Editorial

https://online.fliphtml5.com/bcbho/hzql/#p=1

A nossa minúscula Goa tem o condão de se desdobrar em diversas Goas. Existe a Goa da história e a da contemporaneidade, a Goa geográfica e a dos corações espalhados pelo mundo, a Goa real e a dos nossos sonhos. Há, portanto, diversas Goas. E dentro de cada uma existem engrenagens sociais, económicas, políticas e culturais, sempre a rodar. Quem imagina conhecer as múltiplas Goas vive a fábula indiana dos Cegos e o Elefante.

Todavia, a Revista da Casa de Goa empenha-se por interpretar essas Goas aos leitores. É o caso da presente edição, que começa por falar de Pangim, a poética capital goesa, que dantes teve outros nomes: Nova Goa e Cidade de Goa. O nosso editor associado José Filipe Monteiro conta a interessante história de como, no século XIX, esse modesto bairro da aldeia de Taleigão passou à capital do império português oriental.

Por mera coincidência, outro editor associado, Valentino Viegas, recorda na sua crónica os “doces anos” que viveu em Pangim e em calções percorreu os seus cantos e recantos. E, que maravilha, ficarem de repente, lado a lado, a grande e a pequena história da Índia Portuguesa.

Não é, porém, maravilha a situação que de momento se vive em Goa. Leia-se o artigo intitulado “Será Goa a próxima Ayodhya na Índia?”, de Ivo de Noronha. Goa, aliás, destacada pelo modelo de coexistência pacífica que representa entre as diversas comunidades e pelo seu forte senso de identidade cívica, enfrenta hoje um desafio tão subtil quão insidioso.

Em situações dessas, é tão reconfortante lembrar, como o faz David Pinto, no seu artigo “Globalização em Goa: a contradição asiática”, que essa mesma Goa foi na verdade uma das primeiras sociedades multiculturais e globais de todos os tempos. Acrescenta que, ainda no século XXI, viver em Goa “proporciona uma experiência diferente da de qualquer outra parte da Índia”.

Nota-se esse tipo de pioneirismo na recente nomeação papal do padre jesuíta Richard Anthony D’Souza como Director do Observatório do Vaticano. Prova de como um goês naturalmente se torna cidadão do mundo. Na secção de notícias, damos pormenores dessa honrosa atribuição.

É afinal a sua cultura multissecular que define Goa. Veja-se o caso de Manohar Rai SarDessai, cujo “papel cultural híbrido, ao navegar pelas complexidades da identidade pós-colonial em Goa” é objecto de estudo de Anthony Gomes, no artigo intitulado “Vozes da identidade goesa”. O autor refere-se à literatura mundial que o poeta traduziu para concani; o seu papel no enriquecimento da paisagem literária regional, na promoção do diálogo cultural e na articulação da identidade cultural goesa.

Por sua vez, Júlia Serra foca outro poeta contemporâneo, José Rangel, que reuniu parte da sua obra em Toada da Vida e Outros Poemas. Os seus poemas são de índole diversa: para além do misticismo religioso do Oriente e do dinamismo do Ocidente, há referências a línguas, à procura da identidade, à cultura, à paisagem confrontada com o arranha-céus, à vida nos cabarets; e reflexões sobre o bem e a graça divina, sobre o profano e o religioso, e sobre o amor cantado nas diversas dimensões.

Recuando um pouco, Philomena e Gilbert Lawrence evocam a figura de Luís Vaz de Camões, que em Goa escreveu grande parte d’Os Lusíadas; e traçam paralelos com a vida do eminente Winston Spencer Churchill: foram ambos militares de duas potências coloniais na Ásia.

Ainda hoje continua esse diálogo intercivilizacional iniciado há cinco séculos. Por exemplo, a Fundação Oriente desempenha uma vasta rede de actividades, registadas aqui por Paulo Gomes, seu Delegado em Goa, a oriental Lisboa.

Por outro lado, neste mês, na capital portuguesa, realiza-se LisGoa, um encontro de líderes empresariais de Goa, como destacado no suplemento especial a esta edição.

Não termina ali a panorâmica histórica e cultural de Goa. O conto em concani, ambientado no remoto concelho de Satari, transporta-nos para uma Goa de outrora, dir-se-ia, pré-portuguesa, pois distam muito os costumes desse povo, daqueles que são correntes nas partes cristianizadas de território. “A Árvore de Fruto Amargo”, de Prakash Parienkar, transliterado do concani em caracteres devanagáricos para romanos e traduzido para português pelo editor associado Óscar de Noronha, vai acompanhado também do link do respectivo filme.

Rematamos a apresentação desta edição convidando os leitores à nossa secção de arte. Girish Gujar e Govit Morajkar, respectivamente, em aguarela e pintura, chamam a nossa atenção a dois locais em Goa; o caricaturista Alexyz tece uma crítica aos problemas de Goa contemporânea, enquanto Clarice Vaz e Edgar João apresentam Goa como o eterno idílio.

