Panjim Church bell strikes 150

Panjim’s Immaculate Conception Church, with its zigzag stairway and whitewashed exterior, is a major attraction. Sitting high up on Conceição Hill, it crowns the city-centre landscape to a tee. No one goes by without looking twice at the majestic edifice or stopping to hear the church bells ringing. The rich and mellow tone of the main bell is a gift to the city’s soundscape. Today marks the day when it was first heard from the belfry 150 years ago.

The bell has a long history of travel. It was cast in 1749 by João Nicolau Levachi of the Royal Foundry of Lisbon, by order of Friar José de São Patrício, Prior of the Augustinian monastery in the Rome of East. It was a perfect match for Our Lady of Grace, the city’s grandest church. In 1841, as the monasterial church was inoperative, following the extinction of the Religious Orders, Governor José Joaquim Lopes de Lima shifted the bell to the Aguada Lighthouse. The clock regulating the eclipses struck the hours on this bell. This arrangement lasted for three decades (1841-71), until it was replaced by the Argand system.

The approximately 2.25-ton bell (diameter 2 m, height 1.8 m), Goa’s second largest after the Cathedral See’s Golden Bell, was then assigned to the Panjim parish church. In a daring project undertaken by machinist António Felix da Costa of Siolim in November 1874, the bell was transported on two canoes and offloaded at Cais dos Camotins (a wharf next to the Mhamai Kamats). It was hung on two thick makeshift columns, close to the cemetery behind the church, and was first rung on the feast’s eve that year.

The work on the architectural modification of the frontispiece began in August 1875. Then came the final stage of Costa’s ingenuity. By 26 November, the scaffolding was in position. The massive bell suspended from a pulley was raised slowly to the central belfry specially built for it. The spectators were amazed. Te Deum laudamus was sung on this day as well as on 1 December 1875, when the bell was rung from the apex for the first time.

It was not just another day in Goa. Those engineering feats deserved front-page coverage, except that Goa did not have a daily. In the former capital city, now called Old Goa, preparations were underway for the third solemn Exposition of St Francis Xavier. In Panjim, the new capital, officially called Nova Goa, the city centre was almost picture-perfect, with the Senate’s imposing clock tower building, the public promenade (today’s municipal garden), and the elegant Largo 13 de Junho, now Church Square. Only Corte de Oiteiro was left to complete the scene as it stands today.

It is quite another matter that a serious mishap tarnished the third anniversary of the installation of the Levachi bell. On the evening of Sunday, 1 December 1878, the third day of the novena to the Immaculate Conception, while the bells were ringing and the faithful were exiting the church, a hook bolt of the main bell came loose and fell on a devotee, Camilo Cipriano Barreto Pereira, causing a deep cut in his skull. According to the Orlim-based weekly A Índia Portuguesa, he was a newlywed native of Raia and an employee of the Military Hospital in the city. He succumbed to his injury 10 days later.

After a few years, the clapper of the bell dislodged, killing a man, and a smaller bell fell off from the tower. In 2018, a similar tragedy was averted, thanks to the alertness of parishioners Samuel D’Silva and John Fernandes. They repaired the sagging bell shaft and the broken clapper of the main bell. ‘We researched a lot before we started on this. We examined many bell towers, particularly that of the Cathedral See,’ said fabricator Silva.

The repairs took three years. Mechanical engineer Fernandes recalled the crucial inputs received from metallurgical engineer Edgar Remedios, fabricators Maria Enterprises of Pilerne, carpenter Mahesh Vishwakarma of Panjim, Rohan Parab of Mahalaxmi Workshop, Bethora, and welding technologist Ramesh Arolkar of Poona.

Fernandes said, ‘It is a joy that with their wholehearted cooperation we were able to complete the work with precision and without any casualty, by November 2021, under the banner of the Immaculate Conception.’ The works were undertaken during the tenure of parish priest Fr Walter de Sá and Confrarias president Pedrito Fernandes.

Appreciating the iconic heritage bell, parish priest Fr Cipriano da Silva, opines that the bell has aged as gracefully as the church building itself. ‘Majestically perched almost at the pinnacle of the frontispiece, the old bell not only adds beauty but also increases the faith and fervour of the people,’ he added.

Reflecting on the bell, Fr Haston Fernandes, assistant parish priest, said, ‘A church bell is not just metal clanging to remind the faithful about an oncoming liturgical ceremony. As per the old rite, its ringing has an exorcising power over the parish. We sometimes take our bells for granted. I hope our church bell awakens us spiritually as to what it has been doing every day.’

Panjim’s white icon is now hemmed in by high-rises, yet it remains the city’s best-known landmark. People also connect with its stately bell, which has a calming effect in the midst of an oppressive soundscape. The bell is a constant invitation to heed God’s voice.

Pic credits: 1, 2 - Oscar de Noronha; 3, 4, 5 - Samuel D'Silva

This article first appeared in Herald Cafe, 30 November 2025, p. 1, and, with a few additions, at https://www.heraldgoa.in/cafe/panjim-church-bell-strikes-150/455647/ on 1 December 2025.

A Wobbly Webinar on the Goa Inquisition

A few hours ago I watched a webinar on the Goa Inquisition, subtitled “untold atrocities by St Francis Xavier and missionaries”. It was flawed from the very beginning, for although St Francis Xavier had wanted the tribunal to put an end to profligacy in the city of Goa, he died in 1552, eight years before it was established. Nor did the panelists accuse any other missionary, in the course of the ninety-minute long proceedings.

The session began with a demand that the horrors, atrocities, brutalities, cruelties, what have you, of the Goa Inquisition be made known to the world, and a museum established at the earliest. You can be sure the webinar was hardly an academic exercise, not just because three out of the four speakers there are politically affiliated, but because the so-called “online exhibition” was exhibitionist, marked by cheap rhetoric and wild exaggeration.

