Story of Mário, the Miranda (Part 2/6)

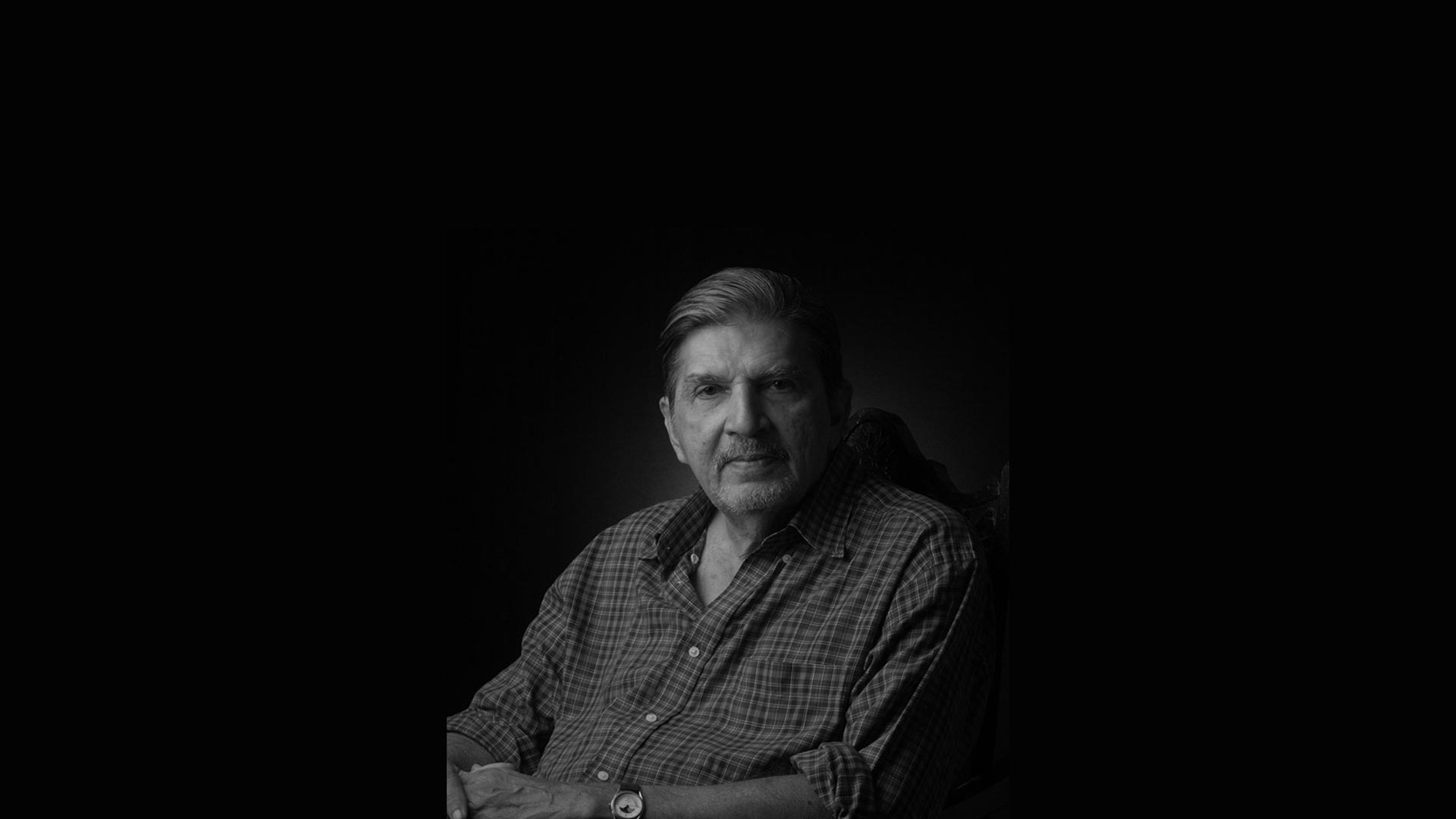

The Artist as a Young Man

The Artist as a Young Man

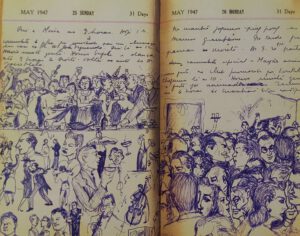

It was during his college days in Bombay that Mário’s characters first strutted out of his diaries; he drew pocket cartoons and peddled them at Flora Fountain for pin money.[11] And at a medical ball held at Clube Vasco da Gama, Panjim, couples dancing the night away delighted in the frisky sketches of the faculty members that Mário kept drawing on the wall mirrors lining the ballroom.[12]

