The Pope is, by God’s design, a man for his times. As regards Karol Józef Wojtyla, after the initial public scepticism, it became clear that his every facet was a response to the world order of the last quarter of the twentieth century.

We can say without risk of mythologizing that KJW’s personal history matched up with the convulsive era in which he lived. Thanks to his profound faith and compassion, he identified the early loss of his close family[1] with his country’s troubled history. His sense of humour and sportsmanship helped him transform his hard labour under the Nazi regime into empathy for the human condition. His training for the priesthood in the underground seminary of Krakow endowed him with nerves of steel to eventually outwit a repressive political regime. His doctorate on St John of the Cross smoothed out his natural propensity for the ‘via negativa’; his second, on Scheler’s phenomenology, was an exploration into enhancing Christian ethics. By his longtime interest in theatre, he looked at the world as a stage, and later, his university teaching and successive appointments as bishop, archbishop and cardinal[2] gave him a vantage point on global affairs.

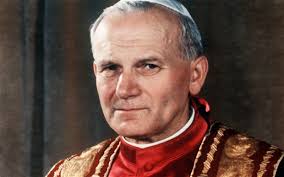

Probably it never occurred to KJW that one day he would be a key player on the world stage. His rise as ‘John Paul II’ in 1978 was indeed sensational: The first ever Pope of Slavic extraction and a non-Italian in 455 years brought palpable hope to far-flung Christendom while his unusually young age was a promise of long innings.[3] His intellectual baggage and experiential knowledge was set to make of his pontificate an ideological and political turning point, marked by healthy opposition, essential restoration and measured innovation.

His main opposition was to atheistic communism. As a passionate Marian (more intensely so after his miraculous escape from assassination attempts)[4] he simply pitted Mary against the Monster, becoming at once a challenge to the Soviet leadership and a beacon of hope to Eastern Europe. He endorsed the simmering anti-communist revolution; it was an initiative that won worldwide support, and amazingly, even from Russia. In Gorbachev’s words, “Everything that happened in these years in Eastern Europe would have been impossible without the presence of this Pope.”

These successes won Pope John Paul II great acclaim as a world statesman but he was essentially the bishop of Rome and the ‘universal pastor of the Church’, a new title that he assumed at the inauguration of his ministry. While he wielded politics and diplomacy with élan he remained at heart a man of intense prayer; he was the mystic behind the Iron Curtain, ensuring that the ‘dark night of the soul’ would steadily make way for the ‘ascent of Mount Carmel’. After dismantling totalitarianism in the East he denounced the liberal-capitalism of the West, proposing a renewal of Christian civilization as a whole. Hence his encyclicals speak as much about material realities[5] as they extol eternal mysteries[6]. All his interventions had a great liberating force; but perceiving the dark side of freedom at work inside the Catholic Church he also set about disciplined extremist theologians[7] and eventually restored Vatican to its preeminent position of moral and spiritual leadership.

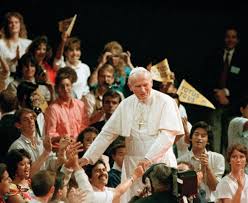

Pope John Paul II became one of the most charismatic and influential leaders in our multi-cultural century. One of the most-travelled world leaders in history, the Pope-mobile and the kissing of the ground in the land he set foot on became two touching features of his pastoral journeys.[8] Over the years at the Vatican, he welcomed a great number of world dignitaries, and the most unlikely ones at that.[9] A brilliant linguist, and blessed with an uncommon sensitivity to the human person, he made Christ known urbi et orbi, formulating the thinking of the Catholic Church in a modern lingo, without compromising on principles.[10] No doubt he often received bouquets and brickbats either from progressives[11] or from conservatives and traditionalists[12]; but he treated them all with the same solicitude.

Pope John Paul II himself was perhaps a curious mix: by and large a conservative in faith and morals and a progressive in social and economic issues. He was a bold and innovative thinker[13] and, unlike most predecessors, who were reticent, he was also a prolific speaker and writer. His book Crossing the Threshold of Hope (1994) addressing major theological concerns of today became an international bestseller and further established him as a great intellect and teacher of our times. This divine spokesman had the ability to reach out to the flock, especially the youth and families. Perfectly at home with the modern media of communication, Time magazine named him the Man of the Year in 1994, while the people considered him the ‘Pope of the Century’ or even the ‘Pope of Popes’.

Pope John Paul II died a century upon the preliminary rumblings of communism, his bête-noire, and eve of the vigil of the Feast of Divine Mercy,[14] a prominent theme of his pontificate. Six years later, his beatification overshadowed communist-sponsored May Day,[15] vindicating his earthly mission; it also coincided with the said Feast whose great Promoter he had canonized. One can read in this divine esteem for the continual efforts that the Pope had made to spiritualize the world with the cult of saints and the message of mercy, peace and love. Significantly, the forgiveness that Pope John Paul II sought in the year 2000, for arguable ‘wrongdoings’ of the historical Church,[16] symbolized an earnest desire to enter the third millennium with a clean slate.[17]

Today, there is no longer room for scepticism; it is clear that God had designed that KJW with his unique background should be Pope, and that, in a globe fragmented by religious and political stances, he should speak in diverse yet not contradictory voices; when faced by hatred and strife, be unequivocal yet mellifluous; and, challenged by a humanity fast losing its religious sense, clinical in his assessment yet warm in his approach.

