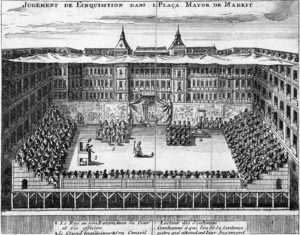

What was the Inquisition? – 1

The Inquisition has long been made to look monstrous. The Essential Catholic Survival Guide reckons that “to non-Catholics it is a scandal; to Catholics, an embarrassment; to both, a confusion.” Indeed, our generation shies away from its memory or, if caught on the back foot, quickly turns apologetic. It is as though we are under a spell, and this is the handiwork of those inimical to the Catholic Church or at least unaware of the real functioning of the court that was the Inquisition.

The point here is not to whitewash a much maligned institution but to understand its nature. We are before a formal tribunal, not a mere people’s court; that this court had well established procedures, similar to modern courts in many ways and, obviously, following contemporaneous standards of justice, however alien they may seem to our generation. And given the lack of documentation, it is unreasonable to depend on statistics alone to make up our minds about that institution.

Definitions

‘Inquisition’ and ‘Heresy’ are two terms that call for special attention. The first one, from the Latin inquirere, meaning “to inquire”, refers to questioning. Roman law provided for an inquisitorial procedure by magistrates investigating crimes in the absence of formal charges being brought to their attention. After the Empire converted to Christianity in the fourth century, the procedure was employed by emperors from Constantine onwards to investigate heresy and related cases. It behoved the State to uproot this crime which always had socio-political implications; it was only in the second millennium that the Pope intervened, to rein in excesses, by setting up a formal tribunal, though not fully successfully.

Heresy isn’t the same thing as incredulity, schism, apostasy or some such sin against the faith. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines heresy as “the obstinate post-baptismal denial of some truth that must be believed with divine and Catholic faith; or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same.” The doubt or denial involved in heresy concerns a matter that has been revealed by God and solemnly defined by the Church, be it the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation, the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, Papal Infallibility, the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary.

It was the task of the Inquisition to ascertain whether a person was guilty of propagating a heresy. Mere holding of wrong notions of Catholic doctrine privately did not attract sanctions from the court. Only a person found to be spreading those views came under the scanner of the Inquisition; and only refusing to be corrected would be considered heretics.

The Inquisition judged Christians; it was thus no torture plan to convert people to Christianity, as it is made out to be. Neither was it an instrument of evangelisation nor were there ever any provisions under Church law for the use of force to convert a person to the faith. The Inquisition aimed primarily to try and reform the accused and win them back to the faith. However, as heresy was an offence under the law, the tribunal, like a parent punishing an intractable child, would have hardened offenders penalised, so as to safeguard the common good. In those days, when Church and State were united, like soul and body, the law holistically catered to the citizens’ spiritual and material welfare. It goes without saying that very often the State overruled the Church, disparaging the spiritual and reformatory aspect and exalting the material and punitive side.

Historical development

Like Moses who was anguished by his people’s worship of the Golden Calf, the Christian Apostles too were deeply concerned about guarding and transmitting the deposit of the Faith undefiled. Unfortunately, not only the early days of Christianity, the whole of the first millennium was riddled with heretical doctrines: the Circumcision heresy (1st c.); Gnosticism (1st-2nd cs.); Montanism (late 2nd c.); Sabellianism (early 3rd c.); Arianism (4th c.); Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism (5th c.); Nestorianism (5th c.); Monophysitism (5th c.); Iconoclasm (7th-8th cs.) and Catharism (11th c.). The Church authorities suffered the consequences of those heresies but, rather than opting for the Old Covenant penalties of death or scourging, simply excommunicated the heretic.

On the other hand, the imperial successors of Constantine, who regarded themselves as masters of the temporal and material conditions of the Church, were persuaded that it was their first concern to protect the State religion. Heresies generated anarchy, so penal edicts (confiscation of property and death) were issued regularly against heretics. A law of the year 407 asserts for the first time that heresies ought to be equated with high treason. For their part, the church authorities in the Christianised states of the Roman Empire refused to invoke the civil power against the heretics.

Ironically, it was the heretics who appealed to the civil power for protection against the Church, and before long complained bitterly of administrative cruelty. At this point, Bishop St Optatus of Mileve defended the civil authority, thus championing for the first time a decisive cooperation of the State in religious questions and its right to inflict death on heretics. This matter wasn’t settled unequivocally given that several ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel. St Augustine was one such bishop who tried to lead back the erring by means of instruction. However, he changed his views, perhaps moved by the incredible excesses perpetrated by the heretics. Yet, it was the desire of the bishop of Hippo to correct them, not put them to death; he wanted the triumph of ecclesiastical discipline, not the death penalties that they deserved.

Meanwhile, as often as the social welfare required it, Christian rulers sought to stem the evil with appropriate measures. In an attempt to save the kingdom and save souls, even distinguished citizens, ecclesiastical and lay, were burnt at the stake. Often there were outbursts of Christian popular sentiment against dangerous sectaries. Sometimes the people blamed the clerical softness in pursuing heretics and so took the law into their hands. Kings and bishops responded by condemning heretics to the stake to prevent the spread of what they called “the heretical leprosy”.

According to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, a definitive strategy came about after Frederick Barbarossa, the powerful king of Germany and Sicily, and Pope Alexander III reached an accord reconciling their respective powers in the Peace of Venice in 1177. This was reaffirmed at the Lateran Council of 1179. In 1184, Pope Lucius III issued the decretal Ad abolendam (‘To abolish diverse malignant heresies’) which some have called the “founding charter of the Inquisition”. It commanded bishops to take an active role in identifying and prosecuting heresy in their jurisdictions. Heretics would suffer excommunication from the Church and be handed over to the civil power to be punished according to the provisions of the common law.

Accordingly, the first Inquisition tribunal was established in southern France in 1184. While death was still not on the cards, punishment was limited to exile, expropriation, destruction of the culprits dwelling, infamy, debarment from public office, and the like. The explicit identification of heresy with treason and its prosecution according to the norms of Roman law was formalised in 1199 by Pope Innocent III. At the Lateran Council of 1215, a relative service was done to the heretics by the introduction of regular canonical procedure to abrogate the arbitrariness, passion and injustice of the civil courts and from the penal codes in Spain, France and Germany.

New Challenges

Although medieval Europe was a society of Catholic kingdoms, adherents of other religions, particularly Judaism and Islam, also lived there. In the first few decades of the thirteenth century, Christian Europe was so endangered by heresy that a formal ecclesiastical tribunal under direct papal jurisdiction became a social, religious and political necessity. Pope Gregory IX established the so-called Monastic Inquisition by his Bulls of 13, 20, and 22 April 1233, appointing Dominican monks as the official inquisitors for all dioceses of France. The Inquisition had jurisdiction only over the Catholic populace; non-Catholics would be hauled up only if found to be perverting Catholic mores. At a time when the people had higher regard for the soul than for the body, heresies were spiritual terrorism to be tackled with vehemence, just as we do against acts of physical violence today.

