Simple and Sublime

The Christmas tableau is a heart-warming story in miniature. As a child I was moved particularly by those poor shepherds huddled up on the cold hills of Bethlehem; they were the only ones to hear “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” that mystical night. I was also enthralled by the Magi, whose regal aura perfectly balanced out the divine narrative. After all, Jesus not only descended from the House of David, he descended from Heaven and made his dwelling among us. Here was real majesty, with no hint of extravagance.

The Christmas tableau is a heart-warming story in miniature. As a child I was moved particularly by those poor shepherds huddled up on the cold hills of Bethlehem; they were the only ones to hear “Gloria in Excelsis Deo” that mystical night. I was also enthralled by the Magi, whose regal aura perfectly balanced out the divine narrative. After all, Jesus not only descended from the House of David, he descended from Heaven and made his dwelling among us. Here was real majesty, with no hint of extravagance.

With two thousand years of the Nativity behind us, we surely have the benefit of hindsight. The multitude then perhaps failed to appreciate the wondrous event; and the few enlightened ones were so meek and mild that the likes of Herod exploited the situation, apparently frustrating God’s plans for humankind. The king and his minions even drove Christ to his death but, thankfully, his resurrection soon became the very foundation of the Christian faith.

There was a mighty coherence to Jesus’ life story. His rise from the tomb established his reputation as a Man-God. Were it not for Easter, Christmas would have gone down in history as a non-event. In fact, the Bible does not specify Jesus’ date of birth; and in the first two centuries, none paid attention to it anyway, as birthday celebrations were considered a pagan custom. Saints and martyrs were remembered on their day of death, which marked their entry into Heaven. Hence, theologically, Easter ranks higher than Christmas.

However, considering the tender feelings that birth evokes, Christmas was poised to be a cherished day. Based on patristic sources that dated Jesus’ conception (and crucifixion) to 25 March, St Hippolytus of Rome (c. AD 204) was the first to explicitly assign Christmas to its current feast day. For their part, the Romans had long been observing 25 December as Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (‘birthday of the unconquered sun’), so when in AD 325 Constantine I, the first Roman Christian Emperor, declared Christmas a holiday, the relation between the rebirth of the sun and the birth of the Son of God became more than obvious.

Half a century later, Pope Julius I formalised the date; yet Christmas would continue to be celebrated in close association with the day of Jesus’ baptism (6 January) for a long time to come. On this day some Eastern Orthodox Christians still observe Christmas side by side with the (revelation of the Infant Jesus to the Magi), while in accordance with the Julian calendar, Greek and Russian Orthodox churches commemorate Christmas on 7 January.

Celebration of Christmas struck root in the medieval ages. It gained impetus with Charlemagne’s crowning on that day in AD 800. The century also saw the creation of a special Christmas liturgy, although not on a par with that of Good Friday and Easter. But by and by Christmas developed a unique, visible identity, not least with the pine tree planted by St Boniface, as a pointer to Heaven; the old tradition of carol singing that was lent a heavenly form by St Bernard of Clairvaux; the crib, invented by St Francis of Assisi as a means of imparting the Christmas story, and so on.

Curiously, the more Christmas gained acceptance, the more it began to vary across countries, social and political eras, and Christian denominations in the post-Renaissance period. With changing values and norms, new customs were born while some of the older ones just hung on: the eye-catching star, the bright little candles, the sweet-sounding bells, and the intimate, family dinner, to name just a few elements that over time ensured that the divine occurrence became instantly relatable across cultures.

Christ’s coming was a watershed moment in the history of the human race. But the tableau typical of post-industrial society is so highly romanticised that we miss out on the chequered history and rich symbolism of the Nativity. Millions attend Mass on the world’s most prominent holiday, only to top it up with a secular, not to say raucous, celebration. Here the divine protagonist is easily forgotten and Santa the antagonist highlighted. In short, we forget the reason for the season.

With half a century of Christmases behind me, I feel more and more concerned about our collective failure to grasp the mystery of the joyous occasion. How I yearn to approach the manger with the simple heart of the proverbial shepherd and the sublime mind of the famed Magi!

(Herald, 23.12.2019)

The Last Things – First!

“In all thy works remember thy last end, and thou shalt never sin.”

(Ecclesiasticus, 7:40)

When we lose a loved one, our hearts ache and a great unease pains our sense. Wrestle how we might, we come to accept the reality only after we have decided, like Keats in ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, that to them ‘now more than ever seem[ed] it rich to die, to cease upon the midnight with no pain’. Eventually, we gratefully recognize that history had been unfolding before our very eyes through God’s infinite wisdom, mercy and goodness. Peace descends on us and the former unease turns into a wish simply to remain spiritually united with the departed soul.

