Goencheo Mhonn'neo - V | Adágios Goeses - V

Segue uma quinta lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

Concani | Tradução literal | * Tradução livre

Jiuak suk, pottak duk. | Jivak sukh, pottak dukh.

Para a vida, quietação.

Para a barriga, inanição.

* Quem preguiça e não trabalha,

não ganha p’ra a vitualha.

Fonddachy maty fonddak. | Fonddachi mati fonddak.

A terra de uma cova

não chega para mais,

senão à mesma cova.

* Querer alguém aumentar

os bens ou a fruição,

além da capacidade,

é gastar o esforço em vão.

Borém zalyar noureá-ôclêchém, vaitt zalyar, raibareachém. | Borem zalear novrea-voklechem, vaitt zalear, raibareachem.

Se o consórcio for feliz,

deve-se o êxito fagueiro

aos noivos; sendo o contrário,

a culpa é do medianeiro.

Sambhar cabar zalyar, sacaçó vás vhossó na. | Sambar kabar zalear, sakacho vas voch’na.

Embora esteja esvasiado

o saco de condimentos,

ele há-de exalar o cheiro

de temperos e pimentos.

* Um homem embora esteja

hoje pobre, desditoso,

não perde o aprumo que teve

quando rico ou venturoso.

Vaitt chintit tém yetá ghârá, vhossó na xezará. | Vaitt chintit tem ieta ghora, vochona xez’ra.

Quem quer mal a outrem, ele próprio o alcança,

E não sofre nunca a vizinhança.

* O mal que se quere à gente,

sofre-o o próprio malquerente.

------

[1] Cf. quarta lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 24, setembro-outubro de 2023, pp. 45-46

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

(Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, No. 25, nov-dez 2023, pp. __)

With Joy and Anticipation

Several themes emerge from the Readings of the thirty-second and third last Sunday of the liturgical year: commitment, faithfulness, perseverance, readiness. Since they are all hallmarks of the wise, Wisdom may well be considered the overriding idea.

The First Reading (Wis 6: 12-16) is about divine wisdom. The anonymous author of the deuterocanonical Book of the same name effectively resolves the question of the happiness of the just and the misery of the unjust. Placed as he was in an ambience that prized a materialistic lifestyle, he counters it with a rational basis for a life of faith.

The said author was possibly a Jew based in Alexandria, an Egyptian city that was in the grip of worldly-wise Hellenism. To the Greeks, wisdom was only a means to divine knowledge and contemplation, whereas to our author wisdom was indeed a way of life. He goes on to identify wisdom with the Spirit of God. This is one of the many aspects of our religion that makes it hugely different from the idolatrous ones.

Wisdom is thus a form of divine revelation; it is God acting in the history of the world created by His wisdom. Wisdom has prefigured the love of God and culminated in Jesus Christ, who is therefore called the “Wisdom of God” (cf. 1 Cor 1: 24, 30). It is this Wisdom Incarnate who exhorts us in the Parable of the Ten Virgins: “Watch, therefore, for you know neither the day nor the hour.”

These words wrap up today’s Matthew-exclusive Gospel story (Mt 25: 1-13) of a sundown wedding ceremony. Traditionally, a bridegroom, his family and friends would walk to the bride’s home for some rites. Thereafter, the bride would walk back with them, in a nuptial procession wending through the streets, to the groom’s home. The attendees carried their own torches, and on arrival, bridesmaids welcomed and assisted the bride.

Interestingly, the parable makes no mention of the bride: maybe because the story begins with the groom’s return journey. Besides, the focus is not on the bride but on the preparedness of the bridesmaids. And at what time the bridal party would arrive at the groom’s house was anybody’s guess; so, it was necessary for the bridesmaids to be in readiness. Sadly, five of them were not; the five haves refused to share, so the have-nots scurried for oil at the last minute. They were locked out and disowned by the groom.

When, where and why did Jesus tell this parable? It is a continuation of a dialogue Jesus was engaged in with his disciples (cf. Mt 24) regarding the end times. He wanted them to know that the ten (number of completion) virgins (all Christians, and symbolising purity) who have the oil (grace) when the groom (Saviour) comes again will be invited to the wedding feast (Kingdom of Heaven). Of course, Jesus is the Bridegroom, and His Bride, the Church (a variation of God as Husband of Israel, in the Old Testament).

As for us in real time, what should we find ourselves doing as and when the world ends? Nothing special; we should be going about our daily life normally. And what about those who have gone before us? In the Second Reading (1 Thes 13-18), St Paul states that we have no reason “to grieve as others do who have no hope.” To show that our ancestors have not died in vain, he says: “The dead in Christ will rise first; then we who are alive, who are left, shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air; and so, we shall always be with the Lord. Therefore, comfort one another with these words.”

However, to be able to comfort one another, we ought to be one in mind and heart! Are all Christians on the same page as regards doctrine? Are the Ten Commandments cherished and practised? Do we think about Heaven, the angels and the saints as a living reality? Do we believe that we ought to know God, love and serve Him? Can we say with the Psalmist, “For you my soul is thirsting, O God, my God”? Are sin and grace for real, or inanities?

As we approach the end of yet another liturgical cycle, the Readings of the last three Sundays (12, 19 and 26 November) veer towards the nature of God’s kingdom in the end time, in Matthew 25: the parable of ten virgins (Mt 1-13), the parable of talents (Mt 14-30), and the parable of the last judgment (Mt 31-46), respectively. With this excellent runup to Advent, let us wait with joy and anticipation for the Lord’s coming.

