Desdobrando Goa | Unfolding Goa

Editorial

https://online.fliphtml5.com/bcbho/hzql/#p=1

A nossa minúscula Goa tem o condão de se desdobrar em diversas Goas. Existe a Goa da história e a da contemporaneidade, a Goa geográfica e a dos corações espalhados pelo mundo, a Goa real e a dos nossos sonhos. Há, portanto, diversas Goas. E dentro de cada uma existem engrenagens sociais, económicas, políticas e culturais, sempre a rodar. Quem imagina conhecer as múltiplas Goas vive a fábula indiana dos Cegos e o Elefante.

Todavia, a Revista da Casa de Goa empenha-se por interpretar essas Goas aos leitores. É o caso da presente edição, que começa por falar de Pangim, a poética capital goesa, que dantes teve outros nomes: Nova Goa e Cidade de Goa. O nosso editor associado José Filipe Monteiro conta a interessante história de como, no século XIX, esse modesto bairro da aldeia de Taleigão passou à capital do império português oriental.

Por mera coincidência, outro editor associado, Valentino Viegas, recorda na sua crónica os “doces anos” que viveu em Pangim e em calções percorreu os seus cantos e recantos. E, que maravilha, ficarem de repente, lado a lado, a grande e a pequena história da Índia Portuguesa.

Não é, porém, maravilha a situação que de momento se vive em Goa. Leia-se o artigo intitulado “Será Goa a próxima Ayodhya na Índia?”, de Ivo de Noronha. Goa, aliás, destacada pelo modelo de coexistência pacífica que representa entre as diversas comunidades e pelo seu forte senso de identidade cívica, enfrenta hoje um desafio tão subtil quão insidioso.

Em situações dessas, é tão reconfortante lembrar, como o faz David Pinto, no seu artigo “Globalização em Goa: a contradição asiática”, que essa mesma Goa foi na verdade uma das primeiras sociedades multiculturais e globais de todos os tempos. Acrescenta que, ainda no século XXI, viver em Goa “proporciona uma experiência diferente da de qualquer outra parte da Índia”.

Nota-se esse tipo de pioneirismo na recente nomeação papal do padre jesuíta Richard Anthony D’Souza como Director do Observatório do Vaticano. Prova de como um goês naturalmente se torna cidadão do mundo. Na secção de notícias, damos pormenores dessa honrosa atribuição.

É afinal a sua cultura multissecular que define Goa. Veja-se o caso de Manohar Rai SarDessai, cujo “papel cultural híbrido, ao navegar pelas complexidades da identidade pós-colonial em Goa” é objecto de estudo de Anthony Gomes, no artigo intitulado “Vozes da identidade goesa”. O autor refere-se à literatura mundial que o poeta traduziu para concani; o seu papel no enriquecimento da paisagem literária regional, na promoção do diálogo cultural e na articulação da identidade cultural goesa.

Por sua vez, Júlia Serra foca outro poeta contemporâneo, José Rangel, que reuniu parte da sua obra em Toada da Vida e Outros Poemas. Os seus poemas são de índole diversa: para além do misticismo religioso do Oriente e do dinamismo do Ocidente, há referências a línguas, à procura da identidade, à cultura, à paisagem confrontada com o arranha-céus, à vida nos cabarets; e reflexões sobre o bem e a graça divina, sobre o profano e o religioso, e sobre o amor cantado nas diversas dimensões.

Recuando um pouco, Philomena e Gilbert Lawrence evocam a figura de Luís Vaz de Camões, que em Goa escreveu grande parte d’Os Lusíadas; e traçam paralelos com a vida do eminente Winston Spencer Churchill: foram ambos militares de duas potências coloniais na Ásia.

Ainda hoje continua esse diálogo intercivilizacional iniciado há cinco séculos. Por exemplo, a Fundação Oriente desempenha uma vasta rede de actividades, registadas aqui por Paulo Gomes, seu Delegado em Goa, a oriental Lisboa.

Por outro lado, neste mês, na capital portuguesa, realiza-se LisGoa, um encontro de líderes empresariais de Goa, como destacado no suplemento especial a esta edição.

Não termina ali a panorâmica histórica e cultural de Goa. O conto em concani, ambientado no remoto concelho de Satari, transporta-nos para uma Goa de outrora, dir-se-ia, pré-portuguesa, pois distam muito os costumes desse povo, daqueles que são correntes nas partes cristianizadas de território. “A Árvore de Fruto Amargo”, de Prakash Parienkar, transliterado do concani em caracteres devanagáricos para romanos e traduzido para português pelo editor associado Óscar de Noronha, vai acompanhado também do link do respectivo filme.

