Vaz, Montfort and their self-consecrations

Marian dedication stands enriched by the singular contributions made by Joseph Vaz (Goa, 1651 – Sri Lanka, 1711) and Louis de Montfort (France, 1673 – France, 1716).

Vazian Formula

Joseph Vaz expressed his profound love and tender care to the sublime Queen of the Universe and Mother of Fair Love in a memorable document known as the “Deed of Bondage”,[1] which reads as follows:

Be it known to all who see this deed of bondage, the angels, men, and all creatures, that I, Father Joseph Vaz, sell and offer myself as a perpetual slave of the Virgin Mother of God, through a free, spontaneous and perfect gift that in law is said to be irrevocable inter vivos; I give myself and my assets that she, as my true Lady, may dispose of me and of them according to her will; and as I consider myself unworthy of such an honour, I beseech my Guardian Angel and the glorious Patriarch St Joseph, most beloved Spouse of this Sovereign Lady and saint of my name, and other citizens of heaven, to ensure that she includes me in the number of Her slaves. In witness thereof I seal this with my name, and would have liked to seal it with the blood of my heart. Written at the Church of Sancoale, at the foot of the altar of the same Virgin Mary Mother of God, Our Lady of Health, this fifth day of August, Feast of Our Lady of the Snows, one thousand six hundred and seventy-seven. – Joseph Vaz.[2]

In Goa, the consecration has been traditionally looked at as something peculiar to St Joseph Vaz. The original “Deed” is not traceable, but Joseph Vaz’s first published biographer, the Oratorian priest Sebastião do Rego (1699-?), vouches that he read and kissed it several times, in the hope that he would be touched by a spark of the great fire with which it was written.[3] Did the Saint leave the manuscript behind with the Congregation, or with his family, in Goa? Might he have carried it with him to Sri Lanka? Hopefully, it will one day be found among the Oratorian documents.

What might have inspired Joseph Vaz to commit himself thus to our Divine Mother? Was it the influence of a teacher, from among the Jesuits, or more likely from among the Dominicans, who are known to have been great Marian devotees? Did Joseph find motivation in the books of spirituality that he came across in the rich seminary libraries? Further, why did he take the Feast of Our Lady of the Snows for a red-letter day in his life? Was it the fact that she is the patroness of Rome’s most important Marian church popularly called Santa Maria Maggiore?

While answers to those questions may remain conjectural, one thing is sure: what the Apostle of Sri Lanka has bequeathed to humankind is a precious document with a tenor both mystical and direct; it is “a unique deed inter vivos, in which Fr. Joseph Vaz is at once the donor and donation, notary and clerk; and the Blessed Virgin, donee and witness, while the Patriarch St Joseph, Spouse of the Donee and his namesake, his guardian angel and the other citizens of heaven are constituted intercessors before the Donee”.[4] Joseph Vaz is ready, Christ-like, to shed blood in atonement. And far from alienating the reader, the legalese underscores the solemnity of the act.

Montfortian Formula

Coming to Montfort’s act of consecration: it is the grand finale to his Treatise on the True Devotion to the Blessed Virgin.[5] His formula, thrice as long as Vaz’s, reads as follows:

O Eternal and Incarnate Wisdom! O sweetest and most adorable Jesus! True God and true man, only Son of the Eternal Father, and of Mary, always virgin! I adore Thee profoundly in the bosom and splendours of Thy Father during eternity; and I adore Thee also in the virginal bosom of Mary, Thy most worthy Mother, in the time of Thine incarnation.

I give Thee thanks for that Thou hast annihilated Thyself, taking the form of a slave in order to rescue me from the cruel slavery of the devil. I praise and glorify Thee for that Thou hast been pleased to submit Thyself to Mary, Thy holy Mother, in all things, in order to make me Thy faithful slave through her. But, alas! Ungrateful and faithless as I have been, I have not kept the promises which I made so solemnly to Thee in my Baptism; I have not fulfilled my obligations; I do not deserve to be called Thy child, nor yet Thy slave; and as there is nothing in me which does not merit Thine anger and Thy repulse, I dare not come by myself before Thy most holy and august Majesty. It is on this account that I have recourse to the intercession of Thy most holy Mother, whom Thou hast given me for a mediatrix with Thee. It is through her that I hope to obtain of Thee contrition, the pardon of my sins, and the acquisition and preservation of wisdom.

