Memories of the Tridentine Mass - 2/2

First, some history about the Old Goa chapel, which is closely associated with St. Francis Xavier’s memory. Whether or not he built it, he often said Mass there. He quenched his thirst at a nearby well and rinsed his dusty feet at another. This happened after his rounds of the churches, where he taught catechism, and the hospitals, where he tended to lepers and others. The chapel and the wells, which were formerly within the enclosure of the College of St Paul, where St Francis Xavier was once the Rector, have long been pilgrimage spots.

One day, either inside the chapel or at that site, the Jesuit missionary was so overpowered by devotional fervour as he prayed that he felt almost suffocated. Opening his cassock near his chest, he exclaimed, ‘Satis est, Domine, satis est!’ (Enough, Lord, enough).[1] There are others who say that it was a vision of heaven that comforted him in his Oriental toils.[2] This incident is said to have been crucial either in changing the name of the chapel from St Jerome to St Francis Xavier, or, if there was no chapel there, the present one was possibly built to commemorate the heavenly occurrence.

Coming now to the day I attended a Tridentine Mass in the said chapel… It was the 3rd of December 2024. Neither the nip in the air nor the traffic congestion on the feast day prevented people from flocking to the place. Despite the location being a kilometre away from the Basilica, which was the epicentre of the day’s action, I could not easily find a parking spot in the vicinity of the chapel. Men, women, and children in their Sunday best had come from far and wide, and some more were trooping up the gentle slope to the chapel. It took me back to the days when people used to make a beeline to church or chapel on Sundays and feast days…

Coming now to the day I attended a Tridentine Mass in the said chapel… It was the 3rd of December 2024. Neither the nip in the air nor the traffic congestion on the feast day prevented people from flocking to the place. Despite the location being a kilometre away from the Basilica, which was the epicentre of the day’s action, I could not easily find a parking spot in the vicinity of the chapel. Men, women, and children in their Sunday best had come from far and wide, and some more were trooping up the gentle slope to the chapel. It took me back to the days when people used to make a beeline to church or chapel on Sundays and feast days…

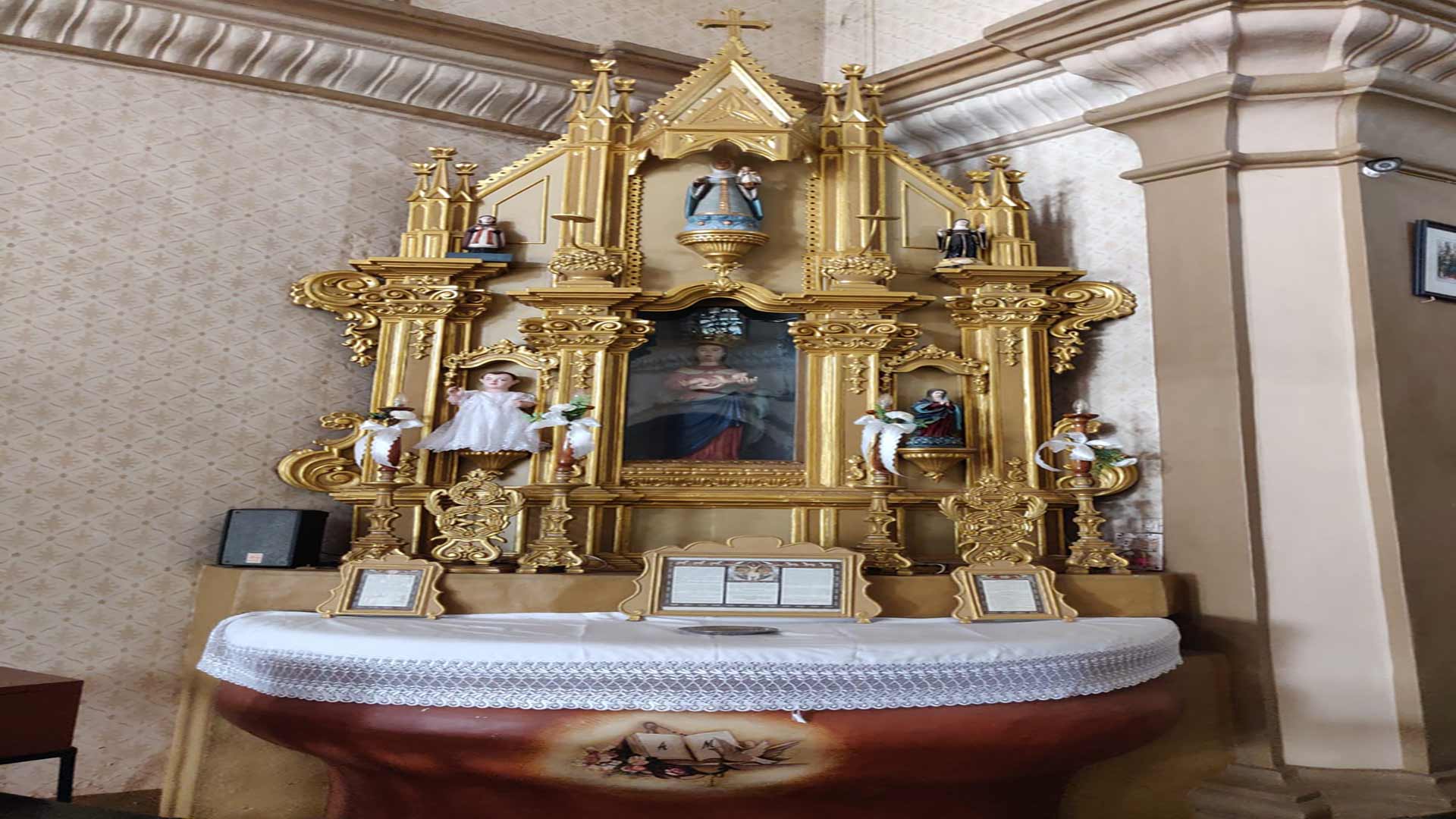

When I arrived, I found the congregation eagerly waiting for the Mass. Their prayerful posture touched my soul. In a few minutes, a priest, attired de rigueur in a black cassock, arrived with the acolytes to ensure that everything was in place. The incense smell and the reverential silence magnified my sense of anticipation, and I felt good when the Mass began. There was nothing difficult or strange about it. Latin came across as my very own.

I could also relate to the parts of the Traditional Latin Mass. The canon has remained largely unchanged since the time of Pope Gregory the Great. The Mass includes more invocations to the Trinity, Mary, and saints than the Novus Ordo Mass. The Lectionary is incensed before the reading of the Gospel. The administration of Holy Communion too is impressive. It is a defining moment. At the chapel, the communicants knelt at the place where a special railing once stood and received the sacred host on the tongue. Reverence and awe were unmistakable. I felt drawn closer to the Holy Presence of God; I felt a sense of belonging to God’s City.

Finally, a word about the sermon. This is a part of the Mass meant for instruction: to explain the biblical readings and prepare the faithful for other sacred rites that follow. The priest, Fr. João Silveira, a Portuguese, who belongs to the Missionaries of the Holy Cross, preached in English, as it is a standard practice in the Traditional Latin Mass to have the sermon in the local language for the congregation’s understanding. The aura of the consecrated minister spoke louder than words.

After the Mass, the congregation greeted each other outside. Godly conversation. The most important item available for everyone to share was the water from the same well from which St. Francis Xavier drank. I heard pilgrims testifying to its healing properties for both the body and soul. Some claimed that they had visions of the Saint of Old Goa as they looked inside the well.

While I am grateful to the hundreds of priests whose Masses I have attended and prayed at in the last half-century, as I returned home that afternoon, I considered the irony of favouring local languages and congregation-facing altars to bring the Mass to the people, for alas, people nowadays fail to bring themselves to the Mass as they did it in illo tempore…

[1] J. N. da Fonseca, An Historical and Archaeological Sketch of the City of Goa (Bombay: Thacker & Co, 1878), pp. 266-268.

[2] Velha Goa: Guia Histórico (Goa: Edição da Repartição Central da Estatística e Informação, 1952), p. 123.