Broadly speaking, the new tribunals of the Inquisition established in Europe and Asia faced many challenges, some of which are listed below:

a) Catharism (13th century)

These sects were a social menace right from the Byzantine period. They were treated with severity, yet they poured over all of Western Europe. A mix of religions reworked with Christian terminology, Catharism was an umbrella for multiple sects, one of the largest being the Albigensians. By and large, they were not only hostile to the Mass, the sacraments, the ecclesiastical hierarchy and organization, and to the government; their views were fatal to the continuance of human society as they forbade marriage and made a duty of suicide. It was only natural that both Christian and non-Christian custodians of the existing order in Europe should adopt repressive measures against their aberrant teachings.

b) Conversos (15th century)

Pope Sixtus IV empowered Ferdinand and Isabella to set up the Inquisition in Spain in the year 1478, to confront the conversos, pseudo-converts from Judaism (Marranos) and from Islam (Mouriscos). The tribunal turned very fierce even by the standards of the time, so much so that the Pope made efforts to limit the powers of the inquisitors but to hardly any avail. In 1483, a Grand Inquisitor and Supreme Council was appointed to supervise local inquisitorial tribunals, including the later ones in Mexico and Peru. The first Grand Inquisitor, the Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, also exceeded his powers.

c) Protestantism (16th century)

At the turn of the sixteenth century, Europe found itself divided into two ideological blocs: one Catholic and obedient to the Pope; the other, Protestant and opposed to the Pope. After Luther, Calvin and Henry VIII parted ways with the Catholic Church, each began spreading theological ideas that were in conflict with the teachings of the Catholic Church. Their movements began to gain ground in various principalities and kingdoms of northern Europe.

The great apostasy or disaffiliation from the Catholic Church prompted Pope Paul III to establish the Sacra Congregatio Romanae et Universalis Inquisitionis seu Sancti Officii (Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, or the Holy Office), in 1542. It consisted of a commission of six cardinals. They were at once the final court of appeal for trials concerning the Faith and the court of first instance for cases reserved to the Pope. It inaugurated an era of institutionalised inquisitions. Succeeding popes made further provisions for the procedure and competency of the Inquisition of which Pope Sixtus V is regarded as the reorganizer.

In that same year, the Pope made known the first list of books prohibited for their doctrinal content or criticism of the Catholic Church. A more comprehensive Index of Prohibited Authors and Books was brought out after the Council of Trent (1545-63). Later, a separate though related Congregation of the Index updated the list.

d) Paganism (16th century onwards)

This is an umbrella term for beliefs held by polytheistic religions. It applied especially to the religious beliefs of the natives of the colonies held by Portugal and Spain in Asia, Africa and Latin America. King João III of Portugal applied to the Pope for an independent Portuguese Inquisition to deal specifically with threats posed by crypto-Jews in his country. A branch of the tribunal was set up in the city of Goa in 1560 to handle cases relating to the ethnic Portuguese in India and to neo-converts to Catholicism (Jews, Hindus and Muslims) relapsing into their former religions or practising them side by side with Catholicism.

e) Heterodoxy (18th century onwards)

This refers to views that differ from right belief or purity of the Faith, or say, orthodox views. ‘Right belief’ is not subjective, as resting on personal knowledge and convictions, but that which is in accordance with the teaching and direction of an absolute extrinsic authority.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Heterodoxy goes back to Protestant thought in Germany where attempts were made to support by reason the supernatural truths contained in the Holy Bible. In reality such experiments tended strongly in favour of Naturalism, which they had wished to condemn. Heterodox tendencies by so-called free thinkers or dissenters hacked at the sacred obligation of preserving the deposit of Revelation pure and undefiled. The most revolutionary in this regard were the French Encyclopaedists and others of their ilk in Europe and America.

Eventually, Rationalism, or the use of human reason or understanding as the sole source and final test of all truth, began to form the basis of intellectual and scientific activity. It seemed to hold out a promise of dramatic improvement in human life. These tendencies finally led towards religious disbelief, evident in such modes of thought as atheism, agnosticism, materialism, naturalism, pantheism, scepticism, and the like.

New Winds

In the first half of the nineteenth century, the stage was set for republican revolts against European monarchies, beginning in Sicily and spreading to France, Germany, Italy, and the Austrian Empire. They ended in failure, repression and widespread disillusionment among liberals.

Nonetheless, winds of liberalism kept blowing hard, unsettling the traditional ways of thinking. Reason continued to score points against faith and displace it across Europe. In fact, religious beliefs began to be equated with blind faith; so faith looked weird when juxtaposed with free private judgement. The view that orthodoxy should be maintained at all cost began to be looked upon with suspicion.

With religion itself relegated to the background, how could a mere institution that stood staunchly for preserving the deposit of the Faith be welcome? Here was a propitious moment for dissenters to quickly and impudently go about their business of discrediting the Catholic Church. The process that had started with the Protestant Revolution gained steam with the French Revolution. It is no wonder, then, that we moderns experience difficulty in grasping the rationale of the Inquisition. The punishments meted out by the tribunal for heresy seem exaggerated, not to say irrational and misplaced.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

The Inquisition tribunals worked intermittently in the eighteenth century until they were disbanded by the liberal or revolutionary governments of several European countries in the nineteenth century. The Roman Inquisition also came to a gradual end. In 1908, Pope Pius X renamed it Congregation of the Holy Office. A few years later its duties were merged with those of the Congregation of the Index. In 1965, Pope Paul VI reorganized the Holy Office, changing its name to the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and eliminated the Index in the following year.

How are we to explain the Inquisition in the light of its own period? To do justice to the topic, we need to first have a look at the broad features of the tribunal of the Inquisition.

(To be continued… Part 2)

A Wobbly Webinar on the Goa Inquisition

A few hours ago I watched a webinar on the Goa Inquisition, subtitled “untold atrocities by St Francis Xavier and missionaries”. It was flawed from the very beginning, for although St Francis Xavier had wanted the tribunal to put an end to profligacy in the city of Goa, he died in 1552, eight years before it was established. Nor did the panelists accuse any other missionary, in the course of the ninety-minute long proceedings.

The session began with a demand that the horrors, atrocities, brutalities, cruelties, what have you, of the Goa Inquisition be made known to the world, and a museum established at the earliest. You can be sure the webinar was hardly an academic exercise, not just because three out of the four speakers there are politically affiliated, but because the so-called “online exhibition” was exhibitionist, marked by cheap rhetoric and wild exaggeration.

The only academic present on the panel quickly rattled off dates. His only argument was that the Catholics of today are not to be blamed for what happened centuries ago. He should have also brought out the nature of the tribunal; he didn't do so, yet he didn't fail to make some sweeping statements. The professor presented no counter-argument to the macabre theory developed by the organisers of the webinar; but that’s because the other speakers did not put forth any argument in the first place. They were in plain accusation mode; it was all sound and fury, signifying nothing.

When dealing with such a sensitive historical issue, one would expect at least one honest and fair-minded panelist to state the meaning, nature and functions of that much maligned ecclesiastical court of law, and let the listeners make up their minds. On the contrary, the speakers were not only highly critical, they issued summary judgements – something that the very tribunal under attack never did! The tribunal sure had shortcomings but it did follow well laid out procedures and give the accused the right to defend themselves.

Was it that the panelists did not have enough time to go into the main aspects of the Inquisition? Not at all. Going by the organisers’ track record, one would not expect them to give evidence, weigh each word as they spoke, and see both sides of the issue... And how could one expect them to lay their cards on the table? That would in fact have knocked the wind out of their sails. That would have taken the sting out of their agenda.

