Mariano Saldanha: um distinto académico goês

Ao conhecer um grande senhor nascido apenas duas décadas após a Revolta dos Cipaios[1], senti a corrente do passado transitar suavemente para o presente. Esse notável goês, que emigrara para Portugal no ano da Grande Depressão, passou os anos de jubilado em Goa e faleceu após Portugal ter reconhecido formalmente a conquista indiana da sua terra natal. Era quase centenário, porém, isso é o mínimo que se pode dizer de alguém que marcou na história de várias outras maneiras.

Primeiros anos

Mariano José Luís de Gonzaga Saldanha, vulgo Mariano Saldanha, nasceu em 21 de Junho de 1878, filho de Luís José António Assis André de Saldanha, de Ucassaim, e de Ana Joaquina Ermelinda da Pureza e Dias, de Socorro. Era médico que se fez indologista e pesquisou a história, língua, literatura e cultura indo-portuguesas. Era sobrinho de dois irmãos padres, Joaquim José Santana de Saldanha, fundador de uma escola na aldeia, e de Manuel José Gabriel de Saldanha, professor do Liceu de Nova Goa e autor da clássica História de Goa[2], em dois volumes.

Em 1905, Mariano Saldanha formou-se em medicina e farmácia pela antiga Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa e depois trabalhou como médico em Goa e a bordo de navios. Entretanto, sentindo-se vocacionado para o estudo de línguas indianas, aprendeu o sânscrito com monsenhor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, na Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, e frequentou cursos na Escola Colonial. Na época de Herculano em Portugal, e de Cunha Rivara e de Dalgado em Goa, não era raro um profissional do ramo da ciência interessar-se pelas humanidades; contudo, no caso de Mariano Saldanha, a mudança foi total.

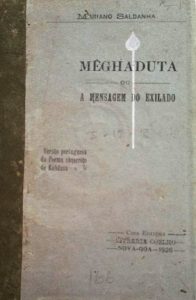

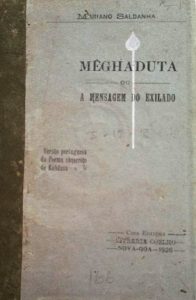

Em 1915, foi nomeado professor de marata e sânscrito no referido Liceu. No ano seguinte, publicou O Curso de Sânscrito Clássico,[3] que compreendia o seu discurso inaugural sobre a importância desta língua e os documentos relativos à criação do curso em questão. Em 1926, traduziu o poema Mêghaduta, ou a mensagem do exilado,[4] de Kalidasa, poeta e dramaturgo da Índia antiga, anotado, prefaciado e acompanhado do original sânscrito.

Docente em Lisboa

Em 1929, Mariano Saldanha mudou-se para Lisboa, agora como professor de sânscrito na sua alma mater, ocupando o lugar que ficara vago desde a morte de monsenhor Dalgado em 1922. Trazia ao povo português uma mensagem de amizade de Rabindranath Tagore, Prémio Nobel da Literatura, quem visitara em Shanti-Niketan em 1927, atraído pela ideia de harmonizar a cultura indiana antiga com ideias internacionais. Após a morte do grande poeta e pedagogo bengalês, Saldanha recordou o encontro na memória que publicou com o título “O Poeta de uma Universidade e a Universidade de um Poeta”[5].

Em 1946, Mariano Saldanha era nomeado subdirector do Instituto de Línguas Africanas e Orientais da Escola Superior Colonial, onde veio a leccionar o sânscrito e o concani até se aposentar em 1948. Publicou a Ultima Lectio[6], e depois da jubilação, um manual, Iniciação na Língua Concani, “especialmente organizado para o ensino, de carácter prático, da língua concani” na referida Escola.[7]

Voltou a Goa em 1950, onde permaneceu cerca de quatro anos, tendo sido depois convidado pelo Governo da Metrópole a participar na elaboração de um projecto de ensino público em concani, para Goa, e na transmissão de programas radiofónicos nessa língua para a diáspora goesa na África Oriental Britânica e no Golfo Pérsico.[8]

Aproveitou a oportunidade para continuar as suas pesquisas na capital.