Taking in the inexorable mystery of death – and, specifically, the passing away of a near and dear one – is an important milestone in our lives. Helen Keller once said apropos the proper use of the physical senses: “Sometimes I have thought it would be an excellent rule to live each day as if we should die tomorrow. Such an attitude would emphasize sharply the values of life. We should live each day with a gentleness, a vigour, and a keenness of appreciation which are often lost when time stretches before us in the constant panorama of more days and months and years to come. There are those, of course, who would adopt the Epicurean motto of ‘Eat, drink, and be merry’, but most people would be chastened by the certainty of impending death.”

Many of us would also wish to gaze beyond our earthly life, seeking to understand what is to become of us after death. And should we wonder why we are born at all if we are to die some day, we will realize that there is more to life than just this earth. It requires only that leap of faith to see that, like matter, the soul changes its form but is never destroyed; that life returns to where it has come from: the bosom of the Lord!

Communion of Saints

Catholic doctrine has comforting answers to the eternal questions of Life and Death: it would be of immense spiritual profit if we learnt them in time, so that whether or not we gain this whole, wide world, we might be poised to earn the next!

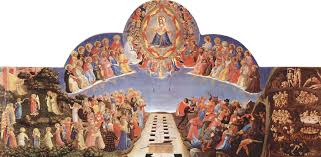

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) teaches us that, living or dead, when in a state of grace we live in Christ as ‘saints’; that there is the church of heaven and of earth, where the saints live in communion with each other and with God, much in the manner of the Triune God!

The CCC emphatically says, “What is the Church if not the assembly of all the saints? The communion of saints is the Church,”[1] and goes on to explain that the term has two closely-linked meanings: communion in holy things and in holy persons.[2]

The communion in holy things or spiritual goods comprises (1) the faith received from the apostles and kept alive through prayer; (2) the sacraments, most importantly the Eucharist; (3) the charisms, or graces that the Holy Spirit distributes among the faithful for building up of the Church; (4) our possessions, which are, really speaking, the Lord’s goods under our stewardship; and, finally, (5) love, whereby if one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honoured, all rejoice together.

The communion in holy persons refers to the life that the saints of heaven and earth live in common. While some of Christ’s disciples are still pilgrims on earth, others have died and are being purified; yet others are already in glory, contemplating God in full light. The exchange of spiritual goods, while it helps the departed to attain the Beatific Vision, also makes their intercession for us effective. Finally, being more closely united to Christ, they fix the whole Church more firmly in holiness.

In his book True Spiritualism, Fr. C. M. de Heredia, S.J., calls the Communion of Saints “a Divine Corporation, a great communism in which all the saints in heaven and all the souls in purgatory and all the children of the Church on earth form one vast family, of which Christ is the head, and participate in all spiritual goods that are in common.” The early Christians in Jerusalem “had but one heart and soul; neither did any one of them say that, of the things which he possessed, anything was his own; but all things were common to them. [...] And those who had houses and lands sold them and laid the price at the feet of the Apostles who distributed them to every one according to their needs.” (Acts 4: 32, 34) The Communion of Saints is this same idea “raised to the heavenly sphere, embracing both planes of existence, enveloping the finite world and entering into the infinite, the idea that makes common property not so much of earthly as spiritual goods.”[3]

Vocation of the Church

The CCC says, “If we continue to love one another and to join in praising the Most Holy Trinity – all of us who are sons of God and form one family in Christ – we will be faithful to the deepest vocation of the Church.”[4]

What is the deepest vocation of the members of the Church? It is to know God, love Him and serve Him. So it behoves us to learn how to do all these things! We should (re-)arrange our worldly priorities so that God becomes the centre of our lives and is forever praised in all that we do. On balance, this is what holds out the eternal reward after our life in this valley of tears!

“It has been alleged oftentimes,” says De Heredia, “that the Church has taught that in this world there is nothing but misery, and that she is not for this life but for the next. Well do we know how erroneous that is! As the soul is greater than the body even in this life, so does it follow that the pleasures of that soul are greater than the pleasures of the body. It is the Church which teaches us how to be happiest in this life and happiest in the next. The philosophy that reduces the world’s playthings to their proper perspective and makes man at once great in the accomplishments of earth and at the same time divinely indifferent to them is hers. [….] No hedonist, no aesthete, however rapturous his pagan worship of beauty, can equal the Catholic even in pursuit of earthly happiness.