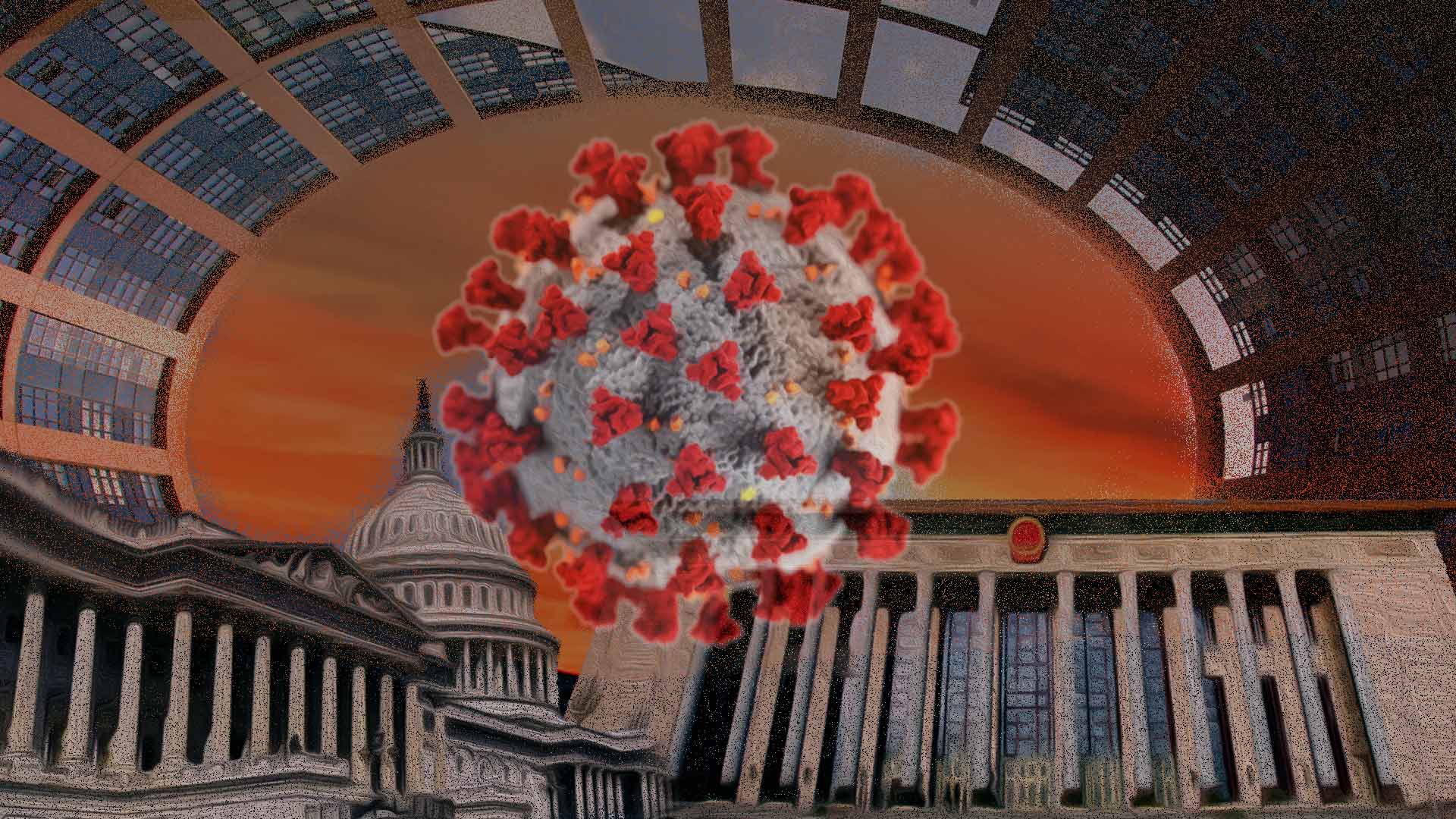

Two Viruses in a Swirl

To say we are living in unusual times is an understatement. Two viruses – the corona and politics – have got our heads in a whirl. On them hinges the health of humanity, the future of humankind. Only a bunch of quick and well thought out policies can now spell the death of the corona. Of course, a lot will depend on what the scientists say and on how well the policy makers warm up to them. A pandemic though it may be, strategies are subject to overall conditions at home. That is why measures to control the infection have varied from country to country; and so have the people’s responses, influenced by opinion makers.

Scientists say that viruses are found in almost every ecosystem on earth. In particular, the coronaviruses constitute a group causing diseases in mammals and birds. In humans, they cause respiratory tract infections ranging from mild (like common cold) to lethal (SARS, MERS and Covid-19). Whereas Coronavirus (Covid-19) is the name of the disease that flared up last year-end, the virus per se is called ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2’ (SARS-CoV-2). WHO refrained from using this label lest it should bring to mind the havoc that the virus created in Asia less than two decades ago.

Mysterious transmission

Ironically, the change of nomenclature ended up being suspect. Many have viewed it as a tactical move to cover up a mysterious case of zoonotic transmission. Soon another theory gained currency: that covid-19 was nothing but a laboratory manipulated virus, which probably leaked ahead of time. Some still believe it was meant to be a bio-weapon. And much though a paper published in Nature Medicine ruled out the possibility of SARS-CoV2 being a “laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus,” the authors conceded quite significantly that “it is currently impossible to prove or disprove the other theories of its origin.”

While China is blamed for spreading the virus, the USA is accused of spreading panic. The two countries have traded insults in a political table tennis or ping pong, but chances are the two extreme political players have met! Many see the American uproar as a ruse to promote their pharmaceutical industry. The logic is that the paranoia will eventually translate into profits; and this is how: even while a vaccine is awaited, deaths will rise – and so will the demand for that elusive preventive. And partners in crime the two countries will be if found pre-engaged in devising a vaccine for the pandemic. Covid-19 would then rightfully be a ‘US-China Virus’!

Be that as it may, acts of commission and omission have kicked off an infamous ‘Covid Era’. The statistics may be doctored but the virus is seen as a killer that came from nowhere; hence the hype, with contentious lockdowns and economic disruptions for collateral damages. But that’s not all. The Lancet has documented the psychological impact of quarantine. The findings offer a glimpse of what is brewing in hundreds of millions of households around the world: a wide range of symptoms of psychological stress and disorder, including low mood, insomnia, anxiety, anger, irritability, emotional exhaustion, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Among them low mood and irritability stand out as being very common… How many societies are equipped to handle such situations with sensitivity?

Humanitarian crisis

So, over and above a health crisis, we are stuck in an economic and labour emergency. In effect, we are saddled with a humanitarian crisis that, alas, not all societies are handling with kid gloves. Economic recession and growing unemployment; labour unrest and resultant law-and-order problems; hunger and disease: isn’t that a magic recipe for the rise of authoritarian leadership? After all, ruling the hearts and minds of a battered people comes easy to the political class. No wonder a curious, novel subservience is in the offing. And as likely as not, the powers-that-be will make hay out of the issue and hammer out a new world order.

That countries on lockdown can’t go anywhere is a myth. Citizens pinned down by covid-19 have lost track of the days, weeks and months, and of what’s cooking in the cauldron of political equations. These have changed, perhaps imperceptibly, in Iran, Israel, and Korea, all of them pre-covid hotspots, not to speak of countries in Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Indian subcontinent. Thankfully, a large section of the media and opinion makers has risen to the occasion. They’ve guarded their independence and stocked us with news of go-downs brim-full even while supermarket shelves lie empty and, what’s more, populations go hungry.

The need of the hour is to protect our sanity and our freedoms. We must seek ways and means of sailing through the storm in a concerted manner. E-commerce has risen to the occasion as though predesigned for the pandemic, said The Economist. The IT and service sectors are due to experience a high. Many others are reinventing themselves in an earnest bid to survive. Individuals and households are rediscovering themselves and rising from the ashes. In many countries, the lockdown has been eased on offices and shopping centres, and people have heaved a sigh of relief.

Power of prayer

Predictably, man does not live by bread alone. Liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship is a must. Public places of worship – traditional havens of spiritual solace – have to stay open with dignity. Necessary protocol devised and followed up to the letter will go a long way towards restoring the confidence levels of the people.

