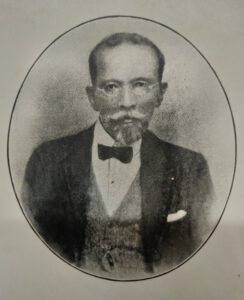

Mariano Saldanha: um distinto académico goês

Ao conhecer um grande senhor nascido apenas duas décadas após a Revolta dos Cipaios[1], senti a corrente do passado transitar suavemente para o presente. Esse notável goês, que emigrara para Portugal no ano da Grande Depressão, passou os anos de jubilado em Goa e faleceu após Portugal ter reconhecido formalmente a conquista indiana da sua terra natal. Era quase centenário, porém, isso é o mínimo que se pode dizer de alguém que marcou na história de várias outras maneiras.

Primeiros anos

Mariano José Luís de Gonzaga Saldanha, vulgo Mariano Saldanha, nasceu em 21 de Junho de 1878, filho de Luís José António Assis André de Saldanha, de Ucassaim, e de Ana Joaquina Ermelinda da Pureza e Dias, de Socorro. Era médico que se fez indologista e pesquisou a história, língua, literatura e cultura indo-portuguesas. Era sobrinho de dois irmãos padres, Joaquim José Santana de Saldanha, fundador de uma escola na aldeia, e de Manuel José Gabriel de Saldanha, professor do Liceu de Nova Goa e autor da clássica História de Goa[2], em dois volumes.

Em 1905, Mariano Saldanha formou-se em medicina e farmácia pela antiga Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa e depois trabalhou como médico em Goa e a bordo de navios. Entretanto, sentindo-se vocacionado para o estudo de línguas indianas, aprendeu o sânscrito com monsenhor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, na Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, e frequentou cursos na Escola Colonial. Na época de Herculano em Portugal, e de Cunha Rivara e de Dalgado em Goa, não era raro um profissional do ramo da ciência interessar-se pelas humanidades; contudo, no caso de Mariano Saldanha, a mudança foi total.

Em 1915, foi nomeado professor de marata e sânscrito no referido Liceu. No ano seguinte, publicou O Curso de Sânscrito Clássico,[3] que compreendia o seu discurso inaugural sobre a importância desta língua e os documentos relativos à criação do curso em questão. Em 1926, traduziu o poema Mêghaduta, ou a mensagem do exilado,[4] de Kalidasa, poeta e dramaturgo da Índia antiga, anotado, prefaciado e acompanhado do original sânscrito.

Docente em Lisboa

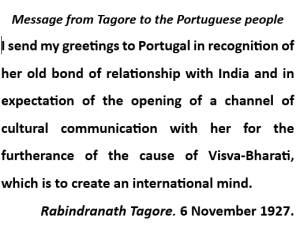

Em 1929, Mariano Saldanha mudou-se para Lisboa, agora como professor de sânscrito na sua alma mater, ocupando o lugar que ficara vago desde a morte de monsenhor Dalgado em 1922. Trazia ao povo português uma mensagem de amizade de Rabindranath Tagore, Prémio Nobel da Literatura, quem visitara em Shanti-Niketan em 1927, atraído pela ideia de harmonizar a cultura indiana antiga com ideias internacionais. Após a morte do grande poeta e pedagogo bengalês, Saldanha recordou o encontro na memória que publicou com o título “O Poeta de uma Universidade e a Universidade de um Poeta”[5].

Em 1946, Mariano Saldanha era nomeado subdirector do Instituto de Línguas Africanas e Orientais da Escola Superior Colonial, onde veio a leccionar o sânscrito e o concani até se aposentar em 1948. Publicou a Ultima Lectio[6], e depois da jubilação, um manual, Iniciação na Língua Concani, “especialmente organizado para o ensino, de carácter prático, da língua concani” na referida Escola.[7]

Voltou a Goa em 1950, onde permaneceu cerca de quatro anos, tendo sido depois convidado pelo Governo da Metrópole a participar na elaboração de um projecto de ensino público em concani, para Goa, e na transmissão de programas radiofónicos nessa língua para a diáspora goesa na África Oriental Britânica e no Golfo Pérsico.[8]

Aproveitou a oportunidade para continuar as suas pesquisas na capital.

Concanista de renome

Além de docente, Mariano Saldanha foi um investigador de renome, principalmente como concanista, ou seja, na ‘Concanologia’[9]. No 50.º aniversário da morte do ilustre estudioso, cumpre recordar o seu precioso contributo para os estudos da Língua Concani, que tanto amou e pela qual tantos esforços despendeu.

Dedicou-se sobremaneira à pesquisa fundamental da língua da sua terra natal. Visitou bibliotecas, arquivos e museus de Goa, Lisboa, Évora, Braga, Paris, Londres e Roma, vasculhando livros e manuscritos, à procura da mais pequena pista. Escreveu exuberantemente, com artigos em revistas científicas e em jornais.

Em 1936, escreveu uma valiosa história da gramática concani, no Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, que se destacou também pelo pioneirismo.[10] Em 1943, escreveu uma série de artigos sobre “Questões do Concani”, no Heraldo, um diário panginense.[11]

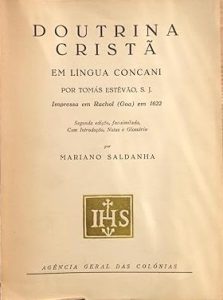

Em 1945, publicou a 2.a edição, fac-similada, com introdução, notas e glossário, de Doutrina cristã em língua concani (1622)[12], de Thomas Stephens, missionário jesuíta britânico, que foi o primeiro inglês a chegar ao subcontinente indiano e pioneiro no estudo das línguas indianas.

Em 1950, descobriu três códices na Biblioteca Pública de Braga, a saber, n.os 771, 772 e 773. As primeiras duas relatam, em concani, histórias tiradas das epopeias indianas, respectivamente, o Mahabharata e o Ramaiana; o último contém três dezenas de poemas em marata, também da mesma fonte; e todos eles escritos em caracteres romanos.[13] Prontamente informou outros interessados, inclusive um dos seus dissidentes ideológicos, A. K. Priolkar.[14]

Cultura goesa

Mariano Saldanha tinha consciência da rara singularidade de Goa, no meio do vasto subcontinente indiano, como síntese cultural do Oriente e Ocidente e detentora de um modo de vida próprio. Por isso, em 1947, mal que sentiu soprar os ventos da mudança política, o seu profundo amor à terra natal levou-o a dar um sinal de alerta.

Fê-lo primeiro por meio de um ensaio intitulado “A lusitanização de Goa”, na revista Rumo.[15] Em Goa, a Repartição de Estatística e Informação reimprimiu-o,[16] e em Portugal, a Agência-Geral do Ultramar traduziu-o em grande parte para o livro Portugal Overseas and the Question of Goa[17]. Ainda hoje é muito citado.

O douto professor sentiu-se feliz como presidente da 5.a edição do Konkani Porixod, conferência a nível pan-indiano, realizada em Bombaim, em 1952. O seu «Odhiokxachem Bhaxonn»[18], ou discurso presidencial, foi publicado em caracteres latinos, que recomendava para o concani moderno. Nessa ocasião afirmou que o concani é uma língua independente do marata e que deveria ser o veículo de instrução primária em Goa.

A propósito do referido Porixod, deu largas ao seu conceito histórico da língua concani, na memória intitulada “A língua concani: as suas conferências e a acção portuguesa na sua cultura”, publicada no Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama.[19] Duas décadas antes abordara esse tema no IX Congresso Provincial de Goa[20].

Nesta fase da vida, expressou-se também sobre a música ocidental em Goa[21]; sobre a imprensa seiscentista aí estabelecida, pioneira na Ásia[22]; e sobre a literatura purânica cristã[23], frisando sempre a identidade marcante de Goa.

Os seus trabalhos retratam-no como investigador escrupuloso, crítico exigente e polemista temível.[24]

Últimos anos

Em 1958, Mariano Saldanha voltou de vez ao solar da família e à aldeia natal que ainda mantinha o charme rústico de outrora. Aceitou como facto consumado o desfecho que teve o conhecido Caso de Goa e, em 1967, regozijou-se com o resultado do Opinion Poll, ou referendo. Infelizmente, na vida particular, foi, por um lado, vítima das leis de expropriação do período pós-1961, e por outro, privado das suas últimas economias que havia confiado ao seu antigo empregado em Portugal. Para agravar, saiu prejudicado na reforma devido ao novo contexto político.