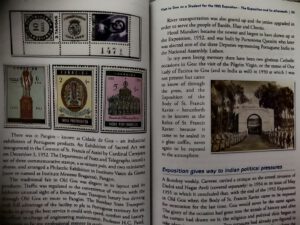

Paean to the Portuguese

THE PORTUGUESE PRESENCE IN INDIA, by João A. de Menezes. Chennai: Notion Press, 2020. Pp 346. ISBN HB 978-1-64850-628-4. Rs 1610/-

This is not macro-history like Danvers’ or Whiteway’s, but an account of the author’s life spent in the bosom of a third culture moulded by the Portuguese presence. In five autobiographical chapters interspersed with four others on broader historical issues he speaks his mind with a forthrightness not common in our days.

Three main strands stand out: the Goan way of life (“Goanism”), including emigration; the Catholic Church in Portuguese and British India; and Goa’s démarches in post-Independent India. “Goanism”, says the author, is anchored to the 451-year-old Portuguese stint and to the age-old comunidades that since the Vedic times have engendered powerful village loyalties.

The author’s own “loyalties” are evident. Despite the author’s long years in Poona, Aden, Bombay, and travels abroad, his heart beats for Goa. There are tender descriptions of ancient institutions; villages and households; the local church and cross feasts; markets and transport systems. Menezes is proud of icons like the Patriarca das Índias Orientais, the Cathedral See, the capital city Pangim, Radio Goa of yesteryear, the Taleigão harvest festival; and he gratefully remembers Governor-General Paulo Bénard Guedes, other men (priest granduncles Canon Bruno de Menezes and Fr Hipólito de Luna included), and matters that contributed towards shaping Goa (“with the exception of the Governor-General and the Chefe do Gabinete, all the other officials of the civil services were Goans and men of integrity”, p. 45).

“Visit to Goa… for the 1952 Exposition” (of the Relics of St Francis Xavier) portrays Menezes as a young man, not only curious about the history of the former capital of the Portuguese Eastern Empire but also attentive to the political goings-on: the “problematic emergence” of the first Indian Cardinal, Valerian Gracias (and his sojourn at Panjim’s Hotel Imperial); pressures on Portuguese India; redistribution of Padroado territory in British India, and so on.

That visit hooked Menezes to his homeland. In “A Tryst with Goa”, he appreciates the cordiality from family and friends, set in a social ambience in which house doors “could remain open with no fear of intrusion” (p. 246). But “the happiest place on earth” (p. 274) was not destined to remain the same for long. The first satyagraha, which involved 100 (out of 100,000) Bombay Goans, in 1954, and none in the following year, demanding ‘liberation’ at the Goa border (p. 264); the severance of diplomatic ties between the Indian Union and Portugal; the Economic Blockade and terrorist threats, which made travel by land a nightmare, and the like, seem to account for the book’s subtitle, “Latter-day thorns amidst tranquillities”. Menezes participated in a first-of-its-kind pilgrimage to Old Goa, praying for peace, in 1956.

Menezes records Goa’s coming of age amidst those “thorns”, thanks to the induction of Transportes Aéreos da Índia Portuguesa (TAIP, whose airhostesses wore saris); upgradation of travel by land, sea, rail and air; optimising of farmland and other resources; importation of cars (Opel and Mercedes Benz as taxis, and the concept of shared taxis, p. 248) and other products; and boost to mining, with Chowgule & Co. as a concessionaire operating an iron loading facility while the rest of the port was managed by the British company that ran West of India Guaranteed Portuguese Railway (WIPR; p. 259).

In two chapters – “My Return to India from Goa” and “Travel between India and Portuguese India” – Menezes dwells on the run-up to the events of December 1961, viz. strategies to dismantle the Portuguese presence; the Goa Office at the Bombay Secretariat, among others. While the Brazilian Embassy’s service to Goans applying for Portuguese passports comes in for special praise here, the subject is dealt with extensively in “Brazil, Caretaker of Portugal’s Interests in the Indian Union – September 1, 1955 to December 31, 1974”. On the latter date, Portugal opened its Embassy in New Delhi.

Three chapters on lesser-known subjects – “The Portuguese Padroado or Patronage and the Indian State”; Indo-Portuguese Notes on Sovereignty”; and “The Referendum Rub: The Inflexibility of the Indian State to permit a Referendum” are mini-dissertations indeed. Menezes draws up a concise history of the Padroado (respected by the Peshwas) and of the Holy See-Portugal Concordat of 1940 (with text in English), and the implications for Goa. His unique contribution lies in examining the impact of Indian Independence on the Padroado, for which purpose he painstakingly translated and critiqued the India-Portugal correspondence contained in the four-volume White Paper titled Vinte Anos de Defesa do Estado Português da Índia (1947-1967), an invaluable resource for researchers.

To put together “Indo-Portuguese Notes on Sovereignty”, Menezes falls back on those diplomatic exchanges, declassified ahead of time (“an act without international precedent”) so the ageing Salazar could let the world know that he had defended the Portuguese Settlements in India with integrity (p. 131). Menezes calls the bluff of Goan political parties’ contribution to the fall of Dadrá and Nagar-Aveli (p. 171 ff) and ends the chapter with a note on “the conquest and subjugation of the Portuguese territories in India” (pp 182-3), with the text of the Indo-Portuguese Treaty of 31 December 1974 (p. 183 ff) added. The Appendix comprises a Goan, Bonifácio de Miranda’s address (apropos the Goa Case) at the UN General Assembly in 1969.