Hail, then, O immaculate Mary, living tabernacle of the Divinity, where the Eternal Wisdom willed to be hidden and to be adored by angels and by men! Hail, O Queen of Heaven and earth, to whose empire everything is subject which is under God. Hail, O sure refuge of sinners, whose mercy fails no one. Hear the desires which I have of the Divine Wisdom; and for that end receive the vows and offerings which in my lowliness I present to thee.

I, N_____, a faithless sinner, renew and ratify today in thy hands the vows of my Baptism; I renounce forever Satan, his pomps and works; and I give myself entirely to Jesus Christ, the Incarnate Wisdom, to carry my cross after Him all the days of my life, and to be more faithful to Him than I have ever been before. In the presence of all the heavenly court I choose thee this day for my Mother and Mistress. I deliver and consecrate to thee, as thy slave, my body and soul, my goods, both interior and exterior, and even the value of all my good actions, past, present and future; leaving to thee the entire and full right of disposing of me, and all that belongs to me, without exception, according to thy good pleasure, for the greater glory of God in time and in eternity.

Receive, O benignant Virgin, this little offering of my slavery, in honour of, and in union with, that subjection which the Eternal Wisdom deigned to have to thy maternity; in homage to the power which both of you have over this poor sinner, and in thanksgiving for the privileges with which the Holy Trinity has favoured thee. I declare that I wish henceforth, as thy true slave, to seek thy honour and to obey thee in all things.

O admirable Mother, present me to thy dear Son as His eternal slave, so that as He has redeemed me by thee, by thee He may receive me! O Mother of mercy, grant me the grace to obtain the true Wisdom of God; and for that end receive me among those whom thou lovest and teachest, whom thou leadest, nourishest and protectest as thy children and thy slaves.

O faithful Virgin, make me in all things so perfect a disciple, imitator and slave of the Incarnate Wisdom, Jesus Christ thy Son, that I may attain, by thine intercession and by thine example, to the fullness of His age on earth and of His glory in Heaven. Amen.

Montfort’s formula begins with an invocation of the Incarnate God. The Christological opening is quickly followed by Marian veneration, in acknowledgment of the Incarnation. Our Lord’s death on the Cross is an act of incomparable nobility, yearning as He did to rescue humanity through His sacrifice; our inspired author stresses that He emptied himself, taking the form of a slave (Phil. 2:7). A self-imposed slavery like this can only be termed a slavery of love.

Montfort points to a divine enslavement that is liberating, as opposed to human liberty that can be enslaving. And what can be better than following Jesus’ example of submitting Himself to His holy Mother? At the heart of the Montfortian formula is the recognition of human unworthiness to stand in the presence of our Lord and God, other than through His Mother’s intercession. The point of resolution comes with the renewal of the baptismal vows; an express renunciation of Satan; and decision to follow Jesus and be faithful to Him.

Appraisal

The two consecration formulas are essentially the same: note the similarity of the terms employed. In addition, Vaz sells himself as a slave while offering himself as a “gift in perpetuity”; he humbly calls upon the angels, men and creatures, to mediate, for is it not perfectly justified to take one’s Guardian Angel into confidence; to appeal to the saint of one’s name; and, as per the communion of saints, invoke their intercession before her.

Vaz’s act is crisp and intimate; Montfort’s, uninhibited and elaborate. St Joseph Vaz’s singular self-offering happened when he was 26 years of age; it is not known when St Louis de Montfort made his, but he included a very brief formula of consecration at the end of his Love of Eternal Wisdom (c. 1703), when he was 30. Vaz embraced the spirituality of St Philip Neri eight years after his consecration; Montfort became a Dominican tertiary in 1710, three years before his Treatise.