Apesar disso, a vida continuou. Com excepção da gota e da surdez, gozava de boa saúde e manteve-se lúcido até ao fim da vida. Escrevia para os órgãos públicos, recebia visitas e aceitava convites para reuniões académicas e outras. E ainda na provecta idade, costumava celebrar o seu aniversário, cercado de familiares e amigos da velha-guarda.

Manuel Leitão, filho do seu antigo cuidador Francisco, recorda-o como um católico devoto, de coração bondoso e leitor assíduo de jornais da língua portuguesa (O Heraldo e A Vida), concani (Vauraddeancho Ixtt, Sot e Uzvadd) e marata (Gomantak), de entre os publicados em Goa. Mantinha relações com os respectivos directores e colaboradores, e no interesse destes, e ansioso por estabelecer padrões elevados, corria com tinta vermelha os jornais concani.

O erudito era consultado em assuntos relativos a Goa e ao concani. Não admira que a sua rica biblioteca com centenas de livros, microfilmes e manuscritos, tivesse atraído jornalistas e investigadores, entre os quais Carmo Azevedo, que, escrevendo no mensário Goa Today, o apelidou de “enciclopédia viva de coisas goesas”[25], bem como os activistas do Konkani Bhasha Mandal. A família doou o acervo ao Xavier Centre of Historical Research, de Goa.

Apesar das cãs, o bom e velho solteirão era paciente com os jovens. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho deleitava-se com o saber e a sagacidade do seu tio-avô. Graças à sua prodigiosa memória, este contava-lhe prontamente histórias sobre Akbar, Xivaji e outros vultos indianos, que faziam parte dos currículos escolares do pós-1961; e ela incluía-as nas suas provas.

Tive eu, como menino de 6 anos, o meu primeiro encontro com o professor já então nonagenário. No Hospital do Asilo, em Mapuçá, havia ele discursado e descerrado o busto do Dr. Ernesto Borges, seu sobrinho-neto, oncologista de renome mundial e que cedo pagou o tributo à morte. Foi um momento emocionante. Eu acompanhava a minha tia Maria Zita da Veiga, que havia experimentado o seu toque curativo. Após a cerimónia, perguntaram ao professor se se importaria de esperar um pouco mais pelo transporte para casa. Impressionou-me a sua resposta: “Claro que me importo”. E logo a gargalhada que se seguiu desdizia tudo….

É impossível dizer tudo de uma vez sobre Mariano Saldanha, distinto académico goês que muito honrou a sua terra. Faleceu em 23 de Outubro, mês Mariano, do ano de 1975, quase desconhecido das novas gerações e um tanto esquecido pelas velhas. Deve ser, porém, evocado com gratidão e estudado com atenção, tal como todos os vultos da nossa terra, para que se facilite assim uma transição harmoniosa do passado para o presente.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 37, Novembro-Dezembro 2025, pp. 33-37)

Referências

[1] Revolta armada, realizada entre os anos de 1857 e 1859, em oposição ao domínio britânico, a qual de Meerut passou para Delhi, Kanpur e Lucknow, cidades no norte da Índia.

[2] 2.ª edição. Nova Goa: Edição da Livraria Coelho, 1925-26. A primeira edição intitulava-se Resumo da HIstória de Goa, publicada em 1898, em um único volume.

[3] Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1916.

[4] Nova Goa: Casa Editora Livraria Coelho, 1926.

[5] Revista de Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa, N.º X, 1943, pp. 57-77.

[6] Anuário da Escola Superior Colonial, Ano XXIX, 1947-48, Lisboa, 1948. Também nos Estudos Coloniais, Lisboa, Vol. I, 1948-49.

[7] Parte I: Noções Gramaticais. Lisboa: 1950. Não consta que tenha saído a Parte II.

[8] “Mariano Saldanha: a centenary tribute”, de Teotónio R. de Souza, in Indica, Vol. 15, N.º 2, Setembro de 1978, pp. 135-138.

[9] Termo por ele cunhado para se referir às “publicações relativas ao concani”, veja-se Monsenhor Dalgado. Esboço bio-bibliográfico. Lisboa: 1933, p. 11.

[10] "História da Gramática Concani," Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 8 (1935–37), pp. 715-735.

[11] Heraldo, de 14, 16, 24, e 30 de Março de 1943.

[12] Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1945.

[13] Os códices ora encontram-se na biblioteca da Universidade do Minho, veja-se The Old Konkani Bhārata. Volume 1: Introduction, de Rocky Miranda (Margão: Asmitai Pratishthan, 2019), p. xi.

[14] Mais tarde, Panduronga Pissurlencar, José Pereira, António Pereira, Lourdino Rodrigues, Rocky Miranda e outros serviram-se dos mesmos códices para os seus trabalhos de pesquisa.

[15] Rumo, Revista de Cultura Portuguesa. Ano 1, Agosto e Setembro, 1946, pp 343-366

[16] No. 6 da série da Colecção de Divulgação e Cultura.

[17] Lisboa: Agência-Geral do Ultramar, s.d., pp 41-58

[18] Konknni Porixod. Panchvi Boska. 1952. Odhiokx: Dr. Mariano Saldanha, Hachem Bhaxonn. (Mumboi: Fr Napoleon Silveira, 1952) É o único texto seu expresso inteiramente em concani.

[19] N.o 71, 1953.

[20] Congresso Provincial da Índia Portuguesa (Nono), Nova Goa: Tip. Bragança, 1931.

[21] “A cultura da música europeia em Goa”, Separata da Revista do Instituto Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos, Vol. VI (1956).

[22] “A primeira imprensa em Goa”, Separata do Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama, N.º 73, 1956.

[23] “A literatura purânica cristã e os respectivos problemas linguísticos e bibliográficos”, Separata do Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama, N.º 82, 1961.

[24] Veja-se As investigações de um gramático (Lisboa: Tip. Carmona, 1933), em que escalpela a obra Elementos gramaticais da língua concani (Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1929), de José de S. Rita e Sousa, antigo professor da Escola Superior Colonial; e Aditamentos e correcções à monografia O Livro e o Jornal em Goa (Bastorá: Tip. Rangel, 1936) e Ainda a monografia O Livro e o Jornal em Goa (Bastorá: Tip. Rangel, 1938), nas quais interpela o professor liceal Leão Crisóstomo Fernandes.

[25] “A Date with Dr. Mariano Saldanha”, in Goa Today, p. 13.

A Distinguished Goan Scholar

After one has met a grand old man born just two decades after the Sepoy’s Mutiny, history cannot but look like a thing of the present. He migrated to Lisbon in the year of the Great Depression. He spent his post-retirement years in Goa and died several months after Portugal formally recognised the Indian takeover of his native land. He was a near-centenarian, but that is the least of his claims. He made history in more ways than one.

Dr. Mariano Saldanha (1878-1975) of Ucassaim was a physician-turned-indologist who studied history, language, literature, and culture. He was the nephew of Fr Gabriel de Saldanha, the author of the classic História de Goa. In 1905, he graduated in medicine and pharmacy from Goa’s iconic medical school. After a few years of professional practice, he left for Portugal to study Sanskrit under Mgr. Dalgado at the University of Lisbon. It was not unusual then for a man of science to show an interest in the humanities, but his was a total switch.

On his return in 1915, he taught Marathi and Sanskrit at the Panjim Lyceum and translated Kalidasa’s Meghaduta into Portuguese. In 1929, he was back in Lisbon, now a professor of Sanskrit at his alma mater. He proudly carried a message of friendship to the Portuguese people from Tagore, whom he visited in Shantiniketan. In 1946, he was appointed as the deputy director of Escola Superior Colonial’s Institute of African and Oriental Languages. He taught Konkani there until his superannuation in 1948.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

On the milestone anniversary of this distinguished scholar, we recall his precious contribution. Mariano Saldanha’s affinity to history and languages was evident from an early age. He pursued fundamental research in the Konkani language in Lisbon. He spent countless hours in libraries, archives, and museums, sifting through books and manuscripts with a scrupulous eye for the smallest clue.

In 1945, Professor Saldanha produced an annotated facsimile edition of Thomas Stephens’ Doutrina cristã em língua concani (Christian doctrine in Konkani, 1622). In 1950, he unearthed sixteenth-century Konkani and Marathi manuscripts in Braga’s public library. The love of truth drove him forward not only to discover but also to share the fruits of his discovery. He did so even with his ideological dissenters, such as A. K. Priolkar.

