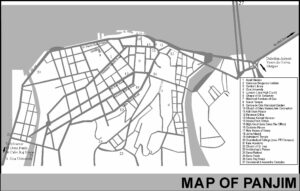

In the 1960s and 1970s, Panjim was the picture of calm and sweetness, of simplicity and decorum. The city stretched from Ourém Road up to the Military Hospital in the east-west direction and from the riverine avenue up to Altinho and Batulém in the north-south line. As a garden city on the water’s edge, its rhythm paced by the gentle Mandovi, Panjim had an identity and a charm all its own.

When I was a child, I lived in the heart of Panjim, next door to the centuries-old Adil Shah Palace and under the hypnotic gaze of Abade Faria. My day dawned with the chirping of birds, soon to be followed by the loud siren of the Bombay steamer docking at the Customs pier. The hustle and bustle of the passengers, the clatter of the baggage handlers and the taxis honking on Vasco da Gama Avenue (now Dayanand Bandodkar/DB Marg) roused the 40,000 residents of Panjim still wrapped in sleep, reminding them of their morning tasks, especially of school.

It was now as if the frenzy of the Indian metropolis had disembarked in the Goan capital! The din quickly drifted to the main arteries, Dom João de Castro Avenue and Afonso de Albuquerque Street (now Mahatma Gandhi Road/MG Road), where the bureaucracy and business establishments were situated. Upon the departure of that steamer midmorning, the city regained her composure; she lunched and enjoyed her siesta, and by 4 o’clock resumed her daily battle, which ended around 8 in the evening.

Panjim enjoyed an organic lifestyle only a wee bit different from that of the countryside! Hot bread and fresh fish went door to door; and at the municipal market they sold local produce from villages nearby. But it wasn’t only about what the people bought; it was equally about what they thought – about how they treated one another and the surroundings. They displayed civic sense and were a God-fearing lot. That church, mosque and temple were practically on the same street spoke volumes of communal peace and harmony in the city.

A Japanese writer once labelled Panjim the ‘most unIndian of all Indian cities.’ In his mind’s eye he probably saw an urban landscape devoid of skyscrapers, filth, and chaos. But had he perhaps noted the spiritual architecture of the citizenry? Panjimites were not caught up in a rat race; they lived modestly and contentedly, fearing none, much less the police, a ramshackle force anyway! Burglary was rare, and murder or suicide almost unheard of. Conscience and benevolence – or better, munisponn (humanity, in Konkani) – reigned. In the words of a fado (Portuguese folk song): ‘If someone humbly knocked at our door, they would sit with us at table; and even in the poor comfort of our home, we had loads of affection to offer.’ In short, the townsman didn’t need much to brighten his existence.

Panjim was all things to all people: a nature lover’s dream, a pedestrian’s delight, a balm for a troubled mind. There were open spaces and colonnaded footpaths. Traffic was simple and light – motorcycles, bicycles, even bullock carts, and automobiles ranging from the popular Volkswagen to the luxurious Cadillac. These were the last of the Mohicans that had emerged, quite paradoxically, from the Economic Blockade; in a way, they denoted the Goan cosmopolitanism.

Panjim was all things to all people: a nature lover’s dream, a pedestrian’s delight, a balm for a troubled mind. There were open spaces and colonnaded footpaths. Traffic was simple and light – motorcycles, bicycles, even bullock carts, and automobiles ranging from the popular Volkswagen to the luxurious Cadillac. These were the last of the Mohicans that had emerged, quite paradoxically, from the Economic Blockade; in a way, they denoted the Goan cosmopolitanism.

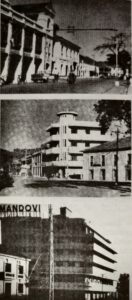

Panjim was unique; it prided itself on single items: on one daily in Portuguese (O Heraldo) and in English (The Navhind Times); on a radio station (All India Radio) and a music academy (Academia de Música) which had nowhere to hold its annual concert other than at the only public hall (Institute Menezes Bragança). Likewise, Panjim was proud of its one and only three-star hotel (the Mandovi), of its ice-cream shop (Eskimo), and its South Indian restaurant (Shanbhag). Just one cine-theatre (Nacional), one bookstore (Singbal), and one public library (Central) catered to its citizens. For their healthcare needs, they went to the medical college hospital (Escola Médica). Panjim’s children depended on one public ground and football stadium (at Campal) and its adults on their Hyde Park (Azad Maidan) to go to yell their guts out. And children and adults alike enjoyed the evening breeze at the municipal garden (Garcia de Orta).