Concanista de renome

Além de docente, Mariano Saldanha foi um investigador de renome, principalmente como concanista, ou seja, na ‘Concanologia’[9]. No 50.º aniversário da morte do ilustre estudioso, cumpre recordar o seu precioso contributo para os estudos da Língua Concani, que tanto amou e pela qual tantos esforços despendeu.

Dedicou-se sobremaneira à pesquisa fundamental da língua da sua terra natal. Visitou bibliotecas, arquivos e museus de Goa, Lisboa, Évora, Braga, Paris, Londres e Roma, vasculhando livros e manuscritos, à procura da mais pequena pista. Escreveu exuberantemente, com artigos em revistas científicas e em jornais.

Em 1936, escreveu uma valiosa história da gramática concani, no Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, que se destacou também pelo pioneirismo.[10] Em 1943, escreveu uma série de artigos sobre “Questões do Concani”, no Heraldo, um diário panginense.[11]

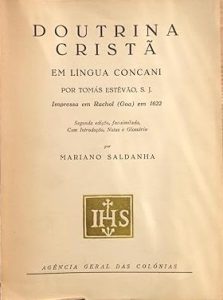

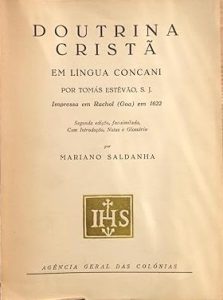

Em 1945, publicou a 2.a edição, fac-similada, com introdução, notas e glossário, de Doutrina cristã em língua concani (1622)[12], de Thomas Stephens, missionário jesuíta britânico, que foi o primeiro inglês a chegar ao subcontinente indiano e pioneiro no estudo das línguas indianas.

Em 1950, descobriu três códices na Biblioteca Pública de Braga, a saber, n.os 771, 772 e 773. As primeiras duas relatam, em concani, histórias tiradas das epopeias indianas, respectivamente, o Mahabharata e o Ramaiana; o último contém três dezenas de poemas em marata, também da mesma fonte; e todos eles escritos em caracteres romanos.[13] Prontamente informou outros interessados, inclusive um dos seus dissidentes ideológicos, A. K. Priolkar.[14]

Cultura goesa

Mariano Saldanha tinha consciência da rara singularidade de Goa, no meio do vasto subcontinente indiano, como síntese cultural do Oriente e Ocidente e detentora de um modo de vida próprio. Por isso, em 1947, mal que sentiu soprar os ventos da mudança política, o seu profundo amor à terra natal levou-o a dar um sinal de alerta.

Fê-lo primeiro por meio de um ensaio intitulado “A lusitanização de Goa”, na revista Rumo.[15] Em Goa, a Repartição de Estatística e Informação reimprimiu-o,[16] e em Portugal, a Agência-Geral do Ultramar traduziu-o em grande parte para o livro Portugal Overseas and the Question of Goa[17]. Ainda hoje é muito citado.

O douto professor sentiu-se feliz como presidente da 5.a edição do Konkani Porixod, conferência a nível pan-indiano, realizada em Bombaim, em 1952. O seu «Odhiokxachem Bhaxonn»[18], ou discurso presidencial, foi publicado em caracteres latinos, que recomendava para o concani moderno. Nessa ocasião afirmou que o concani é uma língua independente do marata e que deveria ser o veículo de instrução primária em Goa.

A propósito do referido Porixod, deu largas ao seu conceito histórico da língua concani, na memória intitulada “A língua concani: as suas conferências e a acção portuguesa na sua cultura”, publicada no Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama.[19] Duas décadas antes abordara esse tema no IX Congresso Provincial de Goa[20].

Nesta fase da vida, expressou-se também sobre a música ocidental em Goa[21]; sobre a imprensa seiscentista aí estabelecida, pioneira na Ásia[22]; e sobre a literatura purânica cristã[23], frisando sempre a identidade marcante de Goa.