In 1952, Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth Konkani Parishad. Being a strong votary of Konkani in the Roman script, his address was published accordingly. Curiously, this is his only text written in Konkani. When he sensed the political winds of change, he began to emphasise Goa’s distinctiveness in the Indian subcontinent, through its language, Konkani; the Lusitanian influences on its culture; the roots of Western music; its pioneering printing endeavours, and its Christian Puranic literature.

After his death, his family gifted his large book collection to the Xavier Centre of Historical Research. His microfilms and manuscripts show his discipline and patience. He was a member of several academic bodies and published his writings in journals and newspapers. They depict him as a thorough academic researcher, an exacting reviewer, and a formidable polemicist.

However, nothing prevented the good old bachelor from being patient with the youngsters. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho told me of how she used to lap up information and pearls of wisdom from her granduncle. While, thanks to his prodigious memory, he recounted stories with ease, she happily fit those anecdotes about Akbar, Shivaji, and other Indian greats, in her school answers.

At age 6, this writer had an unforgettable first encounter with the then-nonagenarian professor. He had unveiled the bust of world-renowned oncologist Dr. Ernest Borges, his grandnephew, at Asilo Hospital, Mapuçá, and addressed the gathering. It was an emotional moment. After the ceremony, the Professor was asked if he would mind a slight delay in his ride home. His stern reply was, ‘Yes, I mind.’ But then, the delayed laughter said it all.

For their part, the citizenry today should mind that the memory of Goan notables is often taken for a ride. They deserve better from our civic, academic, and governmental bodies if we are to achieve a seamless transition from the past into the present.

Banner: Dr Mariano Saldanha delivering the presidential address at the Fifth Konkani Parishad, Bombay, 1952

This article was first published in Herald, Panjim, on Dr Mariano Saldanha's 50th anniversary of death, 23 Oct 2025

A Pope of Great Promise

The outcome of a papal conclave is always a surprise. Not only is the august assembly held cum clave, meaning under lock and key, the huge number of cardinal electors – who double as candidates – makes it impossible to guess who will emerge as the pontiff. Even though well before a conclave begins, different agencies float names of the papabile, these have only indicative value. The cardinal electors make their final decision on the spur of the moment, by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. That’s how unpredictable a papal conclave can be.

The secular world, however, looks at it as a numbers game or a power struggle. No doubt, historically, Europe has had the largest number of Popes (235/266), with Italians outnumbering them all (217). Yet it cannot be said that the papal office is racially defined. For instance, in the early centuries even the so-called Dark Continent produced Popes, whereas the white New World got its first one as late as the twenty-first century.

Furthermore, while 15 countries have produced Popes till date, including tiny Albania way back in the eighteenth century, longtime superpower USA had to wait until the twenty-first to have their very own top man at the Vatican. He possibly comes as a divine reward for the resurgence of faith and devotion (particularly with the National Eucharistic Revival) in his native country; but he has not trumpeted his national affiliations.

Finally, there will always be countries not making the grade, but surely no country or race will be deliberately excluded. So, no matter which part of the world the Pontiff comes from, he never fails to surprise.

First Impressions

The rise of Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost as an American is as good a surprise as it would have been if he were an Indian or an Australian. So long as he steers the Barque of Peter with faith and divine authority – that is all that matters.

That is why, even before I got to see the man in the Loggia delle Benedizioni, I felt the blessing of the name he had assumed: Leo XIV. Much as we may say ‘What’s in a name?’, a name is not without historical and cultural significance. It is selected after much reflection and with a purpose. Presently, it symbolises strength, courage, power and the determination to begin a course correction. It represents the divine kingship and majesty of Christ. It stands for the teaching authority of Jesus, who is the ‘Lion of the Tribe of Judah’ (Rev 5:5).

After a quick minute of great anticipation, the French window finally opened. I saw the man in traditional vestments. What most impressed me was his calm and gentle demeanour, humility and unpretentiousness. He came across as a simple and sincere prelate. He seemed authentic and accessible, straightforward and down-to-earth, with the ability to call a spade a spade. While he looked at the cheering crowds with tenderness, he was far from being over the moon with delight.

An unmistakable change in that iconic balcony! I said to myself, let bygones be bygones; the past is behind us – the present and the future are all that matter. The Loggia of Blessings was to me a window on the future. I began to imagine Leo XIV restoring all things in Christ. Just then, I heard the Vicar of Christ's deeply evocative greeting – Peace be with all of you! – ‘the first greeting of the Risen Christ, the Good Shepherd who gave His life for God's flock.’

Like a tender father, the Pontiff wished ‘this greeting of peace to enter your hearts, to reach your families, and all people, wherever they are, all of the people, all over the earth.’ He followed it up with reassuring words: ‘God loves us, God loves you all, and evil will not prevail! We are all in the hands of God.’ Calling disciples of Christ to join hands and move forward, he focussed on the Divine Master alone, saying: ‘Christ precedes us. The world needs His light. Humanity needs Him as the bridge to allows it to be reached by God and by His love.’

And then, lo and behold, there came words and phrases that had almost fallen into disuse: his was a call to be ‘faithful to Jesus Christ, without fear, to proclaim the Gospel, to be missionaries.’ Pledging his service as a true son of Saint Augustine, he turned the people’s gaze to ‘that homeland that God has prepared for us.’ A man of deep faith and experience indeed.

The Holy Father had a special greeting to the Church of Rome and to his diocese of Chiclayo, in Peru, ‘where a faithful people accompanied their bishop, shared their faith and gave so, so much to continue being a Church that is faithful to Jesus Christ.’ Words of gratitude, of encouragement, of zealous devotion are what we heard from the Loggia that blessed night.

But that is not all. His Holiness reminded the gathering that it was ‘the day of the Supplication to Our Lady of Pompeii. Our Mother Mary always wants to walk with us, to be close, to help us with her intercession and her love,’ and befittingly ended his first Urbi et Orbi blessing with a Hail Mary. I felt immensely comforted.

Tasks Ahead

The Lord our God has favoured us with Pope Leo XIV, thanks to the prayers of many zealous souls. For over a decade now, the likes of German Cardinal Gerard Müller, Guinean Cardinal Robert Sarah, US Cardinal Raymond Burke, German Bishop Athanasius Schneider; theologians, lay individuals and groups had been sounding the alarm bell about the waves of the world mercilessly buffeting the Barque of Peter. Providentially, the new Captain will steer the drifting ship back on course.

To my mind, the tasks ahead are many. Meanwhile, to maintain our integrity as Catholics, we must turn the spotlight on three fundamental issues. First, we must stress the importance and non-negotiable nature of the Sacred Tradition and the Holy Magisterium of the Church. As Cardinal Müller recently said, ‘the question is not between conservatives and liberals but between orthodoxy and heresy.’

Secondly, we must address the wrong notion that even some of us Catholics have of the Church’s mission. It is our duty to make Christ known, present, and active in the world. We must lead people toward a deeper relationship with Him and with one another. The Church is not a ‘humanitarian organisation doing social work’ but a spiritual lighthouse that affords a view of eternal life.

Thirdly, how can we recover from the identity crisis that ails us? It is fuelled by gas lighters, some of whom have infiltrated the Church. It is the proverbial smoke of Satan clouding our minds and making us look for validation from the secular world. The antidote is to appreciate, love and be grateful for the treasures of our Faith and our Church.

Let us entrust these issues and many others too long to list here to the leadership and wisdom of Pope Leo XIV and be continually surprised and amazed by God's work in our midst. No matter how hard it is to figure it out, he occupies the Chair of Peter by the express will of God, Who has said: ‘So is My word that goes out from My mouth: It will not return to Me empty, but will accomplish what I desire and achieve the purpose for which I sent it.’ (Is 55: 11).

Long live Pope Leo XIV!

Banner: https://www.thetablet.co.uk/news/first-urbi-et-orbi-blessing-of-the-holy-father-leo-xiv/

Prevost at the Vatican (2023) https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20250508-pope-leo-xiv-profile-robert-prevost-from-peru-missionary-to-first-american-pontiff

Mario is Forever

When contacted by Dolcy D'Cruz of Goa's leading English-language daily Herald, for comments on the public screening of the documentary "The World of Mario... Seriously Funny!", https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Fj-KEN2kQI , researched and scripted by me for Doordarshan Goa, here is what I said, in reply to the journalist's questions:

On challenges faced

Mario had the world for his canvas, so the main challenge was to be able to truly cover his creative life in a short documentary.