The covid fault line runs deep and is not likely to be repaired anytime soon. At any rate, the world is unlikely to be the same again. We have to brace ourselves up for a long haul and an abnormal, new normal! But when we can’t walk, we mustn’t crawl; we should rather talk and even learn to fly – and we’ll fly best on the wings of prayer. Invincible as we’d thought ourselves to be, did it ever cross our minds that a tiny virus would throw us into a spin? And with the virus shrouded in mystery, the world has fallen on its knees in fervent prayer. This is indeed our safest bet if we wish to call the bluff of a scientific coterie and political mafia, two viruses in a mad swirl.

Credits:

- This is an updated version of the article published in The Goan of 24 May 2020.

- Many thanks to my friend, well known artist Yolanda de Sousa of Studio n Galeria, Calangute, Goa, for permission to use her painting of 23 May 2020, depicting the two viruses in a swirl, as I see them.

- Header by my son Emmanuel de Noronha.

Os vinte cinco anos da Fundação Oriente em Goa...

Entrevista ao Dr. Carlos Monjardino, Presidente do Conselho da Administração da Fundação Oriente, por Óscar de Noronha

ON – Senhor doutor, muito boa tarde, e obrigado por nos receber! E desde já parabéns pelo jubileu da prata da Delegação da Fundação Oriente em Goa!

CM – Boa tarde e muito obrigado! É sempre um prazer.

ON – Que balanço faz aos últimos 25 anos?

CM – Os primeiros anos foram, não digo difíceis, mas demoraram algum tempo a passar. Tínhamos algumas limitações – não muitas, porque desde o início tivemos um grande suporte por parte de quem tinha que nos “fiscalizar”: era o ICCR [Indian Council of Cultural Relations]. E logo a seguir quando eu fui ter com eles em Delhi, para lhes apresentar o primeiro projecto, o primeiro plano de actividades da Fundação aqui, que eu insisti que era para a Índia e não só para Goa, porque na altura, é bom saber, há 25 anos, as relações não eram as que são hoje. E, portanto, expliquei que estaríamos instalados em Goa, mas que a nossa acção ia para além de Goa também, como tinha que ser.

Nessa altura não tivemos quaisquer problemas. Analisaram o nosso plano de actividades. Houve uma única coisa que não quiseram que nós fizessemos, que foi ter uma livraria portuguesa em Goa. Não quiseram (a rir) mas isso também não teve problema nenhum, porque, passado muito pouco tempo, fizemos aqui uma feira de livros – foram duas, aliás, feitas por nosso comum amigo António Alçada Baptista, que gostava muito de Goa e que organizou muito bem essas duas feiras... foram um sucesso imenso.

Pronto, as coisas foram correndo. Fomos apoiando projectos aqui; fomos publicando algumas obras de escritores locais; também todos os anos vamos dando algumas bolsas de estudo; fomos apoiando o ensino de português que até hoje continuamos, e nós hoje temos 14 ou 15 professores de português que, de alguma maneira, têm um apoio nosso para ensinar português aqui...

E, portanto, fomos andando… Temos aquela célebre exposição que todos conhecem, do [António Xavier da] Trindade, lá na delegação da Fundação. É um pintor maior e, portanto, em qualquer sítio do mundo era conhecido como o Rembrandt daqui da zona...

ON - O Rembrandt do Oriente!

CM – ... do Oriente, e fomos surpreendidos com uma doação daquelas obras, mas que aceitámos de imediato com algumas limitações que existiam na altura... Depois adquirimos mais algumas obras do mesmo artista, mas não muitas... Também não há muitas no mercado. E agora vamos fazer uma segunda edição do Xavier Trindade com muitas obras que não foram expostas antes e que serão expostas este ano, lá nas Fontaínhas, na nossa Delegação.

ON – Muito bem. Além disso, a Fundação Oriente fez trabalhos com os nossos edifícios – com o nosso património arquitectónico; e programas de música, como o Festival do Monte!

CM – Sim, quanto à recuperação de edifícios de interesse histórico ou simplesmente arquitectónico aqui em Goa e à volta de Goa, nós, porque tínhamos a noção – o que é normal, enfim – que o que distingue Goa do resto da Índia é que tem uma componente cristã muito grande. E portanto tem as igrejas, tem as capelas e os cruzeiros por aí fora, e nós fomos ajudando nisso, mas depois também sentimos que não podíamos ficar só a apoiar essas iniciativas que nos propunham, e resolvemos ir mais longe do que isso: resolvemos apoiar também uma recuperação dum templo hindu, que para grande espanto de muitas pessoas... –mas estas coisas eu, às vezes, como se costuma dizer, tiro um coelho do chapéu... – e fizemos isso... Foi aceite pelas entidades que controlavam lá o templo hindu e recuperámos o templo hindu. Porque havia sempre umas vozes que diziam ‘porque apoiar sempre as igrejas?’... Eu, claro que tanto apoio as igrejas como apoio os templos hindus. Mas é claro que aqui o que faz mais sentido é apoiar as igrejas porque há uma profusão de igrejas que precisam de ser recuperadas... Mas, pronto, vamos fazendo, temos uma visão muito aberta do que devemos fazer aqui...

ON – Aliás, até calha bem porque os templos hindus aqui são muito diferentes dos templos do resto da Índia. Aqui têm uma característica indo-portuguesa mesmo!

CM – É! Portanto se alguém responsável por alguns templos hindus que tenham que ser recuperados, e que me vá ouvir, podem falar com a dr.ª Inês Figueira [Delegada em Goa], que nós teremos maior prazer em apoiar também a recuperação de templos hindus....

Mas depois também a outra parte que estava a dizer: os festivais de música. O festival da Senhora do Monte para nós tem um significado especial porque há dezoito anos que promovemos aquele festival. Primeiro, começámos por recuperar a Capela [do Monte], que foi um trabalho bastante pesado não só do ponto de vista arquitectónico de recuperação, mas também financeiro. Foi muito pesado. Mas, pronto, foi feito e agora é preciso voltar a fazer alguma manutenção porque com o clima que existe aqui às vezes as coisas vão-se deteriorando rapidamente... E agora há uma nova fase de manutenção e de recuperação duma parte que tem que ser feita também....

ON – Os objectivos da Fundação Oriente variam de país para país...

CM – Variam, consoante o que é a realidade em cada país...

ON – O que é que a Fundação gostaria de fazer, mas ainda não conseguiu fazer na Índia?

CM – Há certamente muitas coisas que a gente gostaria de fazer, mas nós temos cingido àquilo que é possível fazer com os meios que temos – porque os nossos meios também não são ilimitados – e passámos a mensagem de que a Fundação Oriente, que foi criada aqui um pouco por iniciativa do dr. Mário Soares... Quando eu fui para presidente da Fundação – foi ele que me convidou, de resto – me chamou à atenção para uma fundação que eu tinha criado, assim, no papel, antes, em Macau, e depois eu fui para Portugal... Ele chamou-me para eu de facto dar vida à Fundação, coisa que eu fiz... Passado muito pouco tempo, ele telefonou-me e diz-me assim: ‘Ouça lá, você não quer fazer qualquer coisa na Índia? Nós precisamos de reforçar os laços com a Índia; as relações ainda estão um bocadinho tremidas. Talvez fosse bom ter qualquer coisa...’ ‘Claro que estamos, e o natural seria Goa’. E ele diz-me assim: ‘Com certeza. Você vá lá e veja se consegue então uma coisa que era muito importante para Portugal e para a Índia, que houvesse uma instituição que fizesse essa ligação, ou que ajudasse a fazer essa ligação.’

E então eu cá vim, como pessoa bem-comportada – que não sou – mas naquela altura fui – vim cá a mando do dr. Soares, para criar a Delegação cá. E ele tinha a noção de que era necessário naquela altura fazer mais qualquer coisa porque aqui – vocês aqui se calhar não se lembram... vocês são todos muito novos, você incluindo é muito novo – vocês não se lembram que há 25 anos não havia nada de português em Goa...