Finally, Fr. Joseph Vaz is not known to have ever spoken publicly about his “Deed”, so it may be regarded as a very personal statement. It was for sure a product of his deep conviction; none before him are known to have embraced the slavery of love in Goa,[6] and none from among his confreres are known to have followed his example. On the other hand, not only is Montfort’s Treatise highly elucidative, his consecration formula is an expansive public declaration of what every Catholic ought to strive for; it is a standing invitation to build a profound and intimate union with Christ through Mary.

(Excerpted from my article titled “Two Saints and a Consecration for our Times”, in St Joseph Vaz for All Times, edited by Fr. Aleixo Menezes and published by the Archdiocese of Goa and Daman, 2015, and posted here with minor alterations)

[1] This is sometimes referred to as a “Letter”, in a literal translation of the Portuguese “Carta do Cativeiro”. Whereas “Cativeiro” could be variably translated as captivity, bondage, or slavery; “Carta” would be better translated as “Deed”, and not simply as “Letter”, particularly considering the legal language in which it is couched.

[2] Translated by this author. Cf. Óscar DE NORONHA, Of Divine Bondage: The Epic Life of St Joseph Vaz, (Third Millennium: Panjim, 2014), 25

[3] Sebastião DO REGO, Vida do Venerável Padre José Vaz (Imprensa Nacional: Goa, 19623), 172.

[4] Seráfico MISQUITA, Ven. Padre José Vaz, Apóstolo de Ceilão (Tipografia Rangel: Goa, 1969), 30.

[5] St Louis DE MONTFORT, True Devotion to Mary. Transl. Frederick William Faber. Revised edition. (Montfort Publications: New York, 1967), 227-229.

[6] St Louis de Montfort himself has said that although the true devotion is an easy way, few saints have entered upon it. Cf. James Patrick GAFFNEY, ed., Jesus Living in Mary, op. cit., 231.

What was the Inquisition? - 2

Considering that the secular mind is quick to make the very word ‘Inquisition’ look odious, is it not its bounden duty to also check its own moral standards? Can our generation be sure that future generations will not be as uncharitable towards us as we have been vis-à-vis the Inquisition?

It is only fair that an institution or an event be looked at in the light of its age. Hence, before we draw up a balance sheet of the Inquisition, let’s look at some of its features. When the medieval institution was eventually replicated in many countries, there were inevitable changes in its set-up from place to place; however, its nature and procedures remained essentially the same, as outlined below.

Features of the tribunal

a) Nature: Ecclesiastical courts dealt regularly with disputes concerning discipline, administration of the church, and spiritual matters. But in places where heretics were strongly entrenched, the Church set up the inquisition as a special court with permanent judges or inquisitors. It was a formal court with rules of canonical procedure; its judges executed doctrinal functions in the name of the Pope. Thus, the Congregation of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition, or Holy Office, established in Rome in 1542 was historically continuous with the episcopal courts of earlier times and with the ones set up later. In the age of liberalism the powers of the tribunal came to be limited by local control and resistance.

At establishment of the inquisition in the thirteenth century, members of the Dominican and Franciscan Religious Orders, newly set up then, were offered the inquisitorial task, in view of their superior theological training. There is no reason to believe that those judges were in any way intellectually and morally inferior to their counterparts in modern judicial tribunals. Some inquisitors were no doubt harsh; but their lot has to be judged as a whole. Some errant inquisitors were even deposed and then incarcerated for life.

b) Procedure: Any new inquisition tribunal began by declaring a “period of grace” for the local Catholics. When summoned before the inquisitor, those who confessed their faults of their own accord were given a mild penance. When suspects did not report, and meanwhile much evidence had been obtained against them through the parish priest or lay persons, such suspects were cited before the judges and the trial began. If they made a clean breast of their faults, the affair was soon concluded to the advantage of the accused. If they entered denial even after swearing on the Gospels, the evidence already collected was put forward.

