Accepting the Cross

"Each one of us has a cross to carry. Each one of us would like to be something he is not, to have something he has not, to be able to accomplish something he cannot. We need to let go of being what we are not, having what we have not, and accomplishing what we cannot; this is the way for all of us." - Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira (1908-1995), in 'Reflections on the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ' (https://www.tfp.org/lenten-reflections/)

In touch with the Society for the Defence of Tradition, Family and Property (TFP) for a decade (1989-1999), its Founder's spirituality came easily to mind in my quest for Lenten reading. Here are a few notes on the man whose life can't fail to touch a committed Christian:

Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira was a Brazilian intellectual and Catholic activist. At 24 he became the youngest congressman in Brazil's history and a leader of the Catholic bloc. Valuing his Catholic faith above all else, he turned his back on a political career and served the Church. He taught Modern and Contemporary History at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and was editor of the Catholic weekly Legionário. In 1951, he founded the magazine O Catolicismo and later was a columnist for Folha de S. Paulo, the city’s largest daily.

Dr Plínio (as he was fondly known) was an avowed Thomist, his political ideology anti-Communist. To counter the school of liberation theology and the Cuban revolution, he founded the TFP in 1960. He decried the reforms of the Second Vatican Council but remained devoted to the Chair of St Peter.

Dr Plínio is the celebrated author of fifteen books and over 2,500 essays and articles. Some of his works are: In Defence of Catholic Action (1943); Revolution and Counter-Revolution (1959), a seminal treatise that inspired the founding of autonomous TFP groups in several countries worldwide; The Church and the Communist State: The Impossible Coexistence; and Nobility and Analogous Traditional Elites in the Allocutions of Pius XII, his swan-song.

Dr Plínio's writings have the mark of an intense interior life. He had deep confidence in the Blessed Virgin Mary. An unparalleled twentieth-century crusader for a Christian Civilization, and the final victory of good over evil, he believed in the words of Our Lady at Fatima: “Finally my Immaculate Heart will triumph!”

After Dr Plínio's death, there was a split in the TFP. Eight co-founders took charge of the organization while a large chunk led by Mgr. João Clá Scognamiglio Dias left to set up Heralds of the Gospel. The new group, open to the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, was recognized as an International Association of Pontifical Right, the first one established by the Holy See in the third millennium. They are now present in 78 countries.

Mgr. Dias eventually got back control of the TPF, now devoid of its former glory. Meanwhile, the original co-founders of the TFP set up Instituto Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira (IPCO) to carry on the Founder’s ideology and activity. IPCO is associated with the TFPs and similar organizations worldwide, like the TFP was before their division.

In 1989, the TFP paid tribute to their Founder in a book titled O Homem, Uma Obra, Uma Gesta. Dr Plínio has many other biographies, two main ones being The Crusader of the Twentieth Century, by Roberto de Mattei (1998) and Rencontre avec Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira - Défenseur de la Chrétienté, by Mathias Von Gersdorff (2019). Earlier, regretting the absence of an autobiography, IPCO published Minha Vida Pública (2015), an anthology of writings that throw light on the life and mission of the man.

Knowing Dr Plínio Corrêa de Oliveira’s ideals fills a Christian with hope. His profound analysis of history and world events and his supernatural approach to life - a loving acceptance of the Cross - can uplift the most disheartened soul. To me, a decade with Dr Plínio was worth a lifetime.

Heralds of the Gospel, https://www.arautos.org/

IPCO, https://www.pliniocorreadeoliveira.info/biografia.asp)

A Life in Translation

Quasi-Memoir-1

I was clueless as to 30 September, International Translation Day, instituted two years ago. I got the lowdown from that enterprising, Herald journalist Dolcy D’Cruz: for the purpose of a feature to mark the occasion, she'd sought to know what translation meant to me and how I went about my activity.

‘Translation is a magical thing,’ I said to her, almost instinctively. ‘Not only does it help spread information and speed up business across the globe, it promotes cultural understanding.’

At the back of my mind were Tolstoy and Dostoevksy, Verne and Dumas, Anderson and Grimm, authors whose native languages I didn’t know. And I shed a tear for those who had to depend on renderings of Shakespeare, Dickens and Twain, and why not, Enid Blyton, Agatha Christie and P. G. Wodehouse. I was lucky to read them all in the original, as I was, when it came to my father’s recommendation of a Portuguese staple diet: Júlio Dinis, Garrett, Camilo, Eça, Ramalho, Aquilino, for a novice; and my additions: Pessoa, Torga, Namora, Agustina, Lobo Antunes, and Saramago (with a pinch of salt).

Literary translations have made the world richer. And it’s not literature alone that has depended on translations; even the most disparate subjects like history, medicine and everything in between have benefited from them. If in the early twentieth century, seminarians in our archdiocese had to depend on Latin texts, it wasn’t only because that’s the official language of the Church; there were no translations available in the vernacular!