ON – Sim, a gente aqui em Goa perdeu uma geração... completamente... houve um hiato, mas graças a ...

CM – Pronto, mas não havia nada, não havia Consulado, não havia nada. Não havia o Instituto Camões, não havia nada. Por isso é que a gente assumiu o ensino do português também... Bom, e o Consulado, nem pensar nisso!... Bom. E, portanto, estávamos aqui um bocado sozinhos. Não temos funções consulares, portanto não podíamos substituir-nos ao Consulado, mas iamos fazer aquilo que achámos que podíamos fazer, com grande ajuda do Governo, de então, de Goa... Eram pessoas muito compreensivas, e que entenderam bem aquela ideia que o dr. Soares tinha na cabeça, que era preciso fazer qualquer coisa aqui, na Índia e a partir de Goa.

ON – Mas ainda falta algum passo a tomar? O senhor doutor acha que o Governo da Índia ou o de Goa deve tomar um passo que ajude depois a Fundação a actuar melhor?

CM – Eu acho é que poderia haver... Eu gostaria – gostaria, mas este é um desejo e isto tem outras limitações – eu gostaria que o Governo local estivesse mais próximo daquilo que nós fazemos, mas não está muito... Digo a si, em abono da verdade, não está muito... Houve uma altura, há uns anos atrás, que esteve, razoavelmente próximo.... Agora não vou por aqui dizer nomes porque se não arranjo por aqui um sarilho de todo o tamanho, porque já não são os mesmos partidos... arranjo por aqui uma trapalhada, portanto o melhor é não dar nomes... Mas houve uma altura em que estavam muito próximos daquilo que nós fazíamos. E portanto, gostaria que fizessem mais; que o responsável da Cultura aqui tivesse um melhor interesse naquilo que nós fazemos. E em Delhi também, mas em Delhi eu acho que, apesar de tudo, – é longe – mas apesar de tudo, quando se vai lá eles mostram interesse naquilo que nós fazemos na Índia em geral e em Goa em particular...

ON – Os anos 97 e 99 devem ter sido marcos importantes para a Fundação...

CM – 97, não tanto, 99, sim. Em 97, para a Fundação teve um pouco foi o problema da China e o Hong Kong. A questão de Hong Kong não foi dar em nada. O ano de 99 foi mais importante por causa da saída da administração portuguesa de Macau. Isso foi muito importante.

ON – Mas eu falava dos fundos dos casinos, que cessaram...

CM – Não, já antes não havia nada. Eu já tinha tido uma pega com os chineses – que é o meu costumo arranjar assim umas pegas de vez em quando!... (a rir) Não, porque os chineses não levaram a bem que a Fundação tivesse sede em Lisboa e não em Macau. Portanto criou-se ali um mal-estar, e esse mal-estar levou a que eu tivesse que ceder – o que é difícil, porque normalmente eu não cedo com muita facilidade! Em 1997, com efeitos retroactivos em 96, deixámos de receber dinheiro local... E era muito dinheiro que recebíamos de Macau.

ON – Exacto! No entanto, a Fundação soube gerir as coisas: investiu noutros lugares, etc...

CM – A Fundação soube investir e tinha guardado uma almofada grande em termos de liquidez, não gastando tudo aquilo que tinha recebido do passado e pondo de parte... Eu não adivinhava o que ia acontecer, mas felizmente pus de parte uma parte substancial daquilo que tínhamos recebido no passado – coisa que as pessoas me acusavam muito, dizendo: ‘Recebe tanto dinheiro e gasta tão pouco!’ E eu disse: ‘Olhe, é para outros dias.’ Olhe, eles vieram – os dias mais complicados vieram depois. Mas tivemos muita sorte e algum saber... Já não gosto de dizer isso porque quem faz os investimentos sou eu...

Fizemos dois ou três muito bons investimentos que criaram mais valias importantíssimas para a Fundação... Para lhe dar uma idéia – esta é uma área de que as pessoas acham graça, mas que é um bocado árida – nós hoje temos em termos de activos praticamente a mesma coisa do que tínhamos quando começámos a Fundação. E já gastámos para cima de uma fortuna nestes 25 anos, porque ao princípio gastámos muito dinheiro na China, muito mais, se calhar, do que devíamos ter gasto, mas nós tínhamos que afirmar uma posição na China, portanto fizemos um esforço grande em relação a subsídios para a China e, depois, em Macau, e só um bocado depois é que nos virámos para Portugal. E só começámos a trabalhar mais a sério com Portugal já passados alguns anos porque era a altura, fizemos o Museu [do Oriente], que também foi um investimento particularmente grande e onde temos peças indianas muito bonitas ...

ON – A “almofada” de que o senhor doutor falava ajudou a absorver todos os choques dessas bruscas mudanças económicas que houve na Europa...

CM – Exactamente, exactamente!

ON – Apesar de todos os problemas, conseguiu abrir um Museu de que agora falou e que, se calhar, é o maior projecto da Fundação até hoje...

CM – Sim, é o maior projecto da Fundação até hoje. As pessoas gostam muito do Museu. É de facto um museu muito activo, interactivo mesmo. Em Portugal é de longe o museu com mais actividades, para miúdos, para crianças e para jovens. E tem várias componentes: tem yoga... tem tudo! É, portanto, um museu curioso, muito diferente dos outros museus que há por lá. Mas foi de facto um projecto maior que, financeiramente mais pesado... mas está lá... É aquilo, e pronto, nós, a Administração, temos agora encostado ao Museu um edifício que é o nosso edifício da Administração, que do edifício que estava no meio da cidade passou para ali... e agora estamos todos juntos. É um projecto que hoje é um todo que faz sentido...

ON – O senhor doutor passou do sector governamental para o sector privado...

CM – Não, passei do sector privado muito brevemente para o sector governamental, como você diz, e depois rapidamente também saí outra vez e voltei. Não é que tenha algo contra o público, não tenho; antes pelo contrário, mas a vida é assim. Tive aquela oportunidade que me foi dada pelo dr. Soares para ir para Macau, e estive em Macau 14 meses, não estive mais, e voltei outra vez para o privado...

ON – E o que significa para o doutor, pessoalmente, o ter estado à testa da Fundação Oriente há 32 anos?

CM – 32 anos: o que é que significa? Significa que estou velho! (a rir) Não, significa que apesar de tudo é interessante – eu não escondo – acompanhar um projecto que eu próprio criei. Isso é interessante para mim ver a evolução da Fundação com uma forma sólida: é isso, e de outra forma não poderia ser, porque eu sou conhecido – e pergunte ali à dr.ª Inês, ela dirá a mesma coisa – eu sou muito agarrado ao dinheiro, de maneira que estou sempre a fazer poupanças em tudo...

ON – E faz bem, porque o senhor doutor disse uma vez que sem dinheiro não se faz nada... não se faz cultura!...

CM – Pois não! Não se faz cultura, não se faz nada! Às vezes as pessoas da Cultura não funcionam bem assim. Acham que o dinheiro tem que aparecer de algum lado, mas não querem saber de onde. Lançam-se e dizem: ‘Ah, agora o dinheiro há-de aparecer.’ Mas não é assim; não é assim, e de facto, sem dinheiro não se faz rigorosamente nada! Por isso é preciso, antes de mais nada, meter uma gestão sã nos activos deste tipo de instituições como doutros, e é preciso fazê-lo...

ON – Temos que agradecer ao senhor doutor por todo o trabalho que a Fundação tem feito aqui por Goa. E queria saber quais os seus sonhos para o próximo futuro...