Identifying the right talking heads and liaising with them was another challenge. His sister Fatima gave us valuable inputs. And we also got on board film-maker Shyam Benegal, Indian adman Gerson da Cunha, architect Gerard da Cunha who owns the Mario Gallery, and many others.

https://epaper.heraldgoa.in/oHeraldo?eid=1&edate=22/10/2024&pgid=52727&device=desktop&view=2

On his relevance

Mario is a curious case of a self-trained artist who had different styles, worked with different mediums, and across the print and electronic media.

It is a civic duty to pay homage to the greats of our land. Mario loved Goa and worked towards preserving our culture and heritage. Many tourists used to come here in the hope of finding ‘Mario’s Goa’ but often they were disappointed on seeing that Goa had changed a lot.

On a personal note

Working on Mario took me back to my Bal Bharati textbook. As kids, few must have known that the illustrations were done by a great Goan artist.  Then, I saw him and his dog in the pages of the Illustrated Weekly. Finally, I met Mario face to face for the first time in 1987, at the Gulbenkian in Lisbon. On his exhibition catalogue he scribbled, ‘For Oscar, Saudades, Mario’, and suddenly I felt I’d known him forever.

Then, I saw him and his dog in the pages of the Illustrated Weekly. Finally, I met Mario face to face for the first time in 1987, at the Gulbenkian in Lisbon. On his exhibition catalogue he scribbled, ‘For Oscar, Saudades, Mario’, and suddenly I felt I’d known him forever.

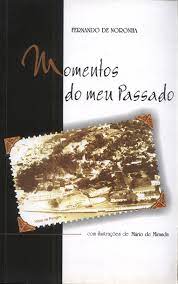

Also, he very kindly illustrated my dad Fernando de Noronha’s memoirs, Momentos do meu Passado, which he said had brought back nostalgic memories of his youth in Goa.

To me, those saudades remain – of a gentleman with a twinkle in his eye, an unassuming genius, a lovable character, just like all those that he has immortalized in his illustrations and cartoons.

-o-o-o-o-

Here are a few pictures of the event, which comprised the first public screening of the "Stories and Documentaries" series at DD Goa auditorium, inauguration of the digital screen and felicitation of the documentary team, and superannuation farewell of a DD Goa veteran:

Governor of Goa addressing the audience

Governor of Goa addressing the audience

Pics, courtesy: Bambino Dias, Thomas Rodrigues Lorraine de Noronha, Miguel Furtado and Emmanuel de Noronha

Life and Times of Alfredo Lobato de Faria

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, thank you for having us!... We cannot but notice the number of art objects surrounding you…. You are a real artist!

A.L.F.: I don’t deny that, but at the same time I don’t wish to praise myself… Really, I do like art; it has been my passion.

O.N.: Did you ever think of going to an art school?

A.L.F.: Well, I couldn’t. I wanted to become an artist, but didn’t have the money. I studied pharmacy, and stayed on there…

O.N.: But you still made time for art! It was your pastime…

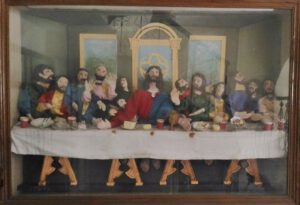

A.L.F.: Yes. That ‘Last Supper’ there was my last frame.

O.N.: What was your magnum opus?

A.L.F.: I painted 14 frames depicting the Way of the Cross. It meant wood work, canvas, paints, and all that. Fourteen frames isn’t child’s play!

O.N.: Where are they now?

A.L.F.: They are in the chapel of Nossa Senhora da Piedade, São Pedro. When I realized that the chapel didn’t have the Via Crucis series, I gifted the frames. I don’t know if they are still there… I don’t say this because I did them, but doing fourteen frames wasn’t easy…

O.N.: But they remain preserved for posterity!...

A.L.F.: Well, well, history, too, forgets…

CARNAVAL

O.N.: We recently had the Carnaval in Goa… Any memories of the Carnaval of past years?

A.L.F.: This is no Carnaval, nor were the earlier carnival [parades] the real Carnaval… The original Carnaval was bacchanalian. .. They would drink to the point of losing control of their actions… to the extent that Nero, who was a terrible emperor, banned it, for men and women would enter the parade almost in the nude, with only a fig leaf to conceal the genitals…

O.N.: And what about the Goan Carnaval?

A.L.F.: Ours is no Carnaval either… it’s plain commerce. Just commercial publicity in the parades…

O.N.: As far as I know, you were one of those who stitched costumes for the floats? Any recollections?

A.L.F.: I was mostly the one making most of the costumes. I would sit down and keep stitching those costumes. My house would be strewn with rags. I was passionate about those things, their costumes, etc…

PANJIM

O.N.: Talking a little about Pangim: did you always live here?

A.L.F.: No; I first lived in Ribandar, and then came to Pangim. When my daughter Maria de Fátima was in the third year of Lyceum, Ribandar felt a little far away. There was no public transport; and although I had a motorcycle, it wasn’t good enough for three people. So I shifted to a house behind Fazenda.

O.N.: Tell us something about personalities that you remember from your Lyceum days?

A.L.F.: I had distinguished teachers. Prof. Leão Fernandes: he was knowledgeable and knew the art of teaching…. And then another teacher who would write on the origins of the language… he gave good lessons on the Portuguese language: Salvador Fernandes. Once he called me for a Latin lesson. I was weak. He looked at me and said, ‘Oh, I understand why you are weak… You’re wearing shoes with crepe soles. No stability.’ Since then I started studying Latin, and he gave me 12 out of 20 marks, which coming as they did from Salvador Fernandes was a lot, like 20 marks from some other teacher. And after he retired, I wrote him a thank-you letter, for all that he’d taught us through newspapers and even over the phone… I would phone him sometimes… And that other one was a savant, Egipsy de Sousa. He could teach any subject. He used to teach us chemistry, about gases, methane, the gases of the marshes, ethane, and all those bonds…. They were teachers who knew how to teach.

O.N.: You were a regular contributor to Heraldo, weren’t you?

A.L.F.: I started a page in Heraldo under Dr António Maria da Cunha. Later, in O Heraldo under Prazeres da Costa, I started a page called ‘Página dos Novos’. He was a very demanding person. He would immediately strike off… but he was truly a writer. He would take his pen and write, write and write… And then came Carmo Azevedo, who reviewed my book, Sombras…

O.N.: That’s right! We have to talk about your book of poems, titled Sombras... Why ‘Shadows’?

A.L.F.: Why? Because everything was full of shadows then, there was no joy; everything was dark, hence mine was a book of shadows…

O.N.: Who did the cover?

A.L.F.: I painted the cover depicting a harp and a woman…

FAMILY

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, could you tell us a word about your family, please!

A.L.F.: Lobato de Faria is an illustrious family. I don’t say this because it’s mine. The family belongs to the nobility and founded the morgadio of Nerul, the first morgado being Manuel Freire Lobato de Faria, who came to Goa in the 17th century. Nerul belonged to him. He made history! Imagine, he caught Arya, who was a bandit that would infest the areas of China and Goa, and nobody could catch him. He caught him, handcuffed him and sent him to Portugal. I belong to that noble family.

O.N.: So, later, the family settled in India…

A.L.F.: Yes. Since then it has been living here. He was a nobleman and fidalgo cavaleiro (knight) of the Royal House who had blood relations with Nuno Álvares and King Dom João I! Well, today … I could still use my coat-of-arms, which I have, but…

O.N.: It’s a well known family…

A.L.F.: And that lady in Portugal…

O.N.: You mean Rosa Lobato de Faria, writer and actor, belongs to the same family…

A.L.F.: Yes. She is from another branch. He was supposed to be sterile, but had 7 children and proceeded to different places. One of them remained in Portugal, and Rosa is from that branch.

CENTENARIAN

O.N.: Mr Lobato de Faria, now that you’ve touched 100, what thoughts are uppermost in your mind?

A.L.F.: My dear friend, whoever has crossed 100, what else should he expect?... I would say I am happy with my God and with friends. I thank God for my family…. What God did was something very special. He handed life to humanity and He remained above. Indeed, that was the best thing He could do: offer His own life for humankind.

O.N.: Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria, you are a man of faith. You’ve lived to be a hundred, in faith. You are now surrounded by love and care from your daughters, four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. You’ve lived your life all the while helping to improve other people’s life. I thank you for your hospitality and bid you goodbye, wishing you good health and happiness. Thank you!

A.L.F.: Thank you!