Finally, “The Referendum Rub” is the book’s pièce de resistance. Highlighting UN Charter’s principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, Menezes points to Chandernagore as the subcontinent’s only foreign settlement territory where a referendum was held to determine its political future. Although a referendum for Goa had votaries, “no such referendum was admissible or mandatory under the Estado Novo Constitution of Portugal” (p. 214). In Menezes’ opinion, even if it were permitted in Goa, “weighing the nuances, a referendum might have created more problems than it could solve” (p. 215). In hindsight, “Professor Aloysius Soares’ proposal of Portuguese autonomy [according] to a special constitution followed by a transfer to India with that constitution in place was a pragmatic approach to the future of the Portuguese territories…” (p. 219)

The Portuguese Presence in India, by João A. de Menezes, 90, who retired as chief mechanical engineer of Bombay Port Trust, is truly a labour of love, never mind the publisher’s price tag. A storehouse of memories and musings, blessed with period photographs and good get-up, the hardcover book printed on art paper could have done with better editing, bibliography and index. It is nonetheless a precious contribution to contemporary Indo-Portuguese history and a testament to the author’s love for Goa and insights into her soul.

(Published in Revista da Casa de Goa, Series II, No. 25, Nov-Dec 2023, pp 44-46)

Authentic and Zealous

The Temple of Jerusalem is an important reference point. The one built by Solomon was destroyed in 587 B.C. when the Babylonians torched the city and sent the Judean leaders into exile to Babylon. In 539 B.C. Cyrus, king of Persia, absorbed the Babylonian empire and permitted the Jews to rebuild the temple in their land. On reconstructing the temple in c. 515 B.C., the Jews enjoyed an era of peace but soon became apathetic as regards the divine cult.

Hence, in the First Reading (Mal 11, 22 – 12, 2), Prophet Malachi (the last in the traditional list of minor prophets) censures the people and more so the priests, who were leaders and interpreters of the Scriptures. His discourse begins with an accusation and ends with a sentence: “O priests, this command is for you. If you will not listen, if you will not lay it to heart to give glory to my name, says the Lord of Hosts, then I will send the curse upon you.”

No doubt, we could extend this to ourselves, for we all have the priestly vocation; but here Malachi addresses the sacramental priesthood in particular. His words make one stop in one’s tracks; hence, nothing more dare I say except hope and pray that we turn a new leaf.

Whereas Malachi observes that the priests have been teaching wrong doctrine and misguiding the people, in the Gospel (Mt 23: 1-12) Jesus states that the scribes and the Pharisees have been teaching the law but failing to practise it. They who sat on Moses’ seat – as teachers and leaders – had the moral duty to practise the law (“heavy burdens” or duties) that they imposed on their people. Jesus draws a long list of tricky situations involving those erring leaders and ends with a startling principle: “He who is greatest among you shall be your servant; whoever exalts himself will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be exalted.”

Meanwhile, what did Jesus mean by those intriguing words, “father” and “master”? Is there a ban on their use? Jesus only reminds us that none should usurp the authority that belongs to God, our Father, and Himself, our Divine Master.

St Paul in the Second Reading (1 Thes 2: 7-9, 13) states what it takes to be an apostle: self-sacrifice. However, we must realise that we should not exploit the apostle’s gentleness and mercy; on the contrary, the people ought to show authenticity, fairness, reciprocity, sincerity, gratitude.

Our human condition, fragile as it is, does not make life easy, nor does the Word of God easily sink into us and transform us. That is why what happened millennia ago repeats itself. On the other hand, we must not be discouraged but persevere in letting the Word bear fruit in us. Our reference point is no longer the physical Temple of Jerusalem; Jesus teaches us to live as living temples of God, authentic and zealous.

