"My dream is to see Goa’s Civil Code extended to the Indian Union," says M. S. Usgaonkar

ON: What does the ‘dream’ that you talk of in the Preface to your book mean to you and to our territory?

MU: Well, before I talk about my ‘dream’ I would like to clarify that when Seabra’s Civil Code [1867] was published, it did not have the chapters that I am going to stress on, as these were fruits of the Republic in 1910. Thus, the Portuguese Civil Code was a product of the Constitutional Monarchy; the law of Marriage, the law of Divorce and the law for the protection of children were specialties produced by the Republic. The Portuguese Civil Code did not have the concept of divorce; it simply dealt with the absolute separation of property.

ON: According to you, why didn’t Seabra introduce Divorce and, instead, dealt only with Separation? Was it through the influence of the Catholic Church?

MU: I don’t think so… The concept did not exist at the time. Divorce evolved much later.

ON: So, in 1910 all communities had access to the law of divorce...

MU: Yes; but the Church prohibited it, because one of the Articles states: those marrying through the Church are not entitled to divorce. This provision was later stuck down by our Courts because one could not discriminate between two communities.

ON: Well, the Civil Code would not discriminate between communities, yet it appears that the usages and customs only of certain communities were safeguarded in the Code....

MU: This was not about the usages and customs; this was a part of the law. Divorce (earlier it was Separation) was made part of the special legislation that came into force in 1910, after the Republic.

ON: Could you throw light on the usages and customs that were safeguarded?

MU: They were excluded in 1880, that is, before the Republic.

ON: Some examples of what was safeguarded…

MU: For example, one could marry at a predetermined age, which was reduced. Later, this law was extended to the Catholics also, because they pointed out that there was a tradition or custom to marry at an early age and that was permitted by the State.

ON: What was the age?

MU: The girl could marry at the age of fourteen.

ON: And the boy?

MU: At the age of sixteen.

ON: Is it true that members of the Hindu community were permitted to have more than one wife?

MU: There was a restriction. It required the consent of the earlier wife; and she had to be childless. Only then the second marriage was permitted; but this was struck down by the Portuguese law in the year 1952, on the grounds that polygamy had long been abolished.

TRANSLATING THE CODE

ON: Let’s talk a little about your translation: how long did it take you?

MU: Not long… just twenty years.

ON: Twenty years!

MU: Well, the total number of Articles of the Civil Code is 2538. There is also the Civil Procedure Code and miscellaneous legislation regarding the usages, customs and others which total up to more than 4000 Articles.

ON: So, yours is a translation of the whole of the Portuguese Civil Code…

MU: Not only of the Code but also of other laws that were published later…

ON: … which are connected to the Civil Code and to the Civil Procedure Code…

MU: Yes, the Civil Procedure Code, too, which has 1580 Articles. The reason for translating both the Codes is that the Civil Code alone is not sufficient; the Civil Code provides only the substantive aspect of law, but the enforcement or implementation is done through the Civil Procedure Code. Courts and others must follow the Civil Procedure Code, so the Codes are complementary.

The Code of Civil Procedure was repealed in the year 1939; the whole of it was the work of Prof. Alberto Reis and it was in force at the time of Liberation… At a conference at Simla, organized by advocates from the Indian Union, I had the opportunity to highlight the advantages of the Portuguese Civil Code and how it serves to decide cases much faster.

ON: But in Goa today only a part of the Portuguese Civil Code is in use, isn’t it?

MU: It was in use, but later it was gradually substituted by corresponding Indian laws.

ON: Which are those laws?

MU: For example, the Transfer of Property Act, Contract Act which formed an integral part of the Civil Code stood pro tanto altered.

ON: So, today, the Code is in use mainly regarding family laws…

MU: Yes, the law of marriage and divorce is unaltered. Fortunately, what existed here was repealed neither by the Union of India nor by the State government, except that every time an Indian law was introduced, the respective provision of the Civil Code was repealed. For example, the law of pre-emption… when an individual sells his right without giving preference to the co-owner. This is not provided for in the same way under the Indian law. The problem which arose was to see whether this provision of Portuguese law prevails or not. The courts said that it does prevail since a similar provision does not exist in the Indian Civil Code.

ON: In Portugal, is the same Civil Code still in use?

MU: No, it was changed entirely, in 1966, influenced by the Germanic theory… When Napoleon Bonaparte prepared a Code and appointed persons, he said that the Code had to use simple language, such that the public could easily read it. In contrast, the Germanic jurists said that eventually only the jurists should read the Code and not the public.