Rematamos a apresentação desta edição convidando os leitores à nossa secção de arte. Girish Gujar e Govit Morajkar, respectivamente, em aguarela e pintura, chamam a nossa atenção a dois locais em Goa; o caricaturista Alexyz tece uma crítica aos problemas de Goa contemporânea, enquanto Clarice Vaz e Edgar João apresentam Goa como o eterno idílio.

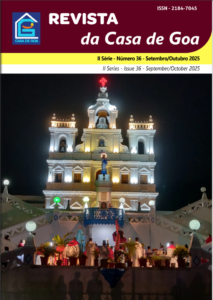

E não vamos sem registar que na capa desta edição temos a Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Imaculada Conceição, o ex-libris da cidade de Pangim; e na contracapa, o link da Global Goan, nossa Revista parceira, cuja leitura calorosamente recomendamos aos Goanófilos.

-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-

Our minuscule Goa has the power to unfold into several Goas. There is the Goa of history and the Goa of contemporary times, the geographical Goa and the Goa of hearts scattered around the world, the real Goa and the Goa of our dreams. There are, therefore, several Goas. And within each of them are social, economic, political and cultural gears that continue to turn. Those who claim to know them all live out the Indian fable of the Blind Men and the Elephant.

Nonetheless, Revista da Casa de Goa strives to interpret these Goas for its readers. The present edition is a case in point. It begins by talking about Panjim, the poetic capital of Goa, which previously had other names: New Goa and City of Goa. Our associate editor José Filipe Monteiro recounts the interesting story of how in the nineteenth century this modest ward of the village of Taleigão grew into the capital of the Portuguese Oriental empire.

Coincidentally, another associate editor, Valentino Viegas, recalls in his column the “sweet years” he spent in Panjim, and in shorts explored its nooks and crannies. And, how wonderful to suddenly see, side by side, the macro and the micro history of Portuguese India.

However, the living situation in Goa is not all that wonderful. Read the article titled ‘Will Goa be India’s next Ayodhya?’, by Ivo de Noronha. In fact, although known as a model of peaceful coexistence among different communities, and for its strong sense of civic identity, Goa faces a challenge that is as subtle as it is insidious.

In situations like these, it is so heartening to recall, as David Pinto does in his article ‘Globalisation in Goa: The Asian contradiction’, that Goa was indeed one of the first multicultural and global societies of all times. He adds that, even in the 21st century, living in Goa ‘provides an experience different from that in any other part of India.’

This type of pioneering spirit shines through Jesuit priest Richard Anthony D'Souza’s recent papal appointment as Director of the Vatican Observatory. A Goan quite naturally becomes a citizen of the world. In the news section we have more details of that honourable selection.

After all, it is Goa’s centuries-old culture that defines it. Look at Manohar Rai SarDessai, whose ‘role as a cultural hybrid navigating the complexities of identity in postcolonial Goa’ is the object of study by Anthony Gomes in his article titled ‘Voices of Goan Identity’. The author refers to the poet’s translations of world literature into Konkani and his role in enriching the regional literary landscape, promoting cultural dialogue, and articulating the Goan cultural identity.

Júlia Serra, for her part, focusses on another contemporary poet, José Rangel, who compiled part of his work in Life’s Refrain and Other Poems. His poems are diverse in nature: in addition to the religious mysticism of the East and the dynamism of the West, there are references to languages, the search for identity, culture, the natural landscape vis-à-vis the skyscrapers, life in cabarets; and reflections on goodness and divine grace, on the profane and the religious, and on love sung in its various dimensions.

Rewinding a little, Philomena and Gilbert Lawrence evoke the figure of Luís Vaz de Camões, who wrote a large part of The Lusiads in Goa, and they draw parallels with the life of the eminent Winston Spencer Churchill: both were soldiers of two colonial powers in Asia.

This inter-civilisational dialogue, which began five centuries ago, is still on. For example, the Orient Foundation engages in a wide range of activities, listed here by Paulo Gomes, their delegate in Goa, the oriental Lisboa.

On the other hand, LisGoa, a meeting of business leaders from Goa, is due to be held in the Portuguese capital this month, as highlighted in the special supplement to this edition.