The only academic present on the panel quickly rattled off dates. His only argument was that the Catholics of today are not to be blamed for what happened centuries ago. He should have also brought out the nature of the tribunal; he didn't do so, yet he didn't fail to make some sweeping statements. The professor presented no counter-argument to the macabre theory developed by the organisers of the webinar; but that’s because the other speakers did not put forth any argument in the first place. They were in plain accusation mode; it was all sound and fury, signifying nothing.

When dealing with such a sensitive historical issue, one would expect at least one honest and fair-minded panelist to state the meaning, nature and functions of that much maligned ecclesiastical court of law, and let the listeners make up their minds. On the contrary, the speakers were not only highly critical, they issued summary judgements – something that the very tribunal under attack never did! The tribunal sure had shortcomings but it did follow well laid out procedures and give the accused the right to defend themselves.

Was it that the panelists did not have enough time to go into the main aspects of the Inquisition? Not at all. Going by the organisers’ track record, one would not expect them to give evidence, weigh each word as they spoke, and see both sides of the issue... And how could one expect them to lay their cards on the table? That would in fact have knocked the wind out of their sails. That would have taken the sting out of their agenda.

Mapping Goa's Architecture

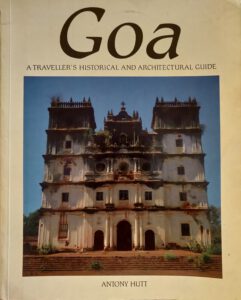

Goa - A Traveller's Historical and Architectural Guide, by Antony Hutt. Scorpion Publishing Ltd, England. Rs 200

It could well be called a serious work written for the casual traveller. More specific academic exercises have preceded this one since the 1950s but the highlight of Antony Hutt's book is his comprehensive treatment of Hindu, Christian and Muslim architecture – civil, religious and military.

Out of the nine chapters the first five are devoted to the history of Goa – right from the early times down through the Hindu and the hitherto neglected Muslim period, up to the Portuguese connection, when Goa got to partake directly of the history of the modern world. However, the 20th century is almost entirely left out.

The historical account is highly readable, largely chronological, though desultory at times. Refreshing it is to find the history of tiny Goa placed in the larger context of the history of India and the world. Hutt is well disposed towards the Portuguese, the Inquisition notwithstanding, and is of the opinion that they "inaugurated the most brilliant period in her history".

Old Goa alone becomes the subject of chapter 6. The Indian Baroque church of the Holy Spirit (St Francis of Assisi), the church of Our Lady of the Rosary, St Catherine, the Cathedral See, Grace Church (St Augustine's), the Royal Chapel (St Anthony), St Monica Nunnery, the convent of St John of God, the Minor Basilica of Good Jesus, St Cajetan, church of Our Lady of the Mount, the Viceroys Arch, and the Archaeological Museum – twelve monuments, all of them mapped. Good treatment this but no real revelations whatsoever.

The next few pages are devoted to Portuguese architecture outside the capital city. This is followed by a novel chapter on the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture.

It is in the following chapter that the author is least original in what concerns civil and religious architecture. Salcete, and more in particular, Loutulim, forms the main thrust, and what follows is a routine description of only the better known houses in Salcete – the da Silva mansion in Margão, the Miranda and Figueiredo houses in Loutulim and the Menezes Bragança in Chandor, the only exceptions this time being the Salvador Costa house in Loutulim and perhaps also the Souza Gonçalves and Albuquerque mansions in Bardez.

On the other hand, a novelty is certainly the description of the forts of Goa: Tiracol, Chapora, Aguada, Reis Magos, Gaspar Dias, Cabo, Marmagoa, Cabo de Rama and the inland fort of Santo Estevam, all find their rightful place in Hutt's book.

In contrast with the earlier chapter, what constitutes a real contribution is Hutt's elaboration of the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture. It is, however, most unfortunate that there is not a single picture of any of the six Hindu houses described – the Sinai Kundaikars in Kundai, the Ranes in Sanquelim, the Khandeparkar house in Khandepar, the Dempo and Mhamai Kamat houses in Panjim and the Deshprabhu palace in Pernem. We are only left to imagine what they really look like.

More than nine temples are included, the earliest being the rock-cut sanctuaries of the 3rd-6th centuries A.D., most of which are Buddhist in origin; Sri Mahadeva temple, Tambdi-Surla; Shiva temple (Curdi), Saptakoteshwar (Naroa); Mahalsa, Mangueshi, Shantadurga; Kamakshi (Siroda), and Mahalaxmi (Bandora). There are specific references to the "odyssey" of many Hindu deities of Goa.

Hutt was in love with Goa and visited it often from the 1970s to the 80s. He could not then possibly miss out a comment on the life of the Goan people. And the final chapter is just that, a paen to the Goan genius: the warmth and colour of the people, the traditional communal harmony, and so on. But this sociological exercise should have been accompanied by a more definite statement on the nature of popular architecture in Goa – a point that is sacrificed at the altar of elite architecture, so to say.

A good bibliography can serve as a delicious dessert for the curious mind. Sad to say, here the book is a complete let-down. The scanty information cannot satisfy even the least curious of travellers/readers. There is not even a minor reference to the works of Mário Tavares Chicó or Carlos de Azevedo from Portugal nor to the historical works of Danvers, Gabriel de Saldanha or José Nicolau da Fonseca. Rather mysterious references are made to books published after the author's death, and for that matter, other books figure in the bibliography from which not a line or illustration is traceable in the text. Also missing is a detailed map of Goa.

All in all, an impressive book. Good get-up, fine printing. For certain shortcomings of the text, every reader would be willing to make certain concessions given the author's premature death in 1985.

(Goa Today, November 1989)