The quiet beauty of that public garden, the city’s oldest and largest, is etched on my memory: as kids, we jumped there with excitement while our elders bantered back and forth, comfortably seated on self-appointed, gender-segregated benches. From the bandstand, where the navy orchestra and others performed occasionally, I remember naively shouting slogans (“Tujem mot konnank? – Don Panank!”) in the runup to the Opinion Poll in 1967! There were cafés and bars, taverns and little gaming houses thereabouts; and some distressing sounds of tu-tu-main-main at a nearby newspaper office always wafted into the garden. None of this must have ever solved the city’s problems of scarcity and costliness, of poverty and drunkenness! The latter two could be starkly seen in a fringe area dubbed Tambddi Mati (Red Earth), thanks to its untarred alleys and the little red lights on its porches.

Panjim, therefore, was no garden of virtues. Its relative insularity had prompted me to leave for a city abroad – I was peeved about being everybody’s business – until I changed my mind fearing that, meanwhile, my city would become another Mumbai – like nobody’s business! At any rate, the city had already started to expand westward into Miramar and Dona Paula while apartment blocks were quietly replacing houses in the city centre. There was a bridge on the Mandovi and a bus stand in the middle of the Pattó marsh; on the other hand, the sewer network lay incomplete, power outages were common, and piped water was restricted. Pure air was no doubt a saving grace; but then again, in the rains, Panjim would suddenly become Venice!

Panjim was petite, yet many of its sites stayed put on my bucket list. The stairways to Alto dos Pilotos and Escadinhas de Pedras Soltas resembled picture-postcard Lisbon – except for their state of disrepair. The likes of Saraswati Mandir, a library from the post-Republican days, were dimly lit and crowded. And while Tribunal da Relação (High Court) was a charming building adjacent to my house, I never visited it, petrified as I was by the magistrates’ stern faces. In much the same way, I was awed by the Arquivo Histórico (State Archives), but its documents half a millennium old were an ocean that my little bucket could not hold.

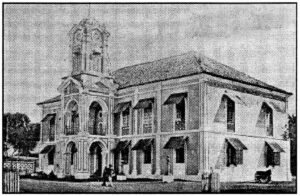

Who can ever forget the five-block Lyceum complex at Alto de Guimarães? Seniors told me that it was once reminiscent of the millennial Portuguese university town of Coimbra; but alas, the spirit had moved – only the shell remained. Worse was the fate of the Senado de Goa (municipal chamber), a distinctive building with a clock tower and hemmed in by gardens; it was torn down on flimsy grounds, so all that one can see now is a gaping space. What’s worse, the city never again got a town hall to match. These and some other facets were thus beyond my little self.

Even so, I eventually came to love and identify myself with the city. People of different creeds lived here in mutual respect. And as though time and tide waited for ever, they happily stopped in their tracks to exchange pleasantries – not to forget that men took off their hats to ladies without ado! Time was when baptisms, birthdays, and funerals were major events; and in those pre-television days, a stroll on Miramar beach at sunset, or a ride to Campal on goddia-gaddi (horse carriage) was all it took to dispel the ennui.

The rest of the magic was left to the cultural calendar to pull off. The Carnival parade, the street dances at clubs Nacional and Vasco da Gama, and the annual quermesse (open-air fair) at Fontaínhas were eagerly awaited. The Way of the Cross wending its way from the iconic Church of the Immaculate Conception up to Paço Patriarcal (Archbishop’s Palace) at Lent; the candle procession streaming the other way around, in October; Christmas celebrations et al were sights to behold. Holi, Ganesh and Diwali brought in traditional delicacies from Hindu friends. And all of this contributed towards a sweet spirit and the joy of living in Panjim.

Forty years on, Panjim is an entertainment hub – one big casino, garish, noisy and manic – which the Covid-19 virus briefly disrupted as only Covid can. The ensuing lull, however, helped me uncover the face of my city. I began to feel a homesickness for that time in the past when we faced shortages of sorts while the world seemed to be enjoying abundant life. Today, this newfound calm and sweetness, simplicity, and decorum make me feel we were never short of anything. No wonder Panjim was the apple of the eye of every Goan worth his salt!