It is not known for sure whether the accused were imprisoned throughout the period of judicial inquiry. It seems quite unlikely that they would be, considering the burden on the exchequer. Nor was it even necessary, for freedom of movement was conditional: the suspect had to promise under oath to be available for inquiry and to accept the inquisitor’s sentence with good grace. Obviously, the judge would be favourably inclined if the suspect kept the oath. Besides, the inquisitor could grant bail or have reliable bondsmen to stand surety.

Medieval courts used torture as means of eliciting the truth. The inquisition adopted the method a few decades after its inception – and it is still part of judicial inquiry in many countries. However, torture was permitted only after all other expedients (counselling, coaxing, instilling fear of death, and even confinement) had been exhausted, or if the accused was inexact in his statements and virtually convicted by manifold and weighty proofs.

Torture was to be applied only at any one stage of the inquiry and without causing loss of life or limb. Many a judge skipped this procedure, considering it deceptive and ineffectual, but there were others who depended on it and even exceeded their authority. This made the inquisitor and other officials liable for suspension. Sometimes pressure was exerted in this regard by the civil authorities, overshadowing the ecclesiastical purposes of the inquisition.

While it was mandatory to have depositions by at least two witnesses, some judges would demand more. The Church initially believed that testimony of an "infamous" person was worthless before the courts, but later began to accept their evidence at nearly full value in trials concerning the Faith. Similarly, while at first it was a rule to withhold the names of the witnesses from the accused person, by and by naming witnesses was mandatory, but no personal confrontation of witnesses or any cross-examination ever allowed. Needless to say, false witnesses were severely punished.

It is a pity that witnesses hesitated to appear for the defence, fearing that they would be suspected of heresy. Similarly, the defendant rarely secured legal advisers, so those accused were obliged to respond personally to the main points of a charge. If thrown behind bars, they were given pen and paper for the purpose but no books to read or refer to. Years later, the law provided for heretics to be granted a legal adviser who was beyond suspicion – upright, skilled in civil and canon law, and zealous for the faith.

The accused could let the judge know his enemies; and should these turn out to be the accusers in the case, the charges would be quashed.

c) Bishop and the councils: These were introduced as a system of checks and balances, to save the inquisition tribunals from arbitrariness and caprice. The accused were also referred to the bishop who together with the inquisitor and a number of boni viri – upright and experienced men well versed in theology and canon law – would be summoned for the purpose of deciding on two questions: whether guilt lay at hand and what punishment was to be inflicted.

To preclude personal considerations, cases would be submitted to the council without naming any names. The role of the good men was advisory in nature, yet the final ruling was usually in accordance with their views.

The inquisitors were also assisted by a consilium permanens, or standing council, composed of other sworn judges.

d) Revision: When a decision was revised, it was in the direction of clemency.

e) Imprisonment: If the prison conditions were not up to the mark, the local bishop was supposed to look into the matter. If necessary, he would have meals provided to the prisoner from the proceeds of the confiscated property belonging to the latter.

f) Right to Appeal: The accused could reject a judge if he sensed some prejudice and, at any stage of the trial, appeal to a higher tribunal in the country’s capital or in Rome. The documents of the case would be dispatched there under seal. People would not do so as a matter of course, considering the time and money that it entailed; but sometimes it was considered worth the effort.

g) Punishment: One or two days prior to the formal pronouncement of the verdict,the charges were read out to the respective persons again and in the vernacular. Then they would be told where and when to appear to hear the verdict.

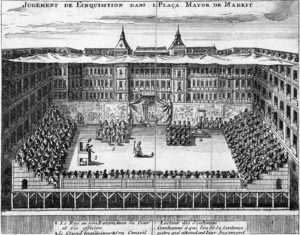

The final decision was usually pronounced with solemn ceremonial at the sermo generalis (a short discourse or exhortation), which later came to be known as auto-da-fé (act of faith). This was not a regular affair; it was held biennially or triennially, or even more rarely.