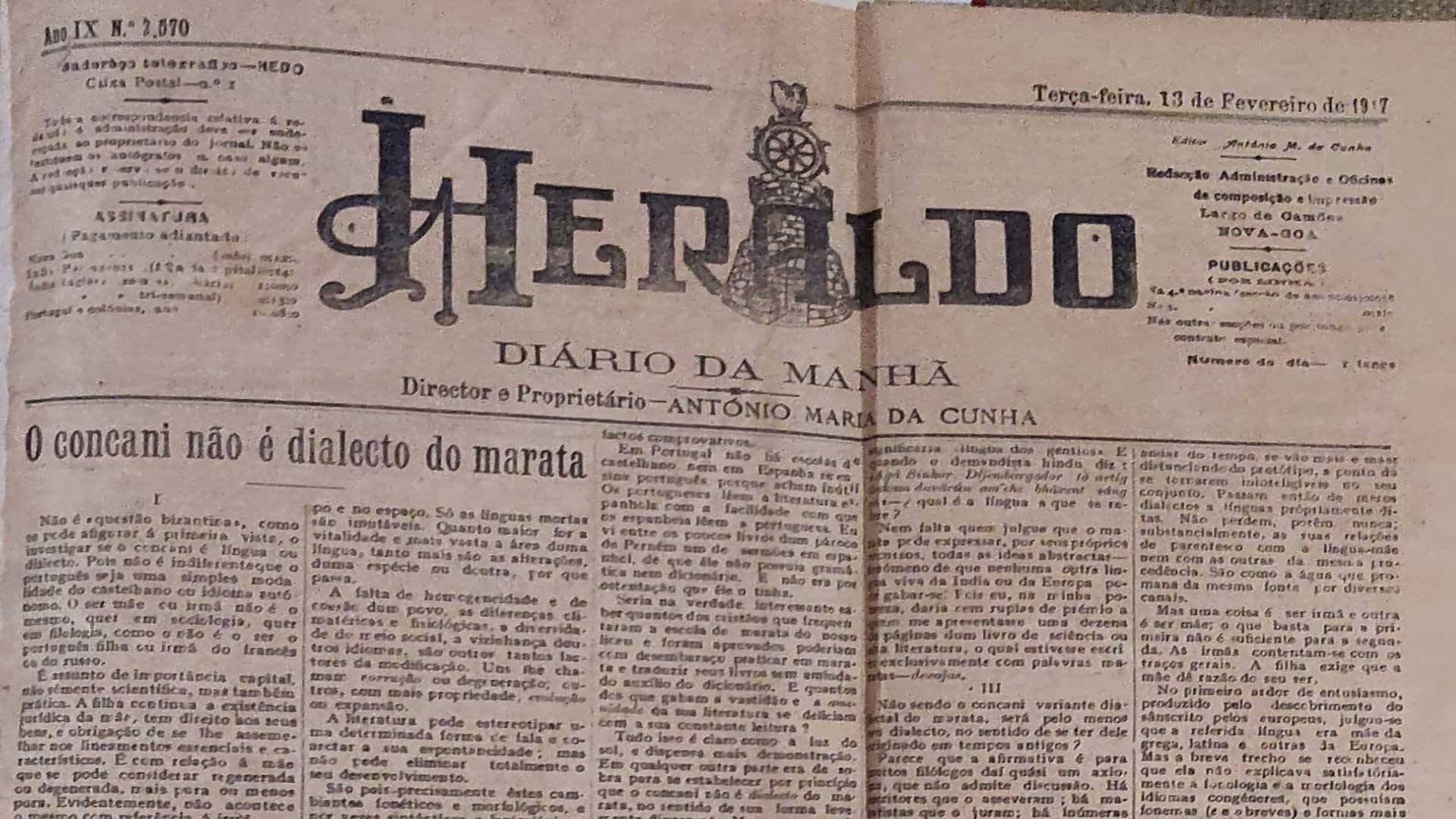

Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi - 2

Part 2 of "O concani não é dialecto do marata", by Mgr. Sebastião Rodolfo Dalgado, in Heraldo, Pangim, Goa, Year IX, No. 2570, 13 February 1917, p. 1)

II

‘Dialect’ is a rather vague and ambiguous word. It is taken in several senses, the two most common being: tenuous grammatical and vocabulary variants of the same language within its area, derivation, usually immediate, from one idiom to another.

Every living language is subject to changes, big or small, in time and in space. Only dead languages are immutable. The greater the vitality and the wider the area of a language, the more the changes of one kind or another that it undergoes.

The lack of homogeneity and cohesion of a people, the climactic and physiological differences, the diversity of the social environment, the proximity of other languages are other factors of modification. Some call that corruption or degeneration, while others more appropriately call it evolution or expansion.

Literature can stereotype a particular form of speech and limit its spontaneity; but it cannot totally prevent its development.

So, it is precisely these phonetic and morphological, and sometimes syntactic and lexicological, variations that constitute dialects in a linguistic space. Their differences in time are known as "phases".

The Portuguese language is regarded as uniform throughout the continental territory. This does not preclude dialectal peculiarities of varying importance in different provinces or districts. Such particularities have been the object of scientific study in modern times, by philologists of the calibre of Dr José Leite de Vasconcelos.

The Konkani language too (so disparaged for this reason) has similar province and class related varieties. Bardez speech is not identical to that of Salcete, nor is the speech of Sawantwadi the same as that of Kanara.

If such a flaw is of major significance, as some philologists there take it to be, other more cultured languages are not exempt from it. Italian has more than twenty dialects, remarkably differentiated; French, at least fifteen, and modern Greek, more than seventy.

But then again, it is evident that such dialects do not destroy the unity of the language. They are like petals of the same flower, like leaves of the same branch. And hence, those who speak different dialects follow each other without any difficulty, when they converse, and they easily understand common literature. The opposite is true of languages and their literatures.

Now, since Cunha Rivara it has been repeated that it is easier for a Portuguese to understand a Castilian than for a Goan to understand a Maratha, and vice-versa. And nonetheless, there are still enlightened spirits in Goa who are not convinced of this palpable truth nor do they wish to do a check for themselves, which is easy to access. They are content – I am not sure if for erudition or for convenience – to rely on the opinions of various authors, not all of them recommended for competence in the matter. Some are foreigners, who have learnt Konkani superficially; others have lived in times when glottology and dialectology made little progress. And they were all were fascinated to note the analogies, but failed to justify the discrepancies.

I can say from experience that I could more easily understand Italian by its likeness to Portuguese than I could colloquial Marathi by its similarity to Konkani. On my first trip to Europe, on an Italian steamer, an Englishman had me as his interpreter to communicate with the cabin boys on board.

And my observation matches. There is no need to pile up supporting facts.

In Portugal there are no schools teaching Castilian nor is Portuguese taught in Spain, as they consider it pointless. The Portuguese read Spanish literature as easily as the Spaniards read Portuguese literature. Among the not many books that a parish priest of Perném had, I saw one of sermons in Spanish, of which he had neither a grammar nor a dictionary. And it was not for show that he had the book.