It is not that Mário always passed uncensured. One day, a priest from the village, whom he had depicted outside the local fish market, showed up at his house. Mário’s mother, after doing her best to placate the visitor, ended up going to see archbishop Dom José da Costa Nunes, who had once expressed his wish to meet the young artist. Mário was hesitant but once there, was relieved to see his diaries spark guffaws rather than a controversy. ‘That was the first time I was appreciated by someone I didn’t know,’ he said.[13]

Mário maintained a diary right through his years spent in British India with intermittent stays in Goa and Damão (Figure 2). The last three logbooks (1949-51),[14] now available in print, are a shrine of frolicky pictures of relatives and friends in Loutulim, Panjim and Margão.[15] To quote Nissim Ezekiel, ‘the buffoonery of his human figures is redeemed from grossness by their verve, their inner urge towards going places, getting somewhere. It is not always their fault that there is no place to go, nowhere to get except through the corridors of illusion.’[16]

That was Mário’s equivalent of the dark night of the soul! His lifestyle was a cause of concern to his by now widowed mother struggling to manage the household while at the same time providing for Pedro at Princeton University.[17] But then Mário had a change of heart: was it the showcasing of his watercolours and drawings by the 1950 Souvenir of the Bombay-based Loutulenses League[18] that did the trick?

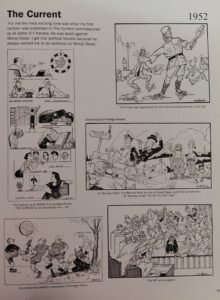

In 1951, seeing a bleak future for himself in Goa, Mário moved to Bombay. Though creative possibilities seemed unlimited here, he was jobless and quite badly off at first. That’s precisely when Policarpo (Polly) Vaz, a fellow hosteller at Rockville,[19] famously suggested to him to hand-craft picture postcards depicting the city monuments, offering to sell them at the hotel where he worked the night shift. Needless to say, the two became fast friends; and they had even thought of migrating to Brazil,[20] when Mário got a call from D. F. Karaka of The Current. The redoubtable editor, riveted by Mário’s diaries, commissioned him to cover a can-can dance scene at the Taj Hotel, and received such a rib-tickler that he promptly took him on as the tabloid’s regular cartoonist.

The young Goan created a stir in Bombay's journalistic circles when his cartoons first appeared in the press. Editor C. R. Mandy and art director Walter Langhammer soon invited him to The Illustrated Weekly of India. Before long, other Times Group publications,[21] too, began to use Mário’s drawings; they skilfully portrayed movement and sound, and often featured the cartoonist’s trademark dog.

Art of Cartooning

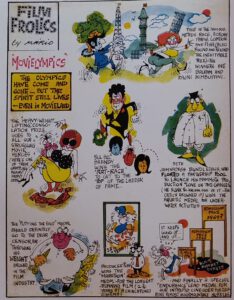

That was the year 1952. Mário had virtually stumbled into the profession of cartooning.[22] To an onlooker the job seemed easy, and everything grist to the mill – from the bureaucracy, fashions, business, and people’s habits, to the animal world, environment, music, society, and even politics – but really, finding humour was no mean task. ‘There are times when you don’t feel funny, or may not feel like laughing, but still have to produce a funny cartoon – like a clown who has got to make people laugh all the time, although he doesn’t feel like laughing.’[23]

