Konkani before and after Dalgado

In 1917, Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, an internationally renowned Goan linguist, forever changed the course of the Konkani-Marathi controversy. In a nine-part series titled “O concani não é dialecto do marata” (‘Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi’), published in the Panjim daily Heraldo, he analysed the linguistic and grammatical characteristics of Konkani, demonstrating its identity as distinct from that of Marathi. But, then, what events led Mgr. Dalgado to write the series?

Fabricated controversy

The Konkani-Marathi controversy is not as ancient as it might seem; it is a nineteenth-century fabrication. Konkani, which, like Marathi, evolved from Prakrit, began to make rapid strides in the linguistic, lexicographic, and literary fields, thanks to the ingenuity of European missionaries in sixteenth-century Goa. It is another matter that their interest began to wane, and indifference turned into state hostility, to some extent, at least on paper. This brought the first modern literary period of Konkani literature to an inglorious end.

In the eighteenth century, literary production in Goa was conspicuous by its absence, due to the shutdown of the printing press. As a result, not only did Konkani get relegated to the background, but Goa itself became a backwater. Even so, there was not a doubt about Konkani’s linguistic status until the year 1807, when John Leyden dubbed it a dialect of Marathi. His ideas began to gain currency in British India. When those echoes reached Portuguese India, Konkani was excluded from the curriculum of the first state-owned schools set up in 1831. By now, in the new Liberal regime, it suited Goan Catholic elite to adopt Portuguese as their cultural language, while the Hindu elite continued to seek refuge in Marathi and turned to Portuguese in the following century.

Meanwhile, in 1858, J. H. da Cunha Rivara’s famous essay on the Konkani language (Ensaio histórico da língua concani) decried Goa’s contempt of its native language and defended its dignity. His realisation was perhaps a byproduct of a new Orientalist consciousness, which prized the rediscovery of indigenous languages. But alas, it is Marathi and not Konkani that drew the benefit. In 1869, at the behest of Goa’s official translator Suriagy Ananda Rao, the state government banned the use of Konkani, while Marathi ruled the roost at the Panjim Lyceum.

A decade later, when R. G. Bhandarkar in Bombay reiterated Konkani’s dialect status (cf. Wilson Philological Lectures, 1877, a series of seven lectures on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages), scholars favouring the dialect theory slightly outnumbered those favouring the language theory. But a fitting reply awaited Bhandarkar in 1881, when José Gerson da Cunha systematised and coordinated the arguments of the language theory in his Konkani Language and Literature. Nonetheless, in 1905, the Linguistic Survey of India, published by the British Government, buttressed the dialect myth.

Divided Goa

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

While the Konkani movement was thus gaining momentum within the community in Bombay, back in Goa, Thomaz de Aquino Mourão Garcez Palha and Fernando Leal, two mestiços (persons of mixed blood, Portuguese and Goan), who had probably caught the Orientalist bug, began a crusade for the “resurrection of Konkani”. They were supported mostly by members of the Goan Catholic elite.

As regards the Hindu elite, in 1916, when the ayurvedic physician Dada Vaidya (Ramachondra Panduronga Vaidya) spoke in Konkani at Goa’s first Provincial Congress, Marathi writer Xamba Suriarao Sardesai shouted him down and followed it up with a two-part article disparaging the Konkani movement. The division of Goan society was complete, not only between educated Christians and Hindus, but also within the Hindu community.

By February 1917, therefore, the stage was set for Dalgado’s intervention from distant Lisbon. The tireless Goan Catholic missionary was now on a mission to prove Konkani’s credentials as a language. He had published a Konkani-Portuguese dictionary in Bombay (1893), and a Portuguese-Konkani dictionary in Lisbon (1905), both of which used the Devanagari and Roman scripts. The university professor and Fellow of the Portuguese Academy of Sciences was an authority on the influence of Portuguese on Asian languages, and his thoughts kept returning to Konkani. Significantly, his last unpublished work was a Konkani Grammar, which Fr Mousinho de Ataíde translated into English in Dalgado’s death centenary year, 2022.