The historical and cultural overview of Goa does not end there. The short story in Konkani, set in the remote taluka of Satari, transports us to a Goa of yesteryear, one might say, pre-Portuguese, as the people’s customs there are very different from those in the Christianised parts of the land. Prakash Parienkar’s ‘The Bitter-Fruit Tree’, transliterated from Konkani in the Devanagari to the Roman script and translated into Portuguese by associate editor Óscar de Noronha, also carries a link to the respective film.

To conclude our presentation of this edition, we draw our readers’ attention to the art section. Girish Gujar and Govit Morajkar, in watercolour and painting, respectively, put the spotlight on two locales in Goa; cartoonist Alexyz critiques issues of contemporary Goa, while Clarice Vaz and Edgar João present Goa as the eternal idyll.

And we cannot resist pointing out that our cover features the Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, Panjim’s most famous landmark; and our back cover has the link to Global Goan, our partner magazine, a must-read for every Goa-phile.

Utopia ou distopia? | Utopia or dystopia?

Editorial

Utopia ou distopia?

Sem que isso tivesse sido planeado, o presente número da nossa Revista lança um olhar crítico sobre o passado e o presente de Goa e abalança-se sobre o seu futuro.

Para começar, chamo à atenção ao ensaio intitulado ‘A história e a utopia da viagem’, em que Júlia Serra, depois de retratar Albuquerque e a sua arrojada viagem ao Oriente no século XV, refere-se a três viajantes modernos – o médico Lúcio Augusto da Silva, o jornalista Ernesto Várzea Jr. e Fernando Laidley, um apaixonado pelos automóveis – para quem a viagem de Lisboa a Goa e além, foi utopia, mas também “espaço-tempo de realidade e vivência pessoal”.