Memories of the Tridentine Mass

I recall attending the Tridentine Mass until I was five or so. My memories of it would have vanished had it not been for the day I discovered a dramatic change in the Mass format. The altar now faced the congregation and the Mass was held in the local language. Much later, I understood that the Second Vatican Council (1962-67) had mandated a change to accommodate the ‘Novus Ordo’ or the New Rite. This was meant to bring the Mass closer to the people in a more literal sense.

There was a change in the liturgy. Pope Paul VI promulgated liturgical books in 1969, and their adoption into the Roman rite began in 1970. In Goa, it changed entirely to Konkani, English, or Portuguese. I still have Goa’s first edition of the rite booklet in Portuguese, which my father gave me. I worried about my reading being out of pace with the celebrant’s and felt reassured when my father said that it would not be so for too long.

However, distrusting my own emotions, I kept it to myself that the Mass did not feel as calm and quiet as before. By the time of my First Holy Communion in 1972, there were plenty of new hymns in English and Konkani, the former of which were quite peppy. The priest-led choir seemed far happier than the congregation, at least in my parish.

Again, the older priests here delivered sermons while the younger ones seemed trained for homilies. The people took to these, yet some men continued the old practice of stepping out of the church for a smoke or a chat. Men’s smoking and women’s wearing of veils possibly ended in the late 1970s. Gender segregation also disappeared: men no longer sat exclusively in the rear pews and women in the front ones.

Therefore, after all these years, I jumped at the opportunity to attend a Vetus Ordo (Old Order) Mass with a good measure of saudade (nostalgia). It was to be held at a historic chapel dedicated to St Francis Xavier in Old Goa. Just the thought of it brought back memories of my parents, who had lovingly introduced me to the Mass, and my grandmothers, who had passed down piety through example. Above all, it was the richness of the liturgy in Latin and the solemnity of the Gregorian chant that made me truly want to attend.

In the run-up to that day, I ruminated on why the old form of the Mass was discontinued in the first place. Curiously, it was never officially stopped, but it was made to look obsolete by not being promoted or even spoken about. Some blamed it on Latin, which they dubbed difficult and strange. since Pope Pius V standardized the Roman Rite through the Roman Missal?

Come to think of it, can one ever feel out of place when visiting one’s paternal home, even if it is after half a century? Likewise, can a language ever feel foreign if it is our very own mother tongue—the official language of the Mother Church? The Tridentine Mass is the same Mass that St Francis Xavier said as he went about Christianizing Goa and India. Latin is the same language that our ancestors heard, sang in, read, and loved down the centuries.

Hence, on the occasion of the solemn Exposition of the Sacred Remains of St Francis Xavier last year, I decided to attend a Traditional Latin Mass, and I gratefully recall the day.

(to be continued tomorrow)

Panjim Church bell strikes 150

Panjim’s Immaculate Conception Church, with its zigzag stairway and whitewashed exterior, is a major attraction. Sitting high up on Conceição Hill, it crowns the city-centre landscape to a tee. No one goes by without looking twice at the majestic edifice or stopping to hear the church bells ringing. The rich and mellow tone of the main bell is a gift to the city’s soundscape. Today marks the day when it was first heard from the belfry 150 years ago.

The bell has a long history of travel. It was cast in 1749 by João Nicolau Levachi of the Royal Foundry of Lisbon, by order of Friar José de São Patrício, Prior of the Augustinian monastery in the Rome of East. It was a perfect match for Our Lady of Grace, the city’s grandest church. In 1841, as the monasterial church was inoperative, following the extinction of the Religious Orders, Governor José Joaquim Lopes de Lima shifted the bell to the Aguada Lighthouse. The clock regulating the eclipses struck the hours on this bell. This arrangement lasted for three decades (1841-71), until it was replaced by the Argand system.

The approximately 2.25-ton bell (diameter 2 m, height 1.8 m), Goa’s second largest after the Cathedral See’s Golden Bell, was then assigned to the Panjim parish church. In a daring project undertaken by machinist António Felix da Costa of Siolim in November 1874, the bell was transported on two canoes and offloaded at Cais dos Camotins (a wharf next to the Mhamai Kamats). It was hung on two thick makeshift columns, close to the cemetery behind the church, and was first rung on the feast’s eve that year.

The work on the architectural modification of the frontispiece began in August 1875. Then came the final stage of Costa’s ingenuity. By 26 November, the scaffolding was in position. The massive bell suspended from a pulley was raised slowly to the central belfry specially built for it. The spectators were amazed. Te Deum laudamus was sung on this day as well as on 1 December 1875, when the bell was rung from the apex for the first time.

It was not just another day in Goa. Those engineering feats deserved front-page coverage, except that Goa did not have a daily. In the former capital city, now called Old Goa, preparations were underway for the third solemn Exposition of St Francis Xavier. In Panjim, the new capital, officially called Nova Goa, the city centre was almost picture-perfect, with the Senate’s imposing clock tower building, the public promenade (today’s municipal garden), and the elegant Largo 13 de Junho, now Church Square. Only Corte de Oiteiro was left to complete the scene as it stands today.

It is quite another matter that a serious mishap tarnished the third anniversary of the installation of the Levachi bell. On the evening of Sunday, 1 December 1878, the third day of the novena to the Immaculate Conception, while the bells were ringing and the faithful were exiting the church, a hook bolt of the main bell came loose and fell on a devotee, Camilo Cipriano Barreto Pereira, causing a deep cut in his skull. According to the Orlim-based weekly A Índia Portuguesa, he was a newlywed native of Raia and an employee of the Military Hospital in the city. He succumbed to his injury 10 days later.

After a few years, the clapper of the bell dislodged, killing a man, and a smaller bell fell off from the tower. In 2018, a similar tragedy was averted, thanks to the alertness of parishioners Samuel D’Silva and John Fernandes. They repaired the sagging bell shaft and the broken clapper of the main bell. ‘We researched a lot before we started on this. We examined many bell towers, particularly that of the Cathedral See,’ said fabricator Silva.

The repairs took three years. Mechanical engineer Fernandes recalled the crucial inputs received from metallurgical engineer Edgar Remedios, fabricators Maria Enterprises of Pilerne, carpenter Mahesh Vishwakarma of Panjim, Rohan Parab of Mahalaxmi Workshop, Bethora, and welding technologist Ramesh Arolkar of Poona.

Fernandes said, ‘It is a joy that with their wholehearted cooperation we were able to complete the work with precision and without any casualty, by November 2021, under the banner of the Immaculate Conception.’ The works were undertaken during the tenure of parish priest Fr Walter de Sá and Confrarias president Pedrito Fernandes.

Appreciating the iconic heritage bell, parish priest Fr Cipriano da Silva, opines that the bell has aged as gracefully as the church building itself. ‘Majestically perched almost at the pinnacle of the frontispiece, the old bell not only adds beauty but also increases the faith and fervour of the people,’ he added.

Reflecting on the bell, Fr Haston Fernandes, assistant parish priest, said, ‘A church bell is not just metal clanging to remind the faithful about an oncoming liturgical ceremony. As per the old rite, its ringing has an exorcising power over the parish. We sometimes take our bells for granted. I hope our church bell awakens us spiritually as to what it has been doing every day.’

Panjim’s white icon is now hemmed in by high-rises, yet it remains the city’s best-known landmark. People also connect with its stately bell, which has a calming effect in the midst of an oppressive soundscape. The bell is a constant invitation to heed God’s voice.

Pic credits: 1, 2 - Oscar de Noronha; 3, 4, 5 - Samuel D'Silva

This article first appeared in Herald Cafe, 30 November 2025, p. 1, and, with a few additions, at https://www.heraldgoa.in/cafe/panjim-church-bell-strikes-150/455647/ on 1 December 2025.

Goencheo Mhonn'neo | Adágios Goeses - 12

Segue a duo-décima lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

| Concani | Tradução literal | Tradução livre

|

| Vagachyá tonddantuló suttunn, xinvanchyá tonddant poddló.

Vagachea tonddantlo suttun, xinvachea tonddant poddlo.

Ximêr moddém. Ximer moddem.

Ghâr firtokúsh vanché firtat. Ghor firtokuch vanxe firtat.

|

Escapando da boca do tigre, livre e são, caiu na de leão.