CM – Os meus sonhos?! Eu já estou velho para ter muitos sonhos! Vou tendo alguns, apesar de tudo! Bom, aqui em Goa? Eu nunca pus de parte completamente a hipótese, noutro campo que não cultural, de investir em Goa. Houve uma altura em que ainda pensei em investir na hotelaria porque a Fundação tinha várias participações na hotelaria, e ainda tem. Tem em Timor um hotel, em Lisboa neste momento só tem um. Mas na área grande de Lisboa, tem um. E pensei depois: é muito longe! E para gerir as coisas assim, à distância, é complicado, portanto esse projecto não avançou. Mas se aparecer um outro projecto qualquer, não digo que não a estudar um eventual investimento aqui em Goa.

ON – Entretanto continuam com as coisas que já começaram... A Delegação aqui está a fazer um belíssimo papel...

CM – Espero que considerem que sim!

ON – Sim! Sim, sim!

CM – Se não temos que agarrar aí a dr.ª Inês! (a rir)

ON – Então, senhor doutor, com isto agradecemos muito esta conversa e desejamos muitos anos de vida para o senhor doutor – que continue com os sonhos – e todo o sucesso para a Delegação da Fundação Oriente em Goa!

CM – Muito obrigado, muito obrigado!

ON – Muito obrigado sou eu.

(Entrevista radiodifundida em 23 de fevereiro de 2020, no programa Renascença Goa, acessível no You Tube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4HqO1k5iDX4; e publicada na Revista da Casa de Goa, II Série, No. 4, Maio-Junho 2020)

St Joseph: unsuspecting, silent, forgotten

Those three adjectives popped into my head as I spent 1 May pondering the life of the foster father of Jesus. And come to think of it, what do we really know about him? Except for some passages in Matthew and Luke, even the Scriptures have scanty information on his life journey.

Trust and wisdom

Joseph, who was a descendant of the house of King David, exhibited no trappings of royalty. He was only betrothed to Mary, a virgin, when, mysteriously, he found her pregnant. He graciously refrained from condemning her; as “a righteous man and unwilling to expose her to public disgrace” (Mt 1:19), he'd thought of discreetly divorcing her. But this would surely have left the maiden defenceless against a bigoted Jewish society – or so it dawned on him after an angel revealed him God’s magnificent designs. Trusting the divine messenger, he promptly took Mary as his wife. Thus, the role of Joseph who was blessed with expectant faith and total trust would soon prove to be crucial in the history of salvation.

What was Joseph like, as a husband and father, professional and citizen? One thing is for sure – he wasn’t a loudmouth; quietness was his watchword. Soon after Jesus’ birth, he quietly fled with the family to Egypt, escaping carnage of infants at the hands of king Herod of Judea. They returned only after the ruler’s death and settled in Nazareth, far from the glare of the capital city, Jerusalem. He worked as a modest carpenter, and was helped by his divine son. A dutiful citizen that he was, he’d earlier made a trip to his city, Bethlehem, to enrol the couple in the census. Finally, Joseph was a devoted father too; he joined Mary in searching for their son lost in Jerusalem. But then, quite perplexingly, even here we don’t get to hear his voice.

Pope Benedict XVI has stated that Joseph led a “simple and industrious life, cultivating the conjugal relationship with care and fulfilled with enthusiasm the great and difficult educational mission.” (Angelus, St Peter's Square, 19 March 2006) Yet, in modern parlance, we tend to dismiss such a man as lacking l’esprit. So, could it be that Joseph’s portrayal as an old and unattractive man induced the silence that we’ve weaved around him down the centuries? Some believe that his elderly mien is meant to account for his wisdom fit for the father of Jesus. And hopefully, showing him as past his prime would help explain how he abstained from conjugal relations with a young and pretty wife.

While the Pope Emeritus makes ample references to how Joseph treated Mary with love and care, Fulton Sheen, portrays the Saint more dramatically, in The World’s First Love. He profiles him as “probably a young man, strong, virile, athletic, handsome, chaste, and disciplined, the kind of man one sees… working at a carpenter’s bench.” Although society then was probably less conscious of physical attributes than we are today, those are some that would rightly distinguish the holy family of Nazareth. And practically speaking, how else would a man provide for a family of three?

The insightful Archbishop has a take on Joseph’s libido as well: “Instead of being a man incapable of loving, he must have been on fire with love.” But, then, as a counterpoint he sheds light on how “young girls in those days, like Mary, took vows to love God uniquely, and so did young men, of whom Joseph was one so preeminent as to be called the ‘just’. Instead, then, of being dried fruit to be served on the table of the King, he was rather a blossom filled with promise and power. He was not in the evening of life, but in its morning, bubbling over with energy, strength, and controlled passion.”

That’s how Joseph must have lived the elevated life that God had called him for. The circumstances of his death are unknown, but it is surmised that he died before Jesus’ public life began, if not, certainly before the Crucifixion (Jn 19: 26-27). We could reason out that God thus saved him the anxiety of seeing Jesus vilified in his public ministry: really, how would a father – an honourable man – take it lying down? It might have well compelled him to come out into the open and defend his son. But if this conjecture be false, God for sure saved him from the cruelty of witnessing the humiliating death of his Son on the Cross.

Honouring Joseph

Be that as it may, Joseph was an unsuspecting man, for he trusted in the Lord; he was silent, as he knew how to take it all in his stride. So now the moot question is: why do we forget him so very easily?

Curiously, veneration of Joseph began in his land of self-exile, Egypt, and the same took about thirteen centuries to take root in the West. This finally happened when the Servites, an order of mendicant friars, began to observe his feast on 19 March, the traditional day of his death.

Later promoters of the devotion included Pope Sixtus IV, who introduced the feast circa 1479, and the celebrated sixteenth-century mystic St Teresa of Avila, who attributed her miraculous cure of paralysis to him. After Mexico, Canada, and Belgium declared Joseph their patron, Pope Pius IX in 1870 declared him patron of the Universal Church. In 1955, Pope Pius XII established the Feast of St Joseph the Worker on 1 May as a counter-celebration to the communist-sponsored May Day.

A feast day, however, should rise above tokenism. We must therefore have recourse to this admirable saint – emblematic of the world's forgotten fathers – in the ups-and-downs of our daily life. No artist or writer has captured the essence of the man as beautifully as the litany in his honour has: “St. Joseph – chaste guardian of the Virgin, foster father of the Son of God, diligent protector of Christ, head of the Holy Family, most just, most chaste, most prudent, most strong, most obedient, most faithful.”

Closer to our times, Pope Benedict XVI highlighted a much neglected aspect of Joseph’s life – chastity – by introducing the reference in the Eucharistic prayer, after Mary: “St Joseph, her Most Chaste Spouse”. (Why many celebrants avoid the operative word is anybody’s guess) The Pope revealed that his predecessor, John Paul II, who was devoted to St Joseph, and dedicated to him the Apostolic Exhortation Redemptoris Custos (Guardian of the Redeemer), experienced his assistance at the hour of death.

In an era when fatherhood is relegated to the background even in birth certificates; masculinity is equated with machismo; and chastity disdained in the age of the sexual revolution, we are invited to emulate the counterexample of St Joseph.

In particular, on 1 May, let us make Pope Pius X’s Prayer to the Model of Workers our own, so that our labour and toil may draw abundant fruit in this valley of tears, particularly given the rapid and complex changes due to happen in the covid and post-covid eras.

(To the memory of my parents Fernando de Noronha and Judite da Veiga, on their 56th wedding anniversary)

Credits:

Pic 1 - Statue at Our Lady of the Rosary Church, Heralds of the Gospel Seminary, Caeiras, Greater São Paulo, Brazil. Taken from the magazine of the Heralds of the Gospel (Vol. V, No. 43, May 2011)

Pic 2 - Frame that my parents made it a point to gift to each of their five sons at their marriage.