Even more picturesque was my doctor aunt’s story about the use of French manuals at the Goa medical school, as late as the 1950s: students had soon cultivated the art of reading them aloud in twos or threes, and straight in Portuguese. That was magic!

Early days

As aural memories came gushing, I began to realize that translation had indeed been an organic part of my life. As a child juggling several languages, from Portuguese and Konkani at home, to English, French and Hindi at school, oral translations happened almost as a matter of course. I would reproduce in Portuguese information that I’d received in English, and vice-versa. Mixing of lingos and literal translations were a big no-no, whereas idiomatic language was warmly encouraged.

Yet, translation per se was never the main concern; the accent was on reading good literature and relishing good conversation; it was about having a dictionary at hand and looking up the meaning of an unfamiliar word; it was about finding le mot juste. It was no cakewalk but, looking back, the long walk was so worth it. And a job well accomplished always translated into joy.

After my father’s remark, ‘Languages are an asset; master them while you’re young,’ the next best thing that stuck in my head was Bacon’s famous quote: ‘Reading maketh a full man, conference a ready man, and writing an exact man.’ This was like a command from on high. Or for that matter, F. J. Sheed’s dictum that ‘… minds feed on minds, you cannot nourish your mind with a chop,’ struck me as very sensible.

After handling English texts, ‘ex officio’, on school days, I would spend bits of late Sunday mornings decoding Portuguese texts under my father’s tutelage. By the end of high school, I had begun devoting an hour or so to transcribing All India Radio afternoon news bulletins for O Heraldo. And why? Now it just seems so funny: I’d found this arrangement vital since Goa’s first daily, which was on its last legs, no longer subscribed to news agencies and was starving for news. I also thought it would reassure my father who, after retiring prematurely, lent a hand at the paper – for the love of the Portuguese language and practically for free.

In the public domain

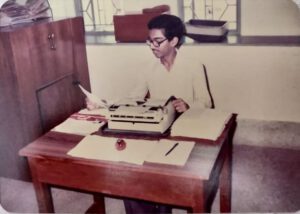

That happened to be my first stint with translation outside the domestic sphere. I didn’t think any good would come out of all that. But, three years later (1983), when I least expected it – I was in the first year of college – the then Jesuit priest Teotonio R. de Souza invited me to work as a research assistant at the newly established Xavier Centre of Historical Research of which he was the director. My task was to create summaries in English of the Mhamai Kamat papers written in Portuguese and French. I was also pleasantly surprised that he’d entrusted me two of his research papers for translation. That we argued playfully about his views is quite another matter entirely!

After my MA at the University of Bombay (1985-87) and a language and culture course at the Universidade de Lisboa (1988), I had a short stint as a lecturer in Portuguese at Dhempe College, Panjim, chiefly, to replace my father who was down with malaria. After a few months, I hesitantly took up an interpreter’s job at the Embassy of Brazil, lured by the national capital. On arriving there, however, I was stunned to see that I would be assisting an eighty year old: Pylades Prata Tibery, a Brazilian national of Greek and Italian ancestry, introduced himself as a ‘juiz de gado’ (cattle judge).

Tibery and I crisscrossed the subcontinent, by road and rail, trailing the Nellore buffalo – a breed that, according to the garrulous old man, Brazil had imported from India in the early twentieth century. Our activity was interspersed with a generous exchange of notes on European and Brazilian Portuguese. While the English of his school days was amusing, even more so were his colourful descriptions of ‘convivial society’ expressed in his native Brazilian.

Well, I could hardly be buffaloed by a more outlandish task even if handsomely paid, as indeed I was. It marked the beginning and the end of my honeymoon with translation/interpretation as a full-time job... On my return to Goa, I took up teaching as a career. After the initial hiccups, I found fulfilment in interpreting my students’ thoughts and feelings, and translating their ignorance into knowledge, their anxieties into hope, and their ambitions into reality! Translating and interpreting could now only be side gigs, mostly to oblige friends and family. For instance, I liaised at a couple of wine festivals and carried out humdrum legal translations, among other things. Even these I could no longer endure when I finally had my eyes set on translating literary, historical and spiritual texts. That would surely be a balm to my spirits.

Literary translation

Sometime in 1995, a brief encounter with Editor Arun Sinha of The Navhind Times provided that go. Keen on setting up a literary page to step up his paper’s Sunday magazine, ‘Panorama’, he suggested I work on Goan short stories written in Portuguese. I did produce quite a few translations, but alas, inevitable changes on the home front constrained me to discontinue the series.

But in spite of everything, mine has continued to be a life in translation, of which the Herald article gives a glimpse (see the link below).

(To be continued)