(First published in The Peacock Quarterly, Panjim, July 2022. Reprinted by The Goan Review, Jan-June 2023 https://online.fliphtml5.com/cmlao/eron/?1681654486031

Notes

Abade Faria, or Abbé Faria, refers to the Goan priest José Custódio de Faria (1756-1819) celebrated as ‘Father of Hypnotism’. A statue depicting him in the act of hypnotising a lady was erected in 1956.

Academia de Música (1952), now Kala Academy, was the first professional music academy in Goa, set up under the baton of Europe-trained maestro António de Figueiredo.

Adil Shah Palace was the official residence of the Portuguese viceroy/governor-general (1759-1918). It continued as the seat of government and housed the legislature (pre- and post-1961). An apt extension was built in 1970. The palace is now a museum.

Alto dos Pilotos and Escadinhas de Pedras Soltas (literally, ‘Pilots’ Height’ and ‘Loose Stone Stairs’, respectively) are two of Panjim’s many stairways. The former is located behind Fazenda (Revenue Office) building and the latter in Fontaínhas/Mala ward.

Arquivo Histórico (1595) was first curated by Diogo do Couto, co-author of Décadas, an official history of the Portuguese in Asia and Africa.

Azad Maidan, formerly Praça Afonso de Albuquerque, had a monument to the Portuguese conqueror; now rededicated to Tristão Bragança Cunha, the ‘Father of Goan Nationalism’. A Martyrs’ Memorial was added in the 1970s.

Bombay steamer was a coastal service between Goa and Bombay. Several companies ran it for a century beginning from the last quarter of the 19th century.

Campal, meaning ‘a clearing’, is the area originally developed by viceroy Dom Manuel de Portugal e Castro (1827-1835).

Central Library began as Pública Livraria (1832) and was attached to Instituto Vasco da Gama (1925-1959). Renamed Central Library in post-1961 Goa, it is now housed in a state-of-the-art building at Patto Plaza.

Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception is an iconic structure overlooking the city.

Clubs Nacional and Vasco da Gama were established in the early 20th century, the former largely sponsored by natives and the latter by Panjim-based continental Portuguese.

Economic Blockade (1954-56) imposed by the Indian Union prompted then Portuguese Goa to accelerate agricultural development, import of goods (including automobiles), and start direct flights (Goa-Lisbon-Goa, via Karachi).

Escola Médica, short for Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa (1842), was Asia’s first medical school. Located at the Palace of the Maquinezes, it added a hospital building in 1927, now the headquarters of Entertainment Society of Goa (ESG). It was renamed Goa Medical College in the 1960s and shifted to Rajiv Gandhi Medical Complex, Bambolim, in the 1990s.

Garcia de Orta Garden is named after the Portuguese Jewish botanist and author of the seminal Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas da Índia (1563). He owned an estate in the old Goan capital and had the island of Mumbai on lease from the king of Portugal.

Menezes Bragança Institute, formerly Instituto Vasco da Gama (1871-1963), is regarded as one of Goa’s finest cultural institutions.

O Heraldo, founded by Messias Gomes, in 1900, was the first daily published from the Portuguese colonies; now Herald, published almost exclusively in English, since 1983.

Opinion Poll, the first of its kind in India, was held to ascertain the wishes of the then Union Territory of Goa on the proposed merger with Maharashtra. The popular, anti-merger slogan meant: ‘Your vote?’ – ‘For Two Leaves, for sure!’

Paço Patriarcal, or Patriarchal Palace, is the official residence of the Archbishop of Goa and Daman, who holds the title ‘Patriarch of the East Indies’.

Saraswati Mandir, on 18th June Road, is one of the many libraries set up by Hindu trusts in the new era of political and religious freedom under the Portuguese Republic (1910).

Senado de Goa (1511) was set up on the lines of the municipal senate of Lisbon.

The Navhind Times, founded in 1962 by mining magnate Vasantrao Dempo, is the first English-language daily to be published from Goa.

Tribunal da Relação (1544), had jurisdiction over the Portuguese Eastern Empire (Africa to Japan). It was downgraded to a Judicial Commissioner’s Court under the Indian Union and became a Bench of the Bombay High Court in 1982.

Well penned Oscar …

An insight to the present generation of the Panjim that was …

A window into my besieged city’s blissful heydey. Exceptional homage, senhor

How simple life had been when humans were content with the bare minimum and yet the Happiness quotient was so high. Oscar you have gone into every small detail and shown the present generation how much we the older generation miss the past.