Endnotes

[1] He lost his mother at 8, his only brother at 11, and his father at 21 years of age.

[2] As a key figure at the II Vatican Council he became much better known internationally.

[3] Pope John Paul II (18/05/1920–02/04/2005) reigned as the 264th Pope from 16/10/1978- 02/04/2005. His was the second-longest pontificate after Pius IX‘s 31-year reign.

[4] On 13/05/1981, Pope John Paul II was shot at in St. Peter’s Square by a Turkish gunman in the employ of the Bulgarian communist government. He recovered, resumed his work, and forgave his would-be assassin. In 1982, there was a second attempt, at Fatima, just a day before the anniversary of the first. In 1984, he consecrated the world (and not Russia, as per the Message of Fatima) to Mary. Also see his encyclical Redemptoris Mater (Mother of the Redeemer), 1987.

[5] Laborem Exercens (On Human Work), 1981; Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (On Social Concerns), 1987; Centesimus Annus (On the 100th anniversary of Rerum Novarum), 1991

[6] Redemptor Hominis (The Redeemer of Man), 1979; Dives in Misericordia (Rich in Mercy), 1980; Dominum et Vivificantem (The Lord and Giver of Life), 1986; Redemptoris Missio (The Mission of Christ the Redeemer), 1990; Veritatis Splendor (The Splendour of the Truth), 1993; Evangelium Vitae (The Gospel of Life), 1995; Fides et Ratio (Faith and Reason), 1998; Ecclesia de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist in its Relationship to the Church) 2003;

[7] Hans Kung (Switzerland), Edward Schillebeeckx (Belgium), Tissa Balasuriya (India), Leonardo Boff (Brazil), Gyorgi Bulanyi (Hungary), Jacques Pohier (France), C. E. Curran (USA), Bernhard Haring (Germany), Gustavo Gutierrez (Peru), among others, were banned for their unacceptable views on subjects ranging from papal infallibility and liberation theology to contraception. Similarly, discouraging priests and nuns from direct or full-time political activities, he ordered the American Jesuit Fr Robert Drinan to resign his office as congressman. He also excommunicated Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre for his acts of insubordination.

[8] The “Pilgrim Pope” made 104 foreign trips to 129 countries, more than all previous popes combined. He logged more than 1,167,000 km. He consistently attracted large crowds on his travels, some amongst the largest ever assembled in human history. While some of his trips (such as to the USA and the Holy Land) were to places previously visited by Pope Paul VI (the first Pope to travel widely), many others were to places that no Pope had ever previously visited.

[9] Political leaders like Mikhail Gorbachev and Yasser Arafat, among many others; and religious leaders of Christian denominations and other religions.

[10] Besides fourteen encyclicals, Pope John Paul II has to his credit several apostolic letters, exhortations, and books. Mention must be made of two significant publications under his tutelage: the Code of Canon Law (1983) and the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1997).

[11] They were critical of the Pope’s stance on artificial contraception, abortion, euthanasia, pedophilia, homosexuality and the ordination of women.

[12] They were critical of the Pope’s support to the II Vatican Council and its liturgical reforms as well as of his ecumenical efforts and inter-religious dialogue, whose supreme example was the meeting of world religious heads, which Pope John Paul II organized in Assisi in 1983. They also accused him of promoting Modernism, condemned as the “synthesis of all errors” by Pope Pius X.

[13] For instance, in Love and Responsibility (1960), which perhaps became a basis for Pope Paul VI’s Humanae Vitae, KJW dismisses the “utilitarian” view of sex for pleasure and the “rigorist” idea of sex for procreation. Instead, he sketched out a high doctrine of sexual intercourse as mutual self-donation. In his Theology of the Body (2006) Pope John Paul II broke new ground, inaugurating what many regard as a revolutionary shift in Catholic doctrine and sensibility.

[14] Pope John Paul II instituted this feast when he canonized Sr. Faustina Kowalska in the year 2000. It is now celebrated on the Sunday after Easter.

[15] Labour parades were cancelled in Poland in view of the Beatification.

[16] As the world crossed into the third millennium, Pope John Paul II magnanimously apologized to Jews; Galileo; Muslims killed by the Crusaders; victims of the Inquisition, and almost everyone who may have considered themselves victims of history. He also included the involvement of Catholics in the African slave trade; denigration of women; the burnings at the stake, and the indifference of many Catholics during the Holocaust.

[17] See the Apostolic Letter Tertio Millenio Adveniente, in preparation for the Jubilee Year 2000.

(Renovação, Vol. XL No. 9-10, 1-31 May 2011)