Salvo do mal menor, foi cair no maior. Colocar o cadáver no limite. (Processo torto; para se não saber a que paróquia pertence o morto.) Não decidir a questão; estar entre dois partidos, perplexo, em vacilação.

Quando, pelo aluimento Se vira uma casa, vira-se também o seu vigamento. Na adversidade, até amigos procedem como os inimigos. |

[1] Cf. um-décima lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 34, maio-junho de 2025, p. 52.

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 37, Set-Out 2025, p. 46

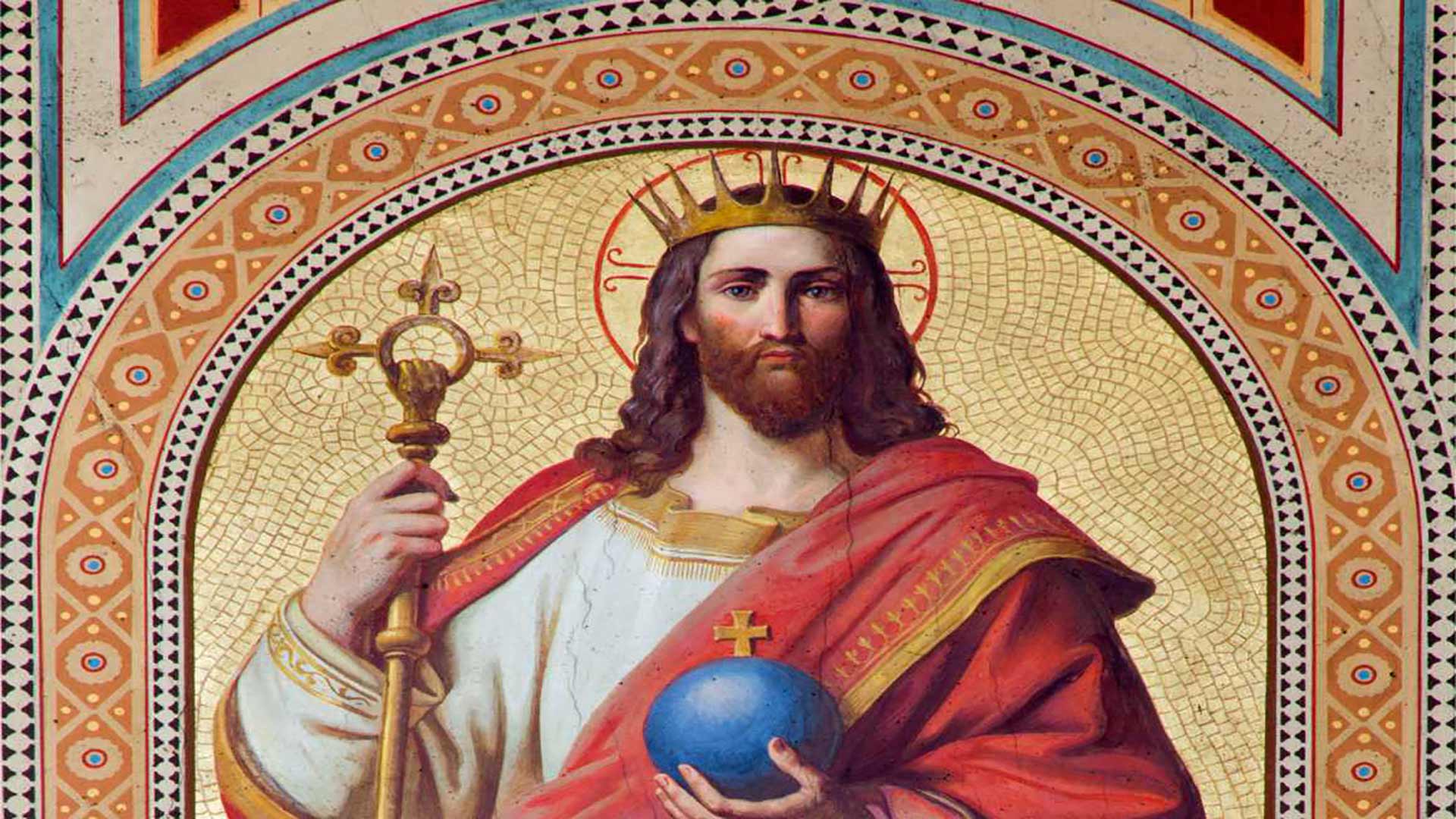

‘Christ is King’: do we really mean it?

The last Sunday of the liturgical year is dedicated to Christ the King. Even if He is not acknowledged in the secular world today, we can be sure that He will be sooner or later. Meanwhile, within the Church, it is for us to proclaim Him from the rooftops. But do we do it?

Sad to say, nowadays, even in the highest echelons of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, many bend over backwards to please the world. As if to justify such an approach, they say that we must move with the world. To them, G. K. Chesterton has fittingly said, ‘We do not want a Church that will move with the world. We want a church that will move the world.’ This is a self-respectful, dignified, spirited, and inspiring position.

In the First Reading (2 Sam 5: 1-3), we see how the tribes of Israel pleaded with David to lead them as their king. Saul, the first king of Israel, had left the kingdom in a shambles. After his death in battle, the kingdom split between his successor, Ish-bosheth, and David. After a civil war, David defeated Ish-bosheth and unified the northern kingdom of Israel with the southern kingdom of Judah, establishing a new united monarchy.

David instructed his successor, Solomon, to follow God’s law at all times and be sure of success. Despite his reign beginning with prosperity, wisdom, and major construction projects such as the First Temple, Solomon’s later years were marked by excessive taxation and the introduction of idolatry through his many foreign wives. This led to unrest and the eventual division of the kingdom after his death.

Idolatry is a nuisance of our times as well. Do you remember the glorification of Pachamama (a goddess of Earth and fertility from Andean cultures, primarily Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and northern Argentina) during the Amazon Synod at the Vatican? Catholics around the world were indignant not only to see the pagan statues present in various ceremonies but also to see the then Pope bless one of them. He was also present when the statue was carried into the synod hall at the beginning of the Synod, accompanied again with pagan rituals.[1] While top prelates looked on, thankfully, three cardinals and three bishops separately voiced opposition to paganism in the church ceremonies.[2]

The Gospel (Lk 23: 35-43) reminds us that when Our Lord was on the Cross, the people stood watching, and the rulers derided Him, saying: ‘He saved others; let him save himself, if he be Christ, the elect of God.’ When we bow to other gods and seek their favour, not only are we complicit in idolatry, it is a clear sign that we do not believe that Christ alone can save us. The soldiers also mocked Him, and one of the robbers blasphemed Him, as some of us do today. In such situations, we would do well to say to the perpetrators of the crime, ‘Neither dost thou fear God...?'

However, it takes faith to say those words, and faith to believe! Perhaps we would ask God for pardon at the hour of our death, as the robber did by saying ‘Lord, remember me when thou shalt come into thy kingdom.’ But then, will we have the time or the occasion to repent? Therefore, it is better to give up wrongful ways while it is still time. Let us take courage and call them out, no matter who or what. We shall have done our duty, and when our time comes, Jesus will say to us, as He said to the repentant robber: ‘Amen I say to thee, this day thou shalt be with me in Paradise.’

In this matter, no one could be more seasoned than St. Paul. In the Second Reading (Col 1: 12-20), he who weathered many storms tells us of Christ’s supremacy: all things in heaven and on earth were created through Him and for Him. God the Father has made us worthy to be partakers of the company of the saints in light. He has delivered us from the power of darkness and has translated us into the kingdom of the Son of His love, who is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature.

Do we still dare not acknowledge Him as King? Are we going to exchange eternal salvation for petty trinkets here on earth? Those who have the responsibility to lead the faithful will have to give an account of themselves, and so will the faithful, who can tell the difference between true and false, right and wrong, and good and bad. So, let us hasten not only to proclaim but also show through our actions that Christ is King.

Banner: https://www.usccb.org/Christ-the-King-2024-novena

[1] https://www.corrispondenzaromana.it/international-news/six-cardinals-and-bishops-who-condemned-pagan-pachamama-rituals-at-vatican/

[2] Cardinal Raymond Leo Burke from USA; Cardinal Robert Sarah from Guinea; Cardinal Gerhard Müller, former Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith; Bishop Joseph Strickland of USA; Bishop Athanasius Schneider of Kazakhstan, and Bishop Peter Chukwu of Nigeria.