It’s sad, how the City planners have no clue to save our beautiful heritage. We’re left at the mercy of these unapologetic and unsympathetic administrators who choose to do nothing constructive.

Oscar thank you for sharing your vivid experiences for our former glory.

Those were the days we all enjoyed in Goa. We will never get them back again however much we try with all the efforts. I was only 14 years old when Portuguese finally bowed to the pressure just to save Goa and goans under the orders of General Vassalo Silva the then Governador de Goa and in common understanding with the then Arcebispo Dom Jose Alvernaz.

May God give them eternal rest in heavenly abode. I had completed my studies till segundo grau and was in Pilar seminary and had watched the full episode of the war as the seminary was on the hillock which gave good view of Dabolim Airport, Marmagoa harbour and Bambolim Emissora de Goa, how the last plane flew out of Goa, how the only ship fought and how the indian airforce jets were bombarding the radio station sending chill within us as the jets were encircling our seminary while our community mass was on. This was te first time we saw what war like. The memory will never fade from my mind until death.

Your description of Panjim is just wonderful.

Óscar…only you could write like this. Your pen is magic in your hand. Your touching descriptions evoked strong memories of my own, of my 3 years in Panjim between 1976-79.

This article will preserve the information you presented.

Your description almost feels like I am reminiscing myself! Many if not most of the memories are mine too, the Bombay ‘Steamer’ the benches at the Garcia de Horta, I could almost write the names of the folks who sat there most evenings!! The gentlefolk meeting and greeting, the sedate pace of life, the fact that one actually knew each other !!! Contrast that with today !

Óscar, I am thankful to you for the memories of the Panjim of our younger days – simple, quiet, friendly, warm, the entire city lke home. It is a tragedy that (some of) its own are, by their acts of commission and omission, proving to be unworthy of their inheritance. The prospect of seeing the disfigured face of a loved one is terrifying. For as long as I can, I would rather live with the memories than with the reality, a reality that seems to have found a place on a slippery slope.

My very Best Wishes for the continuation of your multiple efforts for the good of our Land.

I wish I was born during that period, to experience Panjim the way it was.

Lovely memories.

Those old days of our beautiful Panjim City are meaningful to me as well, we can only cherish those memories. Antonio Fonseca, you have to excuse me to use this space to express my thoughts about Goa and Goans. Here is my take: That was an excellent “Recordações das memorias” by Oscar de Noronha. Just to make my note short I would bluntly say Goa is lost forever. Here’s my story. I am from Taleigao which is a backyard of Panjim. Born in 1953 and lived in Goa until year 1996(43 years). I was lucky enough to escape my life and threats to my family from fellow Gaonkars for not taking sides with their political decisions from 1978 until 1996 after the fall of Dr Sequeira from politics in 1978, what followed was political ambitions. Dr Jack Sequeira represented Taleigao, St Cruz and Merces. I was active since 1978 in educating people in my village about importance of selecting respectful candidates to represent my village and always failed. I participated from year 1978 until 1996 which sums to 18 years. Finally had to put my hands in the Air and was lucky to land in Toronto, thanks to my brother-in-law David Paes who was already in Canada.

My activities in short: Always supported Dr Jack Sequeira from 1962 until 1978. Initially it was the Congress wave that got rid of Dr Sequeira in 1978, after that it was a roller coaster with incumbents changing every 5 years. This period from 1978 until 1996 was a very tense period for me personally since I worked for loosing candidates, always challenging the people’s choices. During 1978 elections, I called all contestants for a meeting including Dr Sequeira at Casa do Povo in Taleigao to understand their purpose of contesting especially against Dr Sequeira and I must admit, I was blunt in calling them useless rogues, I had no diplomacy then, fresh from University at age 25. Anyone reading this can always confirm about my activities.

It was a no brainer to realize that moral architecture of Goans was eroding since 1978. I happened to refresh my memory of Panjim Dockyard, opposite Custom House when I arrived into the port of “Prince George in the Bahamas” I thought I reached Goa Docks in Panjim. Google it for a feel and given an opportunity do visit “Prince George Docks in the Bahamas” to refresh your memories of Panjim Jetty. My salute to Oscar Noronha for penning those memories.

thank you for this. You are keeping beautiful memories alive, and the next generation can see what we experienced.