It would indeed be interesting to know how many of the Christians who attended the Marathi school at our lyceum and graduated would be able to communicate easily in Marathi and translate books without undue aid of a dictionary. And how many of those who praise the vastness and the amenity of its literature are delighted to read it regularly?

All this is clear as daylight, and needs no further demonstration. In any other place this would suffice to establish in principle that Konkani is not a dialect of Marathi, in the sense of its slightly divergent form. But what would be incontestable truth to others, in Goa quite unsurprisingly finds astute opponents, who by hocus-pocus seek to prove that white is black.

It is not without reason that Tavernier wrote in 1676 (Voyages, 1712 edition, III, p. 159): "As for trials, they never come to an end; they are handled by the canarins, natives of the country who practice the professions of solicitors and procurators, and there are no people in the world more cunning and subtle."

Similarly, a very meticulous judge of the Supreme Court told me, not many months ago, that libels from India, besides being longwinded and confused, were not much commended for legal erudition but rather abounded in petty objections and twists to muddle up the truth and obfuscate the law. What the cradle bestows only the tomb takes away.

There are yet those who even grudge Konkani the status of a dialect, calling it simply a "corruption of Marathi". But what is not corrupt, in some sense or other? We ourselves have been corrupt since our first parents’ prevarication. Omnis caro corruperat viam suam, says the Scripture about the antediluvian people. And that we did not get any better after the catastrophe is indicated by events unfolding before our eyes.

If by corruption is meant deviation from the original type, Portuguese, French and Italian are corruptions of colloquial Latin, just as Latin, Greek and Gothic are corruptions of the Proto-Aryan. Gujarati, Hindi and Bengali are corruptions of Sanskrit, or, strictly speaking, of archaic Prakrit languages, just as Sanskrit and Iranian are corruptions of the Indo-European language, which in turn would be a corruption of some other idiom. Corruption of languages is coeval with, if not earlier to, the tower of Babel. However, what to laypersons in the matter appears to be corruption, to those who know is actually evolution.

Of course, Marathi is an exception, for apparently it is in a class apart among the languages of India and the world. A native philologist regarded her as a "beloved daughter of Sanskrit" as though he had witnessed her mother’s caresses; some other decrees her to be Goa’s “national” language, as though this territory were a nation or now under Bhosale rule. Another raises it to the status of a vernacular language – of “our language”, to the Goans! But by what name is Konkani known in the country’s speech? one may ask a child. Certainly not Konkanni bháx, for to the Christians konknnó means “gentile”, and konknni bháx would mean “language of the gentiles”.

And when the Hindu litigant says, ‘Aga Sinhor Dijembargador tó artig âmkam duvârún am’che bhâxent sáng ga’ – which language is he referring to?

Nor is there lack of those who think that Marathi, by its own resources, can express all abstract ideas – a phenomenon that no other living language of India or of Europe can boast of. And I, in my indigence, would give one hundred rupees as a prize to whoever showed me some ten pages of a book of science or of high literature written exclusively using Marathi words – dexajas.

Love: for God’s sake

As we continue reading from the Gospel of St Matthew (22: 34-40), we see how Jesus counters his adversaries. He had just finished silencing the Sadducees on the question of the resurrection of the dead, when he was assailed by the Pharisees. They wanted Him to pronounce on the ‘Great Commandment in the law’. Jesus assigns equal importance to the two commandments known in the Old Testament and focusses on them the entire content of the law. Loving God with our heart, mind and soul is the first and great commandment, He said, and by the second, which is like it, we ought to love our neighbour as ourselves.

But who is our neighbour? From the parable of the Good Samaritan, we learn that our neighbour is essentially a person in need. In our materialistic age, we think of money as the need, but that simply is not the case. Very often, the other yearns for our love, our time, just a little word or a listening ear. It may not even require our physical presence; sometimes a tinkle, a WhatsApp message, a comforting thought from afar, could save the day. We will never know in advance who we are called to serve, when and how. But serve we must; and those that we serve are our neighbour, and service is the expression of our love.

But then again, what is love? Someone has said: “Love is the most beautiful thing to have, hardest thing to earn and most painful thing to lose”; but far from defining, it makes love seem elusive. In 1 Corinthians 13: 4-7, some of love’s attributes make it palpable: “Love is patient; love is kind; love is not envious or boastful or arrogant or rude. It does not insist on its own way; it is not irritable; it keeps no record of wrongs; it does not rejoice in wrongdoing but rejoices in the truth. It bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.”

Palpable but not defined. That is because love is a many-splendored thing, largely misunderstood and therefore clichéd, especially in our times. Several Catholic thinkers have dwelt upon this inexhaustible topic, and more recently, in his book The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis has distinguished between Affection, Friendship, Eros and Charity, showing how one merges into another, and how one can even become another. More importantly, he underlines that the first three – human loves – can be tainted if not accompanied by the sweetening grace of divine love, Charity. And, as St Ignatius put it: “Love is shown more in deeds than in words.”