GOAN CONTRIBUTION

ON: This Code is a Portuguese legacy, but Goa is also connected to the Code, through a Goan – Luiz da Cunha Gonçalves – who has contributed a lot, thanks to his Treatise on Civil Law... Would you like to throw some light on this jurist?

MU: Of course! He writes in the Preface to the first volume: “More than sixty years have elapsed since the publication of our Civil Code, but whereas in the interim period many treatises and commentaries have been published in the main countries of Europe, especially in France and Italy, here in Portugal the scientific work in this branch of legal science has been scarce, fragmented, superficial, nothing to compare even with the treatises of French classics, nothing on a par with the modern treatises. It was therefore imperative that alongside our Civil Code, one of the best in the civilized world, an intensive and extensive work should emerge, of the kind that I have referred to. Nobody will fail to acknowledge it, and convinced that I will be rendering good service to the Portuguese legal science and the country, I will not hesitate to try and execute the work, presuming that I will be helped by ingenuity and art.”

ON: It is evident from the host of names featuring in your book, right from the Chief Justice of the Bombay High Court to the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India, that your book and your translation of the Portuguese Civil Code did evoke a lot of interest…

MU: Yes, Justice Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Justice Couto and others have appreciated the translation. I can say that one who was really in favour of the Civil Code for Goa, Daman and Diu was Justice Chandrachud. He appreciated the law which existed, especially those three volumes, Marriage, divorce and Law for children, and he said thus: “The Uniform Civil Code remains today a distant world. In my view it would be a retrograde step if Goa, too, were to give up uniformity in its personal laws which it now possesses. Fortunately, as it appears now, the Portuguese followed a different policy in the matter of personal laws than the British. The Civil Code enacted by them covering inter alia family laws applied to all the communities living in this Union Territory except that the customs and usages of non-Christians were saved to a very limited extent. I am quite aware that the Uniform Civil Code of Goa, though it provides an ideal for the rest of the country, creates problems for the Union Territory of Goa itself. The special family laws operating in Goa which are different from those which operate in the rest of the country give rise to the peculiar inter-state conflicts of law. But this did not despair us because inter-state conflict of laws is one of the most perplexing aspects of American Federalism. The conflicts could be minimized by bringing the Portuguese Civil Code in line with some of the central statutes on the subject, at least in basic matters.”

ON: The Constitution of India states that the Civil Code ought to be introduced in India… You have been the Additional Solicitor-General of India. Do you think that the present social climate is favourable, and there have been efforts in that direction, or does the directive remain merely in the pages of the Constitution?

MU: Frankly speaking, till today no steps have been taken. It is an embarrassment to note that even after sixty years nothing has been done. However, the outcome of the Portuguese law was considered when there was a conference between Portugal and Goa, and judges and professors from different universities came here, and everybody spoke and appreciated the existence of the Civil Code. The conference took place when I was the Additional Solicitor-General of India.

ON: Oh! So, it was a very special event and an important step!

MU: After Independence or Liberation, as they call it, Parliament enacted a law, and it was mentioned that all the laws which are maintained are Indian laws. That was thus the first step for the maintenance of those laws – they could be repealed later, but fortunately till today the laws on marriage, divorce and [laws for] children have not been altered by the state. I have to say that there were efforts to discard it but what mattered was what the then Chief Justice of India Justice Chandrachud said: “It is heartening to find out that the dream of the Uniform Civil Code in the country finds its realization in the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. How many outside are aware of this I cannot guess.”

DREAM

ON: Senhor Doutor, one last question: we have seen that the Civil Code is a legacy of the Portuguese. For your part, the translation of the Code is your legacy to the Indian Union.

MU: Yes, exactly. For as long as I live, it is my obligation to work to ensure that it shall continue.

ON: You were speaking of your dream: when would your dream be fulfilled?!

MU: My dream has three facets: first, the marriage must be compulsorily registered before the Civil Registrar, and this gives protection to the family. In the rest of India, this is done before the Hindu priest (Bhat), but it does not serve any purpose. Second, the regime of communion of properties, too, does not exist in the rest of India, and the third: reservation of the disposable share of legitimes is a system which maintains the balance, because half-share is reserved for the family and other half can be disposed of by the testator to whosoever he or she wants.

By introducing the legislation which is in force in Goa, Daman and Diu, justice can be done to all, and the interests of the children and wife can be protected. The concept of moiety which exists as per Portuguese law is recognized under section 5A of the Income Tax Act. This law is maintained by the Indian Union, and the payment of Income Tax by Goans is made, with due regard to the regime of communion of assets, as contemplated by the Portuguese Civil Code.