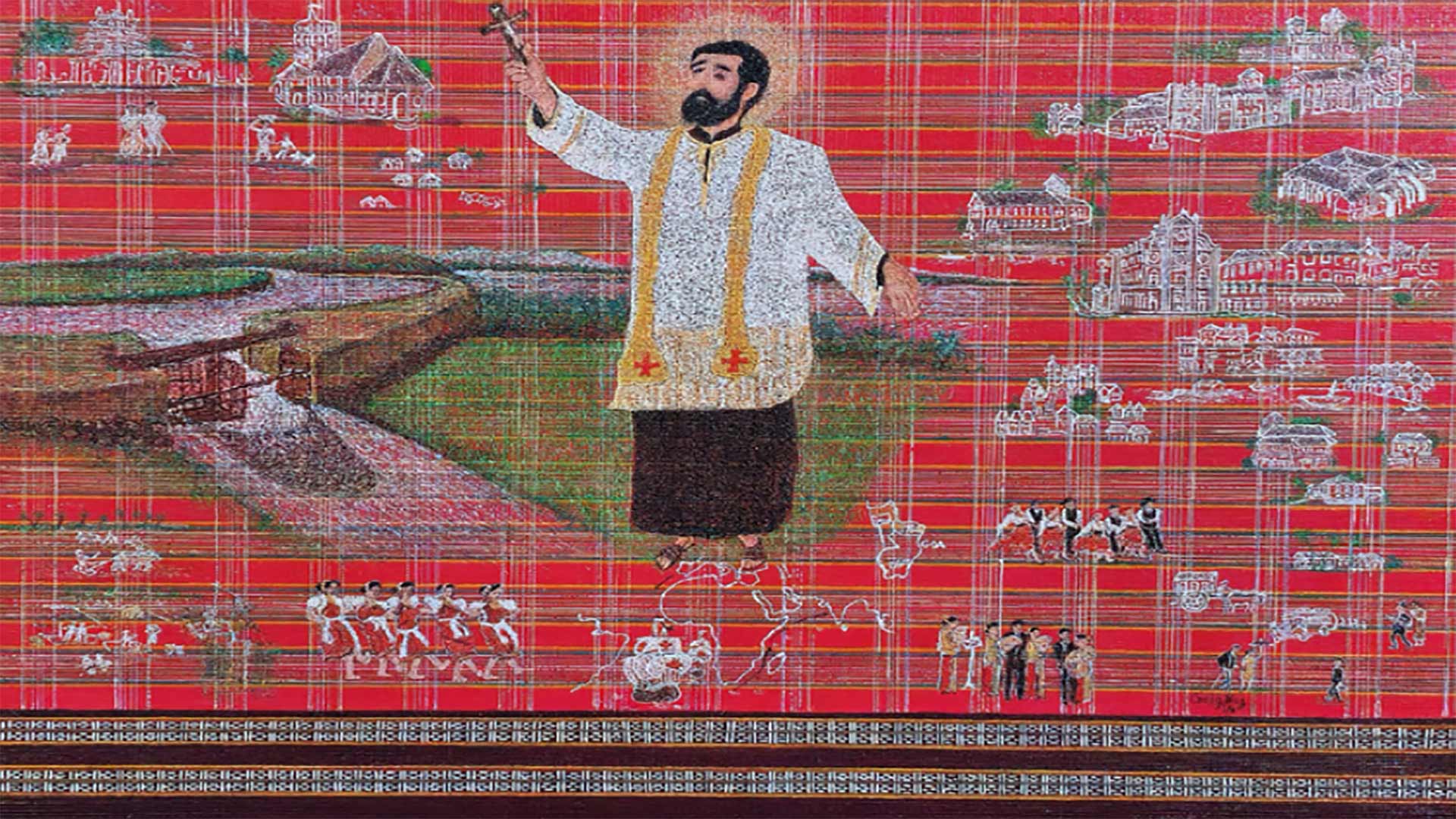

Nesse sentido, a figura máxima de viajante e sonhador, na melhor acepção da palavra, foi, sem dúvida, S. Francisco Xavier. Objecto de reflexão no nosso número anterior, é agora relembrado pelo jesuíta Délio Mendonça, que no seu artigo “Pegadas de Esperança” descreve a galeria de pintura goesa, patente na Velha Cidade de Goa por ocasião da Exposição das Sagradas Relíquias do Santo, na qual “uma caraterística comum marcante destas pinturas é a Goanização e a contextualização de Xavier”.

No âmbito da arte musical, noticiamos o vídeo e o cantar público do icónico hino em concanim, “Sam Fransiscu Xaviera”, recentemente traduzido para português pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

Na mesma esteira, a primeira prestação do ensaio em que é historiado o ‘Colonialismo português na Ásia’, o casal Gilbert e Philomena Lawrence não deixa de se referir ao Santo basco, que ficou “gravemente desiludido com o comportamento dos colonos”. Logo depois deixou Goa para trabalhar em territórios não lusitanos do Sul da Índia, Malásia e Japão.

Vê-se, pois, que Goa foi Utopia para um grande número de pessoas de todos os tempos. De entre os da contemporaneidade, V. M. (Nitant) Kenkre, em poema, recorda-se com saudade de “Goa da minha infância”, enquanto no seu ensaio trata mais especificamente das escolas de português que frequentou.

Nos mesmos moldes, Ralph de Sousa dedica-se ao porto de Mormugão, na segunda prestação da série de ensaios sobre as “Luzes dos portos e delícias marítimas”.

Da pena desse colaborador está em destaque o livro Change of Guard (Render da Guarda), ora em avaliação crítica de Heta Pandit.

Que a relação entre Goa e Portugal foi uma aventura multissecular fica comprovado não só pelas excelentes relações humanas entre os dois povos, como também, em particular, pelo seu roteiro gastronómico. É o caso do chacuti que, nas palavras do nosso editor associado José Filipe Monteiro, é “a iguaria mais genuinamente goesa”; e o qual, no conceito do prestigiado crítico Fernando Melo, está em casamento feliz com Casal da Coelheira Private Collection Alicante Bouschet tinto. Saboreiem-nos!

Tão depressa, como alimento para a mente, apresentamos, no Cantinho do Concani, a décima prestação de Adágios Goeses, selecionados do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, de R. B. Barreto Miranda, e transcritos em concani moderno por Óscar de Noronha.

Como ímpar exemplo humano da sabedoria indo-portuguesa, é focada, pela pena de Mário Viegas, a personalidade polivalente de Indalêncio Froilano Pascoal de Mello.

Seria exagerado afirmar que tudo isso aponta para a Utopia que foi Goa, no decorrer dos tempos?

Por outro lado, temos a situação de Goa na actualidade. Ivo de Noronha, no ensaio intitulado “Empreendimentos de luxo em Goa: bênção ou maldição?”, questiona-se sobre o dinheiro que entra e a identidade que vai desaparecendo com a vaga de construções extravagantes em Goa… Oxalá que não seja isso um reflexo da profecia atribuída a S. Francisco Xavier: “Goa ninguém a levará; por si acabará”!

Noticiamos com um misto de sentimentos que o “Mapeamento da morte da floresta de manguezais” em Goa, fotografada por Payal Kakkar, venceu a medalha de prata no Tokyo International Photo Awards 2024. Congratulamo-nos pelo facto de essa situação ambiental suicida ter sido constatada por uma agência estrangeira.