We understand love more concretely through the First Reading (Ex 22: 21-27) in which God forbids us to wrong a stranger or oppress him; to afflict a widow or orphan; or to torment a poor man. They are personae miserabiles – people in difficult social, economic and juridical situations. Easing their situation constitutes works of mercy that our Catechism speaks of: “charitable actions by which we come to the aid of our neighbour in his spiritual and bodily necessities.” Instructing, advising, consoling, comforting, forgiving and bearing wrongs patiently are spiritual works of mercy; the corporal include giving alms to the poor, feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and imprisoned, and burying the dead. (Cf. CCC, 2447)

Christian civilisation traditionally grew up on those sublime teachings and achieved a healthy balance between body and spirit down the ages. But alas, with the overpowering rise of godless modernism, haven’t some people grown weary of the teachings that had once nourished them? The consequence of such degradation has been staring us in the face. And with the recent opening of the gates of Europe to hordes of people (refugees, asylum seekers, migrants), some of whom are avowedly spiritual enemies of Christian civilisation (or what is left of it), shouldn't it be reexamined whether the physical needs of the neighbours are more crucial than the spiritual wellbeing of the household?

St Paul was extremely concerned about the spiritual health of his people. In the Second Reading (1 Thes 1: 5-10), he is all praise for the example that the Thessalonians have set to the believers in Macedonia and Achaia. The Word of God sounded forth from them like clarion trumpets and their faith went forth everywhere. God was their highest good, from which the good of neighbour flowed. Hence the Apostle is happy to note how they “turned to God from idols, to serve a living and true God, and to wait for His Son from Heaven, whom He raised from the dead, Jesus who delivers us from the wrath to come.”

Would it be wrong to see God’s wrath in terms of environmental disasters and wars? Aren’t we witnessing veiled religious and spiritual wars? Spiritual warfare is a fact of life; we cannot wish it away. So, it would be necessary to reflect on how far enemies of Christianity can be our ‘neighbours’!... Can they be allowed to hack at the very foundations of Christian civilisation… and we foolishly call it ‘love’? We cannot forget our duty to love God above all things, and the neighbour for God’s sake.

Unto God and Caesar

This Sunday’s Gospel text (Mt 22: 15-21) picks up where we left off last Sunday. The wedding feast parable was a subtle attack on the Jewish authorities. Such was their hatred of Our Lord that even two divergent groups did not think twice before they got together to checkmate Jesus: Herodians, a political party at least outwardly friends with the Roman authorities and indifferent to religion; and the Pharisees, puritanical as regards the Jewish law and traditions, and opposed to Roman rule. Devising a ploy from which it seemed impossible for Jesus to escape, they got some young scholars to pose the following question with guileless simplicity: “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not?”

Jesus was faced with a false dilemma, for to condemn the Roman tax would be to incur the vengeance of those pagan rulers; to consider the tax legitimate would anger the Jews, who had always resented the Roman rule. Seeing through the trick, Jesus asked for a coin, pointed to the image and inscription on it, and promptly replied, keeping his tone light and matter-of-fact: “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” This exposed the hypocrisy of the Pharisees, who used Roman currency for trade and commerce, yet grudged the payment of tax; so too the Herodians, who could easily be charged with detracting against the Roman authority.

Jesus thus made it clear that while political masters seek taxes God seeks souls. Or as Fulton Sheen points out, “Once again He was saying that His Kingdom was not of this world; that submission to Him is not inconsistent with submission to secular powers; that political freedom is not the only freedom. To the Pharisees who hated Caesar came the command: ‘Give unto Caesar’; to the Herodians who had forgotten God in their love of Caesar came the basic principle: ‘Give unto God.’”[1]

Does that amount to serving two masters? No. The two masters that we cannot serve at the same time are God and Mammon (pleasures of the world included). These we cannot serve alike because they are things opposed to each other; to serve one we often (have to) forego the other. For instance, when it comes to running a business and amassing wealth we may think that ends justify the means, sacrificing even religious worship on Sundays and holy days. On the other hand, serving a legitimate temporal authority is necessary for the smooth functioning of society; it is a different matter if the authority acts immorally and illicitly, but our basic aim should always be to align earthly administration with divine law.

In the ultimate analysis, everything belongs to God, doesn't it? Hence, in the First Reading (Is 45: 1, 4-6), God makes it clear that He is the Lord and there is no other. He is always in control and exercises dominion even over those who do not acknowledge Him. For instance, God had the Persian king Cyrus put an end to Babylonian rule and free the Jews. ‘Anointed’ were the kings of Israel alone, but since Cyrus as God’s instrument in the liberation of Israel is regarded as anointed, too.

To pay God tribute, we ought to sing His praises and “tell among the nations His glory and His wonders among all the peoples.” That is to say, we have to evangelise. We can do so from wherever we are, whatever be our station in life. We can do so without worrying about what we are going to say, for then the Holy Spirit takes charge and guides us. In fact, we can go forth and preach through our actions rather than our words: we can engage in the apostolate of presence. “Preach the Gospel at all times, and if necessary, use words” is a quote commonly attributed to St Francis of Assisi.

But alas, on World Mission Sunday being observed today, it is imperative for us to check the nature and state of our Missions. Is evangelisation happening in reality, that is to say, are we genuinely proclaiming the Gospel message, or is it only an exercise in social service? This day is marked by a special collection taken up to support "missionary projects", but are these the same pious projects that you and I have in mind? Have a look at the links below, to see whether we are "converting" others or "perverting" ourselves! Hence an appeal was recently made by a Lay Catholic faithful organisation, to the Bishops of India, to stop the menace of theological errors being spread under the pretext of "inculturation": https://youtube.com/shorts/kagBOaVfIj0?feature=share and https://www.saveourfaith.com/

In the Second Reading (1 Thes 1: 1-5), St Paul, on behalf of his missionary companions Silvanus and Timothy, and himself, informs the Thessalonians of how he and his own pray and thank God for their “work of faith[2] and labour of love and steadfastness of hope in our Lord Jesus Christ.” Such graces are divine gifts, which we should always appreciate. Just like the Thessalonians, who were newly formed into a faith community, continued to be challenged by paganism all around them, we Christians in the contemporary world are continually confronted by innumerable temptations and traps from a neo-pagan world. So, the lesson to learn is that what we give unto Caesar should by no means prevent us from giving unto God.