Decisive entry

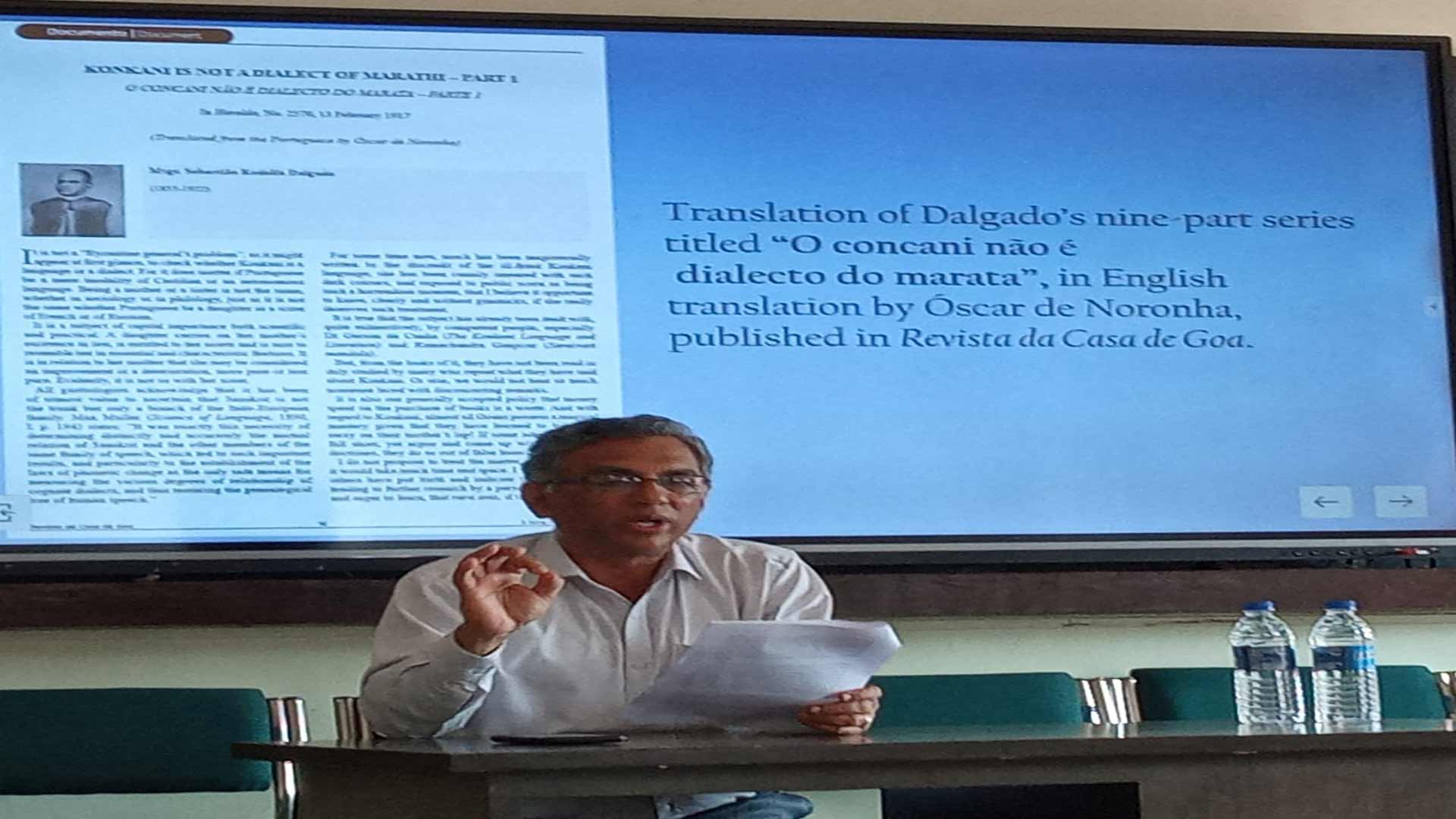

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s entry was decisive. It was a watershed moment in the history of Konkani Studies. Portuguese-language newspapers in Goa as well as bilingual papers in Bombay began to comment on Dalgado’s efforts in the field. After him, Jules Bloch showed how distinct Marathi was from Konkani; S. M. Katre paralleled Bloch’s book by writing The Formation of Konkani, and together with V. P. Chavan, helped further Konkani’s position as a separate language.