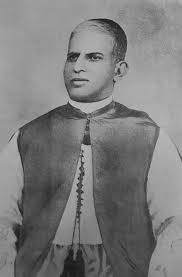

Mariano Saldanha: um distinto académico goês

Ao conhecer um grande senhor nascido apenas duas décadas após a Revolta dos Cipaios[1], senti a corrente do passado transitar suavemente para o presente. Esse notável goês, que emigrara para Portugal no ano da Grande Depressão, passou os anos de jubilado em Goa e faleceu após Portugal ter reconhecido formalmente a conquista indiana da sua terra natal. Era quase centenário, porém, isso é o mínimo que se pode dizer de alguém que marcou na história de várias outras maneiras.

Primeiros anos

Mariano José Luís de Gonzaga Saldanha, vulgo Mariano Saldanha, nasceu em 21 de Junho de 1878, filho de Luís José António Assis André de Saldanha, de Ucassaim, e de Ana Joaquina Ermelinda da Pureza e Dias, de Socorro. Era médico que se fez indologista e pesquisou a história, língua, literatura e cultura indo-portuguesas. Era sobrinho de dois irmãos padres, Joaquim José Santana de Saldanha, fundador de uma escola na aldeia, e de Manuel José Gabriel de Saldanha, professor do Liceu de Nova Goa e autor da clássica História de Goa[2], em dois volumes.

Em 1905, Mariano Saldanha formou-se em medicina e farmácia pela antiga Escola Médico-Cirúrgica de Goa e depois trabalhou como médico em Goa e a bordo de navios. Entretanto, sentindo-se vocacionado para o estudo de línguas indianas, aprendeu o sânscrito com monsenhor Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, na Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, e frequentou cursos na Escola Colonial. Na época de Herculano em Portugal, e de Cunha Rivara e de Dalgado em Goa, não era raro um profissional do ramo da ciência interessar-se pelas humanidades; contudo, no caso de Mariano Saldanha, a mudança foi total.

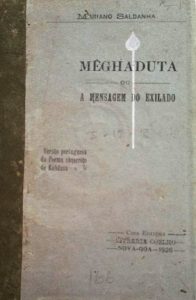

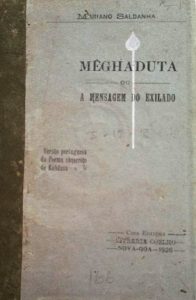

Em 1915, foi nomeado professor de marata e sânscrito no referido Liceu. No ano seguinte, publicou O Curso de Sânscrito Clássico,[3] que compreendia o seu discurso inaugural sobre a importância desta língua e os documentos relativos à criação do curso em questão. Em 1926, traduziu o poema Mêghaduta, ou a mensagem do exilado,[4] de Kalidasa, poeta e dramaturgo da Índia antiga, anotado, prefaciado e acompanhado do original sânscrito.

Docente em Lisboa

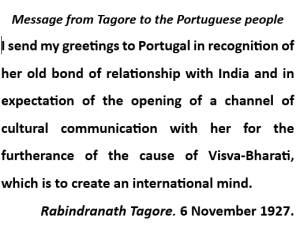

Em 1929, Mariano Saldanha mudou-se para Lisboa, agora como professor de sânscrito na sua alma mater, ocupando o lugar que ficara vago desde a morte de monsenhor Dalgado em 1922. Trazia ao povo português uma mensagem de amizade de Rabindranath Tagore, Prémio Nobel da Literatura, quem visitara em Shanti-Niketan em 1927, atraído pela ideia de harmonizar a cultura indiana antiga com ideias internacionais. Após a morte do grande poeta e pedagogo bengalês, Saldanha recordou o encontro na memória que publicou com o título “O Poeta de uma Universidade e a Universidade de um Poeta”[5].

Em 1946, Mariano Saldanha era nomeado subdirector do Instituto de Línguas Africanas e Orientais da Escola Superior Colonial, onde veio a leccionar o sânscrito e o concani até se aposentar em 1948. Publicou a Ultima Lectio[6], e depois da jubilação, um manual, Iniciação na Língua Concani, “especialmente organizado para o ensino, de carácter prático, da língua concani” na referida Escola.[7]

Voltou a Goa em 1950, onde permaneceu cerca de quatro anos, tendo sido depois convidado pelo Governo da Metrópole a participar na elaboração de um projecto de ensino público em concani, para Goa, e na transmissão de programas radiofónicos nessa língua para a diáspora goesa na África Oriental Britânica e no Golfo Pérsico.[8]

Aproveitou a oportunidade para continuar as suas pesquisas na capital.

Concanista de renome

Além de docente, Mariano Saldanha foi um investigador de renome, principalmente como concanista, ou seja, na ‘Concanologia’[9]. No 50.º aniversário da morte do ilustre estudioso, cumpre recordar o seu precioso contributo para os estudos da Língua Concani, que tanto amou e pela qual tantos esforços despendeu.

Dedicou-se sobremaneira à pesquisa fundamental da língua da sua terra natal. Visitou bibliotecas, arquivos e museus de Goa, Lisboa, Évora, Braga, Paris, Londres e Roma, vasculhando livros e manuscritos, à procura da mais pequena pista. Escreveu exuberantemente, com artigos em revistas científicas e em jornais.

Em 1936, escreveu uma valiosa história da gramática concani, no Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, que se destacou também pelo pioneirismo.[10] Em 1943, escreveu uma série de artigos sobre “Questões do Concani”, no Heraldo, um diário panginense.[11]

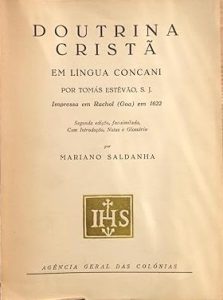

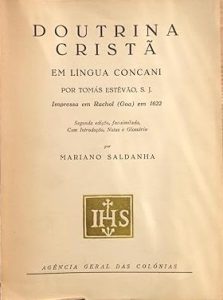

Em 1945, publicou a 2.a edição, fac-similada, com introdução, notas e glossário, de Doutrina cristã em língua concani (1622)[12], de Thomas Stephens, missionário jesuíta britânico, que foi o primeiro inglês a chegar ao subcontinente indiano e pioneiro no estudo das línguas indianas.

Em 1950, descobriu três códices na Biblioteca Pública de Braga, a saber, n.os 771, 772 e 773. As primeiras duas relatam, em concani, histórias tiradas das epopeias indianas, respectivamente, o Mahabharata e o Ramaiana; o último contém três dezenas de poemas em marata, também da mesma fonte; e todos eles escritos em caracteres romanos.[13] Prontamente informou outros interessados, inclusive um dos seus dissidentes ideológicos, A. K. Priolkar.[14]

Cultura goesa

Mariano Saldanha tinha consciência da rara singularidade de Goa, no meio do vasto subcontinente indiano, como síntese cultural do Oriente e Ocidente e detentora de um modo de vida próprio. Por isso, em 1947, mal que sentiu soprar os ventos da mudança política, o seu profundo amor à terra natal levou-o a dar um sinal de alerta.

Fê-lo primeiro por meio de um ensaio intitulado “A lusitanização de Goa”, na revista Rumo.[15] Em Goa, a Repartição de Estatística e Informação reimprimiu-o,[16] e em Portugal, a Agência-Geral do Ultramar traduziu-o em grande parte para o livro Portugal Overseas and the Question of Goa[17]. Ainda hoje é muito citado.

O douto professor sentiu-se feliz como presidente da 5.a edição do Konkani Porixod, conferência a nível pan-indiano, realizada em Bombaim, em 1952. O seu «Odhiokxachem Bhaxonn»[18], ou discurso presidencial, foi publicado em caracteres latinos, que recomendava para o concani moderno. Nessa ocasião afirmou que o concani é uma língua independente do marata e que deveria ser o veículo de instrução primária em Goa.