Os seus trabalhos retratam-no como investigador escrupuloso, crítico exigente e polemista temível.[24]

Últimos anos

Em 1958, Mariano Saldanha voltou de vez ao solar da família e à aldeia natal que ainda mantinha o charme rústico de outrora. Aceitou como facto consumado o desfecho que teve o conhecido Caso de Goa e, em 1967, regozijou-se com o resultado do Opinion Poll, ou referendo. Infelizmente, na vida particular, foi, por um lado, vítima das leis de expropriação do período pós-1961, e por outro, privado das suas últimas economias que havia confiado ao seu antigo empregado em Portugal. Para agravar, saiu prejudicado na reforma devido ao novo contexto político.

Apesar disso, a vida continuou. Com excepção da gota e da surdez, gozava de boa saúde e manteve-se lúcido até ao fim da vida. Escrevia para os órgãos públicos, recebia visitas e aceitava convites para reuniões académicas e outras. E ainda na provecta idade, costumava celebrar o seu aniversário, cercado de familiares e amigos da velha-guarda.

Manuel Leitão, filho do seu antigo cuidador Francisco, recorda-o como um católico devoto, de coração bondoso e leitor assíduo de jornais da língua portuguesa (O Heraldo e A Vida), concani (Vauraddeancho Ixtt, Sot e Uzvadd) e marata (Gomantak), de entre os publicados em Goa. Mantinha relações com os respectivos directores e colaboradores, e no interesse destes, e ansioso por estabelecer padrões elevados, corria com tinta vermelha os jornais concani.

O erudito era consultado em assuntos relativos a Goa e ao concani. Não admira que a sua rica biblioteca com centenas de livros, microfilmes e manuscritos, tivesse atraído jornalistas e investigadores, entre os quais Carmo Azevedo, que, escrevendo no mensário Goa Today, o apelidou de “enciclopédia viva de coisas goesas”[25], bem como os activistas do Konkani Bhasha Mandal. A família doou o acervo ao Xavier Centre of Historical Research, de Goa.

Apesar das cãs, o bom e velho solteirão era paciente com os jovens. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho deleitava-se com o saber e a sagacidade do seu tio-avô. Graças à sua prodigiosa memória, este contava-lhe prontamente histórias sobre Akbar, Xivaji e outros vultos indianos, que faziam parte dos currículos escolares do pós-1961; e ela incluía-as nas suas provas.