ON: But it seems that during the last two or three years there have been some problems in this respect.

MU: What problems?

ON: The Income Tax officers do not accept this concept of division of assets.

MU: It is not permissible to ignore the legislation; in fact, it is a violation of the law.

ON: They say that one cannot make a special provision only for Goa...

MU: They cannot be fail to comply with section 5A of the Income Tax Act. In fact, one of the Income Tax officers appreciated it and his subordinates did not want to accept it. He said thus: “If you do not accept, I will insist on making it applicable for the whole of India.”

ON: This brings us to our last question: the beautiful dream you have for India, when do you think it will come true?

MU: I do not know, but, frankly, I am trying to see that my dream is fulfilled. I will continue working till the end.

ON: Senhor Doutor, let me take leave of you, wishing you good health and many more years of work in this field. Thank you very much.

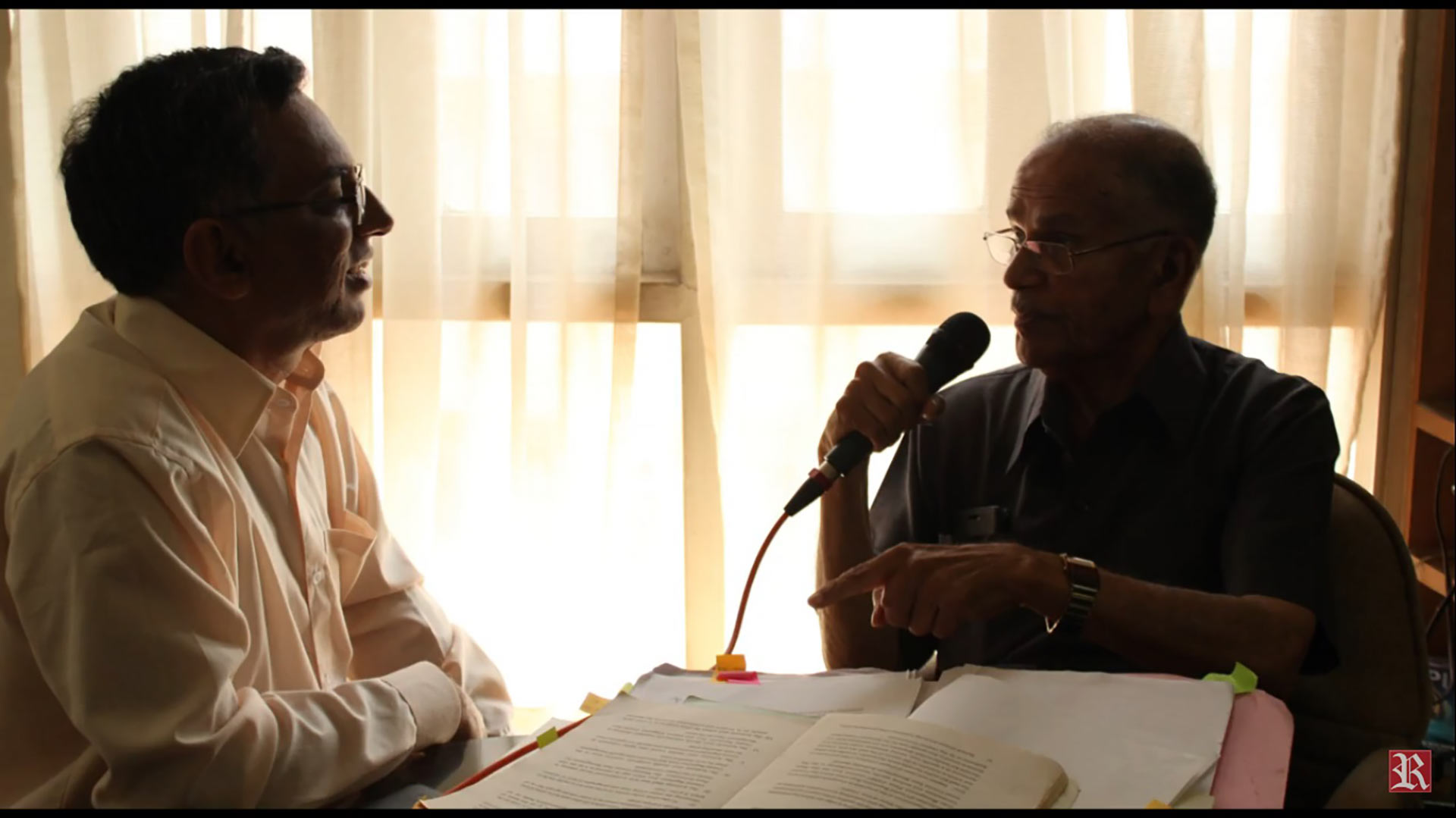

Acknowledgement:

(1) For original chat in Portuguese, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i62XuPeTQuc (2) Translated by Tolentino António Colaço (3) Chat show photographs by Emmanuel de Noronha (4) First published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 13, Nov-Dec 2021, https://casadegoaorg.files.wordpress.com/2022/01/revista-da-casa-de-goa-ii-serie-n13-novembro-dezembro-de-2021.pdf

State Control of Church Property: Unwarranted, Perilous and Counter-Productive

The proposal for State control of Church property has been under discussion, for the last month or so, alas, without any well-defined parameters. The saving grace is that this is a ‘private member’s bill’, so to say, thrown into the public space, and not a State-sponsored debate. Nonetheless, it would be worthwhile to examine some of the disquieting aspects of the subject per se, with particular reference to the proceedings of the seminar on the topic “Should there be a law to protect the properties of the Church?” which was held at the Goa International Centre on 28th July 2009.

Why now? – Precisely what has prompted this debate on State control of Church property in Goa is a mystery. At the said seminar, broad remarks and vague allegations were made about the functioning of the Church; there were some sweeping generalizations, too, mainly because the speakers failed to distinguish between the situation of the Church in Goa and the rest of India. As a result, none of them were able to convincingly state what is wrong with the status quo. If at all the present law regulating relations between the Church in Goa and the State is violative of the law of the land, as it was made out to be, how has the law been in operation for almost five decades? The fact of the matter is that the impugned law is not violative, because Ordinance No. 2 of 1962, promulgated by the President of India, provided for the continuance of that law and many others.

The theme of the seminar was artfully worded. It gave one the impression that the Church had solicited help and so the State was going to privilege her with a law protecting her properties from whosoever. While this was only too good to be true, it was also unnecessary, because the Church today is not seeking privileges any more than she rightfully has; what she eagerly desires, however, is conditions conducive to working peacefully within a secular framework.

Is ‘Secularism’ pliable? – Secularism would ideally mean total separation of Religion and the State, leaving no room for the latter’s intervention in the affairs of religious bodies. In a free society the State has to refrain from interfering with matters of a religious nature; its duty is to ensure that individuals can freely profess, practise and propagate their religion. In India, these rights can theoretically be abridged on grounds of public order, morality or health; the State can even make a law regulating or restricting any economic, financial, political or other secular activity associated with religious practice. But all this has to stand the test of “reasonable restrictions”, and it is incumbent upon the State to prove the need for change, lest the idea of secularism should turn pliable to the State’s whims and fancies.

Perils of State Intervention – One may tend to believe that State intervention is ‘safe’, considering that the rights of the minorities and the freedom of religion stand guaranteed by the Indian Constitution. One may not even feel threatened by some initial State involvement strictly limited to the secular part of a religious matter (say, the scale of expenses to be incurred by a religious institution in connection with rites and observances). In practice, however, such intervention can be an irritant or worse, an intrusion in the religious affairs of a body. Hence it must be ensured that the State intervenes only in extremis.

At any rate, is the Church in Goa a fit case for State intervention? And whatever the modalities of control sought to be exercised on the Church in Goa, citizens would, in the first place, doubt the State’s credentials for such a task! This is not to question the sovereignty of the State but only to emphasize that the State has almost always been a poor manager. For instance, by its intervention, a centuries-old, home-grown and much loved institution like the Ganvkari or Comunidades is in a shambles today. Such is the track record of the State that one can foresee that its control on Church property could result in gross mismanagement, appropriation of funds, encroachments, sale and alienation of lands, and the dismantling of the Church infrastructure, leading to a gradual demolition of the religion.

Political and administrative interference from the State is something that Boards and Trusts of some religious communities outside Goa have often complained about. Some faith communities were compelled by the civil law to have State-managed bodies appointed to run their affairs, because of certain circumstances related to the pre- and post-Independence history of their respective faiths. For them, State intervention became a necessary evil, whereas in Goa history took a different course. Therefore the argument that all religions, everywhere in India, must be on the same footing – or, in other words, suffer from the same malaise – is simply not tenable!