A propósito do referido Porixod, deu largas ao seu conceito histórico da língua concani, na memória intitulada “A língua concani: as suas conferências e a acção portuguesa na sua cultura”, publicada no Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama.[19] Duas décadas antes abordara esse tema no IX Congresso Provincial de Goa[20].

Nesta fase da vida, expressou-se também sobre a música ocidental em Goa[21]; sobre a imprensa seiscentista aí estabelecida, pioneira na Ásia[22]; e sobre a literatura purânica cristã[23], frisando sempre a identidade marcante de Goa.

Os seus trabalhos retratam-no como investigador escrupuloso, crítico exigente e polemista temível.[24]

Últimos anos

Em 1958, Mariano Saldanha voltou de vez ao solar da família e à aldeia natal que ainda mantinha o charme rústico de outrora. Aceitou como facto consumado o desfecho que teve o conhecido Caso de Goa e, em 1967, regozijou-se com o resultado do Opinion Poll, ou referendo. Infelizmente, na vida particular, foi, por um lado, vítima das leis de expropriação do período pós-1961, e por outro, privado das suas últimas economias que havia confiado ao seu antigo empregado em Portugal. Para agravar, saiu prejudicado na reforma devido ao novo contexto político.

Apesar disso, a vida continuou. Com excepção da gota e da surdez, gozava de boa saúde e manteve-se lúcido até ao fim da vida. Escrevia para os órgãos públicos, recebia visitas e aceitava convites para reuniões académicas e outras. E ainda na provecta idade, costumava celebrar o seu aniversário, cercado de familiares e amigos da velha-guarda.

Manuel Leitão, filho do seu antigo cuidador Francisco, recorda-o como um católico devoto, de coração bondoso e leitor assíduo de jornais da língua portuguesa (O Heraldo e A Vida), concani (Vauraddeancho Ixtt, Sot e Uzvadd) e marata (Gomantak), de entre os publicados em Goa. Mantinha relações com os respectivos directores e colaboradores, e no interesse destes, e ansioso por estabelecer padrões elevados, corria com tinta vermelha os jornais concani.

O erudito era consultado em assuntos relativos a Goa e ao concani. Não admira que a sua rica biblioteca com centenas de livros, microfilmes e manuscritos, tivesse atraído jornalistas e investigadores, entre os quais Carmo Azevedo, que, escrevendo no mensário Goa Today, o apelidou de “enciclopédia viva de coisas goesas”[25], bem como os activistas do Konkani Bhasha Mandal. A família doou o acervo ao Xavier Centre of Historical Research, de Goa.

Apesar das cãs, o bom e velho solteirão era paciente com os jovens. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho deleitava-se com o saber e a sagacidade do seu tio-avô. Graças à sua prodigiosa memória, este contava-lhe prontamente histórias sobre Akbar, Xivaji e outros vultos indianos, que faziam parte dos currículos escolares do pós-1961; e ela incluía-as nas suas provas.

Tive eu, como menino de 6 anos, o meu primeiro encontro com o professor já então nonagenário. No Hospital do Asilo, em Mapuçá, havia ele discursado e descerrado o busto do Dr. Ernesto Borges, seu sobrinho-neto, oncologista de renome mundial e que cedo pagou o tributo à morte. Foi um momento emocionante. Eu acompanhava a minha tia Maria Zita da Veiga, que havia experimentado o seu toque curativo. Após a cerimónia, perguntaram ao professor se se importaria de esperar um pouco mais pelo transporte para casa. Impressionou-me a sua resposta: “Claro que me importo”. E logo a gargalhada que se seguiu desdizia tudo….

É impossível dizer tudo de uma vez sobre Mariano Saldanha, distinto académico goês que muito honrou a sua terra. Faleceu em 23 de Outubro, mês Mariano, do ano de 1975, quase desconhecido das novas gerações e um tanto esquecido pelas velhas. Deve ser, porém, evocado com gratidão e estudado com atenção, tal como todos os vultos da nossa terra, para que se facilite assim uma transição harmoniosa do passado para o presente.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 37, Novembro-Dezembro 2025, pp. 33-37)

Referências

[1] Revolta armada, realizada entre os anos de 1857 e 1859, em oposição ao domínio britânico, a qual de Meerut passou para Delhi, Kanpur e Lucknow, cidades no norte da Índia.

[2] 2.ª edição. Nova Goa: Edição da Livraria Coelho, 1925-26. A primeira edição intitulava-se Resumo da HIstória de Goa, publicada em 1898, em um único volume.

[3] Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1916.

[4] Nova Goa: Casa Editora Livraria Coelho, 1926.

[5] Revista de Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa, N.º X, 1943, pp. 57-77.

[6] Anuário da Escola Superior Colonial, Ano XXIX, 1947-48, Lisboa, 1948. Também nos Estudos Coloniais, Lisboa, Vol. I, 1948-49.

[7] Parte I: Noções Gramaticais. Lisboa: 1950. Não consta que tenha saído a Parte II.

[8] “Mariano Saldanha: a centenary tribute”, de Teotónio R. de Souza, in Indica, Vol. 15, N.º 2, Setembro de 1978, pp. 135-138.

[9] Termo por ele cunhado para se referir às “publicações relativas ao concani”, veja-se Monsenhor Dalgado. Esboço bio-bibliográfico. Lisboa: 1933, p. 11.

[10] "História da Gramática Concani," Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 8 (1935–37), pp. 715-735.

[11] Heraldo, de 14, 16, 24, e 30 de Março de 1943.

[12] Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1945.

[13] Os códices ora encontram-se na biblioteca da Universidade do Minho, veja-se The Old Konkani Bhārata. Volume 1: Introduction, de Rocky Miranda (Margão: Asmitai Pratishthan, 2019), p. xi.

[14] Mais tarde, Panduronga Pissurlencar, José Pereira, António Pereira, Lourdino Rodrigues, Rocky Miranda e outros serviram-se dos mesmos códices para os seus trabalhos de pesquisa.

[15] Rumo, Revista de Cultura Portuguesa. Ano 1, Agosto e Setembro, 1946, pp 343-366

[16] No. 6 da série da Colecção de Divulgação e Cultura.

[17] Lisboa: Agência-Geral do Ultramar, s.d., pp 41-58

[18] Konknni Porixod. Panchvi Boska. 1952. Odhiokx: Dr. Mariano Saldanha, Hachem Bhaxonn. (Mumboi: Fr Napoleon Silveira, 1952) É o único texto seu expresso inteiramente em concani.

[19] N.o 71, 1953.

[20] Congresso Provincial da Índia Portuguesa (Nono), Nova Goa: Tip. Bragança, 1931.

[21] “A cultura da música europeia em Goa”, Separata da Revista do Instituto Superior de Estudos Ultramarinos, Vol. VI (1956).

[22] “A primeira imprensa em Goa”, Separata do Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama, N.º 73, 1956.

[23] “A literatura purânica cristã e os respectivos problemas linguísticos e bibliográficos”, Separata do Boletim do Instituto Vasco da Gama, N.º 82, 1961.

[24] Veja-se As investigações de um gramático (Lisboa: Tip. Carmona, 1933), em que escalpela a obra Elementos gramaticais da língua concani (Lisboa: Agência Geral das Colónias, 1929), de José de S. Rita e Sousa, antigo professor da Escola Superior Colonial; e Aditamentos e correcções à monografia O Livro e o Jornal em Goa (Bastorá: Tip. Rangel, 1936) e Ainda a monografia O Livro e o Jornal em Goa (Bastorá: Tip. Rangel, 1938), nas quais interpela o professor liceal Leão Crisóstomo Fernandes.

[25] “A Date with Dr. Mariano Saldanha”, in Goa Today, p. 13.

Consecrating the living temple

Just like the Feast of All Saints that fell on the 31st Sunday in Ordinary Time had readings proper to that particular observance, the Feast of the Dedication of the Lateran Basilica in Rome, which falls today, the 32nd Sunday in Ordinary Time, has a unique set of readings, not part of the regular cycle for Ordinary Time.

What, then, is special about 9 November? On this day in the year 324 A.D., the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran in Rome was consecrated as the official cathedral of the Pope, the Bishop of Rome. The first major basilica built in the Roman Empire was granted the status of ‘Mother and Head of All Churches in the City and of the World’ (omnium urbis et orbis ecclesiarum mater et caput).