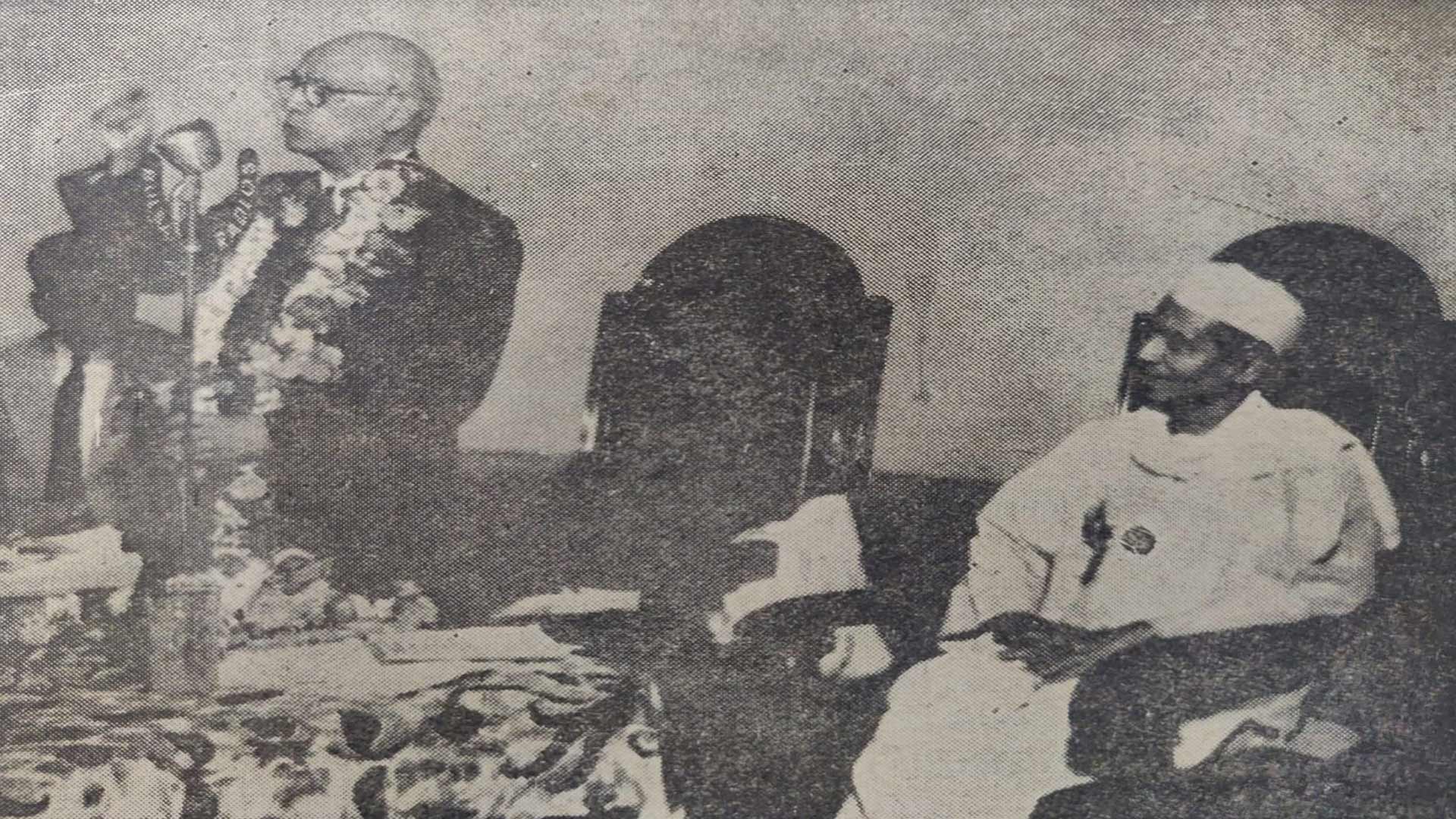

Tive eu, como menino de 6 anos, o meu primeiro encontro com o professor já então nonagenário. No Hospital do Asilo, em Mapuçá, havia ele discursado e descerrado o busto do Dr. Ernesto Borges, seu sobrinho-neto, oncologista de renome mundial e que cedo pagou o tributo à morte. Foi um momento emocionante. Eu acompanhava a minha tia Maria Zita da Veiga, que havia experimentado o seu toque curativo. Após a cerimónia, perguntaram ao professor se se importaria de esperar um pouco mais pelo transporte para casa. Impressionou-me a sua resposta: “Claro que me importo”. E logo a gargalhada que se seguiu desdizia tudo….

É impossível dizer tudo de uma vez sobre Mariano Saldanha, distinto académico goês que muito honrou a sua terra. Faleceu em 23 de Outubro, mês Mariano, do ano de 1975, quase desconhecido das novas gerações e um tanto esquecido pelas velhas. Deve ser, porém, evocado com gratidão e estudado com atenção, tal como todos os vultos da nossa terra, para que se facilite assim uma transição harmoniosa do passado para o presente.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 37, Novembro-Dezembro 2025, pp. 33-37)

Referências

[1] Revolta armada, realizada entre os anos de 1857 e 1859, em oposição ao domínio britânico, a qual de Meerut passou para Delhi, Kanpur e Lucknow, cidades no norte da Índia.

[2] 2.ª edição. Nova Goa: Edição da Livraria Coelho, 1925-26. A primeira edição intitulava-se Resumo da HIstória de Goa, publicada em 1898, em um único volume.

[3] Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1916.

[4] Nova Goa: Casa Editora Livraria Coelho, 1926.

[5] Revista de Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa, N.º X, 1943, pp. 57-77.

[6] Anuário da Escola Superior Colonial, Ano XXIX, 1947-48, Lisboa, 1948. Também nos Estudos Coloniais, Lisboa, Vol. I, 1948-49.

[7] Parte I: Noções Gramaticais. Lisboa: 1950. Não consta que tenha saído a Parte II.

[8] “Mariano Saldanha: a centenary tribute”, de Teotónio R. de Souza, in Indica, Vol. 15, N.º 2, Setembro de 1978, pp. 135-138.