(Mr Alfredo Lobato de Faria passed away in April 2018, two months after this interview, at the age of 101 years. He lies buried in the cemetery of St Agnes, Panjim)

Use the following link to listen to the original interview in Portuguese on the YouTube channel of Renascença Goa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ylH2bkNzA

First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Jan-Feb 2021

A Última Conversa com Percival Noronha

Numa tarde chuvosa (1 de Julho do ano passado), quando de súbito me lembrei do Sr. Percival Noronha[1], não hesitei em terminar a minha sesta dominical. Um distinto cavalheiro – culto, agradável, e que me estimava – daí a dias iria completar a bonita idade de 95 anos… Urgia, pois, falar com o grand old man de Pangim.

Quando liguei para a sua casa, ouvi logo um ‘Estou!’ inconfundível. Na linguagem do Sr. Percival, esse estar era o mesmo que estar disponível! ‘Pode o Óscar vir quando quiser’, disse com a amabilidade que o caracterizava. Estava sempre pronto para um papo, e desta vez seria como nunca dantes: radiodifundida na minha rubrica mensal, Renascença Goa… (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRK2PimgTmo) Saí então rumo às Fontaínhas, acompanhado do meu irmão Orlando que trataria das fotos.

Era um prazer ir à residência do Sr. Percival (‘Ajenor’, nº E-426, à Rua Cunha Gonçalves). Também nos cruzámos, por centenas de vezes, em concertos, conferências, exposições de arte, e não menos em casamentos e funerais. Um senhor da velha guarda, era cumpridor dos seus deveres sociais e cívicos. Apesar da nossa diferença etária, a conversa corria como um rio de águas claras, pois o Sr. Percival era não só envolvente mas também apreciador dos méritos dos seus contemporâneos e estimulador dos talentos dos mais novos.

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Por muito curioso que pareça, vi o Sr. Percival Noronha, pela primeira vez, no longínquo ano de 1969. Foi isso na sede do Governo, ou seja, no Palácio do Idalcão, a antiga residência oficial dos Vice-reis e governadores portugueses (1759-1918), o qual a partir de 1961 passara a denominar-se Secretariat. Aqui trabalhava também uma tia minha, Maria Zita da Veiga. E conservo a grata memória de o Sr. Percival nos convidar ao Café Real para o chá das cinco. Como o restaurante apinhado de gente, demorámos no seu Volkswagen Beetle, onde vieram chávenas de chá para os colegas e um refresco para o menino que os acompanhava!

Diga-se de passagem que eu admirava o seu automóvel, preto, parecendo sempre novo, tal como o seu proprietário. Este, sempre vestido de bush shirt ou camisa safari, percorria os cantos e recantos da cidade, que conhecia como a palma da sua mão. É que Percival e Pangim se pertenciam um ao outro: foi dos melhores cronistas da capital, do seu ethos e do seu ritmo, que descreveu em bela prosa.[2] E fê-lo com autoridade, mesmo porque presenciou nove décadas, ou seja, metade da história dessa urbanização,[3], de forma que hoje se torna difícil imaginar o nosso Pangim sem o Sr. Percival Noronha.

Cargos oficiais

Feitos os estudos liceais na capital, o Sr. Percival Noronha entrou para a administração pública, em 1947. Trabalhou, primeiro, nas Obras Públicas, passando depois para os Serviços da Estatística e Informação. Quando esta foi desagregada, o distinto professor e escritor António dos Mártires Lopes levou-o consigo para os novos Serviços de Turismo e Informação de que este acabava de ser nomeado chefe. O Sr. Percival nunca se esqueceu dos belos tempos do Liceu e do funcionalismo que passou sob a alçada directa desse seu antigo professor liceal: confessava que essa relação fora fundamental em nutrir a sua paixão pela história e cultura.

Quando se deu a mudança do regime politico, em Dezembro de 1961, o Sr. Percival era chefe-adjunto dos Serviços da Informação, reportando ao governador-geral Vassalo e Silva. Em Junho de 1980, a visita do simpático governador coincidiu com as comemorações do 4.º centenário da morte de Luís de Camões em Goa. Vinha a título pessoal, mas nem por isso a visita deixou de suscitar controvérsia.

Decorreu-se o pior da cena no Azad Maidan (‘Largo da Liberdade’), a antiga Praça Afonso de Albuquerque. Aqui, à certa distância, vi o antigo governante a ser interpelado por alegados actos de comissão e omissão do regime português em Goa.[4] O embaraçoso incidente atalhou-o o Sr. Percival Noronha, que, na qualidade de chefe de Protocolo do Território de Goa,[5] estava incumbido de acompanhar o ilustre visitante.

Antes dessa data, com a limitada bagagem de conhecimentos de inglês auferidos no Liceu, e língua essa que logo veio a dominar, o Sr. Percival Noronha ocupou outros cargos importantes na administração indiana. Foi sub-secretário das indústrias, minas, trabalho, saúde e turismo. Entre muitas outras iniciativas suas, os hospitais do Asilo em Mapuçá e o Hospício de Margão passaram a subordinar-se à Direcção de Saúde. Desenvolveu as zonas de Calangute, Colvá, Mayém e Farmagudi, e ideou os desfiles do Carnaval e Xigmó; teve papel preponderante no arruamento Campal-Miramar e na arborização do Parque Infantil; e foi um dos responsáveis pela realização da grande Feira Agrícola em 1970. Ora, possuidor dum raro espírito de autocrítica, não ocultava as faltas que houvera no planeamento e execução dessas suas propostas.

Não admira que o Sr. Percival Noronha tivesse sido um solteirão muito cobiçado. Passou, porém, a vida a cuidar da veneranda mãe, vindo a aposentar-se apenas um ano após a sua morte. Era igualmente dedicado à vida burocrática, passando horas a fio à mesa do gabinete, até para além das horas regulamentares. Um funcionário desse quilate podia facilmente esquecer-se de si próprio, como foi, na verdade, o caso do Sr. Percival Noronha.

Vida de aposentado

Teria sido diferente a sua vida depois de aposentado em 1981? Mudou de actividade, sim, mas o expediente não mudou de volume. Dedicou-se, a tempo inteiro, às matérias por que tinha propensão natural: a arte, a história e a astronomia.