In 1724, Pope Benedict XIII ordered the worldwide observance of the date. He looked at the basilica as a symbol of unity and strength between the Catholics and the Holy See. The feast also connects to the biblical idea that the church building symbolises the people themselves, and each believer is a ‘house of God’ where the Holy Spirit dwells.

Today’s celebration is also a reminder of the history of Christianity, particularly the freedom gained through the Edict of Milan. This was an agreement issued by Roman Emperors Constantine I and Licinius in 313 CE, granting religious tolerance throughout the Roman Empire. It marked a major turning point, as Christianity went from a persecuted faith to a legally recognised and protected religion.

The readings of the day focus on God’s temple. In the First Reading (Ezek 47: 1-2, 8-9, 12), the ‘east’ seems like the operative word, symbolising new beginnings, divinity, and hope. We look to the east for the morning sun’s rays that can well symbolise Jesus, the Light of the World. The water that ‘flows into the eastern district down upon the Arabah’ could refer to Jesus, the Living Water. This text is also read on Tuesday of the fourth week of Lent.

Similarly, the Gospel (Jn 2: 13-22), which portrays the first Pasch in Jesus’ ministry, is also aptly used for the third Sunday of Lent (year B). The fact that He had not begun His public ministry did not prevent Him from showing zeal for His Father’s House. Here, not only did merchants sell their wares but also the chief priests sold some people’s offerings. With a whip of cords, Jesus drove out those who sat there selling oxen, sheep, and doves, spilled the coins of the money changers, and overturned their tables. His disciples recalled the words of Scripture, ‘Zeal for your house will consume me.’ (Ps 69)

Jesus did not go unchallenged by the Jews. They wished to know on what authority He was acting. That is when we hear Jesus’ memorable words, enigmatic when they were first heard: ‘Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it up.’ How could that be? The Jews retorted, ‘This temple has been under construction for forty-six years, and you will raise it up in three days?’

How unperceptive of them! We could count ourselves in their number. They took Jesus literally, thinking that he was referring to the building, whereas Jesus was speaking about the temple of his Body. Thus, when He was raised from the dead, His disciples remembered that He had said this, and they came to believe the Scripture and the words spoken by Him.

We too sometimes look at our church as a mere building, don’t we? Therefore, in the Second Reading (1 Cor 3: 9c-11, 16-17), St. Paul reminds us that you and I are God’s building—we are the living church. Our ancestors in the faith built it for us in Goa, just as the Apostle built it for the Gentiles, and what they have built we must not break asunder. How wise, therefore, it is to consecrate our homes to God; each of them is a domestic church.

On the other hand, while we think we are building upon it, ‘each one must be careful how he builds upon it, for no one can lay a foundation other than the one that is there, namely, Jesus Christ.’ This applies as much to the Popes and bishops of the world as it does to each of us.

Finally, we believe that the spirit is more important than the body. But more than that, we must never forget that the Spirit of God dwells in us, making us holy temples of God. Hence, if anyone, including ourselves, destroys God’s temple, God will destroy that person. The gates of Hell are open to receive such persons. Sad, but true; something we see when we reflect on the Last Things, as we did last Sunday.

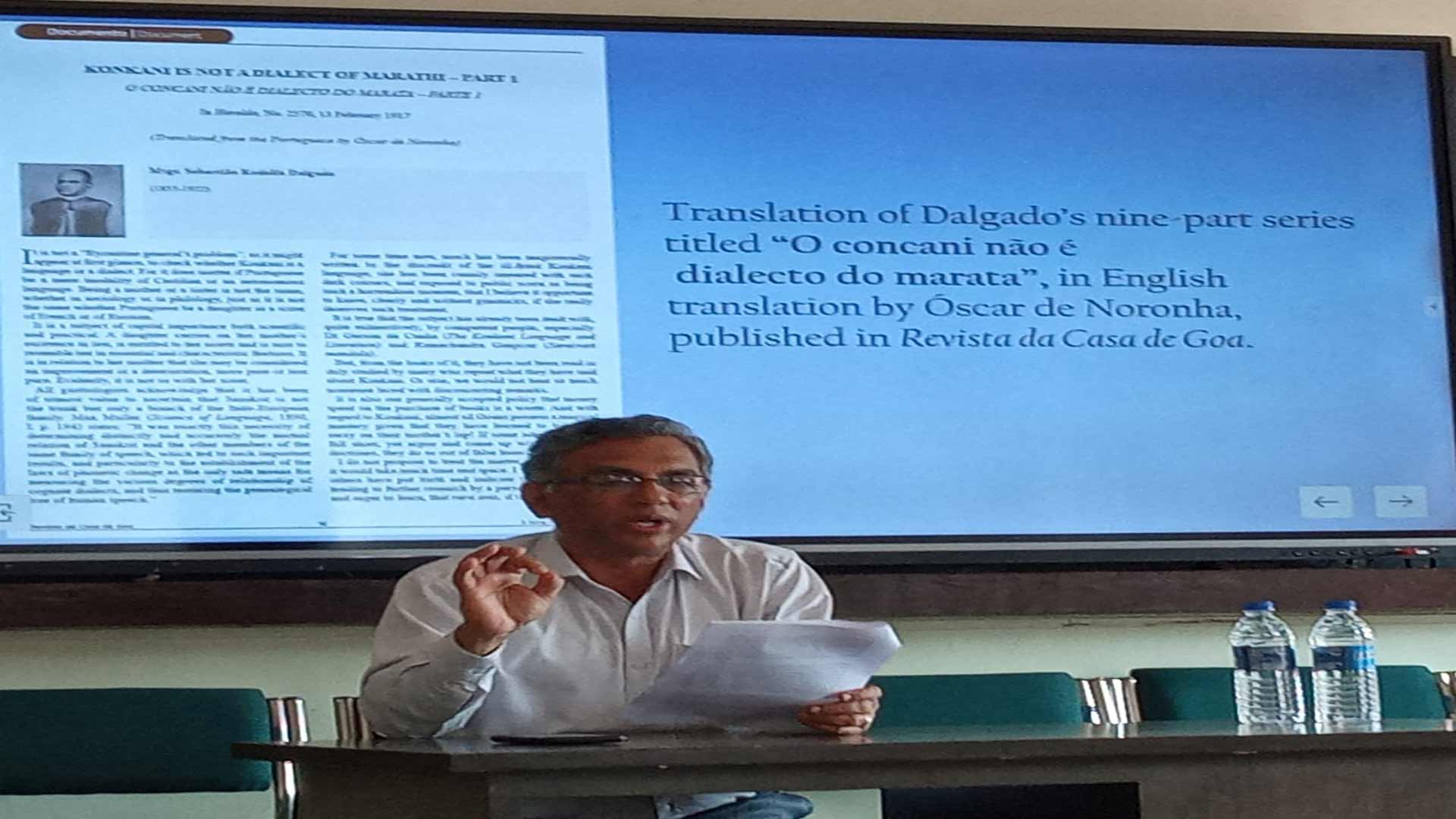

Konkani before and after Dalgado

In 1917, Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, an internationally renowned Goan linguist, forever changed the course of the Konkani-Marathi controversy. In a nine-part series titled “O concani não é dialecto do marata” (‘Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi’), published in the Panjim daily Heraldo, he analysed the linguistic and grammatical characteristics of Konkani, demonstrating its identity as distinct from that of Marathi. But, then, what events led Mgr. Dalgado to write the series?

Fabricated controversy

The Konkani-Marathi controversy is not as ancient as it might seem; it is a nineteenth-century fabrication. Konkani, which, like Marathi, evolved from Prakrit, began to make rapid strides in the linguistic, lexicographic, and literary fields, thanks to the ingenuity of European missionaries in sixteenth-century Goa. It is another matter that their interest began to wane, and indifference turned into state hostility, to some extent, at least on paper. This brought the first modern literary period of Konkani literature to an inglorious end.