State within a State? – It was pointed out with gusto at the seminar that there cannot be a State within a State. Fair enough. But why cast a slur on the Church in Goa? Has the Church thrown a challenge or posed a threat to the secular State?

The ‘State within the State’ syndrome is perhaps true of some of our business houses. How else does one explain the lingering case of the decrepit River Princess? The concerned business house rules the waves, suggesting that they never will be slaves (with due apologies to ‘Rule Britannia!’). Indeed, they are a State within the State!

Or is it simply the magnitude of the Church’s holdings that makes her look like a State within a State? If yes, let this yardstick apply to our mineral ore exporters; they have to be held accountable for creating environmental problems – and what is more – while making profits on what is essentially State property! Will there ever be the political will to intervene in the internal affairs of these erring business houses?

In contrast, Church assets, mainly comprising donations and gifts from members of the community, have several onuses to be fulfilled. They are held by specific Trusts and their proceeds employed for charitable purposes, particularly education and health among the poorest sections and across faith communities.

Finally, is it the influence that the Church wields in public life that makes her look like a State within a State? Then the same objection should logically extend to the whole of the Fourth Estate!

And at this rate, we shall soon cease to be a democratic State!

Has the Church been above the law? – The world over, the internal affairs of the Catholic Church are governed by the Canon Law. Thanks to her international juridical personality, the said law is admissible in the court of law, since it is not at variance with the civil law. Hence the question “Can you allow any religious head to exercise his power without any regulation?” is malicious, and offensive to the head of the Church in Goa. While observing that “any activity ungoverned by law is lawlessness and would lead to arbitrariness” the speaker failed to recognize that India suffers miserably from lawlessness and arbitrariness despite a proliferation of civil and criminal laws (or sometimes because of it)!

So was it right to peremptorily accuse the Church of ‘lawlessness’? As an institution she enjoys a centuries-old tradition of respecting the canon, civil and criminal laws, and this has naturally made her members law-abiding citizens of the country and the world.

Unique Goan Situation – A look at the situation in Goa as a former Portuguese colony should provide answers to many a nagging question. It is well known that in 1961, in support of the many solemn promises that had been made earlier with regard to preserving Goa’s identity, many Portuguese laws were accepted by the Republic of India – for instance, the Portuguese Civil Code, now hailed by all communities in Goa as being fair and progressive and by the Union of India as a model for the country.

Now this has privileged the Hindu, Catholic and Muslim communities in Goa vis-à-vis their pan-Indian counterparts. And it is within this historical framework that their institutions have been functioning, be it the Confrarias, Fábricas and Cofres of the Catholics or the Mazanias of the Hindus. Now, should all these institutions that are unique to Goa change only because they do not conform to a pan-Indian model? If so, where is the principle of Unity in Diversity?

Therefore, the contention that the existing law in Goa regulating the relations between the Church and the State should be modified for the same reasons and to the same extent as it was modified in Portugal, as authoritatively stated at the said seminar, is unacceptable. Are we still tied to the apron strings of Portugal (the proverbial ‘colonial hang-over’) or conveniently blind to the fact that the Goan/Indian Christian situation is different from the Portuguese?

Transparency and Accountability – This is of the essence. The Catholic Church in Goa is equipped from within to ensure the same in temporal matters, the General Statutes of Confraternities and Rules and Regulations of Fábricas & Cofres being two main examples. There is an ever-increasing participation of both the clergy and the laity in all her institutions, which amounts to an internal system of checks and balances. There is a well-established hierarchy to oversee the same. Besides, the Church is subject to all the laws of the land, including the agrarian reform; her accounts are audited, like those of any other civil body, and she pays taxes to the State without any special exemptions. This time-tested organization has found acceptance the world over; so why all this nitpicking here?

Therefore, to allege (on behalf of the State) that the assets of the Church are being mishandled is a classic example of the pot calling the kettle black! Can the State legitimately claim that it utilizes public assets in a responsible manner? Isn’t mismanagement or embezzlement of funds the order of the day in the State? If stray occurrences of this nature inside the Church can justify State intervention, then the reports of chaotic happenings in the country surely call for declaration of a state of emergency!

The Church fulfils her legal duty of rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s; she renders what is due, nothing less – so why should the State demand anything more?

First published in Renovação (Vol. XXXVIII, No. 17, 1-15 Sept 2009, pp 7-8) under the title 'State Control on Church Property: Unwarranted, Perilous and Counter-Productive'. Reprinted with permission by The Navhind Times (20 Sept 2009) as 'Church Knows Best', in 'Panorama', Sunday magazine, p. 1.