“But immeasurably beyond these sources of joy, the Catholic has his firm hope in the everlasting happiness of heaven. He has his trust in a God who loved man so much that He came to earth and died for him. The light of Paradise is in his eyes. The beauty of God illuminates his soul. The caresses of his Heavenly Father are on him. And he has his belief in the power and companionship of the Communion of Saints.”[5]

Last Things First!

The communion of saints is a marvellous reality.[6] But this can be fully appreciated only against the background of eschatology, the teaching about the ‘Four Last Things’: death, judgement, heaven and hell. These apply to the individual, while the resurrection of the bodies and the final judgement at the second coming of Christ are for the human race as a whole.

Knowledge about the ‘Last Things’ is best not left for the last moment (as St Francis of Assisi says, “We shall die sooner than we expect”). We are duty-bound to see that the ‘communion of saints’, ‘the forgiveness of sins’, ‘the resurrection of the body’, and ‘the life everlasting’ from the ‘I Believe’ are not mere words but operating realities! We must understand that the ‘hour of death’ that the ‘Hail Mary’ reminds us of is not just another moment in a distant, even undefined, future but could come sooner than later! And we who recite the ‘Our Father’ and assist at Mass would do well to learn what is meant by the ‘Kingdom’ and ‘Eternal Life’! Such fundamentals of our faith have to be transferred from the tomes of theology to the homes of everybody – meditated upon, discussed, internalized, and acknowledged in our daily life. Or even a prayer, like the following one to St Joseph, composed by none other than Pope Pius X, points to the true worth of those concepts.

O Glorious St. Joseph, a model for all who are devoted to labour, obtain for me the grace to work in a spirit of penance, for expiation of my ma ny sins; to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my inclinations; to work in recollection and joy, deeming it an honour to employ and develop through labour the gifts received from God; to work with order, peace, moderation, and patience, never shrinking out of weariness and trials; to work, above all, with purity of intention and with self-detachment, having ever before my eyes death and the account that I will have to render of time lost, talents wasted, good omitted, and vain complacency in success, so baneful to God’s work.

ny sins; to work conscientiously, putting the call of duty above my inclinations; to work in recollection and joy, deeming it an honour to employ and develop through labour the gifts received from God; to work with order, peace, moderation, and patience, never shrinking out of weariness and trials; to work, above all, with purity of intention and with self-detachment, having ever before my eyes death and the account that I will have to render of time lost, talents wasted, good omitted, and vain complacency in success, so baneful to God’s work.

All for Jesus, all through Mary; all after thy example, O Patriarch St Joseph! This will be my watchword in life and in death. Amen.

This is eschatology made simple... eschatology in action! We are gently reminded that this world and the next are seamlessly woven into one whole; that what we do now – and how we live and work – determines our later fate.

It is easy to see that the Last Things are relevant not only to the afterlife but also immensely so to our present life. By letting us realize our final end, they bring about the required change in our worldview. They determine our dreams and aspirations as well as our response to earthly trials and temptations; they shape the nature of our hope and our way of life. They teach us why it is natural to seek first the kingdom of God and its justice; and how to be in the world and not of it.

It is surprising that we Catholics seldom talk actively about the Last Things. It is as though a conspiracy of silence is militating against our understanding them fully, thus even giving Eternal Life a semblance of fiction. Alas, we fail to realize that, by ignoring this real important aspect of our Christian existence, we let pessimism and despair cloud our consciousness. This is truly asphyxiating for the Catholic soul.

On the other hand, the greater our engagement with the Last Things the better it is for God’s people. A culture of hope and consolation is fostered, lending that much-needed supernatural quality to our being. We begin to live an integrated Catholic life. The communion of saints in heaven and earth is made active, and the Kingdom comes.... All good enough reasons to put the Last Things first!

(Renovação/Renewal, Goa, 16-31 August 2011)

[1] CCC 946

[2] The communion of saints is not linked to ‘spiritism’ (contact with the dead), which is disallowed by the Church.

[3] C. M. de Heredia, True Spiritualism, P. J. Kenedy & Sons, New York, 1924, p. 9-10

[4] CCC 959

[5] Op. cit., p. 28-29

[6] Whoever doubts this may refer to a simple little book, Read me or Rue it, by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P., TAN Books, 1992 (First published in 1936, with approval from His Eminence the Cardinal Patriarch of Lisbon): It carries captivating true stories about the Poor Souls in Purgatory.