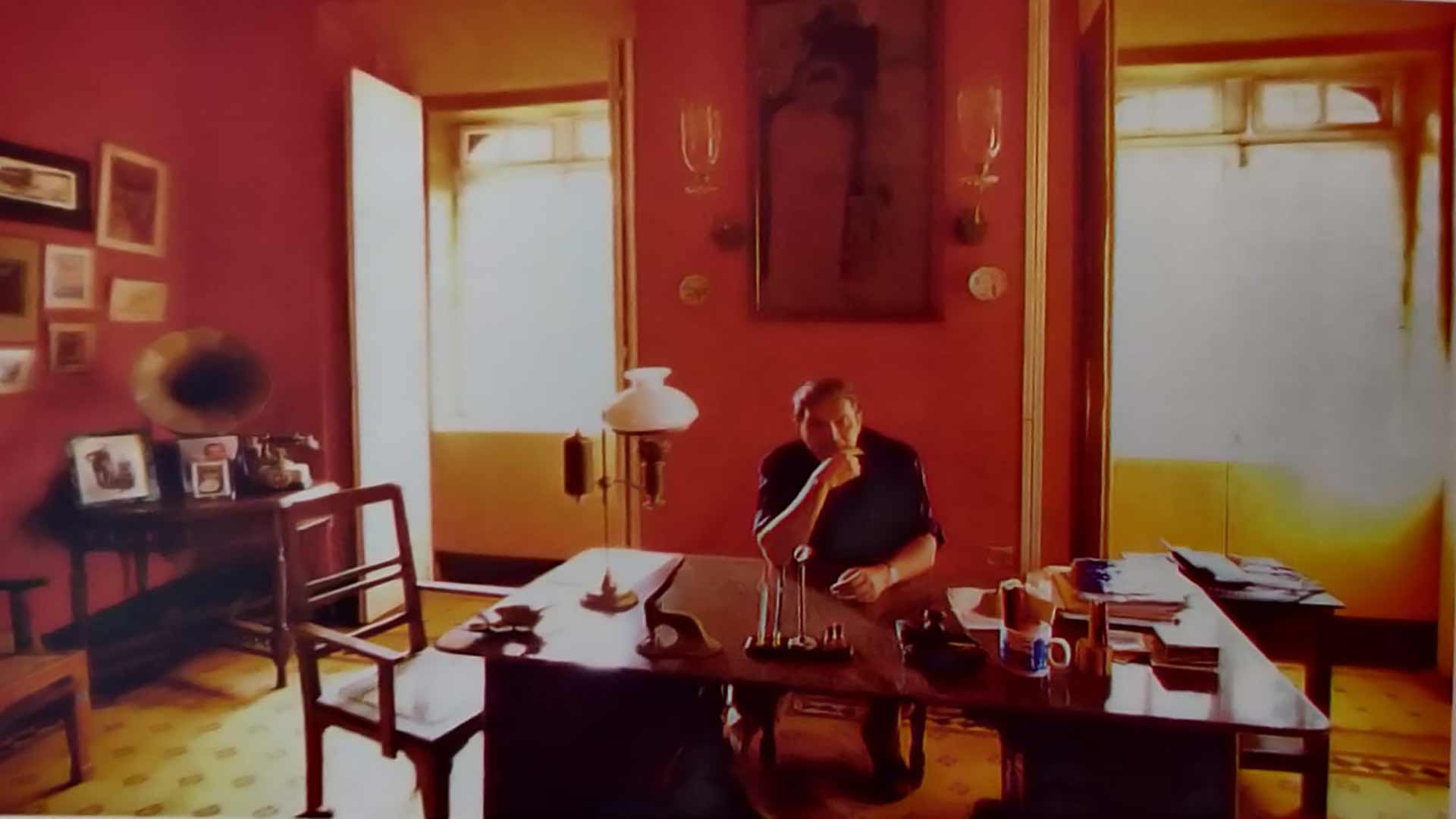

Começou por dotar a sua residência com mobiliário de estilo tipicamente indo-português. Efectuou-se grande parte dessa obra no rés-do-chão do seu prédio, o qual havia sido confiado ao conhecido carpinteiro Zó. Disse-me, em mais de uma ocasião, que gastara nisso quase todas as suas economias. Também é verdade que todo dinheiro lhe era pouco quanto se tratasse de comprar objectos de arte e livros.[6] Assim, a casa se viu transformada em verdadeiro museu-arquivo que deveras honra o histórico bairro das Fontaínhas.

O Sr. Percival não parou por aí: tomou a peito vários assuntos de interesse público. Inspirado pelo alto funcionário (e depois governador) K. T. Satarawala, no ano de 1982 abriu um ramo da Indian Heritage Society em Goa e foi professor convidado da Faculdade de Arquitectura. Exerceu o cargo de secretário daquela organização não-governamental que, em colaboração com a Town and Country Planning Department, preparou um relatório sobre os prédios e sítios de importância arquitectónica no território de Goa. Foi também tesoureiro do INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) em Goa.

Esses organismos continua a desempen har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

har o importante papel de alertar a opinião pública e de sugerir medidas pela preservação do património cultural mas falta-lhes o Percival, que em crónicas de jornal e trabalhos de pesquisa, se esforçara por esclarecer os conceitos relativos à tradição goesa.[7] Tinha subjacente um apelo por que os goeses se pusesssem à altura da sua história e cultura, que fazia questão de interpretar como verdadeiramente indo-portuguesa. Sendo a Velha Cidade, sem dúvida, o berço dessa cultura, era natural que a antiga capital do Império Português no Oriente fosse a menina dos seus olhos.[8] E pelos serviços prestados à divulgação e defesa da cultura de língua portuguesa e da identidade indo-portuguesa em Goa o cronista do nosso passado foi agraciado pela República Portuguesa com a Ordem do Mérito (2014).[9]

Embora o Sr. Percival Noronha fosse indiferente em matéria religiosa, nunca hostilizou a Igreja. Pelo contrário, reconhecendo o papel desta no progresso espiritual e material dos povos, colaborou com as entidades eclesiásticas. Em 1986, quando da visita do Papa João Paulo II, participou entusiasticamente na preparação do evento. E, em 1994, foi membro fundador do Museu de Arte Cristã que ora se acha no Convento de S. Mónica.

Esse goês de gema era um arco-íris de saberes, tratando tanto da arqueologia como da astronomia com a mesma facilidade. Fundou a Association of Friends of Astronomy (AFA)[10], em 1982. Este organismo, além de vir a publicar uma revista mensal, Via Lactea, editada pelo fundador, abriu, em 1990, um observatório astronómico público – o primeiro do seu género na Índia – com o apoio do Departamento de Ciência, Tecnologia e Meio-Ambiente, do Estado de Goa.

O Sr. Percival Noronha viveu uma vida sem artifícios – plain living and high thinking. Foi um líder cultural que criou à sua volta uma pleiade de jovens com decidida propensão pela história, arqueologia, arte e astronomia. Na sua casa, onde funcionavam os dois organismos que criou, recebia jornalistas, pesquisadores e outra gente interessada. Teimava em alertar a geração nova sobre o grave estado de bancarrota civilizacional em que a sua amada Goa estava a descambar. Esses recursos humanos e hábitos salutares sendo o maior legado do Sr. Percival Noronha, tem razão a Fundação Oriente em apelidá-lo de “Um Goês Exemplar”, num livro que publicou em sua homenagem.

Na verdade, é a vida intelectual que o entusiasmava, contribuíndo também para a sua saúde física. A sua roda de amigos da velha data[11] nutria a saudade pelo passado enquanto a geração nova o desafiava com projectos futuristas. Era um desses amicus certus, que tratando-se de algum sem-vergonha, falava, tipicamente, com ironia e sorriso escarninho. Mas não vou sem frizar que a todos desejava o bem, e para uma vida saudável recomendava-lhes uma medida de moog grelado por dia! Antes da prótese da anca, em Abril deste ano, esteve relativamente lúcido e ágil.

Última conversa

96 anos da vida. Dir-se-ia mesmo que o Sr. Percival Noronha teve sete vidas. Nos últimos anos era seu costume, quando adoecesse, anunciar a sua morte e daí a dias estar em pé! Era como que tivesse um sistema imunológico como o do gato persa, de que gostava. Não era motivo para recear, pois, quando ouvi de novo que o Amigo estava em declínio. Tive, porém, empenho em conversar com ele demoradamente.

Às 4,30 da tarde, o Sr. Percival tinha já à mesa o bule de chá e bolachas. Dormira a sesta e estava pronto para uma conversa. A rapariga, às ordens, sentada lá no fundo da sala. E parecia tudo como dantes...

Foi quando notei que o venerando ancião tinha o cabelo despenteado, a barba por fazer, e faltava-lhe a placa de dentes. Nunca o vira assim… Os apetrechos de trabalho estavam lá todos, arrumadinhos, nas estantes e armários, dum lado da sala de jantar, onde costumava passar grande parte do tempo a trabalhar. Também isso não estava como dantes... E reflecti também que desta vez o meu anfitrião que viera ele à janela, como era seu costume, deitando para mim a chave da porta principal… Tudo isso indicava que a sua vida ia afrouxando. Fiquei triste.

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

Por outro lado, animou-me o facto de ele mandar vir esse ou aquele livro ou pasta que até sabia bem onde estava. Já dava sinal de certa lucidez... Continuando a conversa notei que já não era o mesmo Percival Noronha de 1969; ou o de 1999, quando me recomendou que concorresse para a tradução do livro de Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes[12]; ou o de 2004, quando me deu um depoimento sobre a Velha Cidade[13]; e nem mesmo o de 2016, quando me falou sobre o meu tio-avô[14]. Não, não era o mesmo Percival Noronha!

No entanto, ia falando sobre o seu currículo escolar e profissional; as suas actividades depois de aposentado; sobre Salazar (cuja inteligência e honestidade admirava) e o 18/19 de Dezembro; a administração, portuguesa e indiana; os cursos e conferências que realizou nas universidades da Ásia e Europa; o futura da língua portuguesa em Goa; a cultura goesa e a distorção da sua história; os seus amigos e as pessoas que admirava; e a vida em Pangim: tudo isso, entre muitos outros assuntos, e não necessariamente nessa ordem de ideias.

Nos últimos meses, vi-o, várias vezes, debruçado no peitoril da varanda, qual abencerragem a observar a vida que corria lá fora, e com a cara de quem pensa: Quantum mutatis ab illo… Barbudo, lembrava Abraão, personagem de primordial importância para as comunidades à sua volta. E com aquele cabelo a voar e ele a fitar o firmamento, assemelhava-se à figura de Einstein…

Também lá do alto do Céu ouvirá – no último domingo do mês de Novembro deste ano – a última entrevista que concedeu cá na terra. Foi a minha última conversa com o Sr. Percival Noronha.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] De nome completo, Percival Ivo Vital e Noronha (26.7.1923 –19.8.2019), filho de António José de Noronha, de Loutulim, e de Aurora Vital, de S. Matias.