Outra notícia na respectiva secção é a distinção de Abílio Fernandes com medalha de oiro que lhe foi atribuída pelo município de Évora, apreciando o facto de o centro histórico da cidade-museu ter sido elevado pela UNESCO ao estatuto de Património Mundial da Humanidade durante a presidência autárquica do homenageado há 38 anos.

Enquanto deixa um trilho de esperança a actividade cultural de grande relevância que a Fundação Oriente vem exercendo em Goa, como se vê pelo seu desempenho nos últimos dois meses, é muito aguardada a participação da apreciada fadista Cuca Roseta, no Festival do Monte 2025, que comemora os 30 anos dessa instituição em Goa.

Também as aguarelas de Girish Gujar (“Casa na Ilha de Divar”) e de Taniya Shetke (“Abundância divina”); as pinturas de Edgar João (“Murmúrios da Monção”), João Coutinho (“Mahakavi Camõis”), e Rouella Barreto (“A arte do fenim de caju”) são uma agradável brisa vinda dos mais pitorescos locais de Goa, muito embora a pintura de Chaitali Naik (“Festival dos Ladrões”), para não falar da caricatura (“O que resta para comemorar?”) do octogenário Alexyz, façam nascer um sorriso irónico nos nossos lábios.

No meio de tudo isso, em duas cartas ao director, comenta Júlia Serra, primeiro, sobre a reportagem televisiva intitulada “Goa, Coração Português”, da SIC Notícias, que passou em Portugal em novembro do ano próximo findo: “Goa entra nas casas portuguesas” é como intitula o seu apontamento. E logo depois, escreve sobre “Goa e as tradições portuguesas”, que veio a conhecer, através da Agência Lusa, que divulga a situação da língua e cultura portuguesa, e em particular como é celebrada a quadra natalícia em Goa. Dir-se-ia, por isso, que é o caso de Portugal ter entrado nas casas goesas!

Finalmente, o nosso editor associado Valentino Viegas expõe a prata da casa no relato que faz por ocasião do centésimo número da nossa Revista. E, em carta ao director, chama atenção à operação policial realizada na Praça Martim Moniz, em Lisboa, a qual, segundo diz, pôs em risco, “a bela imagem de Portugal multicultural e multirracial, difundida pelo mundo inteiro, a viver em harmonia, paz e sossego, que tanto nos custou a criar”.

Esperemos que Goa, a Aparant, e Lisboa, a Felicitas Julia – duas Utopias do passado – se mantenham fiéis aos seus gloriosos epítetos, e nunca se tornem distopias.

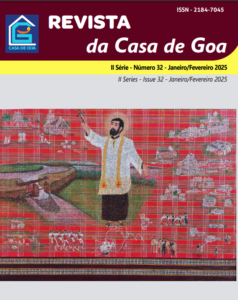

Capa: 'Fios de Goa' (pintura com seringa, acrilico em tela), de Clarice Vaz

Editorial

Utopia or dystopia?

Without any prior planning, the current issue of our magazine has taken a critical look at Goa’s past and present and looks at its future as well.

To start with, I would like to draw your attention to the essay entitled ‘History and the Utopia of Travel’, in which Júlia Serra, after portraying Albuquerque and his daring journey to the East in the 15th century, refers to three modern travellers – physician Lúcio Augusto da Silva; journalist Ernesto Várzea Jr. and car enthusiast Fernando Laidley – for whom the journey from Lisbon to Goa and beyond was a utopia, but also a ‘space-time of reality and personal experience’.

In this sense, St Francis Xavier was undoubtedly the ultimate traveller and dreamer, in the best sense of the word. He was the subject of reflection in our previous issue, and is now remembered by a fellow Jesuit, Délio Mendonça, who in his article ‘Footprints of Hope’ describes the gallery of Goan paintings on display in the Old City of Goa on the occasion of the Exposition of the Sacred Relics of the Saint, and in which ‘a striking common feature of these paintings is the Goanisation and contextualisation of Xavier’.

In the field of music, we report on the video and the public singing of the iconic hymn in Konkani, ‘Sam Fransiscu Xaviera’, recently translated into Portuguese by our associate editor Óscar de Noronha.

In the same vein, the first instalment of the essay on ‘Portugal’s Colonialism in Asia’, by Gilbert and Philomena Lawrence, does not fail to refer to the Basque saint, who was “gravely disappointed by the behaviour of the colonists”. Soon afterwards, he left Goa to work in non-Portuguese territories in South India, Malaysia and Japan.