Varde Valaulikar’s writings continued Dalgado’s work of demonstrating Konkani’s individuality. Curiously, Shenoi Goembab began by writing in Marathi, and after switching to Konkani, first wrote in the Roman script. Seven of his twenty-nine books are in the Roman script. In fact, there was no Konkani worth the name in the Devanagari script in Bombay, and much less in Goa.

Perhaps Dalgado and Valaulikar never met or exchanged correspondence, but they shared the same vision. Valaulikar, who knew Portuguese, must have read Dalgado’s rejoinder to Xamba Sardesai. While Valaulikar carried out a literary crusade in Bombay, Dalgado’s academic legacy was kept alive by his pupil Mariano Saldanha in Lisbon. Dalgado died in 1922, and Shenoi Goembab in 1946. In 1952, Mariano Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth All-India Konkani Porixod held there. As a votary of the Roman script, Saldanha’s address was printed in the Roman script.

By the 1950s, the demand for linguistic states had gained significant momentum, leading to the creation of the Telugu-speaking Andhra out of the State of Madras. Much earlier, the Indian National Congress had organised its provincial committees along linguistic zones, signalling an early form of the concept. Dalgado and Valaulikar’s vision of Konkani in the Devanagari script dovetailed into that concept, whereas Saldanha envisioned the Roman script for Konkani in Goa. It did not materialise in the post-1961 scenario, for obvious reasons.

Goa post-1961

It was an entirely new ballgame after Goa got into the Indian Union. Maharashtra had laid claim to Goa, deeming Konkani a dialect of Marathi. The Goan elite, which was once divided between Portuguese and Marathi, leaving Konkani to fend for herself, now realised that only Konkani could help preserve their identity. It was a David and Goliath situation, in which Konkani won because the language was on the people’s lips and nobody could take it away. Its literature was perhaps not on a par with best in the country, but it had a strong foundation built by Dalgado and Valaulikar.

Hence, while Valaulikar is regarded as the Father of Modern Konkani Literature, Father Dalgado, by his fundamental contribution to the development of the language, ought to be regarded as the Grand Father (pun intended) of Modern Konkani. Their impact was felt at the time of the Opinion Poll and when Sahitya Akademi recognised Konkani as a literary language; when Goa achieved statehood and Konkani became the state language, and when Konkani was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

Thereafter, Konkani came into a privileged position, as never before. It would seem like a time to consolidate had arrived. For instance, in the Konkani world beyond Goa, it would pay dividends to make the most of the multi-script situation; but that was not to be. In Goa, the issue of script remains Konkani’s Achilles heel. The sooner this is resolved the better, to ensure the interests of all the user communities; their wellbeing is bound to produce positive results for the popularity and expansion of the language. The more the scripts the better.

Case for the Roman script

It is also a time for some reflection. Has the shared legacy created by Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab been put to creative use? It would be interesting to consider what their response would be to our globalised world. How would they respond to demands for recognition of the Roman script in today’s multilingual and multicultural world? Would they consider it an opportunity to woo back Konkani speakers at home and in the diaspora, and to win new speakers from across the big wide world? Would they appreciate the possibility of Konkani finally becoming at once a means of communication and identity marker?

After all, living languages are dynamic, and no script is perfect. Goykanadi was the earliest known native script that Konkani used, before it was supplanted by others. Similarly, the earliest known script for the English language was the Anglo-Saxon futhorc. From the seventh century onwards, the Latin alphabet began to replace the futhorc, though they coexisted for a time in England.

It is the same in India. The Latin or Roman script is not to be considered foreign; it is as Indian as the English language in the country. If the English language can be made official, so can the Roman script, or any other for that matter, if numbers and the volume of work justify it.

Not to let script remain a divisive issue, would Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab, then, consider letting Goa be the first state in the Indian Union to successfully resolve a multi-script situation? Any script that has worked in the past ought to work in the future. This applies to the Roman script as well. Surely, Dalgado’s mission was to save the language over and above the script.