The auto-da-fé ceremony began very early in the morning. It comprised Mass, prayer, a public procession of those found guilty, and a reading of their sentences. It was followed by the investiture of the secular officials, who were made to vow obedience to the inquisitor in all things pertaining to the suppression of heresy. The so-called "decrees of mercy" (commutations, mitigations, and remission of previously imposed penalties) were followed by a fresh listing of offences and due punishments assigned to the guilty.

The listing went on from the minor to the major punishments, all of them as per the law in force. Some punishments were simply penitential in nature: building or visiting a church, going on pilgrimage more or less distant, offering a candle or a chalice, and the like. Minor punishments also included fines; road-making; whipping; the pillory, and so on. Major punishments comprised imprisonment in various degrees; confiscation of property; excommunication and the consequent surrender of the accused to the civil power for life imprisonment or death at the stake.

The auto-da-fé brought the inquisitional proceedings to an end.

h) Victims

For some, the word ‘Inquisition’ conjures up dreadful images of people arbitrarily sent to the stake. But the facts don’t bear out those fears. What those unscrupulous critics have done down the centuries is point out a few high-profile cases of clerics, scientists, and even saints (St Joan of Arc, Galileo Galilei, Edgardo Mortara, Giordano Bruno, among others) and then generalise about the inquisition. And about these heavy-weights, they hardly ever qualify their remarks.

Punishments in perspective

The indisputable fact is that, due to partial unavailability of records, many finer details are not known for sure. For instance, the number of those who died at the stake cannot be determined even with approximate accuracy. No serious historian, however, has ever stated that the figure is unconscionably high, for available data bears out the contrary. In fact, the numbers seem very low compared with the high-sounding rhetoric surrounding the tribunal.

Beginning from the nineteenth century, historians gradually compiled statistics drawn from the surviving court records. For instance, according to information available on Wikipedia, Inquisition historians Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras studied the records of the Spanish Inquisition, which list 44,674 cases of which 826 resulted in executions in person and 778 in effigy (a straw dummy was burned in place of the person). Professor William Monter estimated there were 1000 executions between the years 1530–1630 and 250 between the years 1630–1730. Spain specialist Jean-Pierre Dedieu studied the records of the Toledo tribunal, which put 12,000 people on trial. For the period prior to 1530, British historian Henry Kamen estimated there were about 2,000 executions in all of Spain's tribunals. Italian Renaissance history professor and Inquisition expert Carlo Ginzburg had his doubts about using statistics to reach a judgment about the period given that in many cases the evidence has been lost.

The same holds true for Goa, where the first tribunal outside Europe was established in the year 1560 and functioned intermittently up to 1812. According to history professor José Pedro Paiva of Coimbra, there are many reasons for the loss of the original archival sources pertaining to Goa. Meanwhile, he reckons that out of approximately 15,000 trials, there were more than 200 death sentences over a period of 250 years.

Further, The Catholic Encyclopaedia too provides valuable statistics about a few Inquisition tribunals in France. At Pamiers, from 1318 to 1324, five out of 24 persons convicted were delivered to the civil power; and at Toulouse from 1308 to 1323, only 42 out of 930 similarly bear the ominous note relictus culiae saeculari. At Pamiers one in 13 and at Toulouse one in 42 seem to have been burnt for heresy, even while these places were hotbeds of heresy and principal centres of the Inquisition, and the period the most active one for the institution.

Even when confronted with such unimpressive numbers, those biased critics make it a point to dub punishments of a bygone era ‘atrocious, ‘barbaric’, ‘cruel’, and so on. They conveniently forget that the same could be said of modern societies that blatantly, whimsically, and sometimes furtively engage in such acts, so unbecoming of purportedly enlightened democracies.

It would therefore be apt to conclude this section by quoting Robert Held, an anti-torture and anti-death-penalty proponent, who puts torture in perspective in his book titled Torture Instruments: “Neither the Roman nor the Spanish Inquisition used methods in any way different from those in everyday use by secular justice everywhere – in this sense it is an error to think of stake, rack and wheel as inventions of or even as attributes peculiar to either. Nothing went on in inquisitional dungeons or places of execution that would have seemed excessive, let alone unusual, to any plebe, prince or burgher of the times.”