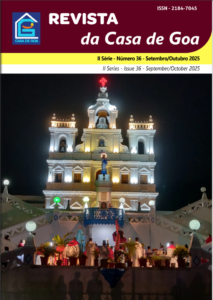

E não vamos sem registar que na capa desta edição temos a Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Imaculada Conceição, o ex-libris da cidade de Pangim; e na contracapa, o link da Global Goan, nossa Revista parceira, cuja leitura calorosamente recomendamos aos Goanófilos.

-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-

Our minuscule Goa has the power to unfold into several Goas. There is the Goa of history and the Goa of contemporary times, the geographical Goa and the Goa of hearts scattered around the world, the real Goa and the Goa of our dreams. There are, therefore, several Goas. And within each of them are social, economic, political and cultural gears that continue to turn. Those who claim to know them all live out the Indian fable of the Blind Men and the Elephant.

Nonetheless, Revista da Casa de Goa strives to interpret these Goas for its readers. The present edition is a case in point. It begins by talking about Panjim, the poetic capital of Goa, which previously had other names: New Goa and City of Goa. Our associate editor José Filipe Monteiro recounts the interesting story of how in the nineteenth century this modest ward of the village of Taleigão grew into the capital of the Portuguese Oriental empire.

Coincidentally, another associate editor, Valentino Viegas, recalls in his column the “sweet years” he spent in Panjim, and in shorts explored its nooks and crannies. And, how wonderful to suddenly see, side by side, the macro and the micro history of Portuguese India.

However, the living situation in Goa is not all that wonderful. Read the article titled ‘Will Goa be India’s next Ayodhya?’, by Ivo de Noronha. In fact, although known as a model of peaceful coexistence among different communities, and for its strong sense of civic identity, Goa faces a challenge that is as subtle as it is insidious.

In situations like these, it is so heartening to recall, as David Pinto does in his article ‘Globalisation in Goa: The Asian contradiction’, that Goa was indeed one of the first multicultural and global societies of all times. He adds that, even in the 21st century, living in Goa ‘provides an experience different from that in any other part of India.’

This type of pioneering spirit shines through Jesuit priest Richard Anthony D’Souza’s recent papal appointment as Director of the Vatican Observatory. A Goan quite naturally becomes a citizen of the world. In the news section we have more details of that honourable selection.

After all, it is Goa’s centuries-old culture that defines it. Look at Manohar Rai SarDessai, whose ‘role as a cultural hybrid navigating the complexities of identity in postcolonial Goa’ is the object of study by Anthony Gomes in his article titled ‘Voices of Goan Identity’. The author refers to the poet’s translations of world literature into Konkani and his role in enriching the regional literary landscape, promoting cultural dialogue, and articulating the Goan cultural identity.

Júlia Serra, for her part, focusses on another contemporary poet, José Rangel, who compiled part of his work in Life’s Refrain and Other Poems. His poems are diverse in nature: in addition to the religious mysticism of the East and the dynamism of the West, there are references to languages, the search for identity, culture, the natural landscape vis-à-vis the skyscrapers, life in cabarets; and reflections on goodness and divine grace, on the profane and the religious, and on love sung in its various dimensions.

Rewinding a little, Philomena and Gilbert Lawrence evoke the figure of Luís Vaz de Camões, who wrote a large part of The Lusiads in Goa, and they draw parallels with the life of the eminent Winston Spencer Churchill: both were soldiers of two colonial powers in Asia.

This inter-civilisational dialogue, which began five centuries ago, is still on. For example, the Orient Foundation engages in a wide range of activities, listed here by Paulo Gomes, their delegate in Goa, the oriental Lisboa.

On the other hand, LisGoa, a meeting of business leaders from Goa, is due to be held in the Portuguese capital this month, as highlighted in the special supplement to this edition.

The historical and cultural overview of Goa does not end there. The short story in Konkani, set in the remote taluka of Satari, transports us to a Goa of yesteryear, one might say, pre-Portuguese, as the people’s customs there are very different from those in the Christianised parts of the land. Prakash Parienkar’s ‘The Bitter-Fruit Tree’, transliterated from Konkani in the Devanagari to the Roman script and translated into Portuguese by associate editor Óscar de Noronha, also carries a link to the respective film.

To conclude our presentation of this edition, we draw our readers’ attention to the art section. Girish Gujar and Govit Morajkar, in watercolour and painting, respectively, put the spotlight on two locales in Goa; cartoonist Alexyz critiques issues of contemporary Goa, while Clarice Vaz and Edgar João present Goa as the eternal idyll.

And we cannot resist pointing out that our cover features the Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, Panjim’s most famous landmark; and our back cover has the link to Global Goan, our partner magazine, a must-read for every Goa-phile.