Elaborating on his predicament, Mário said, ‘People expect me to come up with jokes and anecdotes to make others laugh. I can’t do that. I enjoy humour if it comes from someone else who knows how to tell a good joke…. I am not a naturally funny person; I may look funny, but I am not funny.’[24] And if a cartoonist’s defining quality it is ‘to detect funniness in people’s behaviour or physical features and draw it, it is equally important to be able to laugh with someone, not at someone, without being cruel,’ said Mário, adding: ‘Humour is something very personal, individual. What’s funny to me may not be funny to you. Sometimes I do something which I think is very funny – and it flops! And people asking you to explain a cartoon flattens it completely.’[25]

Past the initial scramble for work, Mário began to yearn for the blissful spontaneity of his diary sketching. Add to this the fact that political bigwigs were breathing down his neck, and Mário had a sure recipe for disenchantment. Bombay Presidency’s Home Minister Morarji Desai was among the first ones to let his irritation show – something that taught Mário early on that lampooning political animals involved high risk. When he toned down the humour to appease the readers, cartooning quite paradoxically became a ‘serious business’. ‘Cartoonists are very serious people, and cartoons, no laughing matter,’[26] he quipped.

Finally, Mário stopped pursuing individual politicians; he began to see himself as a social caricaturist more than anything else. He is on record as saying, ‘I am not even a cartoonist; I draw… give me a pen and blank paper and I will draw. I just love to draw.’[27]

Acknowledgements: (1) I am indebted to Fátima Miranda Figueiredo for her knowledge and patience translated into many hours of whatsapp chats about her brother Mário and the family; and to Raul and Rishaad de Miranda for their warm welcome and lively conversation. (2) Banner picture: Portrait Atelier Goa (3) Article first published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Lisbon, Series II, No. 12, Sep-Oct 2021

[11] ‘Tale of Two Goans: Mario Miranda & Wendell Rodricks’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5FDLGApfATc&t=5s

[12] Cf. Fernando de Noronha, Momentos do meu passado (Goa: Third Millennium, 2002), p. 146.

[13] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[14] Cf. The Life of Mário (1949, 1950, 1951) ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous), in 2016, 2012 and 2011, respectively. Fátima Miranda Figueiredo reckons that her brother’s diary sketches total up to about 6,750 over a period of 18 years (1934-1951).

[15] He frequented the houses of his relatives, Judge António Miranda and Captain Adolfo Menezes, in Panjim, and Judge Eurico Santana da Silva, in Margão; and often stayed overnight with friends in their hostels.

[16] Nissim Ezekiel, ‘No escape if Mario is looking at you,’ in Mário de Miranda, ed. Gerard da Cunha (Goa: Architecture Autonomous, 2005), p. 276.

[17] As told by Fátima Miranda Figueiredo, 27.5.2021.

[18] Souvenir of the Silver Jubilee of the Loutulenses League (Goa: Imprensa Nacional do Estado da Índia, 1950). Curiously, in the chapter titled ‘The Rising Generation’, Mário figures as an Arts graduate, not as an Artist.

[19] Polly was from Bastorá; other hostelites, Joe Albuquerque and Paulo Miranda, from Loutulim. Cf. Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 14.

[20] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 15.

[21] Femina; Filmfare; The Evening News and The Economic Times.

[22] Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

[23] FTF Mario Miranda, op. cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Manohar Malgonkar, ‘Biography’, in Mário de Miranda, op. cit., p. 24; Conversation with Shri Mario Miranda – 2 (Outtakes), op. cit.

Tribute to my Father

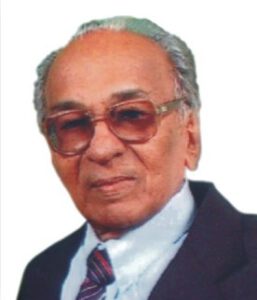

Early this month the social media was abuzz, in anticipation of the twenty-twenties; as for me, I was on a solo trip back to nineteen-twenty. As a child, this year had the earmarks of a happy milestone for me, yet it triggered anxiety for the future. My childhood was a shrine of happy pictures, yet the thought of that golden marker fading into the horizon would fill me with sadness. Why? Because while a young me was looking ahead to what would be, my father Fernando was already looking back upon what had been….