[9] Termo por ele cunhado para se referir às “publicações relativas ao concani”, veja-se Monsenhor Dalgado. Esboço bio-bibliográfico. Lisboa: 1933, p. 11.

[10] "História da Gramática Concani," Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 8 (1935–37), pp. 715-735.

[11] Heraldo, de 14, 16, 24, e 30 de Março de 1943.

[12] Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1945.

[13] Os códices ora encontram-se na biblioteca da Universidade do Minho, veja-se The Old Konkani Bhārata. Volume 1: Introduction, de Rocky Miranda (Margão: Asmitai Pratishthan, 2019), p. xi.

[14] Mais tarde, Panduronga Pissurlencar, José Pereira, António Pereira, Lourdino Rodrigues, Rocky Miranda e outros serviram-se dos mesmos códices para os seus trabalhos de pesquisa.

[15] Rumo, Revista de Cultura Portuguesa. Ano 1, Agosto e Setembro, 1946, pp 343-366

[16] No. 6 da série da Colecção de Divulgação e Cultura.

[17] Lisboa: Agência-Geral do Ultramar, s.d., pp 41-58

[18] Konknni Porixod. Panchvi Boska. 1952. Odhiokx: Dr. Mariano Saldanha, Hachem Bhaxonn. (Mumboi: Fr Napoleon Silveira, 1952) É o único texto seu expresso inteiramente em concani.

[19] N.o 71, 1953.

[20] Congresso Provincial da Índia Portuguesa (Nono), Nova Goa: Tip. Bragança, 1931.

[21] “A cultura da música europeia em Goa”, Separata da Revista do Instituto Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos, Vol. VI (1956).

[22] “A primeira imprensa em Goa”, Separata do Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama, N.º 73, 1956.

[23] “A literatura purânica cristã e os respectivos problemas linguísticos e bibliográficos”, Separata do Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama, N.º 82, 1961.

[24] Veja-se As investigações de um gramático (Lisboa: Tip. Carmona, 1933), em que escalpela a obra Elementos gramaticais da língua concani (Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1929), de José de S. Rita e Sousa, antigo professor da Escola Superior Colonial; e Aditamentos e correcções à monografia O Livro e o Jornal em Goa (Bastorá: Tip. Rangel, 1936) e Ainda a monografia O Livro e o Jornal em Goa (Bastorá: Tip. Rangel, 1938), nas quais interpela o professor liceal Leão Crisóstomo Fernandes.

[25] “A Date with Dr. Mariano Saldanha”, in Goa Today, p. 13.

A Distinguished Goan Scholar

After one has met a grand old man born just two decades after the Sepoy’s Mutiny, history cannot but look like a thing of the present. He migrated to Lisbon in the year of the Great Depression. He spent his post-retirement years in Goa and died several months after Portugal formally recognised the Indian takeover of his native land. He was a near-centenarian, but that is the least of his claims. He made history in more ways than one.

Dr. Mariano Saldanha (1878-1975) of Ucassaim was a physician-turned-indologist who studied history, language, literature, and culture. He was the nephew of Fr Gabriel de Saldanha, the author of the classic História de Goa. In 1905, he graduated in medicine and pharmacy from Goa’s iconic medical school. After a few years of professional practice, he left for Portugal to study Sanskrit under Mgr. Dalgado at the University of Lisbon. It was not unusual then for a man of science to show an interest in the humanities, but his was a total switch.

On his return in 1915, he taught Marathi and Sanskrit at the Panjim Lyceum and translated Kalidasa’s Meghaduta into Portuguese. In 1929, he was back in Lisbon, now a professor of Sanskrit at his alma mater. He proudly carried a message of friendship to the Portuguese people from Tagore, whom he visited in Shantiniketan. In 1946, he was appointed as the deputy director of Escola Superior Colonial’s Institute of African and Oriental Languages. He taught Konkani there until his superannuation in 1948.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

On the milestone anniversary of this distinguished scholar, we recall his precious contribution. Mariano Saldanha’s affinity to history and languages was evident from an early age. He pursued fundamental research in the Konkani language in Lisbon. He spent countless hours in libraries, archives, and museums, sifting through books and manuscripts with a scrupulous eye for the smallest clue.

