Love in Verse

VISIONS FROM GRYMES HILL, by António Gomes. Turn of River Press, 1994, 95 pp. Rs. 100

António Gomes, a eleven-year Goan veteran of Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, is presently metamorphosed into a poet-philosopher. He examines the chemistry of suffering and joy, and attempts to decipher the mystery of life and death. After his wife died of cancer, in 1989, he thought he would never write poetry again. His inner world had been shattered by her departure. But God and Time are better healers than all our earthly physicians put together, and Gomes gradually came to terms with his loss and became whole again.

Visions from Grymes Hill is divided into two sections: “The Twilight Landscape” and “Poet’s Den”. In the first, the poems are more personal, reflecting his intense pain on the death of Marina. Gomes feels helpless that as a doctor he could not save her life. As he confesses in the Preface, “a doctor, a scientist and a heart specialist, I was engrossed in the miracles of Science. Yes, indeed! Science for me then was the one god I knew and understood above all gods. I was angry at this god for abandoning me. This god through whose intercession I had often mended the hearts of many men and women.”

Death laid its icy hands of her like an untimely frost upon the sweetest flower on all the field. The poet, unable to save her, is now in search of her. The poem “Visions” is a series of dreams reflecting this search, if not to find her – to find the answer. Born into a Roman Catholic family from Loutulim, Gomes now presents himself as an eclectic philosopher travelling through Hindu and Buddhist mythologies to find “the noble truth of the cessation of suffering” through “renunciation”.

The sad and humdrum life of a lonely man is reflected in the tone of some of the verse; but the sombre atmosphere turns to light whenever the poet chances upon the understanding of the mystery of life. Then he transcends his troubles and marvels at the myriad colours of human nature. His magnanimous heart looks upon the suffering of the “beggar and the hungry child”; his singing soul revels in music and dance as he draws the fine “portrait of a jazz pianist”, and Stan Getz.

Despite the magical confusion of his inner world, Gomes does spare a thought for Tiananmen Square and the Berlin Wall, communist dictatorships and Mikhail Gorbachev. All this is woven into his sensibility but he compulsively returns to “the image of my dear sick wife/Falling, rising, struggling/ Beautiful and hopeful to the very end”. Beautiful and hopeful, which is why even while a window closes on him with loss and sorrow another opens up with joy and hope. And as he turns his back on the images of the fateful year of 1989 “I welcome 1990, dancing with Tania, my only child”.

The “Poet’s Den” is an epic poem in which we follow the poet’s journey to disparate worlds and cultures. On seeking inspiration from the muse to write an epic, the poet is taken to a den where he encounters dead poets, ancient and modern. We are thus privileged to listen in on his intimate and far-reaching conversations with the great Bards from Dante, Goethe, Rilke, and Camões to Whitman, Tagore and Neruda.

The thematic range of this Section goes from the personal and religious to the social, economic and political. The issues reflect the events of the late 1980’s and early 90’s, “new challenges that have the immense potential of changing our world and our civilization”. Curiously, in these poems, written in the form of dialogues, Gomes blends his own poetry with that of the bards he encounters.

In Visions from Grymes Hill, which is his residence at Mount Sinai, António Gomes comes out as a man with the heart of a physician and the soul of a poet. Most touching is his line in the Preface: “I hope that those who read this book or parts of it will find these poets healing”. Witness the selflessness, the devotion, and the magnanimity of a fine doctor and sincere husband who invites us to partake of the pathos and passion of being fully human. The reader cannot help wishing that the poems have been cathartic for the writer himself.

(Herald -The Illustrated Review, 1-15 Sep 1995)

Mapping Goa's Architecture

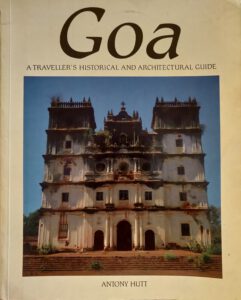

Goa - A Traveller's Historical and Architectural Guide, by Antony Hutt. Scorpion Publishing Ltd, England. Rs 200

It could well be called a serious work written for the casual traveller. More specific academic exercises have preceded this one since the 1950s but the highlight of Antony Hutt's book is his comprehensive treatment of Hindu, Christian and Muslim architecture – civil, religious and military.