My lone source of anxiety for the future was that I was the eldest child, born in Papa’s forty-fourth year. I knew not how long I would have him: it was a worry I kept to myself so as not to dishearten him. But then, hardly anything disheartened him; he kept pace with his children and even his grandchildren’s progress, and enjoyed the sleep of the just. When he passed on, at 91, he was a grandfather to fifteen. His abiding trust in God was the secret of his longevity – as well as a salutary lesson on the futility of anxiety.

In my naiveté, 1920 still felt charming; as I grew older, I found Papa’s idealism, independence and integrity appealing. I looked up to him, especially because his life hadn’t been easy: the ‘roaring twenties’ of the West had played out quite differently in Portugal and Goa. Following a decade of political turbulence and galloping inflation, the country stabilised and the escudo roared upon the rise of Salazar the economist. Convinced that he was a man with ‘the right intention’, my father held him in esteem for his intellect and honesty – the antithesis of leaders in sham democracies.

After God, it was Goa uppermost in Papa’s mind. The Mass and the Bible alongside spiritual classics were his daily fare. To compensate for arid bureaucratic matters, he put his faith in reading, writing, teaching and music. Even while he took delight in the Romantics Eça, Camilo and Ramalho, he recommended some excellent Goan writers. Until his last breath he lapped up the masters of the Portuguese language, not forgetting two of our very own Goan purists, Costa Álvares and Filinto C. Dias.