----------

[1] Fulton Sheen, Life of Christ (Bangalore: Asian Trading Corporation, 1984), p. 203

[2] This throws up the controversial topic of faith without works.

The Elect to Eternal Life

The Readings of today provide at least a faint background to the goings-on in West Asia, a region long steeped in violence and terrorism. While the Jews claim that the recent attack on Israel has been the deadliest for them since the German Holocaust, one can’t help but think of the Prince of Peace who once walked that way with a promise of great hope for the human race!

God made many several covenants with the people of Israel. In the First Reading (Is 25: 6-10) we note His promises of freedom and celebration on Zion, the mount on which the city of David was built. In its Temple God has promised to unite the peoples of the world. There they will live in harmony, putting behind them pride, hatred, injustice and war. With joy and life replacing mourning and death, the people will sing, “This is the Lord; we have waited for Him; let us be glad and rejoice in His salvation.”

The Lord is none other than Christ our Saviour. David’s Psalm 23, too, famously reminds us that in good times and in bad, in sickness and in health, the Lord is our Good Shepherd. Those who trust in Him shall not want but enjoy green pastures, restful waters, sufficient repose and a joyful spirit. For He is the God of wisdom, strength and kindness; who guides us, walks by our side, comforts, feeds and anoints us. The Psalm spoke warmly to the heart of pastoral Israel.

Jesus’ parable in today’s Gospel text (Mt 22: 1-14) brings the images of the Old Testament closer to us by comparing the Kingdom of Heaven to a sumptuous wedding banquet. The first invitees (representing the Jews, who were the first to hear God’s Word) failed to honour the king’s (God’s) invitation: they not only went about their own petty tasks, but even killed the king’s messengers! Much like the owner of the vineyard, in last Sunday’s parable, the king sent his troops to destroy the murderers and burn their city. Finally, he extended his invitation to the rest of the world (thus announcing the universality of the Kingdom of God), and the wedding hall (His Church) was full.

But then again, who is the “man who had no wedding garment”? In those days, all guests were supplied with a robe to wear at the banquet; but here was a stranger, probably a crasher, who either had no robe or had failed to wear one. Not to be taken for a poor man but a guest flouting the norms, he is, quite expectedly, shown the door. In like manner, why won’t those who disregard the Commandments be bound hand and foot and cast into the “outer darkness” (hell), where men “weep and gnash their teeth”?

Jesus makes it clear that the divine invitation is gratis but also exacting. It is the wearing of the garment of Christ in a worthy manner that will entitle us to the heavenly banquet. Even though He has invited all into His tent, only those who have fulfilled the stipulated conditions will be chosen to dine with Him.[1] It is ironical that even at the Last Supper this truth had not dawned on the Apostles!

For that matter, did the Jews remember the parable when Jerusalem and the temple were reduced to rubble in 70 A.D.? And will they now turn a new leaf? God, who is slow to anger and abounding in love, is never discouraged. He continues to make overtures of friendship. Hence, quite significantly, the Jews, themselves a persecuted and dispersed lot, are gathering back in their land after two millennia in exile. This is not to absolve their governments from their continued violence, which is the handiwork of evil men in the Holy Land. Be that as it may, will the Jews finally seize the day and turn to the True God?

Only a profound change of heart can bring about a transformation in the world at large. St Paul refers to the necessary dispositions, in the Second Reading (Phil 4: 12-14, 19-20). He who had received substantial material help from the Philippians was not overly concerned about how he should be living. The message he wishes to highlight is that God is the great Provider of our every need, according to His riches, in marvellous ways, in His Son Jesus. So, when we are with the Good Shepherd, we have nothing to fear; when the Good Lord is with us, none can be against us.

Let us therefore never decline a good invitation; and if it be a divine call, let us accept it wholeheartedly and be steadfast, so as to be counted among the elect to eternal life.

------

[1] This parable has a parallel only in Luke 14: 16-24.

Goencheo Mhonn'neo - IV | Adágios Goeses - IV

Segue uma quarta lista de adágios,[1] extraídos do livro Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, obra bilíngue (concani-português), de Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda (1872-1935)[2].

Tradução literal | Tradução livre

Fôttquiryachém nãy sot, ani pav’sachém nãy vot. | Fottkireachem nhoi sot, ani pavsachem nhoi vot.

Não se deve fiar num homem mentiroso, como na luz do sol, no tempo invernoso.

Donn hoddyen’ar pãyem dovorlyar doriyant poddta. | Don hoddeamni paim dovorlear doriant poddta.

Aquele que firmar os pés sobre dois barcos, mergulha-se no mar.

Quem faz dois negócios opostos

ou claramente incompatíveis,

expõe-se a desastre e desgostos.

Natçunk nenom teká, angonn vankddém. | Nachunk nennom taka angonn vankddem.

A quem não sabe dançar, co’arte e geito,

o terreiro é que está torto, imperfeito.

Sempre um ignorante,

que tem petulância,

lança no outro as culpas

da sua ignorância.

Bhirant assá, punn lâz nam. | Bhirant asa, punn loz na.