The same could be said of the Goa Inquisition – but it is not our intention to elaborate on the subject at the moment. In the forthcoming and final instalment of this three-part series we shall proceed to draw up a general assessment of the redoubtable tribunal in question.

(To be concluded...3)

What was the Inquisition? – 1

The Inquisition has long been made to look monstrous. The Essential Catholic Survival Guide reckons that “to non-Catholics it is a scandal; to Catholics, an embarrassment; to both, a confusion.” Indeed, our generation shies away from its memory or, if caught on the back foot, quickly turns apologetic. It is as though we are under a spell, and this is the handiwork of those inimical to the Catholic Church or at least unaware of the real functioning of the court that was the Inquisition.

The point here is not to whitewash a much maligned institution but to understand its nature. We are before a formal tribunal, not a mere people’s court; that this court had well established procedures, similar to modern courts in many ways and, obviously, following contemporaneous standards of justice, however alien they may seem to our generation. And given the lack of documentation, it is unreasonable to depend on statistics alone to make up our minds about that institution.

Definitions

‘Inquisition’ and ‘Heresy’ are two terms that call for special attention. The first one, from the Latin inquirere, meaning “to inquire”, refers to questioning. Roman law provided for an inquisitorial procedure by magistrates investigating crimes in the absence of formal charges being brought to their attention. After the Empire converted to Christianity in the fourth century, the procedure was employed by emperors from Constantine onwards to investigate heresy and related cases. It behoved the State to uproot this crime which always had socio-political implications; it was only in the second millennium that the Pope intervened, to rein in excesses, by setting up a formal tribunal, though not fully successfully.

Heresy isn’t the same thing as incredulity, schism, apostasy or some such sin against the faith. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines heresy as “the obstinate post-baptismal denial of some truth that must be believed with divine and Catholic faith; or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same.” The doubt or denial involved in heresy concerns a matter that has been revealed by God and solemnly defined by the Church, be it the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, Papal Infallibility, the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary.

It was the task of the Inquisition to ascertain whether a person was guilty of propagating a heresy. Mere holding of wrong notions of Catholic doctrine privately did not attract sanctions from the court. Only a person found to be spreading those views came under the scanner of the Inquisition; and only refusing to be corrected would be considered heretics.

The Inquisition judged Christians; it was thus no torture plan to convert people to Christianity, as it is made out to be. Neither was it an instrument of evangelisation nor were there ever any provisions under Church law for the use of force to convert a person to the faith. The Inquisition aimed primarily to try and reform the accused and win them back to the faith. However, as heresy was an offence under the law, the tribunal, like a parent punishing an intractable child, would have hardened offenders penalised, so as to safeguard the common good. In those days, when Church and State were united, like soul and body, the law holistically catered to the citizens’ spiritual and material welfare. It goes without saying that very often the State overruled the Church, disparaging the spiritual and reformatory aspect and exalting the material and punitive side.

Historical development

Like Moses who was anguished by his people’s worship of the Golden Calf, the Christian Apostles too were deeply concerned about guarding and transmitting the deposit of the Faith undefiled. Unfortunately, not only the early days of Christianity, the whole of the first millennium was riddled with heretical doctrines: the Circumcision heresy (1st c.); Gnosticism (1st-2nd cs.); Montanism (late 2nd c.); Sabellianism (early 3rd c.); Arianism (4th c.); Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism (5th c.); Nestorianism (5th c.); Monophysitism (5th c.); Iconoclasm (7th-8th cs.) and Catharism (11th c.). The Church authorities suffered the consequences of those heresies but, rather than opting for the Old Covenant penalties of death or scourging, simply excommunicated the heretic.

On the other hand, the imperial successors of Constantine, who regarded themselves as masters of the temporal and material conditions of the Church, were persuaded that it was their first concern to protect the State religion. Heresies generated anarchy, so penal edicts (confiscation of property and death) were issued regularly against heretics. A law of the year 407 asserts for the first time that heresies ought to be equated with high treason. For their part, the church authorities in the Christianised states of the Roman Empire refused to invoke the civil power against the heretics.