[2] “Panjim: Princess of the Mandovi” (2002); “Fontaínhas: vivendo com o passado”(2001); “Fontaínhas: the Tale of Panjim’s Latin Quarter” (2003), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015)

[3] A vila de Pangim foi elevada à cidade com a denominação de Nova Goa, por alvará de 22 de Março de 1843, o qual lhe outorgou todos os privilégios de que gozavam as cidades de Portugal Continental.

[4] O incidente impulsionou a minha primeira intervenção jornalística em forma de uma carta ao director dum jornal de Pangim – “Our Honoured Guest”, in The Navhind Times, 12/6/1980.

[5] Na altura, cumulava este cargo com o de director da administração das Obras Públicas.

[6] Doou a sua casa ao sobrinho Francisco Lume Pereira, de Verna, onde Percíval Noronha faleceu, e os livros doou-os à Universidade dos Açores e à Krishnadas Shama Library, de Pangim; e os diapositivos, ao Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino.

[7] “Christian Art in Goa” (1993); “Indo-Portuguese Furniture and its Evolution” (2000); “Priceless Christian Art” (2004), e “Goan Artisans” (2008), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[8] “Levantamento arqueológico da Velha Goa e tentativas para a sua conservação” (1989); “Old Goa in the context of Indian heritage”(1997); “Um passeio pela Velha Cidade de Goa”(1999); “A Capela de Nossa Senhora do Monte, em Velha Goa” (2001), ), in Percival Noronha: Um Goês Exemplar (Fundação Oriente, 2015).

[9] Recebeu ao todo 16 galardões de proveniência vária.

[10] http://afagoa.org/about_us.html

[11] Entre outros, António dos Mártires Lopes, Aleixo Manuel da Costa, Maria de Jesus dos Mártires Lopes, Alcina dos Mártires Lopes, Artur Teodoro de Matos, Luís Filipe Thomaz, Teotónio de Souza, Rafael Viegas, Nandakumar Kamat, Satish Naik.

[12] Tradition and Modernity in Eighteenth-Century Goa (Manohar, New Delhi & Centro de HIstória de Além-Mar, Lisboa, 2006)

[13] Old Goa: A Complete Guide (Panjim: Third Millennium, 2004)

[14] Castilho de Noronha: por Deus e pelo País (Panjim, Third Millennium, 2018)

Fotos de Orlando de Noronha, com excepção da da condecoração (e-cultura.pt) e da do lançamento do livro (Fundação Oriente)

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série, Número 1, Maio/Dezembro de 2019 https://issuu.com/jmm47/docs/revista_da_casa_de_goa_-_ii_s_rie_-_n1_-_maio-dez_

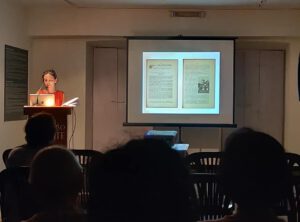

All about Amor

Maria do Carmo Piçarra’s talk at Fundação Oriente, Panjim, was titled “Behind the Portrait of Antunes Amor, Educator and Pioneer of Cinema in Goa”. A researcher at Instituto de Comunicação da Nova (ICNOVA), Lisbon; assistant professor at University of the Arts, London (UAL); and a Fundação Oriente scholar, Piçarra holds a doctorate in Communication Sciences. She is a film programmer; author of several publications, among them Azuis Ultramarinos. Propaganda colonial e censura no cinema do Estado Novo (2015) and Salazar vai ao cinema (2006, 2011), and principal editor of (Re)Imagining African Independence. Film, Visual Arts and the Fall of the Portuguese Empire (2017).

Piçarra contextualised a painting titled “Mr. Amor. The Portuguese Agent” (1917) from the Trindade Collection on permanent display. That striking piece of art by the Bombay-based Goan painter António Xavier Trindade (1870-1935) was gifted to the Foundation by Dr Marcella Sirhandi, a friend and biographer of the artist.

Piçarra spoke of Amor’s cinematographic forays in Macau, where he screened his first amateur movie. She also mentioned the films he made about school life, history, and so on, while in Goa. A strong defender of the pedagogical and propagandist uses of cinema, Amor had several of his films shown in local halls.

The precious little I already knew of Manuel Antunes Amor (1881-1940) I had heard from my father a quarter of a century ago; I was now surprised to see him again! Trained in Germany in the early twentieth century, Amor (‘Love’, in Portuguese) was a self-opinionated gentleman whose tenures as primary school inspector in Goa (1916, 1922) were mired in controversy.

Finally, Piçarra's remark that Amor was particularly suspicious of lawyers reminded me of that high-profile polemic he had with Joaquim de Araújo Mascarenhas (1886-1946), a Goan legal eagle who doubled as Portuguese language teacher at Liceu Nacional de Nova Goa. A lethal combination it proved to be.

An article titled “O ensino primário e a incúria do Estado” ('Primary school education and State neglect') that Araújo Mascarenhas wrote for the maiden issue of the monthly Boletim de Educação e Ensino (April 1927) made Amor see red. He wrote a censorious rejoinder, “Sem autoridade nem razão” ('Devoid of authority or reason'), in the very next edition.

Araújo Mascarenhas dashed off a point-by-point rebuttal. The Boletim’s editorial board that comprised primary school teachers declined to publish it, possibly fearing the inspector's wrath. It led the redoubtable polemist to bring out a volume titled Resposta a uma provocação ('In Response to a Provocation').

Sadly, the Boletim folded up in August that year, but not before the long series of events had vitiated the atmosphere. No wonder the very gifted Mr Amor was someone many Goans loved to hate.

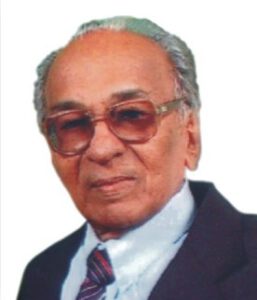

Dr Adélia Costa: Goa's angel of mental health

She was Goa’s best known neuropsychiatrist. The first to turn the spotlight on mental health in our land, she served the community professionally for half a century. She now lives a quiet retired life amidst close family in Miramar.

Few would know that Maria Adélia Peres e Costa, who turns 90 today, is Goa’s first neuropsychiatrist. After graduating from the Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa, she pursued specialised studies in Lisbon, becoming the first lady neurologist in Portuguese territory. On her return to Goa in 1958, she was appointed the first director of the freshly set up state-run Abade Faria hospital, now Institute of Psychiatry and Human Behaviour.

A research paper in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry states that the young director was appalled at antiquated methods of handling lunatics and bizarre practices of interning political prisoners alongside those patients! She highlighted the anomalies and suggested corrective measures, in a report that the Portuguese local government promptly accepted. At once deputed to source modern equipment and medicines from France, she returned with many goodies for the so-called “children of a lesser god”.

They eagerly waited to meet that doctor who spoke little but did a lot, that healer whose initial reserve quickly gave way to a smile and some curative banter.

Brand-new infrastructure alone can do no wonders, much less do away with stigma attached to a mental hospital. So it was the range of humane practices inspired by Dr Adélia that finally led to an attitudinal change in the staff and the public. Patients were brought out from custody to an open and friendly environment. The hospital staff became skilled at grooming the inmates and administering standard medications. Relatives and friends, too, eventually began to minister to their kin with tender love and care. A gentle revolution in healthcare got started.

By March 1962, however, Dr Adélia had sensed that the gentle revolution would not be sustainable. The resolute lady was on her final round of the hospital wards while, thousands of miles away, Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest exposing Nurse Ratched’s antics in an Oregon psychiatric hospital, was making waves for all the right reasons.

Meanwhile, Dr Adélia flew out to Portugal, this time to study psychiatry, and on her return set up private practice in Panjim. Before long, Dr Adélia became a household name, a name synonymous with mental health. Her residence and clinic was always teeming with patients, many of them from beyond the borders of Goa. They eagerly waited to meet that doctor who spoke little but did a lot, that healer whose initial reserve quickly gave way to a smile and some curative banter. Never mind the labels “nervanchi dotor” and “pixianchi dotor” contrived by the man in the street, medical cases were sure to find ethical solutions at the hands of this angel of mental health.

Dr Adélia had the makings of a model physician. Not only was she on top of the latest news and trends in medicine, she worked tirelessly, disregarding her personal ups and downs. That she could recall case histories with ease spoke volumes about her commitment. A cool head, a good listener, she was empathetic to the mental and material needs of the patients, and they never felt rushed. Even as it was striking that she always put on the white coat, it was even more so that she meticulously filed her patient treatment cards to the very end. She exuded self-confidence, yet humility was her abiding trait. And all of this came from her passion to make a difference in the lives of others.

