Is the deletion of Passiontide from the liturgical calendar a sign that our Lenten spirit has slackened? Do we therefore need to step up our acts and symbols to drive its point home?

The fifth Sunday of Lent was traditionally called ‘Passion Sunday’, marking the beginning of ‘Passiontide’. During this two-week long period, which comprised the ‘first’ and ‘second’ Passion Sundays, the Church would intensify her preparations for the Holy Triduum and Easter celebrations. However, with the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council, ‘Passion Sunday’ was practically done away with; the name is, at best, second to the official designation ‘Palm Sunday’, which marks the beginning of Holy Week.

Thus, not only Passiontide as a distinct liturgical season within Lent but, eventually, even the term ‘Passion Sunday’ came to be abolished. This was done ostensibly because the notion of the Passion, that is, the suffering and death of Jesus Christ, is already contained within the forty days of Lent. It was also thought to be potentially confusing and distracting to have a season within a season.

Critics of the abolition, however, point out that such an approach is not consistent across the 1970 Roman Missal, for instance, at Advent.[1] They also opine that ‘the overly-rationalist logic of the [post-Vatican liturgical] reform came up against the traditional piety and practice of the Church.’[2] Even so, from Monday of the fifth week of Lent onward, the Church tries to preserve the liturgical and devotional intensity of the old Passiontide through liturgy, hymns and rubrics, but refrains from explicitly stating so.

Critics of the abolition, however, point out that such an approach is not consistent across the 1970 Roman Missal, for instance, at Advent.[1] They also opine that ‘the overly-rationalist logic of the [post-Vatican liturgical] reform came up against the traditional piety and practice of the Church.’[2] Even so, from Monday of the fifth week of Lent onward, the Church tries to preserve the liturgical and devotional intensity of the old Passiontide through liturgy, hymns and rubrics, but refrains from explicitly stating so.

This goes to prove that there is an unstated need for intensification of the Lenten fervour over a period longer than just a week. Earlier, the most obvious example of a more sombre mood was the veiling of statues and images, which remains an optional practice in the current Roman Missal. Another was the feast of the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary on the first Friday of the Passiontide, now transferred to September. Various other practices occurred during the final two weeks of Lent, such as Stations of the Cross and the Tenebrae services. In short, Passiontide was meant to be a special penitential period where the faithful focussed more intensely on Jesus’ bitter passion and fostered in us sorrow for our sins.[3]

Meanwhile, the traditional Roman Missal (as well as several other Christian denominations) observes this special time in the Church’s calendar quite austerely. It is one of the many treasures of the traditional rite that can be regarded as a feast for the soul; their solemnity, beauty, and spiritual benefits are undeniable. As part of the ongoing reassessment of the liturgical reforms, Pope Benedict XVI, himself an architect of Vatican Council II, states:

‘In the history of the liturgy there is growth and progress, but no rupture. What earlier generations held as sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful. It behoves all of us to preserve the riches which have developed in the Church’s faith and prayer, and to give them their proper place.’[4]

In times gone by, civil law would unite with Church law to ensure that the faithful understood and gave due importance to Lent. Today, the secular world unites with watered-down ecclesial practices, wittingly or unwittingly making sure that only a few consciously live through Lent. Our bustling lifestyles and the dazzling city lights conspire to dish out utterly Godless experiences that leave us morally and spiritually crushed – ‘snuffed out like a wick’.

But let us not be disheartened. Let us devise a Lenten routine that will advance our individual and collective spiritual growth through spiritual reading, appropriate music, meditation, prayer, confession, the Holy Eucharist, fasting and almsgiving. Let not the Passiontide ebb within us. And then, in a couple of weeks, when we look back on how we had let the austerity of Lent wage war on our sensual appetites, we will surely feel a regeneration of body and soul, and what is more, witness the birth of an authentic joy with which to welcome the feast of Easter.

[1] Special Mass propers were assigned to the last few days of Advent (17th-24th December), to give extra emphasis to the end of this season and assist the faithful to prepare for the celebration of the Lord’s first coming. Clearly, the Council did not think this extra emphasis affected the unity of Advent, or could have been confusing for the faithful. Why, then, did they think that keeping Passiontide would affect the unity of Lent or be confusing? Cf. https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2021/03/the-fate-of-passiontide-in-post-vatican.html Accessed 2 April 2022

[2] https://rorate-caeli.blogspot.com/2021/03/the-fate-of-passiontide-in-post-vatican.html Accessed 2 April 2022

[3] https://aleteia.org/2017/03/30/what-is-passiontide/

[4] Benedict XVI, Letter on the occasion of the publication of the Apostolic Letter “motu proprio data” Summorum Pontificum, on the use of the Roman liturgy prior to the Reform of 1970. 7th July 2007 (http://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/letters/2007/documents/hf_ben-xvi_let_20070707_lettera-vescovi.html) Accessed 2 April 2022

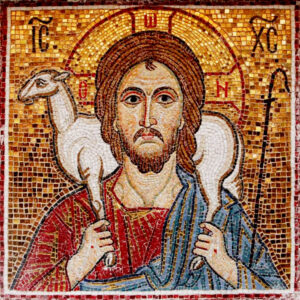

[Banner: Dreamstime.com]

So true Oscar. Everything is watered down and it looks like it is starts right from the top. Here is a beautiful playlist, which is a favorite of mine by the Crusaders of Jesus and Mary, titled Recognizing the Signs and Preparing Yourself

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoLdNFhYv8c&list=PLdH12ZQy2b3M4VW1r_nXyzOCXAZjraOq6

Hi Noel, thanks for your comments and for the link. The link didn’t take me to your playlist but to a talk by Edmund Antao, which I did profit from. So, thanks anyway; but please don’t forget to send me your playlist.

Excellent research into pre vatican 2 practices in the Church calendar, the reverence we felt with those beautiful services and how we are given a truncated version and bereft of many sombre and solemn prayer activities. It feels that with the modernization of the Church where man has little time in hand to endure long services we have compromised a lot. Perhaps we need to take a leaf out of the Orthodox Church practices.

In Immortale Dei, Pope Leo XIII says, ‘There was once a time when States were governed by the philosophy of the Gospel.’ Indeed, the world was inspired by the Church. Is it the other way round today? Alas, are we shirking our responsibilities?

Thanks, Oscar, for this enlightening article. Vatican Two’s liberalism has sadly resulted in diluting many Lenten practices. Ultimately, the goal is to draw souls to Jesus. If the relaxation of traditional practices has served this purpose then it is the work of the Holy Spirit.

But has it, Maria Ana? Only the Holy Spirit knows! On the other hand, why do see more and more of godlessness around us? That’s worrisome. But then, we know God is in control. Let’s trust in the Lord.