Out of the nine chapters the first five are devoted to the history of Goa – right from the early times down through the Hindu and the hitherto neglected Muslim period, up to the Portuguese connection, when Goa got to partake directly of the history of the modern world. However, the 20th century is almost entirely left out.

The historical account is highly readable, largely chronological, though desultory at times. Refreshing it is to find the history of tiny Goa placed in the larger context of the history of India and the world. Hutt is well disposed towards the Portuguese, the Inquisition notwithstanding, and is of the opinion that they "inaugurated the most brilliant period in her history".

Old Goa alone becomes the subject of chapter 6. The Indian Baroque church of the Holy Spirit (St Francis of Assisi), the church of Our Lady of the Rosary, St Catherine, the Cathedral See, Grace Church (St Augustine's), the Royal Chapel (St Anthony), St Monica Nunnery, the convent of St John of God, the Minor Basilica of Good Jesus, St Cajetan, church of Our Lady of the Mount, the Viceroys Arch, and the Archaeological Museum – twelve monuments, all of them mapped. Good treatment this but no real revelations whatsoever.

The next few pages are devoted to Portuguese architecture outside the capital city. This is followed by a novel chapter on the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture.

It is in the following chapter that the author is least original in what concerns civil and religious architecture. Salcete, and more in particular, Loutulim, forms the main thrust, and what follows is a routine description of only the better known houses in Salcete – the da Silva mansion in Margão, the Miranda and Figueiredo houses in Loutulim and the Menezes Bragança in Chandor, the only exceptions this time being the Salvador Costa house in Loutulim and perhaps also the Souza Gonçalves and Albuquerque mansions in Bardez.

On the other hand, a novelty is certainly the description of the forts of Goa: Tiracol, Chapora, Aguada, Reis Magos, Gaspar Dias, Cabo, Marmagoa, Cabo de Rama and the inland fort of Santo Estevam, all find their rightful place in Hutt's book.

In contrast with the earlier chapter, what constitutes a real contribution is Hutt's elaboration of the Hindu contribution to Goan architecture. It is, however, most unfortunate that there is not a single picture of any of the six Hindu houses described – the Sinai Kundaikars in Kundai, the Ranes in Sanquelim, the Khandeparkar house in Khandepar, the Dempo and Mhamai Kamat houses in Panjim and the Deshprabhu palace in Pernem. We are only left to imagine what they really look like.

More than nine temples are included, the earliest being the rock-cut sanctuaries of the 3rd-6th centuries A.D., most of which are Buddhist in origin; Sri Mahadeva temple, Tambdi-Surla; Shiva temple (Curdi), Saptakoteshwar (Naroa); Mahalsa, Mangueshi, Shantadurga; Kamakshi (Siroda), and Mahalaxmi (Bandora). There are specific references to the "odyssey" of many Hindu deities of Goa.

Hutt was in love with Goa and visited it often from the 1970s to the 80s. He could not then possibly miss out a comment on the life of the Goan people. And the final chapter is just that, a paen to the Goan genius: the warmth and colour of the people, the traditional communal harmony, and so on. But this sociological exercise should have been accompanied by a more definite statement on the nature of popular architecture in Goa – a point that is sacrificed at the altar of elite architecture, so to say.

A good bibliography can serve as a delicious dessert for the curious mind. Sad to say, here the book is a complete let-down. The scanty information cannot satisfy even the least curious of travellers/readers. There is not even a minor reference to the works of Mário Tavares Chicó or Carlos de Azevedo from Portugal nor to the historical works of Danvers, Gabriel de Saldanha or José Nicolau da Fonseca. Rather mysterious references are made to books published after the author's death, and for that matter, other books figure in the bibliography from which not a line or illustration is traceable in the text. Also missing is a detailed map of Goa.

All in all, an impressive book. Good get-up, fine printing. For certain shortcomings of the text, every reader would be willing to make certain concessions given the author's premature death in 1985.

(Goa Today, November 1989)