In the eighteenth century, literary production in Goa was conspicuous by its absence, due to the shutdown of the printing press. As a result, not only did Konkani get relegated to the background, but Goa itself became a backwater. Even so, there was not a doubt about Konkani’s linguistic status until the year 1807, when John Leyden dubbed it a dialect of Marathi. His ideas began to gain currency in British India. When those echoes reached Portuguese India, Konkani was excluded from the curriculum of the first state-owned schools set up in 1831. By now, in the new Liberal regime, it suited Goan Catholic elite to adopt Portuguese as their cultural language, while the Hindu elite continued to seek refuge in Marathi and turned to Portuguese in the following century.

Meanwhile, in 1858, J. H. da Cunha Rivara’s famous essay on the Konkani language (Ensaio histórico da língua concani) decried Goa’s contempt of its native language and defended its dignity. His realisation was perhaps a byproduct of a new Orientalist consciousness, which prized the rediscovery of indigenous languages. But alas, it is Marathi and not Konkani that drew the benefit. In 1869, at the behest of Goa’s official translator Suriagy Ananda Rao, the state government banned the use of Konkani, while Marathi ruled the roost at the Panjim Lyceum.

A decade later, when R. G. Bhandarkar in Bombay reiterated Konkani’s dialect status (cf. Wilson Philological Lectures, 1877, a series of seven lectures on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages), scholars favouring the dialect theory slightly outnumbered those favouring the language theory. But a fitting reply awaited Bhandarkar in 1881, when José Gerson da Cunha systematised and coordinated the arguments of the language theory in his Konkani Language and Literature. Nonetheless, in 1905, the Linguistic Survey of India, published by the British Government, buttressed the dialect myth.

Divided Goa

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

The case of Konkani was quietly and insidiously growing into a big problem. By the beginning of the twentieth century, linguistic theories backed by the British colonial administration in India seemed at odds with those articulated in Portuguese India. Curiously, on both sides of the Western Ghats, the foreign element seemed more vocal than the native educated class that patronised but did not write in the vernacular. That was also a time when the Catholic masses in Bombay created the tiatr and the Konkani-language press; for their part, the Goan Hindu Brahmins, published in Marathi but failed to construct an identity, as their Catholic counterparts were doing through Konkani. Interestingly, in 1901, Poona-based Goan writer Eduardo Bruno de Souza, modified the Roman alphabet for use by Konkani, calling it the ‘Marian alphabet’.

While the Konkani movement was thus gaining momentum within the community in Bombay, back in Goa, Thomaz de Aquino Mourão Garcez Palha and Fernando Leal, two mestiços (persons of mixed blood, Portuguese and Goan), who had probably caught the Orientalist bug, began a crusade for the “resurrection of Konkani”. They were supported mostly by members of the Goan Catholic elite.

As regards the Hindu elite, in 1916, when the ayurvedic physician Dada Vaidya (Ramachondra Panduronga Vaidya) spoke in Konkani at Goa’s first Provincial Congress, Marathi writer Xamba Suriarao Sardesai shouted him down and followed it up with a two-part article disparaging the Konkani movement. The division of Goan society was complete, not only between educated Christians and Hindus, but also within the Hindu community.

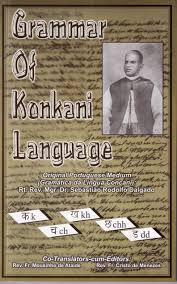

By February 1917, therefore, the stage was set for Dalgado’s intervention from distant Lisbon. The tireless Goan Catholic missionary was now on a mission to prove Konkani’s credentials as a language. He had published a Konkani-Portuguese dictionary in Bombay (1893), and a Portuguese-Konkani dictionary in Lisbon (1905), both of which used the Devanagari and Roman scripts. The university professor and Fellow of the Portuguese Academy of Sciences was an authority on the influence of Portuguese on Asian languages, and his thoughts kept returning to Konkani. Significantly, his last unpublished work was a Konkani Grammar, which Fr Mousinho de Ataíde translated into English in Dalgado’s death centenary year, 2022.

Decisive entry

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s authoritative voice in Heraldo infused the Konkani camp with a new confidence, helping to put many issues to rest. But alas, his articles remained unread by the non-Portuguese speaking majority who could have profited by it. Hoping to right that historical wrong and pay homage to that rare scholar, I had the opportunity to translate his text into English in his death centenary year. The series was later published in the Lisbon-based online magazine Revista da Casa de Goa. (See this blog https://www.oscardenoronha.com/2023/09/26/konkani-is-not-a-dialect-of-marathi-1/ and ff)

Dalgado’s entry was decisive. It was a watershed moment in the history of Konkani Studies. Portuguese-language newspapers in Goa as well as bilingual papers in Bombay began to comment on Dalgado’s efforts in the field. After him, Jules Bloch showed how distinct Marathi was from Konkani; S. M. Katre paralleled Bloch’s book by writing The Formation of Konkani, and together with V. P. Chavan, helped further Konkani’s position as a separate language.

Varde Valaulikar’s writings continued Dalgado’s work of demonstrating Konkani’s individuality. Curiously, Shenoi Goembab began by writing in Marathi, and after switching to Konkani, first wrote in the Roman script. Seven of his twenty-nine books are in the Roman script. In fact, there was no Konkani worth the name in the Devanagari script in Bombay, and much less in Goa.

Perhaps Dalgado and Valaulikar never met or exchanged correspondence, but they shared the same vision. Valaulikar, who knew Portuguese, must have read Dalgado’s rejoinder to Xamba Sardesai. While Valaulikar carried out a literary crusade in Bombay, Dalgado’s academic legacy was kept alive by his pupil Mariano Saldanha in Lisbon. Dalgado died in 1922, and Shenoi Goembab in 1946. In 1952, Mariano Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth All-India Konkani Porixod held there. As a votary of the Roman script, Saldanha’s address was printed in the Roman script.

By the 1950s, the demand for linguistic states had gained significant momentum, leading to the creation of the Telugu-speaking Andhra out of the State of Madras. Much earlier, the Indian National Congress had organised its provincial committees along linguistic zones, signalling an early form of the concept. Dalgado and Valaulikar’s vision of Konkani in the Devanagari script dovetailed into that concept, whereas Saldanha envisioned the Roman script for Konkani in Goa. It did not materialise in the post-1961 scenario, for obvious reasons.

Goa post-1961

It was an entirely new ballgame after Goa got into the Indian Union. Maharashtra had laid claim to Goa, deeming Konkani a dialect of Marathi. The Goan elite, which was once divided between Portuguese and Marathi, leaving Konkani to fend for herself, now realised that only Konkani could help preserve their identity. It was a David and Goliath situation, in which Konkani won because the language was on the people’s lips and nobody could take it away. Its literature was perhaps not on a par with best in the country, but it had a strong foundation built by Dalgado and Valaulikar.

Hence, while Valaulikar is regarded as the Father of Modern Konkani Literature, Father Dalgado, by his fundamental contribution to the development of the language, ought to be regarded as the Grand Father (pun intended) of Modern Konkani. Their impact was felt at the time of the Opinion Poll and when Sahitya Akademi recognised Konkani as a literary language; when Goa achieved statehood and Konkani became the state language, and when Konkani was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

Thereafter, Konkani came into a privileged position, as never before. It would seem like a time to consolidate had arrived. For instance, in the Konkani world beyond Goa, it would pay dividends to make the most of the multi-script situation; but that was not to be. In Goa, the issue of script remains Konkani’s Achilles heel. The sooner this is resolved the better, to ensure the interests of all the user communities; their wellbeing is bound to produce positive results for the popularity and expansion of the language. The more the scripts the better.

Case for the Roman script

It is also a time for some reflection. Has the shared legacy created by Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab been put to creative use? It would be interesting to consider what their response would be to our globalised world. How would they respond to demands for recognition of the Roman script in today’s multilingual and multicultural world? Would they consider it an opportunity to woo back Konkani speakers at home and in the diaspora, and to win new speakers from across the big wide world? Would they appreciate the possibility of Konkani finally becoming at once a means of communication and identity marker?

After all, living languages are dynamic, and no script is perfect. Goykanadi was the earliest known native script that Konkani used, before it was supplanted by others. Similarly, the earliest known script for the English language was the Anglo-Saxon futhorc. From the seventh century onwards, the Latin alphabet began to replace the futhorc, though they coexisted for a time in England.

