.’ (Lk 22:15-16). Jesus fulfilled the Passover by becoming the Sacrificial Lamb.

Our Saviour’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem quickly led to His sorrowful Passion on Calvary. And that is how ‘Palm Sunday’ becomes synonymous with ‘Passion Sunday’ in the Liturgy of the Word.

How aptly you explain the significance of Palm Sunday! It impels me to prayer and reflection.

Thank you, Maria Ana. I find Lent a sort of balm for the soul. How I wish more and more people took advantage of the Lenten period to streamline their life.