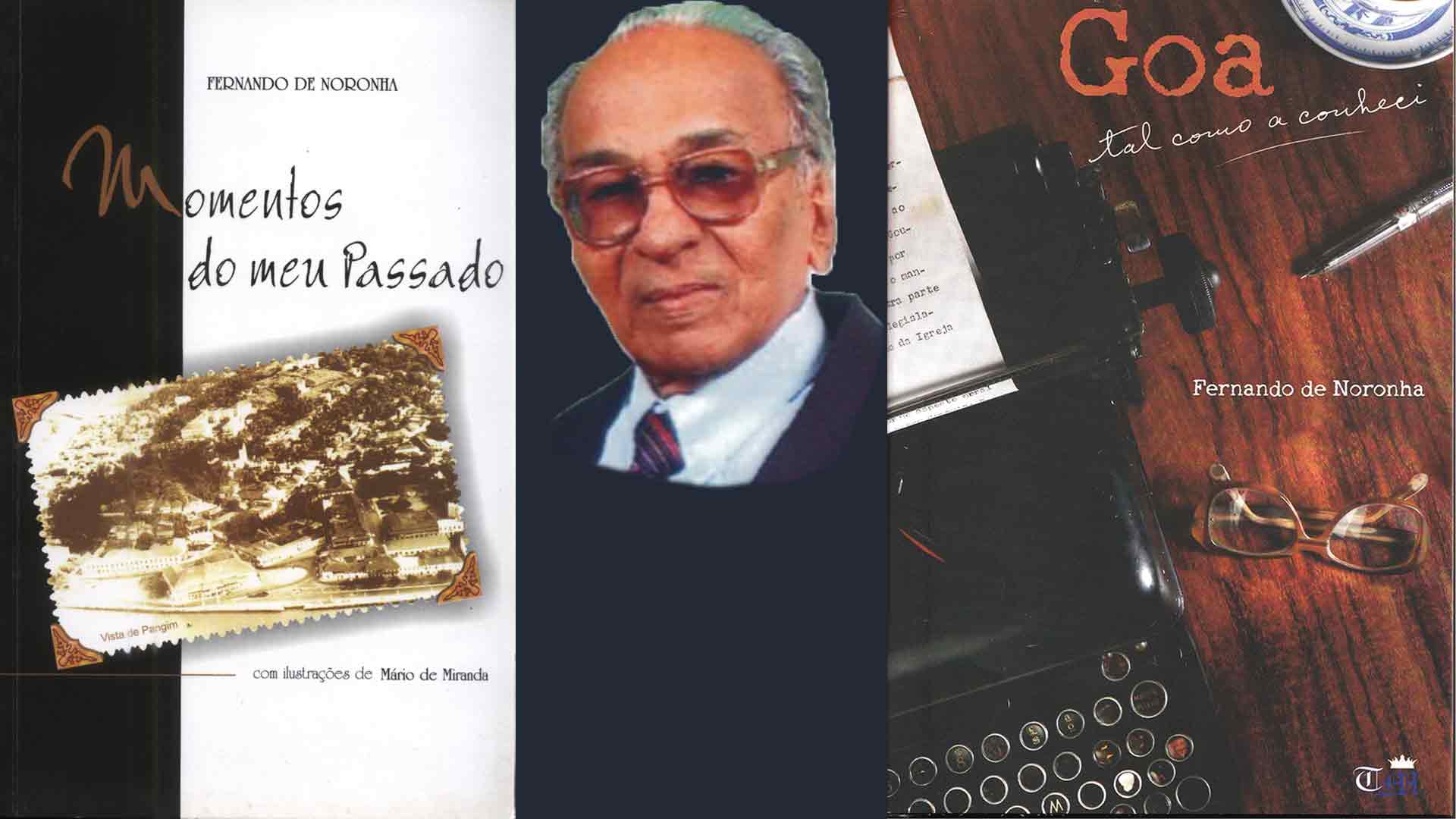

One gets a bird’s eye view of Papa’s outlook from his first book, Momentos do meu Passado (Moments from my Past). Much of it is what he used to recount animatedly at the dinner table or talk over with relatives and friends. He obliged us by writing this slim volume comprising ‘figures, facts and facetiae’: pen sketches of over thirty personalities from the Goan social and political milieu; some little-known facts of contemporary history; and a host of anecdotes dating back to his Lyceum days. In his words, he wished ‘to quench saudades of a not so distant past, when one lived in a happy and carefree manner unique to Goa.’

It took me some time to appreciate Papa’s simple and straightforward nature. And noticing how people would often agree but also end up severing ties with him, I learnt that truth can indeed puzzle, confound, hurt… Papa’s intermittent observations on public affairs are lost in the thicket of Heraldo and A Vida for, whilst a bureaucrat in two key departments during the Portuguese regime, he used pen names of which he kept no record. In 1967, his commitment to ferry people to the booths on the occasion of the Opinion Poll (16 January, his birthday and feast of St Joseph Vaz) fetched him a resounding office memo.

It warms the cockles of our hearts to see that Papa’s second book, Goa tal como a conheci (Goa as I knew it), contains the essence of his views on people, events and ideas. Covering as he did twentieth-century Goa’s political and administrative affairs, society, culture, and religion, in a total of eighteen chapters, this offering is a testimony of love for the land and the people. It is also a tribute to the Portuguese language that was so dear to him. After opting to retire from public service, he taught that idiom at a city college and co-founded a weekly, A Voz de Goa. At Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church he prayed in that ‘language of the angels’ and put together a choir at Sunday mass.

Music was high up on his agenda ever since his father purchased a gramophone and a maternal uncle and self-taught violin virtuoso played along. An attractive feature of Papa’s day was his whistling and playing of the harmonica, providing the household with a kind of crash course in classical and semi-classical music. The mandó moved him very especially (he ensured that it featured at his children’s wedding parties) and so did two popular Konkani films of his time which, he said, ‘foster Goan patriotic feelings’. The Goan reality, however, was a far cry from what he had envisioned, so I can say with Wodehouse that ‘if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.’

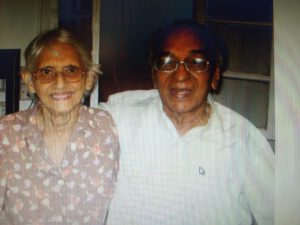

No tribute to our father would be complete without a reference to our dearest mother Judite da Veiga, who was the love of his life, the reason of his being. On his death bed I heard him thank her for half a century of togetherness. She, their five boys and families, was all that he ever wanted. We have lost him in body, not in spirit. He has become greater in death, our strength and consolation, our conviction that there can be no anxiety for the future….

Herald, 19.01.2020, published an abridged version

For this full version see Revista da Casa de Goa (Lisbon), March-April 2020

https://issuu.com/casadegoa/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n3_-_mar-abr_2