It is the same in India. The Latin or Roman script is not to be considered foreign; it is as Indian as the English language in the country. If the English language can be made official, so can the Roman script, or any other for that matter, if numbers and the volume of work justify it.

Not to let script remain a divisive issue, would Dalgado and Shenoi Goembab, then, consider letting Goa be the first state in the Indian Union to successfully resolve a multi-script situation? Any script that has worked in the past ought to work in the future. This applies to the Roman script as well. Surely, Dalgado’s mission was to save the language over and above the script.

A Distinguished Goan Scholar

After one has met a grand old man born just two decades after the Sepoy’s Mutiny, history cannot but look like a thing of the present. He migrated to Lisbon in the year of the Great Depression. He spent his post-retirement years in Goa and died several months after Portugal formally recognised the Indian takeover of his native land. He was a near-centenarian, but that is the least of his claims. He made history in more ways than one.

Dr. Mariano Saldanha (1878-1975) of Ucassaim was a physician-turned-indologist who studied history, language, literature, and culture. He was the nephew of Fr Gabriel de Saldanha, the author of the classic História de Goa. In 1905, he graduated in medicine and pharmacy from Goa’s iconic medical school. After a few years of professional practice, he left for Portugal to study Sanskrit under Mgr. Dalgado at the University of Lisbon. It was not unusual then for a man of science to show an interest in the humanities, but his was a total switch.

On his return in 1915, he taught Marathi and Sanskrit at the Panjim Lyceum and translated Kalidasa’s Meghaduta into Portuguese. In 1929, he was back in Lisbon, now a professor of Sanskrit at his alma mater. He proudly carried a message of friendship to the Portuguese people from Tagore, whom he visited in Shantiniketan. In 1946, he was appointed as the deputy director of Escola Superior Colonial’s Institute of African and Oriental Languages. He taught Konkani there until his superannuation in 1948.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

Ten years later, he returned to his family home. He enjoyed good health until the very end. His caretaker’s son Manuel Leitão remembers him as a dutiful Catholic with a caring heart. He was a regular reader of Portuguese, Konkani, and Marathi newspapers. Keen to establish high standards, he would red-mark the Konkani papers for the writers’ benefit. It is no wonder that his house became a centre of attraction for Goan journalists and researchers.

On the milestone anniversary of this distinguished scholar, we recall his precious contribution. Mariano Saldanha’s affinity to history and languages was evident from an early age. He pursued fundamental research in the Konkani language in Lisbon. He spent countless hours in libraries, archives, and museums, sifting through books and manuscripts with a scrupulous eye for the smallest clue.

In 1945, Professor Saldanha produced an annotated facsimile edition of Thomas Stephens’ Doutrina cristã em língua concani (Christian doctrine in Konkani, 1622). In 1950, he unearthed sixteenth-century Konkani and Marathi manuscripts in Braga’s public library. The love of truth drove him forward not only to discover but also to share the fruits of his discovery. He did so even with his ideological dissenters, such as A. K. Priolkar.

In 1952, Saldanha was in Bombay as the president of the Fifth Konkani Parishad. Being a strong votary of Konkani in the Roman script, his address was published accordingly. Curiously, this is his only text written in Konkani. When he sensed the political winds of change, he began to emphasise Goa’s distinctiveness in the Indian subcontinent, through its language, Konkani; the Lusitanian influences on its culture; the roots of Western music; its pioneering printing endeavours, and its Christian Puranic literature.

After his death, his family gifted his large book collection to the Xavier Centre of Historical Research. His microfilms and manuscripts show his discipline and patience. He was a member of several academic bodies and published his writings in journals and newspapers. They depict him as a thorough academic researcher, an exacting reviewer, and a formidable polemicist.

However, nothing prevented the good old bachelor from being patient with the youngsters. Maria Helena Saldanha de Santana Godinho told me of how she used to lap up information and pearls of wisdom from her granduncle. While, thanks to his prodigious memory, he recounted stories with ease, she happily fit those anecdotes about Akbar, Shivaji, and other Indian greats, in her school answers.

At age 6, this writer had an unforgettable first encounter with the then-nonagenarian professor. He had unveiled the bust of world-renowned oncologist Dr. Ernest Borges, his grandnephew, at Asilo Hospital, Mapuçá, and addressed the gathering. It was an emotional moment. After the ceremony, the Professor was asked if he would mind a slight delay in his ride home. His stern reply was, ‘Yes, I mind.’ But then, the delayed laughter said it all.

For their part, the citizenry today should mind that the memory of Goan notables is often taken for a ride. They deserve better from our civic, academic, and governmental bodies if we are to achieve a seamless transition from the past into the present.

Banner: Dr Mariano Saldanha delivering the presidential address at the Fifth Konkani Parishad, Bombay, 1952

This article was first published in Herald, Panjim, on Dr Mariano Saldanha's 50th anniversary of death, 23 Oct 2025

The Red Line

Is God someone who takes the fun out of our situation? Two of the three readings of today are indictments of our behaviour, and one prescribes a treatment.

The First Reading (Amos 6: 1.4-7), originally meant for the upper crust of the kingdoms of Judea and Israel,[1] is also a message for all people, whether in Goa or California. In a passage reminiscent of the Woes listed by St Luke, the prophet Amos decries those who only live to eat, drink, and make merry; who ‘lie upon beds of ivory and stretch themselves upon their couches’, and show least concern for their suffering brethren. They are beneficiaries of God’s largesse, yet ‘not grieved over the ruin of Joseph’ (a reference to the ten tribes of Israel with whom Joseph’s name became synonymous).

The Gospel (Lk 16: 19-31) puts it all in a parable that is unique to the Evangelist St Luke. An unnamed rich man who cared for none but himself is tormented in Hell, whereas poor Lazarus (not the one raised to life in John’s Gospel), who was at his mercy on earth, now enjoys the Beatific Vision. It is not an indictment of riches, but of our wretched attitudes. Deposuit potentes: God puts down the mighty from their seats,’[2] or, as Mephistopheles says in Marlowe’s The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus: ‘Fools that will laugh on earth must weep in hell’.

In the midst of it all, the rich man requests God to forewarn his family that Hell is for real: ‘lest they also come into this place of torment’. This was perhaps his only charitable thought, whereas Lazarus (meaning ‘God is my help’ in Hebrew) had the Lord to turn to. Indeed, God is ‘just to those who are oppressed’, ‘who gives bread to the hungry’, ‘who sets prisoners free’, ‘who gives sight to the blind, who raises up those who are bowed down’, ‘who loves the just’, ‘who protects the hungry’, ‘He upholds the widow and orphan but thwarts the path of the wicked’ (cf. today’s Psalm 145: 6-10).

Can God who cares for us be against human enjoyment or amusement? All He asks of us is not to cross the red line between right and wrong. In this sense, every day of our life is a reenactment of the dilemma of the Garden of Eden. Hence, in the Second Reading (1 Tim 6: 11-16) St Paul exhorts us to ‘aim at righteousness, godliness, faith, love, steadfastness, gentleness’—six basic virtues. There is no need for highly wrought theology but for an open heart to understand all of that. Highlighting God’s kingship vis-à-vis the sinful practice of paying tribute to false gods, he urges us to ‘fight the good fight of the faith’ and praise the Lord ‘Who alone has immortality and dwells in unapproachable light.'

In time, we realise that God does not take the fun but the sin out of our situation! He has given us the Scriptures and the Commandments to guide us, and the Sacraments to strengthen and help us to stay within the lines. If we obey, we have everything to gain, if not, everything to lose in the life hereafter. But that’s not all. We have to reach out, show concern for others, and be proactive. Lukewarmness and indifference can be lethal.

Jesus who has said, ‘I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life’ (Jn 14: 6), and ‘I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full’ (Jn 10:10) promises us not temporary but eternal joy as only He can.

Banner: By MOSSOT - Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15941723

[1] After the death of king Solomon, the United Kingdom of Israel, whose capital was Jerusalem, was divided into the northern kingdom (Israel) with Samaria as its capital, and the southern kingdom (Judea) with Jerusalem as the capital.

[2] These words belong to the Blessed Virgin’s Magnificat (Lk 1: 46-55).