Ironically, it was the heretics who appealed to the civil power for protection against the Church, and before long complained bitterly of administrative cruelty. At this point, Bishop St Optatus of Mileve defended the civil authority, thus championing for the first time a decisive cooperation of the State in religious questions and its right to inflict death on heretics. This matter wasn’t settled unequivocally given that several ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel. St Augustine was one such bishop who tried to lead back the erring by means of instruction. However, he changed his views, perhaps moved by the incredible excesses perpetrated by the heretics. Yet, it was the desire of the bishop of Hippo to correct them, not put them to death; he wanted the triumph of ecclesiastical discipline, not the death penalties that they deserved.

Meanwhile, as often as the social welfare required it, Christian rulers sought to stem the evil with appropriate measures. In an attempt to save the kingdom and save souls, even distinguished citizens, ecclesiastical and lay, were burnt at the stake. Often there were outbursts of Christian popular sentiment against dangerous sectaries. Sometimes the people blamed the clerical softness in pursuing heretics and so took the law into their hands. Kings and bishops responded by condemning heretics to the stake to prevent the spread of what they called “the heretical leprosy”.

According to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, a definitive strategy came about after Frederick Barbarossa, the powerful king of Germany and Sicily, and Pope Alexander III reached an accord reconciling their respective powers in the Peace of Venice in 1177. This was reaffirmed at the Lateran Council of 1179. In 1184, Pope Lucius III issued the decretal Ad abolendam (‘To abolish diverse malignant heresies’) which some have called the “founding charter of the Inquisition”. It commanded bishops to take an active role in identifying and prosecuting heresy in their jurisdictions. Heretics would suffer excommunication from the Church and be handed over to the civil power to be punished according to the provisions of the common law.

Accordingly, the first Inquisition tribunal was established in southern France in 1184. While death was still not on the cards, punishment was limited to exile, expropriation, destruction of the culprits dwelling, infamy, debarment from public office, and the like. The explicit identification of heresy with treason and its prosecution according to the norms of Roman law was formalised in 1199 by Pope Innocent III. At the Lateran Council of 1215, a relative service was done to the heretics by the introduction of regular canonical procedure to abrogate the arbitrariness, passion and injustice of the civil courts and from the penal codes in Spain, France and Germany.

New Challenges

Although medieval Europe was a society of Catholic kingdoms, adherents of other religions, particularly Judaism and Islam, also lived there. In the first few decades of the thirteenth century, Christian Europe was so endangered by heresy that a formal ecclesiastical tribunal under direct papal jurisdiction became a social, religious and political necessity. Pope Gregory IX established the so-called Monastic Inquisition by his Bulls of 13, 20, and 22 April 1233, appointing Dominican monks as the official inquisitors for all dioceses of France. The Inquisition had jurisdiction only over the Catholic populace; non-Catholics would be hauled up only if found to be perverting Catholic mores. At a time when the people had higher regard for the soul than for the body, heresies were spiritual terrorism to be tackled with vehemence, just as we do against acts of physical violence today.

Broadly speaking, the new tribunals of the Inquisition established in Europe and Asia faced many challenges, some of which are listed below:

a) Catharism (13th century)

These sects were a social menace right from the Byzantine period. They were treated with severity, yet they poured over all of Western Europe. A mix of religions reworked with Christian terminology, Catharism was an umbrella for multiple sects, one of the largest being the Albigensians. By and large, they were not only hostile to the Mass, the sacraments, the ecclesiastical hierarchy and organization, and to the government; their views were fatal to the continuance of human society as they forbade marriage and made a duty of suicide. It was only natural that both Christian and non-Christian custodians of the existing order in Europe should adopt repressive measures against their aberrant teachings.

b) Conversos (15th century)