In 1945, Professor Saldanha produced an annotated facsimile edition of Thomas Stephens’ Doutrina cristã em língua concani (Christian doctrine in Konkani, 1622). In 1950, he unearthed sixteenth-century Konkani and Marathi manuscripts in Braga’s public library. The love of truth drove him forward not only to discover but also to share the fruits of his discovery. He did so even with his ideological dissenters, such as A. K. Priolkar.

In 1952, Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth Konkani Parishad. Being a strong votary of Konkani in the Roman script, his address was published accordingly. Curiously, this is his only text written in Konkani. When he sensed the political winds of change, he began to emphasise Goa’s distinctiveness in the Indian subcontinent, through its language, Konkani; the Lusitanian influences on its culture; the roots of Western music; its pioneering printing endeavours, and its Christian Puranic literature.

After his death, his family gifted his large book collection to the Xavier Centre of Historical Research. His microfilms and manuscripts show his discipline and patience. He was a member of several academic bodies and published his writings in journals and newspapers. They depict him as a thorough academic researcher, an exacting reviewer, and a formidable polemicist.

However, nothing prevented the good old bachelor from being patient with the youngsters. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho told me of how she used to lap up information and pearls of wisdom from her granduncle. While, thanks to his prodigious memory, he recounted stories with ease, she happily fit those anecdotes about Akbar, Shivaji, and other Indian greats, in her school answers.

At age 6, this writer had an unforgettable first encounter with the then-nonagenarian professor. He had unveiled the bust of world-renowned oncologist Dr. Ernest Borges, his grandnephew, at Asilo Hospital, Mapuçá, and addressed the gathering. It was an emotional moment. After the ceremony, the Professor was asked if he would mind a slight delay in his ride home. His stern reply was, ‘Yes, I mind.’ But then, the delayed laughter said it all.

For their part, the citizenry today should mind that the memory of Goan notables is often taken for a ride. They deserve better from our civic, academic, and governmental bodies if we are to achieve a seamless transition from the past into the present.

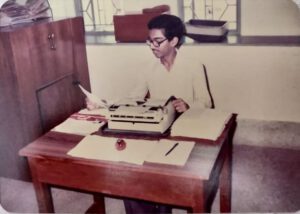

Banner: Dr Mariano Saldanha delivering the presidential address at the Fifth Konkani Parishad, Bombay, 1952

This article was first published in Herald, Panjim, on Dr Mariano Saldanha's 50th anniversary of death, 23 Oct 2025

A Life in Translation

Quasi-Memoir-1

I was clueless as to 30 September, International Translation Day, instituted two years ago. I got the lowdown from that enterprising, Herald journalist Dolcy D’Cruz: for the purpose of a feature to mark the occasion, she'd sought to know what translation meant to me and how I went about my activity.

‘Translation is a magical thing,’ I said to her, almost instinctively. ‘Not only does it help spread information and speed up business across the globe, it promotes cultural understanding.’

At the back of my mind were Tolstoy and Dostoevksy, Verne and Dumas, Anderson and Grimm, authors whose native languages I didn’t know. And I shed a tear for those who had to depend on renderings of Shakespeare, Dickens and Twain, and why not, Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse. I was lucky to read them all in the original, as I was, when it came to my father’s recommendation of a Portuguese staple diet: Júlio Dinis, Garrett, Camilo, Eça, Ramalho, Aquilino, for a novice; and my additions: Pessoa, Torga, Namora, Agustina, Lobo Antunes, and Saramago (with a pinch of salt).

Literary translations have made the world richer. And it’s not literature alone that has depended on translations; even the most disparate subjects like history, medicine and everything in between have benefited from them. If in the early twentieth century, seminarians in our archdiocese had to depend on Latin texts, it wasn’t only because that’s the official language of the Church; there were no translations available in the vernacular!

Even more picturesque was my doctor aunt’s story about the use of French manuals at the Goa medical school, as late as the 1950s: students had soon cultivated the art of reading them aloud in twos or threes, and straight in Portuguese. That was magic!