Apparently, Goa has been Utopia for a large number of people throughout history. In contemporary times, V. M. (Nitant) Kenkre’s poem ‘Goa of my Childhood’ is a nostalgic recollection, while in his essay he deals more specifically with the Portuguese language schools he attended.

Likewise, Ralph de Sousa focuses on Mormugão Port, in the second instalment of a series of essays titled ‘Harbour Lights and Maritime Delights’.

The said writer’s book Change of Guard is critically reviewed here by Heta Pandit.

The fact that the relationship between Goa and Portugal has been an adventure across centuries is proven not only by the excellent human relations that exist between the two peoples, but, in particular, by their gastronomic journey. So is the case of xacuti which, in the words of our associate editor José Filipe Monteiro, is ‘the most genuinely Goan delicacy’; and which, in the prestigious critic Fernando Melo’s view, is happily paired with Casal da Coelheira Private Collection Alicante Bouschet red. Savour them!

Just as quickly, as food for thought, we present, in the Konkani Corner, the tenth instalment of Goan adages, culled from R. B. Barreto Miranda’s book Enfiada de Anexins Goeses and transcribed into modern Konkani by Óscar de Noronha.

As a unique human example of Indo-Portuguese wisdom, Mário Viegas focuses on the versatile personality of Indalêncio Froilano Pascoal de Mello.

Would it then be an exaggeration to say that all of this points to the Utopia that was Goa down the ages?

On the other hand, we have Goa’s situation today. Ivo de Noronha, in his essay titled ‘Luxury developments in Goa: a boon or a curse?’ wonders about the money being earned and the identity being lost with the wave of extravagant constructions in Goa... Let’s hope that this isn’t a telltale sign of a prophecy attributed to St Francis Xavier: “None will take away Goa; it will end by itself”!

We announce with mixed feelings that ‘Mapping the death of mangrove forest’ in Goa, photographed by Payal Kakkar, was awarded a silver medal at the Tokyo International Photo Awards 2024. We are pleased to note that the said suicidal environmental situation has been acknowledged by a foreign agency.

Another news item in the respective section is the municipality of Évora’s award of a gold medal to Abílio Fernandes, in appreciation of the fact that UNESCO elevated the historic museum-city to World Heritage status during his mayorship, thirty-eight years ago.

While the hugely relevant cultural activity that Fundação Oriente has been carrying out in Goa, as seen from its report of the last two months, leaves a trail of hope, the presence of the acclaimed fado singer Cuca Roseta in the forthcoming Monte Festival, on the 30th anniversary of the Foundation’s Goa Delegation, is something to look forward to.

Watercolours by Girish Gujar (‘House on the Island of Divar’) and Taniya Shetke (‘Divine Abundance’); paintings by Edgar João (‘Monsoon Murmurs’), João Coutinho (‘Mahakavi Camõis’), and Rouella Barreto (‘The Art of Cashew Feni’) are like a pleasant breeze from Goa’s most picturesque locations, even while Chaitali Naik’s painting (‘Festival of Thieves’), not to mention octogenarian Alexyz’s cartoon (‘What is left to celebrate?’), bring an ironic smile to our lips.

In the midst of it all, by way of two letters to the director, Júlia Serra comments, firstly, on SIC Notícias’ TV report titled ‘Goa, Coração Português’ (Goa, a Portuguese Heart), which aired in Portugal in November last year: ‘Goa enters Portuguese homes’ is how she titles her note. Soon thereafter she writes about ‘Goa and Portuguese traditions’, which she learnt about from Lusa News Agency’s report on the status of Portuguese language and culture, and in particular the celebration of Christmas in Goa. One may note, conversely, that Portugal has entered Goan homes!

Finally, our associate editor Valentino Viegas showcases the family silver in his piece marking the 100th issue of our magazine. And in a letter to the director, he draws attention to the police operation that happened in Lisbon’s Martim Moniz Square, which, he says, jeopardized ‘the beautiful image of multicultural and multiracial Portugal, spread across the world and living in harmony, peace and quiet, all of which we have worked so hard to create’.

Let’s hope that Goa, the Aparant, and Lisbon, the Felicitas Julia – two Utopias of the past – remain true to their glorious epithets and never turn into dystopias.

Cover: 'Goan Threads' (syringe painting, acrylic on canvas), by Clarice Vaz