Pic 3 - Death of St Joseph: panel of the Church of Our Lady (Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk, Amsterdam). Information provided by my friend Caetano Filipe Colaço (Margão/Dona Paula)

Pic 4 - Prayer to St Joseph, Model of Workers, composed by St Pius X. Source: magazine of the Heralds of the Gospel (as above)

(Also published in The Examiner, December 2021)

He has risen, Alleluia!

EASTER SUNDAY 2020

Readings: Acts 10: 34a, 37-43; Ps 117: 1-2, 16-17, 22-23; Col 3: 1-4; Jn 20: 1-9

After a quarantine marked by a grim Liturgy of the Word followed up by a Triduum of hope, the day has finally come when our Light, Life and Hope has broken all barriers and made Himself manifest. What joy for those who observed the Lenten period in prayer, fasting and almsgiving!

Nine readings are prescribed for the Easter Sunday Vigil Mass, seven from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament. But let’s restrict ourselves to the three readings prescribed for the Easter Sunday morning Mass.

Today begins a new cycle of readings, all of them from the New Testament writers. Particularly the first reading – from the Acts of the Apostles – will go on uninterruptedly up to Pentecost Sunday (with the exception of the Vigil Mass). This fifth book of the New Testament, written in all probability by the Evangelist Luke, provides a valuable history of the early Christian church.

Today, we see Peter joyfully announcing that Christ has risen. A man who lived with Jesus vouches that He is not just a man: anointed by God’s Spirit, He has the fullness of God in Him. He is undoubtedly the Messiah, who showed His true nature by way of miracles, of which the Resurrection is the most definitive. He is the Life who has conquered death. He has commanded Peter and the other apostles “to testify that He is the one ordained by God to be the judge of the living and the dead.” He is the Saviour whom all of humankind is invited to follow and accept, and “everyone who believes in Him receives forgiveness of sins through His name.”

Peter, who had once lost it and denied his Master, now speaks with the courage of his convictions. He is already showing up as the leader of the nascent Apostolic College. And so was it with Paul. He had persecuted Christ but now, filled with the Holy Spirit, he urges others to follow Christ. Pointing at the One “who is seated at the right hand of God”, he vouches that “when Christ who is our life appears, then you also will appear with him in glory.” We too, by our baptism, have died to sin and risen with Christ to a new life. Hence, in the world in which we live, whatever our station in life, we are duty-bound to work towards our collective happiness on earth but never forgetting that Heaven is our final destination.

Indeed Christ’s Resurrection is His glory. What a slap it was to those who didn’t believe and put to Him to death. Against facts there are no arguments! At first, only a few remembered Him, had faith and persevered. One of them was Mary Magdalene. She came to the tomb and, wonder of wonders, the stone had been rolled away! Did she understand what had happened? Was she scared? She suspected sabotage, as we can conclude from what she told Simon Peter and John. When these two reached the tomb, they saw and believed. Mind you, till that moment “they did not know the scripture”, that is to say, they’d never understood what Jesus had told them in his three-year ministry. Only just now it dawned on them that He had really risen from the dead!

Don’t we too go through many Lents and Easters of our life as though they are mere rituals? Let’s hope that our faith has progressed such that this year it has dawned on us that Christ really rose two thousand years ago after an excruciating Passion and Death. Let’s believe and testify that He does so every day at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. This is what is meant by the "Real Presence" of Christ in the Eucharist. The Risen Christ is present to his Church in many ways but most especially sacramentally, through His Body and Blood.

Never again, my Lord!

LENT 2020 – Day 45

Readings: Is 52: 13-53, 12; Ps 30: 2.6, 12 13, 15-16 17.25; Heb 4: 14-16, 5.7-9; Jn 18: 1-9, 42

Isn’t it amazing that the saga of Jesus Christ was charted eight centuries before the coming of the Messiah? In the fourth Servant Song, Prophet Isaiah speaks of the One who God would choose to free His people from oppression. He would carry out His mission as Servant of God, in humility and pain. He would teach but they would despise and reject Him. With His appearance marred beyond human semblance, this man of sorrows would carry our sorrows. He would be wounded not for His sins but for ours; He would do no violence nor show deceit, yet He would be punished; He would not utter a word but let Himself be taken like a lamb to the slaughter. The punishment He would bear would heal humankind, and God would exalt and lift up the Servant.

St John the Evangelist, the favourite disciple of Jesus who most closely lived His Passion, captured it all so vividly. The Son of God was indeed despised and rejected, denied by one of His own, Peter the Rock, and betrayed by another, Judas Iscariot. As this was also the theme of the Gospel according to St Matthew on Passion Sunday, today let’s focus on the crux of Good Friday: the unfair trial of our Lord which led to His death.

The Jewish authorities put forth religious motives justifying the death of Jesus. However, the Jewish leaders had powers to impose only flogging and prison, not death. By making Jesus look like a political conspirator, they took Him to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. It was a flimsy accusation, Pilate learnt, yet he told the people to judge Him according to their law. He proved an ineffectual, vacillating man. Even after Jesus clarified that His kingship was not of this world, Pilate lacked the courage to face the crowd whom the Sanhedrin chiefs had instigated. The Messiah touched a raw nerve in Pilate when he said, “I have come into the world to bear witness to the truth.”

Then, perhaps in jest, Pilate famously said, “What is truth?’ His own rhetoric shook him out of his complacency at least temporarily. He went out to the Jews again and told them, “I find no crime in Him.” But soon thereafter this weak and pliable judge washed his hands off the gross injustice that the mob wanted to mete out to the most just man on earth. He consented to HIs crucifixion, as demanded by the rabble outside his palace. Through all of this the only act to which Pilate did not bend was to change the title “King of the Jews” that he had already put down. Thus, unwittingly, he who had earlier said, “So you are a king?” now crowned Jesus who had then answered, “You say that I am a king.”

We see that Pilate who had power to save Jesus proved powerless, simply because he wanted to save his skin. And so did the chief priests: didn’t they bend over backwards when they said, “We have no king but Caesar”? While they showed their true colours, suffering did not overwhelm Jesus. Very dignified, He went ahead to meet His death. And when He reached the appointed place and hour, one of the crucified criminals, with a humble and repentant heart, did what the learned and vicious of Jewish society did not have the gumption to do, that is, acknowledge that Jesus is God.

In this picture of desolation, three Marys stood at the foot of the Cross: Mary, the mother of Jesus, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Copas, and Mary Magdalene. Women, the less powerful and voiceless in Jewish society, comforted Jesus every step of the painful way to Calvary. We also know that the meek and simple Simon of Cyrene shared the burden of the Cross for a while, and finally an old and secret disciple Joseph of Arimathea took charge of the body of Jesus and laid it in an absolutely new tomb.

St John’s Gospel passage should convince us that this was the most unfair trial in history. Injustice was meted out to the long-awaited Messiah. About this we have to be thoroughly convinced and refrain from being unfair to Jesus in our daily lives. Aren’t He and the Church often detested because they bear witness to the truth? And what do we do? We remain in our own comfort zones and wash our hands of it like Pilate. Isn’t our Lord mocked at and His laws struck down? And what do we do? We let Judases, Caiaphases and Pilates walk free and even rule over us.

Well, every time we fail to fearlessly defend Our Lord, we let Calvary be real in our own lives. But never again, my Lord! We who’ve been waiting for the Messiah for millennia now must say, Never again! He will soon rise from the dead and walk into our lives if we let Him do so. He is our high priest who can sympathise with our weaknesses. Let us with confidence, then, as St Paul’s exhorts us, “draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need.”