Pope Sixtus IV empowered Ferdinand and Isabella to set up the Inquisition in Spain in the year 1478, to confront the conversos, pseudo-converts from Judaism (Marranos) and from Islam (Mouriscos). The tribunal turned very fierce even by the standards of the time, so much so that the Pope made efforts to limit the powers of the inquisitors but to hardly any avail. In 1483, a Grand Inquisitor and Supreme Council was appointed to supervise local inquisitorial tribunals, including the later ones in Mexico and Peru. The first Grand Inquisitor, the Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, also exceeded his powers.

c) Protestantism (16th century)

At the turn of the sixteenth century, Europe found itself divided into two ideological blocs: one Catholic and obedient to the Pope; the other, Protestant and opposed to the Pope. After Luther, Calvin and Henry VIII parted ways with the Catholic Church, each began spreading theological ideas that were in conflict with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Their movements began to gain ground in various principalities and kingdoms of northern Europe.

The great apostasy or disaffiliation from the Catholic Church prompted Pope Paul III to establish the Sacra Congregatio Romanae et Universalis Inquisitionis seu Sancti Officii (Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, or the Holy Office), in 1542. It consisted of a commission of six cardinals. They were at once the final court of appeal for trials concerning the Faith and the court of first instance for cases reserved to the Pope. It inaugurated an era of institutionalised inquisitions. Succeeding popes made further provisions for the procedure and competency of the Inquisition of which Pope Sixtus V is regarded as the reorganizer.

In that same year, the Pope made known the first list of books prohibited for their doctrinal content or criticism of the Catholic Church. A more comprehensive Index of Prohibited Authors and Books was brought out after the Council of Trent (1545-63). Later, a separate though related Congregation of the Index updated the list.

d) Paganism (16th century onwards)

This is an umbrella term for beliefs held by polytheistic religions. It applied especially to the religious beliefs of the natives of the colonies held by Portugal and Spain in Asia, Africa and Latin America. King João III of Portugal applied to the Pope for an independent Portuguese Inquisition to deal specifically with threats posed by crypto-Jews in his country. A branch of the tribunal was set up in the city of Goa in 1560 to handle cases relating to the ethnic Portuguese in India and to neo-converts to Catholicism (Jews, Hindus and Muslims) relapsing into their former religions or practising them side by side with Catholicism.

e) Heterodoxy (18th century onwards)

This refers to views that differ from right belief or purity of the Faith, or say, orthodox views. ‘Right belief’ is not subjective, as resting on personal knowledge and convictions, but that which is in accordance with the teaching and direction of an absolute extrinsic authority.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Eventually, Rationalism, or the use of human reason or understanding as the sole source and final test of all truth, began to form the basis of intellectual and scientific activity. It seemed to hold out a promise of dramatic improvement in human life. These tendencies finally led towards religious disbelief, evident in such modes of thought as atheism, agnosticism, materialism, naturalism, pantheism, scepticism, and the like.

New Winds

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the stage was set for republican revolts against European monarchies, beginning in Sicily and spreading to France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire. They ended in failure, repression and widespread disillusionment among liberals.

Nonetheless, winds of liberalism kept blowing hard, unsettling the traditional ways of thinking. Reason continued to score points against faith and displace it across Europe. In fact, religious beliefs began to be equated with blind faith; so faith looked weird when juxtaposed with free private judgement. The view that orthodoxy should be maintained at all cost began to be looked upon with suspicion.

With religion itself relegated to the background, how could a mere institution that stood staunchly for preserving the deposit of the Faith be welcome? Here was a propitious moment for dissenters to quickly and impudently go about their business of discrediting the Catholic Church. The process that had started with the Protestant Revolution gained steam with the French Revolution. It is no wonder, then, that we moderns experience difficulty in grasping the rationale of the Inquisition. The punishments meted out by the tribunal for heresy seem exaggerated, not to say irrational and misplaced.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

How are we to explain the Inquisition in the light of its own period? To do justice to the topic, we need to first have a look at the broad features of the tribunal of the Inquisition.

(To be continued… Part 2)