Early days

As aural memories came gushing, I began to realize that translation had indeed been an organic part of my life. As a child juggling several languages, from Portuguese and Konkani at home, to English, French and Hindi at school, oral translations happened almost as a matter of course. I would reproduce in Portuguese information that I’d received in English, and vice-versa. Mixing of lingos and literal translations were a big no-no, whereas idiomatic language was warmly encouraged.

Yet, translation per se was never the main concern; the accent was on reading good literature and relishing good conversation; it was about having a dictionary at hand and looking up the meaning of an unfamiliar word; it was about finding le mot juste. It was no cakewalk but, looking back, the long walk was so worth it. And a job well accomplished always translated into joy.

After my father’s remark, ‘Languages are an asset; master them while you’re young,’ the next best thing that stuck in my head was Bacon’s famous quote: ‘Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.’ This was like a command from on high. Or for that matter, F. J. Sheed’s dictum that ‘… minds feed on minds, you cannot nourish your mind with a chop,’ struck me as very sensible.

After handling English texts, ‘ex officio’, on school days, I would spend bits of late Sunday mornings decoding Portuguese texts under my father’s tutelage. By the end of high school, I had begun devoting an hour or so to transcribing All India Radio afternoon news bulletins for O Heraldo. And why? Now it just seems so funny: I’d found this arrangement vital since Goa’s first daily, which was on its last legs, no longer subscribed to news agencies and was starving for news. I also thought it would reassure my father who, after retiring prematurely, lent a hand at the paper – for the love of the Portuguese language and practically for free.

In the public domain

That happened to be my first stint with translation outside the domestic sphere. I didn’t think any good would come out of all that. But, three years later (1983), when I least expected it – I was in the first year of college – the then Jesuit priest Teotonio R. de Souza invited me to work as a research assistant at the newly established Xavier Centre of Historical Research of which he was the director. My task was to create summaries in English of the Mhamai Kamat papers written in Portuguese and French. I was also pleasantly surprised that he’d entrusted me two of his research papers for translation. That we argued playfully about his views is quite another matter entirely!

After my MA at the University of Bombay (1985-87) and a language and culture course at the Universidade de Lisboa (1988), I had a short stint as a lecturer in Portuguese at Dhempe College, Panjim, chiefly, to replace my father who was down with malaria. After a few months, I hesitantly took up an interpreter’s job at the Embassy of Brazil, lured by the national capital. On arriving there, however, I was stunned to see that I would be assisting an eighty year old: Pylades Prata Tibery, a Brazilian national of Greek and Italian ancestry, introduced himself as a ‘juiz de gado’ (cattle judge).

Tibery and I crisscrossed the subcontinent, by road and rail, trailing the Nellore buffalo – a breed that, according to the garrulous old man, Brazil had imported from India in the early twentieth century. Our activity was interspersed with a generous exchange of notes on European and Brazilian Portuguese. While the English of his school days was amusing, even more so were his colourful descriptions of ‘convivial society’ expressed in his native Brazilian.

Well, I could hardly be buffaloed by a more outlandish task even if handsomely paid, as indeed I was. It marked the beginning and the end of my honeymoon with translation/interpretation as a full-time job... On my return to Goa, I took up teaching as a career. After the initial hiccups, I found fulfilment in interpreting my students’ thoughts and feelings, and translating their ignorance into knowledge, their anxieties into hope, and their ambitions into reality! Translating and interpreting could now only be side gigs, mostly to oblige friends and family. For instance, I liaised at a couple of wine festivals and carried out humdrum legal translations, among other things. Even these I could no longer endure when I finally had my eyes set on translating literary, historical and spiritual texts. That would surely be a balm to my spirits.

Literary translation

Sometime in 1995, a brief encounter with Editor Arun Sinha of The Navhind Times provided that go. Keen on setting up a literary page to step up his paper’s Sunday magazine, ‘Panorama’, he suggested I work on Goan short stories written in Portuguese. I did produce quite a few translations, but alas, inevitable changes on the home front constrained me to discontinue the series.

But in spite of everything, mine has continued to be a life in translation, of which the Herald article gives a glimpse (see the link below).

(To be continued)