The Lord calls us to love one another

LENT 2020 – Day 44

Readings: Ex 12: 1-8, 11-14; Ps 115: 12-13, 15-16, 17-18; Cor 11: 23-26; Jn 13: 1-15

Maundy Thursday is the first day of the Easter Triduum. The readings of the Mass of the Lord’s Supper form a bridge between the historic liberation of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt and the final liberation of the world from the bondage of sin.

The reading from the Book of Exodus points to the origin of Israel as God’s Chosen People. The Lord commands that this month be the first of the year, in commemoration of the beginning of their liberation. He ordains on how to observe the Paschal rituals. These foster a feeling of religious community through the sharing of the paschal lamb. The staining of doorposts with blood of the expiatory lamb is the stamp of the divine that wards off all evil. Unleavened bread eaten in haste accompanied by bitter herbs is a symbol of the suffering from which the Israelites had fled.

When the twelve Apostles celebrated the Passover with their Master, they followed the traditional rite evoking the old covenants. It was also a thanksgiving for God’s many interventions to rescue the Israelites. What the Apostles did not realize, however, was that the Last Supper marked a new beginning. Jesus had anticipated Calvary where He would be presenting Himself as the paschal lamb, the Lamb of God. He did so mysteriously, by converting bread and wine into His Body and Blood. The Son of God made this supreme act of love so as to redeem the sins of humankind. The Holy Mass thus established became the bloodless Sacrifice of the New Covenant.

The Eucharist is a masterpiece of Jesus’ love, the best proof of His love for humankind. He made the Apostles participants in His Priesthood and ordained them to carry out that mystery. He gave them responsibilities and authority: to bind and loose in His name, to forgive sins, to transform the bread and wine into His Body and Blood. This the ordained priesthood would do infinite times, until the Lord’s return to the world. Their role is vital in helping the faithful to carry out their baptismal priesthood.

There was no better occasion than the Last Supper for the Lord to command His followers to love one another. He said, “A new commandment I give unto you, that ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another. By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another.” (Jn 13: 34-35) This new commandment is a summary of all of God's law and brings about the definitive liberation.

Speaking to the first Christians, St Paul reiterated that this liberation emerged when the Paschal Lamb, who is the Christ, was sacrificed. Given that we Christians aren’t always united in love, we must take seriously the reminder from the Apostle of the Gentiles: that the Eucharist and the Church – the Sacramental Body and the Mystical Body – are intimately connected. We should place ourselves at the service of our brethren, in humility and love, of which the washing of the Apostles’ feet by our Lord is emblematic. A Eucharist celebrated amidst division cannot be a sign that we are followers of Christ.

The time to be a person of integrity is now

LENT 2020 – Day 43

Readings: Is 50: 4-9a; Ps 68: 8-10, 21-22, 31.33-34; Mt 26: 14-25

The first reading from the Book of Isaiah is practically the same as that of Palm or Passion Sunday. Isaiah talks of his prophetic mission: of how the Lord spoke to him and how he went ahead with faith and courage. He accepted suffering with patience, always expecting the Lord’s help at the right moment.

Suffering is not always physical; very often it is of the moral order. This leads us to sever ties with unprincipled persons, which may even include family and friends. But can any suffering – physical or moral – be worse than what the Lord endured? No. We could therefore consider even our little troubles as our sharing in the Lord’s Cross.

The Gospel passage, which is just a tiny extract from the Sunday text, focuses on Judas’ betrayal which caused moral and physical suffering to the Lord. The place of action was the Passover meal that the disciples had prepared in accordance with instructions from their Master. As they were at the table Jesus saw the movement of His disciples’ hearts. Our Lord first saw the dishonourable act that Judas was going to perpetrate; He saw it even before the consummated the deal with the chief priest.

St Matthew tells us that after Judas had dipped his hand in the dish with Jesus, Satan entered the apostle’s heart. What Judas had actually envisioned only he and God know! Perhaps used to seeing things through the prism of money, here was an occasion to make a fast buck. But did he foresee the serious consequence of his action? Maybe he did. Or maybe he didn’t, for later he wished to retrace his steps. But it was too late to change.

We may not be at the level of the proverbial Judas but we too have failed our Lord. Even if we don’t commit a serious crime, abetment is bad enough. But knowing human nature, God instituted the sacrament of Confession, whereby we can reconcile ourselves to God and win back His grace and favour.

Getting to know Judas’ act at close quarters is surely a traumatic experience. It is a supreme lesson on one of the most painful experiences that one might experience in life. Betrayal often begins with small things: lies, compromises and opportunistic behaviour. If left unchecked by self, parents or other authorities, it grows into unfaithfulness in great things, or what we commonly dub back-stabbing. Lack of integrity that begins with the individual can infect an entire society. Thus public men in a Godless society soon become unprincipled and corrupt.

In all that we do, let’s strive towards the greatest level of integrity: loyalty and faithfulness to God and neighbour. “Whatever is true, whatever is honourable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things,” says St Paul in his letter to the Philippians (4: 8). This is sure to promote a welcome sweetness and an integrity that is pleasing to God by whom we are called into the fellowship of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord (1 Cor 1: 9).

By His side, in His darkest hour

LENT 2020 – Day 42

Readings: Is 49: 1-6; Ps 70: 1-2, 3-4, 5-6, 15-17; Jn 13: 21-33, 36-38

The text of Isaiah’s second servant song speaks of his prophetic mission assigned by the Lord God. He has a message of great import for Israel: the Chosen People are to return to the right path and fulfil their vocation as light to the nations. Holding them in high regard, the Lord God urged them to accept and then take His message of salvation to the ends of the world.

Was it a tall order? Maybe it was, but then they could always rest assured of the Lord’s help. They had only to ask with expectant faith and success would be theirs. The Lord is always our refuge, our justice; He pays heed and saves us. The Lord is our rock, a mighty stronghold. He is our hope, our trust, our help. Every person that has tasted of the Lord’s generous hand will tell of His justice, of his help; his heart will overflow with the Lord’s teachings and His mighty wonders.

What, then, was the problem with Israel? Theirs was indeed a long and sad story. They failed to appreciate the marvels and settled on trinkets. Busy with their petty lives, by and by they forgot the Lord God. They set aside the covenants and began to do their own thing. Their lack of earnestness in God’s things soon gave way to flouting His commandments. The Israelites had long taken the Lord for granted, and they finally paid the price.

Let’s face it. They betrayed the Lord… much as we do when we feign ignorance of our religious duties or are busy with our other duties. We do so because it suits us at that moment. But then, it’s not God who needs us; we need God. He is infinitely powerful and all is grist that comes to His mill. When Judas leaves the scene, Jesus talks freely to His reduced but true flock. He waxes eloquent – “Now is the Son of man glorified, and in him God is glorified; if God is glorified in him, God will also glorify him in himself, and glorify him at once.”

Meanwhile, Jesus is in the goodbye mode: He is going back to the Father who will glorify Him very soon. He also has words of encouragement and consolation for the Apostles and for those who thirst for the living water. Not that He has any dreamy notions about men and women: He knows that we are prone to deny Him – like Peter who disowned Him at His most grievous hour. It’s not that He needed Peter; legions of angels could have come to our Lord’s rescue at that moment. It’s just that He wanted Peter to side with Him… But, of course, Jesus knew the difference between Peter’s moment of denial and Judas’ cold-blooded betrayal.

He wants us to be by His side; He wants us the warmth of our presence; Jesus wants us to be there – for Him – in His darkest hour. And why so? So that He can then pay us back a hundredfold, as is His wont… So let’s never forget the love and faithfulness of the Lord and ask for His grace, by saying, “The Lord is my light and my salvation.”