Tem medo (que seja punido)

mas não tem vergonha (o atrevido).

Cat mely zalyar, zat melâ na. | Kat mell’li zalear, zat mellna.

Por se tornar a tez escura,

a casta não se desnatura.

A procedência de alguém

não se aquilata p’la cor

da tez que a pessoa tem.

------------------------

[1] Cf. terceira lista, Revista da Casa de Goa, Série II, No. 21, março-abril 2023, pp. 59-62

[2] Roque Bernardo Barreto Miranda, Enfiada de Anexins Goeses, dos mais correntes (Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1931), com acrescentamento dos adágios na grafia moderna, pelo nosso editor associado Óscar de Noronha.

Publicado na Revista da Casa de Goa, Serie II, Set-Out 2023, No. 24, pp. 45-46

Labouring in the Vineyard

On a third consecutive Sunday[1] we are captivated by the image of the Vineyard. In fact, since times immemorial, prophet after prophet has made use of this charming feature of Israel’s landscape to make a valid point. With grapes as an agricultural item playing an important role in the economy, society, and even in the faith traditions of the Jews, and later of the Christians too, it is no wonder that the Holy Bible abounds in parables relating to the Vineyard.

Bible commentators say that one of the best-known uses of the vineyard symbol in the Old Testament occurs in Isaiah, of which today’s First Reading (Is 5: 1-7) provides the core: “The vineyard of the Lord of hosts is the house of Israel.” Here, Isaiah recalls how the owner (who represents God) tenderly cared for his vineyard (His people Israel). And yet, how did the vineyard respond? By producing wild grapes (unruly behaviour or sin). It is quite natural that the owner should destroy such worthless plantations (quite clearly, symbolic of retribution for sinful human behaviour).

Historically speaking, the retribution that Isaiah hinted at was the Assyrian military attack that the southern kingdom, Judah, was anticipating, just as the northern kingdom of Israel had experienced earlier. The Prophet’s argument was that God had punished Israel for their unfaithfulness; and Judah could well avert its share of problems by changing their ways and strictly following God’s law. Yet, Isaiah is not all that hopeful, for God had once looked for justice but witnessed bloodshed; righteousness, and alas, beheld a cry.

Jesus’ parable in the Gospel text (Mt 21: 33-43) uses the vineyard symbolism with a more palpable human element: it replaces wild grapes with wild tenants. Since they have beaten, stoned, abused and killed the owner’s servants, and even his son, all of whom he had dispatched, in quick succession, he “put[s] those wretches to a miserable death, and let[s] out the vineyard to other tenants who will give him the fruits in their seasons.”

How loaded with meaning! While the owner here still symbolises God, and the vineyard His people Israel, the ominous part is that the tenants represent officialdom and religious authorities to whom souls have been entrusted. Have they been reliable stewards of God’s property? The son there is the Son of God, Jesus Christ our Lord. Did Israel respect Him? No; they took Him who was the heir, cast him out of the vineyard and killed him. And what about us today? We still do the same every time we reject Him and through other sinful acts.

How loaded with meaning! While the owner here still symbolises God, and the vineyard His people Israel, the ominous part is that the tenants represent officialdom and religious authorities to whom souls have been entrusted. Have they been reliable stewards of God’s property? The son there is the Son of God, Jesus Christ our Lord. Did Israel respect Him? No; they took Him who was the heir, cast him out of the vineyard and killed him. And what about us today? We still do the same every time we reject Him and through other sinful acts.

Alas, while many have embraced the Faith, not all have stayed faithful. Thus, after Israel rejected Jesus, the Faith moved to the West, where it flourished for centuries, fulfilling the words of our Lord and Master: “The kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a nation producing the fruits of it.” But, eventually, that part of the world too, after reaping the fruits of Christian Civilisation, was ungrateful and failed to cling to the old rugged Cross. With ever-growing affluence and misplaced confidence, the West slowly but steadily dropped their guards, and finally apostatised. And most worrisome is the fact, as Pope Paul VI put it, way back in 1972, that “the smoke of Satan has entered the Church of God.”

Jesus is that rejected stone whom God has destined to be the cornerstone of salvation: “The very stone which the builders rejected has become the cornerstone; this was the Lord’s doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes.” Presently, the greatest hope comes from the Asian and African continents. For instance, in a nascent sovereign country like East Timor, the people have chosen the Catholic Faith, and this has gone from strength to strength (20% - 98%). For their part, several African nations have been among the staunchest supporters of Catholic morality and discipline, as seen from their brave rejection of homosexuality, transgenderism, divorce, ordination of women, and so on. Their Cardinals assert themselves at the Vatican and their people at home are among those who show God’s Vineyard as an image of hope.

Finally, even while social, political, economic and environmental issues on our fragile planet are beginning to assume apocalyptic proportions, we must be people of hope – not grapes of wrath but of sweetness. Elsewhere in the Bible, Jesus says, “I am the Vine, you are the branches” (Jn 15: 5). In the Apostolic Age there was a question on whether values of the Greco-Roman pagan civilisation could be absorbed. In response, St Paul appealed to the Philippians to exercise discernment about what is true, honourable, just, pure, lovely, gracious, excellent and worthy of praise. One more reason to take seriously the Apostle of the Gentiles’ exhortation in the Second Reading (Phil 4: 6-9): “Have no anxiety about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which passes all understanding, will keep your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.”

------------------------

[1] As an exception this year, the Readings of the twenty-sixth Sunday pertained to the Feast of St Thérèse of the Child Jesus.