There was an obvious connection between Dr Adélia’s faith and her life as a medico. She has been a contemplative in action

In addition to being a remarkable professional, Dr Adélia is a remarkable senhora. While fully dedicated to her clinical responsibilities, she also saw to her other obligations. After a hard week’s toil she would drive down to Loutulim in her Fiat and, later, a first-generation Maruti-Suzuki (both in classy shades of green) to spend weekends with her mother. And amidst all the chores, she still found the time to read and have a chat. And yes, she stopped to pray. She was more than just a Sunday Catholic. Her participation in the early morning Way of the Cross at the city church on Good Friday is one picture that has stayed with me since I first saw it.

There was an obvious connection between Dr Adélia’s faith and her life as a medico. She has been a contemplative in action, living out beautifully what the twentieth-century savant Alexis Carrel called “a journey of the soul towards the realm of grace.” May that marvellous cycle live on. A role model for many, Dr Adélia has spent an entire lifetime alleviating human suffering, by treating and reassuring others. She can feel blessed with the assurance that she lives in their grateful hearts and minds.

(An abridged version of this article was published in The Goan, Panjim, 27 August 2018)

http://epaper.thegoan.net/1792134/The-Goan-Everyday/The-Goan-Everyday#page/4/1

Remembering Prima Maria

November 1987. I was all of twenty-two years old and had landed in Lisbon. Shortly after this I phoned a relative for whom I’d carried a little parcel from her sister Genoveva (to whom I became a sobrinho by marriage but remained first a primo, via Curtorim). Her name was Rita Maria Gomes. I’d never met her before; yet she sounded so warm that I promptly accepted her lunch invitation. Her brother Nicolau stopped over to collect the item, early the next morning, shaking me out of my jet lag: he was my only visitor at Hotel Berna, Campo Pequeno, where I’d put up in the first three days of my year-long stay in Portugal.

After my maiden Sunday Mass na terra de Camões, I headed for Carcavelos, half an hour’s journey by train from Cais do Sodré. Usually shy at a first meeting, I was nonetheless eager to see my mother Judite’s “Guirdolim cousins”.

At Oeiras, on a near-empty platform, Primo Amâncio Frias Pinto and I easily spotted each other. As he comfortably drove me home in his white Renault 10, his down-to-earth style put me at ease. And then, when Prima Maria and the family welcomed me, I noticed the glow on her face: she had taken a shine to Judite’s son. My gracious hostess had very thoughtfully invited three primos still new to me: Noémia and her children Lena and Stuart. I instantly identified the senior one (now a much-loved Tia) as daughter of Primo ‘Picu’ Stuart, who I’d been very fond of as a child… Now here was a heady mix of Neurá and Curtorim/Guirdolim, and it made my day!

I have no photographs of that memorable coming together. That was altogether another age, the pre-digital age! I vividly remember, however, that the apartment was bathed in sunlight. Prima Maria had the table laid de rigueur and served a full course meal. It wasn’t easy, but she did it! And, yes, she kept up an animated conversation, centred on Goa, our relatives and friends.

It was still a bright and pleasant afternoon when Prima Maria suggested we take a stroll in the colourful feira nearby. And soon it began to feel like home. When evening came and Primo Amâncio (who’d been my father Fernando’s contemporary at Casa de Estudantes) dropped me off to the station, I felt a sudden pang of saudade…

..........................................................................

August 2018. Years after my unforgettable passage to Portugal, I met the simpático casal at their ancestral house at Ararim, Socorro – which, meanwhile, I’d become familiar with as the home of my wife Isabel’s maternal aunt Bernadete married to Terêncio Frias Pinto. Prima Maria made a few more trips to Goa, travelling solo after her husband’s demise. Last year, we crossed paths at Panjim’s Immaculate Conception church. That’s when I quickly fixed up a lunch appointment; and unable to meet up at home, we decided on a thali at the Fidalgo.

How can we forget the people who’ve made us happy at some time or other in our lives? I’m glad I started off by recalling the lovely moments spent with her family – oh my God! – three decades ago...

As for her, she was soaked in memories. She smiled wistfully, reminiscing about her spinster days in Goa and as a young wife in Mozambique, and gave me the lowdown on her life as a widow.

A grandmother of two, pretty even at eighty, Prima Maria was proud of her Gomes ancestors who made it big in Portugal. She spoke ardently about the Veiga-Gomes kinship, and – surprise of surprises – she pulled a neat set of notes and sepia out from her handbag to confirm that the doctor-politician Pestaninho da Veiga (1849-1901), the physician-writer A. X. Heráclito Gomes (1864-1934), and the poet Mariano Gracias (1871-1931), who died in Lisbon, were indeed first cousins! Prima Maria was thus a third cousin of my mother’s; her children Rui and Lara, and I, sit a step below.

Needless to say, formal relationships are not everything; it’s the level of friendship that counts. For instance, when the infant Maria Rita da Veiga, died of bronchopneumonia, a day prior to the arrival of a baby in the Gomes household, this new-born was baptised Rita Maria. The noble gesture speaks volumes of the oneness of spirit that proceeds from life built around shared values! In any case, a rarity in our day and age, this episode endeared the new Maria very especially to my mother who, aged 3½ years, had been confused and shaken by the disappearance of her immediate junior sibling.

There are, on the other hand, myriad incidents over which one has no control whatsoever; one gets to join the dots only much later. Consider my mother’s passing, at the age of 83½ years, precisely on Rita Maria’s eightieth birthday! Doesn’t this say something about the communion of saints that often goes unnoticed even by practising Catholics?

Life never ceases to amaze us. Prima Maria, despite her aches and pains, travelled to Canada, New Zealand and Australia – aching to connect with friends and relatives – whereas I’d failed to get in touch with her brother Heráclito in Porto. I’d thought of him, even in the midst of São João celebrations there, but it had remained just that – a thought… That I finally got to meet him, thirty years later, on Facebook, is another matter entirely! We now stand in awe of this gift from cyberspace.

My first – and last – lunch invitation to Prima Maria inevitably ended, but not before my mobile phone camera – sensing our connectedness – clicked away, trying to discover facial resemblances between kith and kin… And it was saudade once more…

Still a sunny afternoon, much like the one at Carcavelos, I drove Prima Maria to ‘A Pousada’, a pensão she was staying at, in the city’s charming São Tomé ward. We said our goodbyes, and I left. When I called up after a month, I got no answer… Heaven knows why!

Até sempre, Prima Maria!

Papa - 1

Fernando do Carmo Heitor de Noronha, filho primogénito de Tomaz Nuno Francisco Carmo de Noronha, de Neurá-o-Grande, e Leonor Zoraide do Rosário e Sousa, de Aldonã, nasceu em casa dos avós maternos. Casado com Judite Teresa da Veiga, de Curtorim, tinha o Curso Complementar dos Liceus (de Letras e de Ciências).

Funcionário público (do Quadro da Administração Civil e, mais tarde, do da Polícia Judiciária), depois de aposentado, nos anos 70, esteve ligado a O Heraldo, o último diário da língua portuguesa em Goa, fundando depois, com outros, em 1983, o semanário A Voz de Goa, que veio a ser o último periódico expresso no idioma luso. Dedicado à língua portuguesa, entre os anos 1985-88, foi professor-convidado de Português no Xavier Centre of Historical Research (Miramar/Porvorim) e no Dhempe College of Arts & Science, Miramar.

Em 2002, publicou o seu primeiro livro, Momentos do meu Passado, sob a chancela da casa editora Third Millennium, fundada pela família e de que era parceiro, sendo talvez a única casa a publicar livros em português nesta parte do mundo. Um segundo volume de memórias – Goa tal como a conheci – será lançado dentro de meses. E ainda tem vários inéditos.

Era pai/sogro de Óscar/Isabel, Ilídio/Imelda, Ivo/Tânia, Sávio/Olívia e Orlando/Tina, e avô de quinze netos (7 rapazes e 8 raparigas).

(Apontamentos prestados à Revista Ecos do Oriente, de Loures, Portugal, cujo director, Mário Cirilo Viegas, publicou, com acrescentamentos que não estão integrados no presente texto, sob o título de ‘Fernando de Noronha: Um Indo-Português de Caráter’, na edição de Jul-Set de 2011 (Ano VI, N.º 23), com capa e editorial dedicados a meu Pai)